When a central bank seeks to stimulate a moribund economy, it employs various mechanisms to lower interest rates. Lower rates mean cheaper loans and less interest on savings deposits. That encourages consumers to spend and businesses to invest.

This type of stimulus is particularly effective for durable goods like cars, appliances, and homes—big-ticket items that are sensitive to interest rates. Interest rate cuts are therefore a crucial part of the monetary transmission mechanism—the means by which central bank policies affect economic activity. In short, it’s how the Fed achieves its dual mandate: maximum employment and stable prices.

But new research from the Minneapolis Fed suggests that this policy tool may have unintended consequences. Rate cuts do indeed stimulate durable goods purchases, the research finds, but by convincing consumers and businesses to buy now rather than later. This leaves fewer purchases in the future: A family that buys a home in May is unlikely to buy another in July.

“While monetary policy is able to stimulate economic activity in the short run, it comes at the cost of weaker activity in the medium run,” write Alisdair McKay of the Minneapolis Fed and Johannes Wieland of UC, San Diego.

Intertemporal shifting of demand is the term the economists use to describe this phenomenon, and their paper explores its implications for central bank policy, trends in interest rates, and the relationship between the two.

“Stimulus today,” they write, “leads to weaker demand in the future by shifting the timing of durable expenditure forward.” This suggests that to stimulate the economy later, a central bank will need to continue to keep interest rates low. Intertemporal shifting thus generates persistent downward pressure on rates and, in an era of already low interest rates, nudging rates down becomes increasingly difficult.

By clarifying the importance of intertemporal shifting, their work has strong implications for monetary policy. The research also addresses two related theoretical questions: Why have interest rates been so low over the past decade? And is the natural rate of interest—the rate consistent with stable prices and full employment—independent of monetary policy?

On the cusp

To understand the impact and implications of intertemporal shifts, McKay and Wieland use a heterogeneous agent model—a model that allows for people to vary in their economic characteristics. In this case, the key difference is where people stand in relation to needing a new durable good. Some households and businesses are on the verge of a big purchase; others aren’t planning any major buys for several quarters or longer—depending on budgets, depreciation of existing durables, and life circumstances. (Because these items depreciate slowly and are replaced infrequently, they’re referred to as “lumpy” purchases or investments.)

In their model, interest rate cuts shift purchases by households and businesses to an earlier date. That boosts aggregate spending, as policymakers intend. But it leaves fewer buyers ready to pull the trigger next month, or the month after. Today’s demand thus undermines tomorrow’s. “As a result, aggregate demand is weaker in periods following the stimulus,” they write.

Testing the model

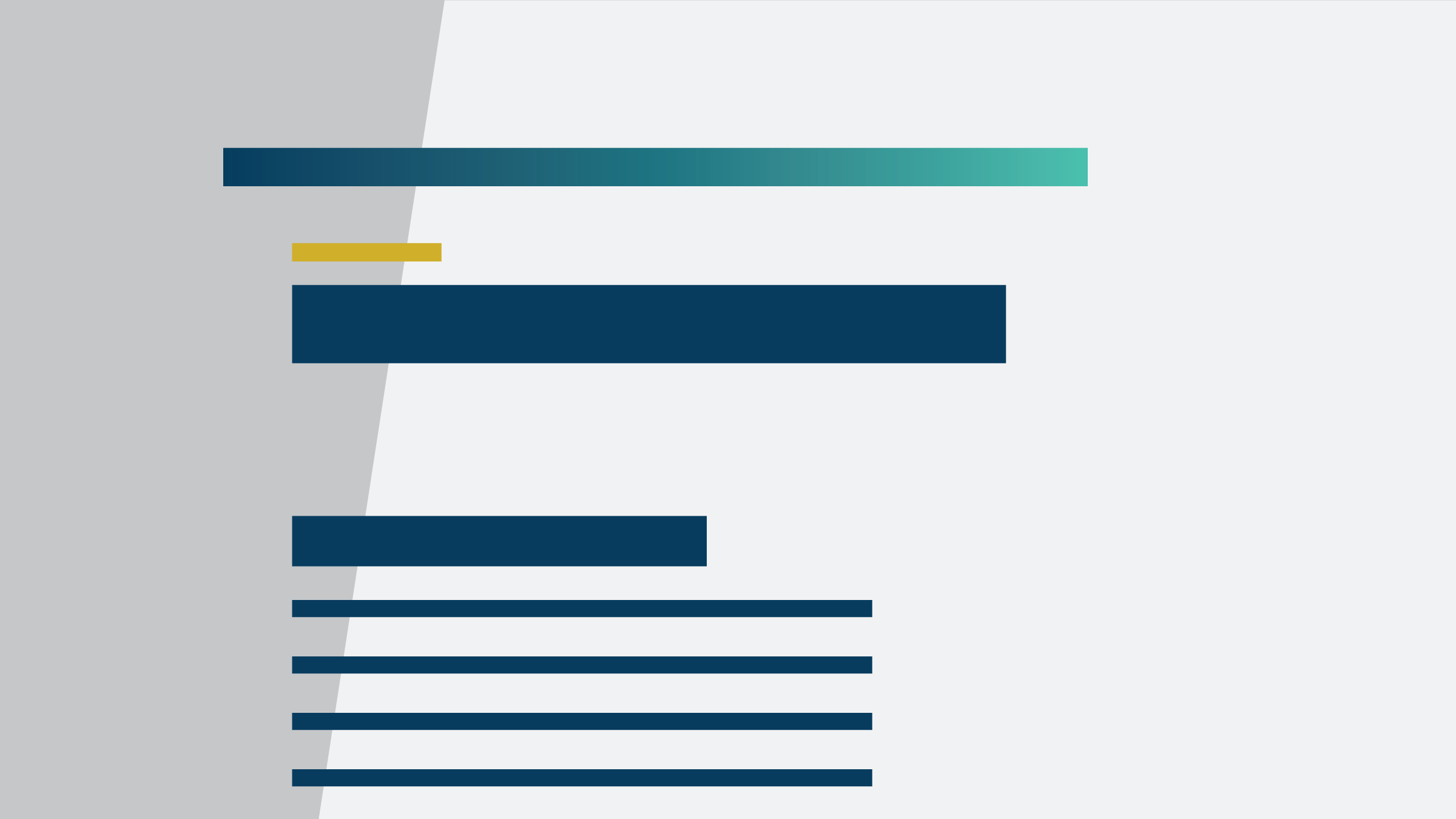

It’s a cogent theory, but does it conform to reality? To gauge whether intertemporal shifting of durables demand does indeed affect monetary transmission, the economists use their model to forecast inflation-adjusted interest rates after the Great Recession. (See the accompanying figure.) The model forecast matches U.S. data well, with rates staying extremely low until late in 2015, when rates actually began to rise. Even then, rates rose slowly, in model and reality.

Durable purchases are key to achieving the accurate forecast. A forecast of interest rate cuts on expenditure for nondurables—goods like food, entertainment, and clothing—diverges widely from the data. Interest rates shoot up in late 2012 in the model, well before they actually did.

Two features are central to the success of the durable goods model: match quality and operating costs. Without them, the model overshoots reality, indicating that interest rate cuts stimulate more consumption than they actually do.

By match quality, McKay and Wieland mean instances where households buy new products not because of rate changes, but because their current product—a home, a car, a couch—no longer suits a family’s circumstances. Perhaps a new job requires moving and buying a different home, or a child is born, so the family needs a bigger car. These “match quality shocks” take potential spenders off the market in the near future and thereby dampen responses to interest rate cuts.

Operating costs are the outlays by owners—gas for the car, paint for the house. These too reduce the rate sensitivity of durable demand because while they’re significant budget lines, they’re not much affected by interest rates.

Persistently low

Interest rates have been declining for 40 years. The 10-year Treasury note, for instance, yielded over 15 percent in 1981. It now pays well under 2 percent. There are many theories for the decline; each is likely part of the puzzle. Since the financial crisis, people are looking for safe assets, regardless of yield. Demographic changes favor saving rather than spending. New industries are less capital-intensive than the old and perhaps less competitive, so investment demand is low. China’s economic growth and high savings rate means that capital markets are flush and so pay less interest. Inequality has soared, and the rich save much of their income. And economic growth is lower than in the 1960s and ’70s so, again, capital demand is lower.

To these and other theories, McKay and Wieland add another. Prolonged periods of easy monetary policy after the financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic have steadily shifted durables demand forward and created persistent downward pressure on rates. They isolate the contribution of intertemporal shifting to the downward path of interest rates and find that it’s “quantitatively important” to explaining the large drop and, especially, the slow rise to equilibrium levels after the Great Recession.

This factor was a substantial force over the past decade, say the economists, and fully compatible with other nonmonetary theories on rate decline since the 1980s.

Stimulus lowers the natural rate

Monetary theorists generally see the “natural rate of interest,” the economy’s fundamental interest rate, as being independent of monetary policy. The natural rate, economists believe, is determined by underlying economic forces such as productivity—an economy’s ability to convert its resources into useful goods and services.

McKay and Wieland’s work suggests that this independence is a fiction. Since monetary policy induces intertemporal demand shifting, it must keep interest rates low to sustain future demand. “Monetary policy stimulus has a side effect of reducing the real natural rate of interest (r*) in subsequent periods.” In the present day, this has brought rates toward what economists refer to as the “effective lower bound”—when interest rates approach zero and can fall no further. Thus, the repeated use of interest rate cuts may have reduced future policy ammunition.

Less room to maneuver

While it seems, at first glance, a rather simple notion, intertemporal shifting provides a powerful explanation for the course of interest rates since the Great Recession, offers a novel answer to a long-standing puzzle about interest rate declines, and upends conventional wisdom about interest rate independence. Most significantly, it suggests that central bankers may find themselves constrained by policy steps they’ve taken in the past.