The U.S. tax code is notoriously complex, as anyone who has ever filed a federal tax return will confirm. Its rules, reforms, and repeals run thousands of pages, a tome that keeps the $10 billion tax preparation services industry running strong.

While there are many reasons for this complexity, one of them is the way the tax code and Social Security program treat married couples, economists Margherita Borella, Mariacristina De Nardi, and Fang Yang explain in “Are Marriage-Related Taxes and Social Security Benefits Holding Back Female Labor Supply?” a working paper from the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute.

In many countries, marital status does not impact how an individual’s income is taxed because all taxpayers file as individuals. But in the United States, most couples file a joint tax return and pay taxes on their combined income.1 The federal government implemented this system in 1948 to eliminate differences in how married couples were treated under state tax laws. At that time, only a quarter of married women worked outside the home.

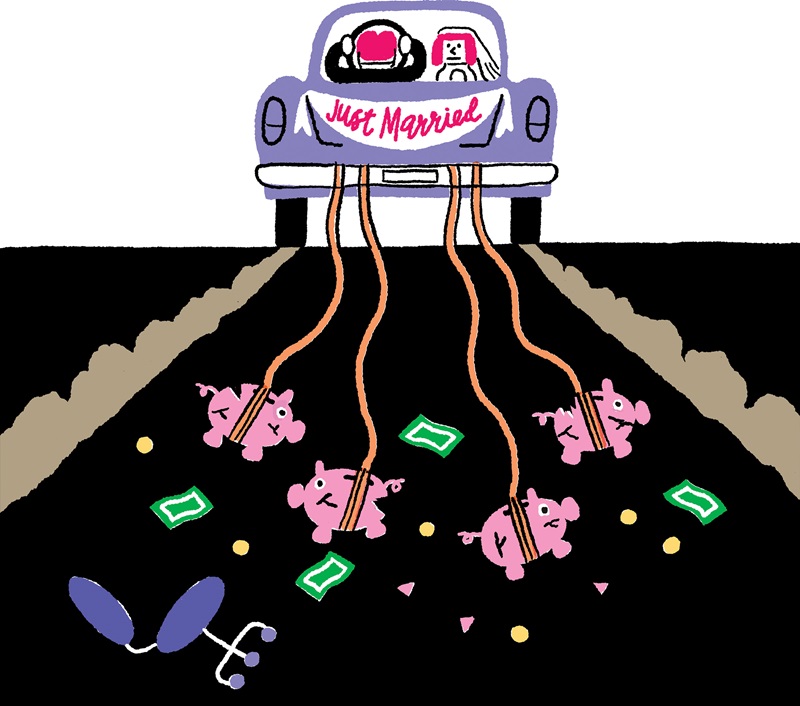

Since then, the percent of married women who work has almost tripled, to around 70 percent. To see why joint taxation matters, consider an individual, Dee, who earns $30,000 a year. Assuming Dee takes a standard deduction and has no other income or credits, Dee’s marginal tax rate is 12 percent—that is, if Dee earns $30,001 this year, Dee owes $0.12 in tax on that last dollar earned.

Now imagine Dee meets someone, falls in love, and gets married. Dee’s spouse makes $85,000. The couple files a joint tax return on their combined income of $115,000. Now if Dee earns $1 more next year, the tax on that $1 is $0.22—almost twice as high—just because Dee is married.2

The fact that couples are taxed on their combined income means that secondary earners (that is, the spouse who earns less money) often face marginal tax rates that are substantially higher than what they’d face if they were not married. Since it is still the case that husbands earn more than wives in many couples, this higher marginal tax rate is likely to affect women in particular. In Figure 1, Borella, De Nardi, and Yang show that women have faced higher marginal tax rates when married than when single.

Figure 1 shows the marginal tax rate in 1988 faced by four groups of women who were born between 1941 and 1945. It confirms that the marginal tax rate faced by women at a given income is higher when they are married than when they are single, no matter how much the woman earns or how much her spouse earns.

The largest difference in the marginal tax rate occurs for women who earn a small income. A single woman whose income was $500 per year had a marginal tax rate of -10 percent (for example, she received a refund due to the Earned Income Tax Credit), whereas a married woman earning the same amount faced a marginal tax rate between 14 percent and 21 percent, depending on her spouse’s income.

If higher marginal tax rates discourage people from working, then the dependence of the marginal tax rate on marital status is likely to affect secondary earners’ decisions about both whether to work and how much to work.

Marital status may affect how much secondary earners choose to work via another channel as well: the Social Security program. Under current law, married and widowed people can claim Social Security retirement benefits and survivor benefits based on their spouse’s contributions rather than their own. For secondary earners, this means that working less does not necessarily negatively impact their Social Security benefits, which reduces their incentive to work, the economists explain. Meanwhile, working more means paying more Social Security tax, which in many cases will have no effect on the secondary earner’s future Social Security benefits because of spousal benefits.

To analyze the impact of these marriage-related provisions of the tax code and Social Security program, Borella, De Nardi, and Yang conduct a policy experiment: What happens to labor force participation if these provisions are eliminated? How much do people work if their marginal tax rates and Social Security benefits do not depend on their marital status? The economists do this by creating a model of how much single and married people work and save over their lifetimes. Their model incorporates the possibility of marriage and divorce, child care costs, education, changes to wages, medical expenses, and the risk of death, as well as other factors that affect individuals’ decisions about how much to work and save.

To estimate a number of these elements, including marriage and divorce rates, wage processes, and medical expenses, the economists use data from two large U.S. population surveys run by the University of Michigan. They chose to study two groups: individuals born between 1941 and 1945 (the 1945 cohort) and those born between 1951 and 1955 (the 1955 cohort). The 1945 cohort has completed a large part of its life cycle; thus, data are available for both their working period and their retirement period. The 1955 cohort has also completed most of its working period while providing a useful contrast because the share of married women who participated in the workforce is significantly higher in this cohort than in the 1945 cohort. Thus, the effects of the policy experiment may differ for the two groups.

Using their model, the economists estimate what could happen if these marriage-based provisions are eliminated—in other words, everyone files an individual tax return and earns Social Security benefits based on their own earnings history. Because more people work as a result of these policy changes, the government collects more taxes, creating a surplus. So the economists lower the payroll tax rate by 2 percentage points, which balances the government’s budget.

Figure 2 shows that eliminating the marriage-based provisions has a big effect on the 1955 cohort: The participation of married women (gold line) in the workforce is 12 to 25 percentage points higher from age 25 to age 60. The average yearly earnings for women also increase a lot, by $5,000–$6,000 a year for married women and by about $2,000 for single women (gray line) for most of their working years.

The effects on married men are modest but noteworthy. The percent of married men (teal line) who are working during middle age increases a bit but, by age 65, their participation is 5 percentage points lower than it was in real life. The average yearly income of married men declines starting at age 55, suggesting that some are cutting back hours. Married men participate less and work less because their wives work more under these policy changes, and the couple’s increased savings allow the husband to retire earlier.

It is also important to ask what percent of people are better off if these policies are changed (and payroll taxes decline to balance the government’s budget). The economists find that in the 1955 cohort, 98.9 percent of couples, 100 percent of single men, and 70.9 percent of single women would prefer eliminating these policies. Thus, the benefits are widespread. Furthermore, for the single women and couples who prefer the current policies, the loss they would experience from the change is quite small. Importantly, the economists calculate these changes to people’s welfare assuming that the policy changes take place when everyone is age 25, when they enter the workforce. Thus, people have their entire working lives to take advantage of lower tax rates and can plan appropriately for retirement.

Lifetime impact on wages and savings

The joint taxation feature of the U.S. tax code is an unusual one. Much has changed since its implementation, and the result is a disincentive to work for secondary earners that likely was never imagined by lawmakers. But the current system has far-reaching effects across people’s lives. As the economists write, “This lower participation [of married women] reduces their labor market experience, which in turn reduces their wages over their life cycle.” It also reduces savings and contributions to retirement accounts.

While changes to the U.S. tax code over the past 10 years have attempted to harmonize the treatment of single filers and married filers, higher marginal tax rates on secondary earners have not gone away. Together with the spousal benefits and survivor benefits of the Social Security program, Borella, De Nardi, and Yang show that ending these policies could provide a meaningful boost to women’s participation in the labor force—and to the growth of the national economy as a whole.

Endnotes

1 Married couples can file taxes separately in the U.S. but, in most cases, filing jointly offers married couples a lower tax liability.

2 In the United States, taxes depend not only on wages but also on interest income, retirement contributions, and other factors. Marginal tax rates reported here assume the couple’s only income is wages and there are no retirement contributions. See how the marginal tax rates were calculated.

This article is featured in the Fall 2021 issue of For All, the magazine of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute

Lisa Camner McKay is a senior writer with the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute at the Minneapolis Fed. In this role, she creates content for diverse audiences in support of the Institute’s policy and research work.