Since the beginning of the pandemic, about 4,600 nursing home residents in the Federal Reserve’s Ninth District have died of COVID-19. The disease has also taken a tremendous toll on the already frail nursing home industry.

Besides losing existing residents, most nursing homes have admitted far fewer new residents while paying far more for labor and protective equipment. A majority are likely operating at a loss given national trends, and some may not survive.

“For the most part, we’re in a period of great uncertainty,” said Patti Cullen, president and CEO of the industry group Care Providers of Minnesota. “We don’t know … how long it will take for us to build back our occupancy and if there’s enough time before we have to close.”

Before the pandemic, occupancy throughout the Ninth District was at historic lows because of strong competition from other kinds of eldercare services, such as assisted living. Nursing homes also faced a host of other challenges from not being able to hire enough workers due to anemic Medicaid reimbursements. Many of those challenges got worse during the pandemic.

So far, the industry has avoided a wave of nursing home closures, but that is mostly because of federal aid, according to Stephen Taylor, who leads the nursing home consultancy at CliftonLarsonAllen. “Without continued aid, the issues that existed pre-pandemic will be exacerbated with the occupancy pressure,” he said in an email. “Unfortunately, many of the operators do not have the ability to weather a long occupancy rebound.”

Nursing homes have tried to adapt, for example, by adding assisted living to their offerings, but Taylor said he expects that more changes will be necessary to survive.

One of the consequences of more nursing homes closing is a loss of capacity that industry advocates say will be needed as baby boomers reach advanced ages and require around-the-clock care; the U.S. Census Bureau projects that the oldest population, those 85 and older, will grow by more than a third over the next decade. Rural areas have already seen this loss of capacity with more counties losing their last nursing homes, forcing seniors who need that kind of care to move far away from family and friends.

And nursing homes don’t have to close to be a problem; weak finances can lead to understaffing, which threatens the well-being of residents even in the absence of a pandemic.

Long decline in occupancy

Entering the pandemic, occupancy in Ninth District nursing homes was at its lowest since at least the mid-1990s (Chart 1), according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS); earlier data are not readily available. This decades-long decline has occurred even as capacity fell with 30 percent fewer beds and 15 percent fewer nursing homes.

The Ninth District includes Minnesota, Montana, North and South Dakota, northwestern Wisconsin, and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Occupancy trends are similar around the nation, and part of the reason is competition.

Nursing homes provide a lot of care for a lot of money, and not every senior needs it. In their heyday, nursing homes were the only option for most seniors who weren’t able to live independently. Seniors now have many more options for just the amount of care they need for much less money. In Minnesota, the median daily rate of a shared room at a nursing home is $363, compared to the $33 median hourly cost of a home health aide, who typically is hired for a few hours a day, according to long-term care insurer Genworth. The median daily cost of assisted living, which is housing with varying levels of service, is $141.

“Our assisted living communities have skyrocketed,” Cullen said. “Go down any street and there it is. There’s an apartment complex where seniors live, or they’ve done co-op models, or they’ve done senior communities that have both assisted living and nursing homes.”

These other options, along with a trend toward seniors staying healthy for more of their golden years, have made it harder for nursing homes to grow. Even as the senior population from which they draw keeps rising, the number of nursing home residents keeps falling (Chart 2).

Cullen said nursing homes in rural areas have had it worse, closing at a faster rate than their urban counterparts, in part, because they lack an economy of scale with their smaller size. In the Ninth District, nursing homes averaged 56 beds in rural areas and 84 in urban areas, according to CMS data. The data also show that rural areas suffer from lower occupancy and a greater loss of capacity as measured by the number of beds (Chart 3).

Anemic Medicaid reimbursements

But not all occupancy is equal as far as revenue is concerned.

Long-term residents, who make up the bulk of the nursing home population, are money losers. Medicaid covers most of this population,* and reimbursements are usually less than the cost of care. Short-term residents recovering from surgery, despite their much smaller numbers, are the money makers. Medicare covers most of them, and reimbursements are generous enough to subsidize the Medicaid-covered residents.

But Medicare reimbursements have been cut over the years, contributing to the shrinking nursing home margins. In the early 2010s, overall margins were about 2 percent nationwide but had fallen to 0.6 percent in 2019, according to data from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Margins were actually negative in 2018.

Low margins have led to lower wages, which makes it hard to hire workers needed to remain open.

Taylor said it’s especially challenging to hire certified nursing assistants, who work in difficult conditions but whose wages are similar to those of restaurant and retail workers. “On a wage perspective alone, [nursing home] operators have a lot of competition when they are looking at recruiting for those positions. The simple reality is that inadequate Medicaid rates make it very difficult for operators to compete for talent.”

Big problems got bigger

COVID-19 made many of the nursing home industry’s preexisting conditions much worse.

Occupancy fell at the start of the pandemic when hospitals canceled elective surgeries, reducing to a trickle the flow of Medicare-covered residents to nursing homes. Even after elective surgeries resumed, many older patients did not reschedule right away for fear of contracting COVID-19. Nursing homes converted existing rooms to quarantine wards, reducing capacity. They imposed restrictions on visitation to prevent outbreaks, prompting many families to steer loved ones away from nursing homes to swing beds at hospitals where visitation policies were more liberal.

In the fall, when a COVID-19 infection surged around the nation, CMS records show occupancy plunging even further (Chart 4).

Falling occupancy meant falling revenue. Expenses, however, went the other direction.

The price of masks, gloves, gowns, and other personal protective equipment (PPE) rose by double digits as health care providers and the general public competed for protection from the COVID-19 virus. Nursing homes also bore the cost of testing. In areas with high infection rates, the federal government required staff to be tested as often as twice a week. At about $100 per person, Cullen said those costs add up quickly.

Labor costs grew as nursing homes offered “hero pay” in the form of wage hikes or bonuses to retain existing staff, according to Cullen. Costs grew even more when staff members were quarantined because of COVID-19 exposure and temp agencies were brought in to fill the gap. The average nursing assistant’s wage in Minnesota is around $13 to $14 an hour, but it was not uncommon for temp agencies to be paid $40 an hour for a temporary replacement.

For many nursing homes, state and federal aid was a lifeline. The CARES Act, for example, provided $9.4 billion specifically for nursing homes, which could also access other aid such as Payroll Protection Program loans. The state of Minnesota has provided $3.9 million in emergency funding. According to Cullen, nursing homes that took advantage of whatever aid program they qualified for would have had “plenty of money” to pay for expenses.

After the storm

But the aid won’t last, and Taylor said he expects the nursing home industry to contract further, continuing a pre-pandemic pattern.

Cullen expressed particular concern for rural nursing homes. When a COVID-19 outbreak occurs, it typically kills a handful of residents in any single facility, but these handfuls represent a bigger chunk of a small nursing home’s occupancy. And, in sparsely populated rural areas, it takes longer to replace those lost residents.

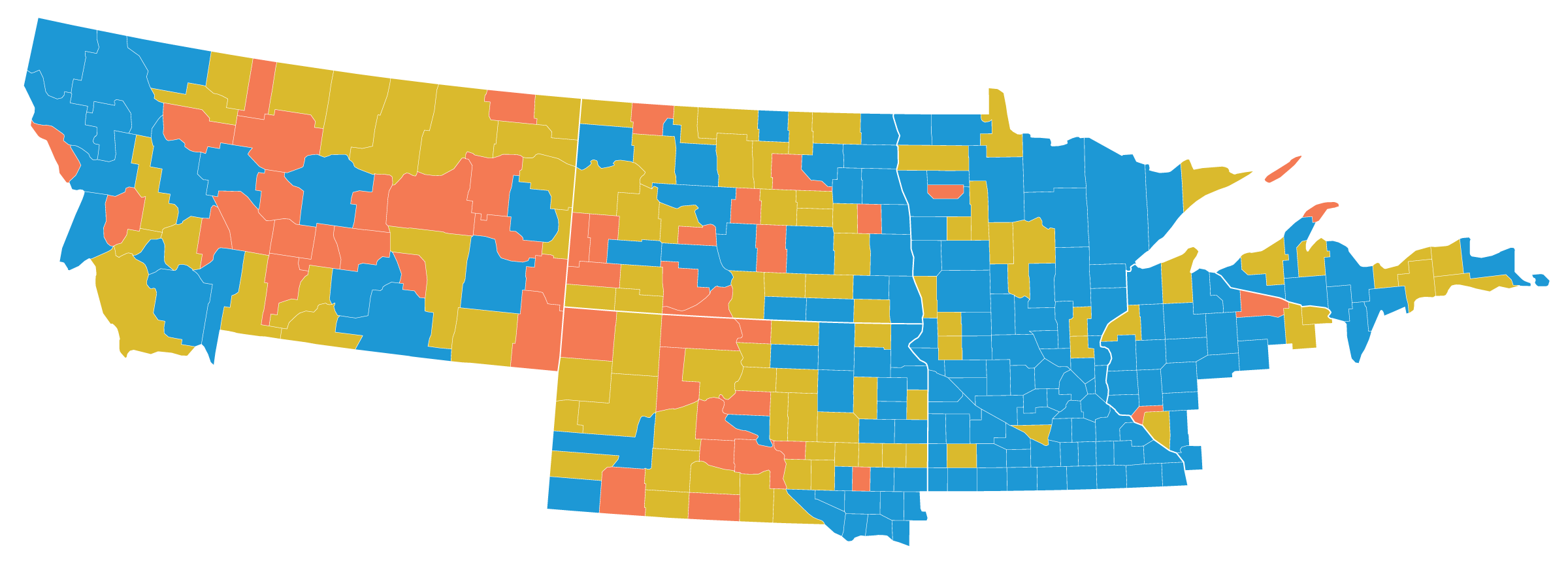

If more nursing homes close, it will be harder for rural seniors to get nursing services. As of the start of 2021, there were 42 rural counties with zero nursing homes certified by CMS and 82 with just one nursing home; together, they cover most of Montana and North and South Dakota (Chart 5).

In the long run, nursing homes will have to adapt to survive.

Many owners have already diversified their business, such as adding assisted living units, home health agencies, and pharmacies, according Taylor. But the pandemic shows that more adaptations are needed, such as investing in technology to improve staff efficiency, increasing PPE stockpiles, and modifying interior airflow to reduce the risk of airborne diseases spreading. Some nursing homes strengthened their relationship with local hospitals by finding space for the hospitals’ COVID-19 patients.

Governments will have to step up, too, to address the low Medicaid reimbursements, Cullen and other industry advocates say. The industry’s low margins have made it hard to invest in better care and to prepare for the next pandemic.

“We learned a lot of lessons from this pandemic,” Cullen said. “It taught us that we were vulnerable. This whole sector is vulnerable to bad things happening in our settings because we have workforce shortages and we’re undercapitalized.”

Endnote

* The cost of nursing home care is so high that many seniors requiring such care deplete their savings and must rely on government aid.

Tu-Uyen Tran is the senior writer in the Minneapolis Fed’s Public Affairs department. He specializes in deeply reported, data-driven articles. Before joining the Bank in 2018, Tu-Uyen was an editor and reporter in Fargo, Grand Forks, and Seattle.