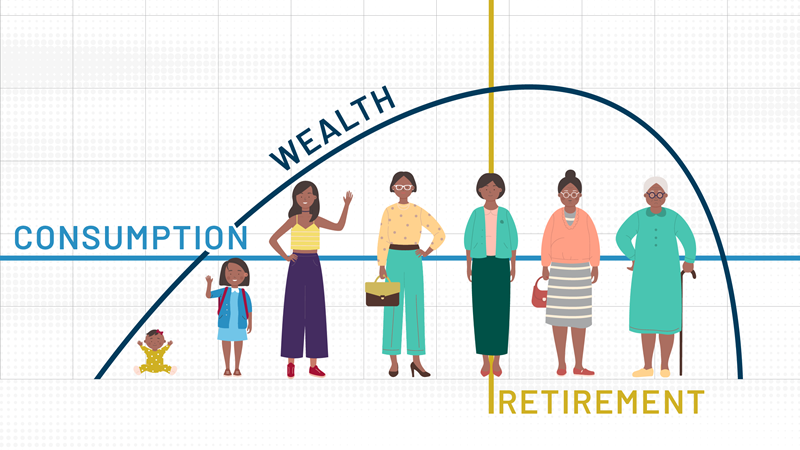

From retirement planning to modeling the growth of nations, the last 70 years of economics have been shaped by the “life cycle hypothesis.”

Stated broadly, the life cycle hypothesis holds that people make financial decisions to smooth out their consumption over a lifetime. After borrowing early in life and earning, saving, and insuring themselves during middle age, people deplete those resources after retirement, anticipating their remaining years of life and parsing out their resources accordingly. The concept netted a 1985 Nobel Memorial Prize for economist Franco Modigliani, who developed it with his then-student Richard Brumberg.

In the words of more recent Nobel-winner Angus Deaton, the life cycle hypothesis “remains an essential part of economists’ thinking.” Yet as essential as it is, the basic model begs for elaboration.1

For one thing, we know that our so-called golden years can be anything but a smooth and predictable glide to the finish. These complex, dynamic risks we face later in life have become a major focus for Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute consultant Mariacristina De Nardi, the Thomas Sargent professor of economics at the University of Minnesota.

“People are living longer. Health issues are affecting economic outcomes, affecting medical expenses, affecting longevity,” De Nardi said. “People are ending up in nursing homes for long periods of time and having to pay those large costs. All of this is becoming more prevalent for society and more of a risk from the standpoint of the individual.”

Longer lives, fewer births, and falling immigration mean that by 2035, 1 in 5 Americans will be over 65. For the first time, American seniors will outnumber children.

In a pair of recent Institute Working Papers, De Nardi and her co-authors set out to untangle saving and spending patterns that emerge amid our highly uncertain end-of-life journey. Contemplating sickness and mortality can be uncomfortable for some, De Nardi said. But “once you start thinking about this period of more mature age and its challenges, you start uncovering different risks and potential responses that make for a very interesting study.”

A life cycle puzzle: saving after retirement

In the basic lifecycle model, retirement is when saving flips to “decumulating”: People stop building wealth and start spending it down. If we simply draw a statistical line between retirees and everyone else, this trend is indeed what we see. In the latest Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, for example, median wealth steadily increases for every age group until the final one, ages 75-plus, where it drops.

However, more detailed data tell a more nuanced story—one that De Nardi explores in her Institute Working Paper “Why Do Couples and Singles Save During Retirement?” (with Eric French, John Bailey Jones, and Rory McGee2). Using survey responses from a dataset called “Assets and Health Dynamics of the Oldest Old,” the economists find that the median middle-income U.S. couple keeps building wealth well into their 80s. High-income couples keep saving even longer. High-income singles stop saving earlier than couples, but still save well beyond retirement.3

Why are many people still piling up savings when the life cycle hypothesis says they should be spending?

Part of the answer is that health-related expenses have become heavily compressed in our final years, as we live longer and face expensive end-of-life care. An estimated 1 in 3 American seniors will need some form of long-term care before they die. Previous work by De Nardi and co-authors finds that at age 70, Americans face an average of $122,000 of remaining medical spending, with a 5 percent chance that expenses will top $300,000.

The researchers highlight a striking fact: As people age through their 70s and into their 80s, the share of lifetime medical spending still ahead of them barely decreases. “The longer you live, the more frail you are, and the more expensive it is to be alive because you’re more likely to be in a nursing home,” De Nardi said.

So singles and couples with sufficient means keep on saving long past retirement, in part to better prepare for this massive, late spike in expenses. Long-term care insurance products exist to help smooth out these risks. But the current market is widely considered to be dysfunctional, with few Americans buying coverage and insurers exiting that line of business. The economists’ analysis finds that rather than invest in insurance during their prime working years, many people continue to self-insure into their 80s.

The profound (financial) pain of widowhood

Couples save in preparation for a further complication: the near certainty that one spouse will die before the other. Married women in the researchers’ dataset live more than four years longer than married men.4 Beyond the emotional loss, De Nardi’s research highlights just how deeply a spouse’s death affects households financially.

On average, the wealth of a couple who experiences the death of one spouse falls by $160,000 compared to a couple who does not. The financial paths of these couples begin to diverge around six years before the death, accelerating in the two years before it and continuing at least four years after.

One driver is the loss of income; Social Security and other survivors’ benefits do not fully make up for what is lost when the spouse dies. Another big factor, naturally, is medical and death-related costs, such as funeral and burial. These costs average $27,000 more for couples where one partner dies, with the majority of expense coming in the two years before the death.

However, the researchers find that medical and death expenses are only part of the story, explaining less than 20 percent of the total drop in wealth. Another factor turns out to be more important. Nearly half of the loss arises from wealth that is transferred to children or other heirs while one spouse is still living. Rather than the remaining spouse continuing to spend down the couple’s full wealth until his or her own death—which the basic life cycle hypothesis might suggest—the death of one spouse appears to jump-start the bequest process for the household.

The economists calculate that medical, death, and bequest expenses together explain about two-thirds of the wealth gap that arises around the death of a spouse. That still leaves a substantial role for lost income and other factors that further erode the financial cushion of the widow or widower. All told, much of a couple’s original wealth is typically gone by the time the second spouse dies.

You can’t take it with you (but you can leave it for others)

Like classical economic theory, the life cycle hypothesis presumes that we derive utility from our own consumption. Yet people do give money away—during and after their lives—to charities and to heirs. Modigliani himself acknowledged and reckoned with the undeniable fact of bequests (even as his basic life cycle model consciously set them aside).

De Nardi and her co-authors work to measure the importance of the “bequest motive” in the savings of older people, and to break this motive into different parts.

Not surprisingly, their data show bequests are a luxury good, driving the financial decisions of middle- and high-income couples and high-income singles. Bequest motives appear to be more important than medical expenses for couples, who are generally wealthier than single households and leave bequests on two primary occasions: the death of each spouse. The economists find the bequest motive inspires high-income couples to build 34 percent more wealth than they otherwise would; middle-income couples save 16 percent more than otherwise.

They also highlight how the bequest motive interacts with late-in-life medical expenses in a powerful way—more powerful, in fact, than either factor on its own.

Our own lifespan and the medical costs we will face are impossible to know. Bequests provide a buffer against this uncertainty, by reducing the opportunity cost of potentially saving more than we need. If we turn out to save too much, De Nardi said, “it’s not really wasted—at least I’m happy somebody will get it. What the bequest motive does is reduce the cost of insuring yourself against a long life or expensive medical conditions.”

Couples, especially, would save much less if not for this potent interaction. Knowing that any of our leftover savings will be available as a bequest increases the appeal of self-insuring, versus options like long-term care insurance—which could help explain why such insurance remains unpopular. It also suggests that longer lives, more uncertainty, and more expensive end-of-life care could actually increase the likelihood and size of bequests. These factors encourage more precautionary savings, which means there will be more left over if these savings are not needed.

The decreasing “ability to enjoy life”

De Nardi shifts the lens from saving to spending for another recent Institute Working Paper: “Why Does Consumption Fluctuate in Old Age and How Should the Government Insure it?” (with Richard Blundell, Margherita Borella, and Jeanne Commault5).

Our spending is, of course, a function of how much money we have. But it also depends on how much enjoyment (or “utility”) we get from spending that money. The authors highlight an aspect of growing older that they say deserves more attention: As our health declines, we get less bang for our buck.

“Thinking about how your ability to enjoy life, and to enjoy your resources, changes—that’s something economists haven’t really discussed a lot,” De Nardi says. “We think about income risk and we think about resource risk, but we haven’t thought all that much about how your ability to enjoy your money changes with health.”

The economists draw on surveys that track the health and spending of thousands of U.S. seniors over a recent 12-year period.6 The survey data include common health conditions and self-reported struggles with a menu of “Activities of Daily Living,” such as difficulty getting out of bed, climbing a flight of stairs, getting dressed, or picking up a coin.

For the seniors in the data, changes in health strongly affect consumption of nondurable goods and services. While higher-income households cut back on leisure activities and other luxury goods, lower-income households also cut back on necessities like food and car repairs.

The economists’ model allows them to isolate two effects driving the drop in spending. First is the fact that health shocks can be expensive, which diverts money from other purchases (the “resource effect”). The other effect is a change in the “marginal utility of consumption”—how much enjoyment we get from our purchases.

While the resource effect plays a small role for lower-income seniors, the more powerful factor by far—for all households—is that health issues decrease the utility we derive from spending money. The things we might have planned for our retirement, from international travel to puttering in the garden, don’t bring us the same joy.

“If you have mobility issues, you probably don’t want to go and hike Mount Kilimanjaro,” De Nardi said. “If you can’t eat much, a five-star French restaurant is not how you want to spend your money.”

Extensive implications for policy

Understanding how we make decisions amid the uncertainty and risks of old age should assist with the ultimate, practical question: How do we help?

In the case of health and spending, “if health mainly reduces the marginal utility of consumption, giving resources to a person affected by a negative health shock is not an effective policy,” the authors write. “Optimal insurance depends on why consumption fluctuates.”

With regard to saving patterns, untangling why many people keep building savings into retirement, the effects of widowhood and the bequest motive, and how all of these choices vary by income should inform better ways to insure against the uncertain and daunting expenses we face at the end of life.

These findings—and many others across De Nardi’s body of work on aging, health, and income risk—further interact with the existing safety net of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. The landscape is complex. De Nardi credits her colleagues and graduate students working on promising papers, but says there is plenty of room for researchers eager to build out a life cycle model that looks more like real life—including our final years.

“I think there is getting to be more of an interest,” De Nardi said. “But given the scope of the questions and the problems, and the cost of paying for these programs, we are still far from having enough people working on it.”

Endnotes

1 It is important to acknowledge that Modigliani himself appreciated the importance of post-retirement savings, bequests, and other extensions beyond what he called the “pure” or “stripped down” life cycle hypothesis. His general response, for example in his Nobel Prize lecture, was that these factors were vital to consider, but omitting them did not compromise or substantially erode the basic model’s explanatory power for many questions.

2 French: University of Cambridge. Jones: Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. McGee: University of Western Ontario and Institute for Fiscal Studies.

3 The economists divide couples and singles into high-, middle-, and low-income cohorts. The savings trends discussed here do not surface for low-income singles and couples, who begin and end retirement with little savings, relying on Medicaid for late-in-life care.

4 The dataset the researchers use does not identify partnered-but-unmarried couples. Their present analysis excludes same-sex couples, to isolate the important role played by lifespan differences of women and men.

5 Blundell: University College London, Institute for Fiscal Studies, and Center for Economic and Policy Research. Borella: Università di Torino and CeRP-Collegio Carlo Alberto. Commault: Sciences Po.

6 The economists analyze spending on “nondurable goods,” such as food, car repairs, leisure activities, and home and garden supplies.

Jeff Horwich is the senior economics writer for the Minneapolis Fed. He has been an economic journalist with public radio, commissioned examiner for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and director of policy and communications for the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. He received his master’s degree in applied economics from the University of Minnesota.