Located in an isolated community with a shrinking population, the Pondera Medical Center in Montana’s Hi-Line region faced an uncertain future a few years ago, so its board hired consultants to help with planning.

“They said we probably wouldn’t be able to make it past five to six years unless we started working with somebody bigger,” said Bernard Ries, who chairs the hospital’s board.

With fewer residents in Pondera County, the hospital will have fewer patients, which means less revenue even as the cost of recruiting and retaining health care workers rises, he said. Many small rural hospitals have had to close in recent years, he said, and the board wanted to ensure access to care for area residents.

The “somebody bigger” came in the form of Logan Health, a health care system located just on the other side of the mountains in Kalispell, Montana. Logan was starting to build out a regional hospital chain and the Pondera hospital became one of four hospitals that joined the chain starting in 2020.

Over the past several decades, hospital consolidations and the resulting decrease in health care competition have received a good deal of scrutiny as more evidence emerges of their detrimental effect on health care costs and, in some cases, quality. But in many markets that are so small they can barely support one hospital, consolidation can be a way to preserve access to health care even if that leads to the loss of local control over health care options.

“Everyone wants to maintain their own independence,” said Brad Gibbens, acting director of the Center for Rural Health at the University of North Dakota. “The reason why they go into a system is they reach that point where they don’t have the confidence that they’re going to stay open as an independent and they look at the various resources and protection they can have by being part of a system. It’s a reluctant rational decision.”

Consolidation trends

While consolidation is commonly thought of as the purchase of a hospital by a hospital chain, there are other types of consolidation deals that are less permanent. Hospital chains sometimes sign agreements to manage or lease another hospital, which can offer independent hospitals some or most of the benefits of consolidation without a change in ownership.

For independent hospitals, these agreements are often preferable because they allow the hospitals’ boards to retain some control and the possibility of resuming full control when the agreements expire.

In the Ninth District, more than half of the hospitals1 that consolidated between 2011 and 2020 were independent. Among those independent hospitals, more than a third entered an agreement that didn’t involve an outright purchase by a chain, according to an analysis of Medicare and other records. Chain hospitals that consolidated were all purchased by other chains.

The district chains most active in consolidating independent hospitals were Avera Health, based in Sioux Falls, South Dakota; CentraCare Health System, based in St. Cloud, Minnesota; and Billings (Montana) Clinic. Each consolidated five independent hospitals during the 2011–20 period, and together they account for a third of all independent hospitals involved in consolidation. Billings Clinic, in particular, has management rather than ownership relationships with all the hospitals in its chain, except for the main Billings hospital.

A national comparison is difficult because information about management agreements is not as readily available as information about ownership. Between 2011 and 2020, around 40 percent of U.S. hospitals that changed ownership were independent, according to Medicare data.

The Ninth District has seen very similar ownership trends. The difference is that most of the independent hospitals purchased by chains have been small (25 or fewer beds), rural, or both. Nationally, most independent hospitals that were purchased are larger (more than 100 beds), urban, or both.

For the most part, consolidation deals involving independent hospitals have carried on at a steady pace in the Ninth District (Figure 1). The exceptions were spikes in 2012 and 2013, which followed the passage of several health care reform laws that penalized hospitals for conditions such as poor-quality care, and in 2020, during the most difficult phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, when hospitals were unable to offer elective procedures. The challenges of operating a hospital increased in both cases, especially for small, independent hospitals with few resources, making them ripe targets for consolidation, according to economists.

As more independent hospitals consolidate, the Ninth District market has become more dominated by chains. In 2010, 45 percent of hospitals were independent (Figure 2). As of the end of 2022, only 28 percent were independent.

At the same time, consolidation has not led to a significant decrease in competition. Many hospital markets haven’t been competitive for years.

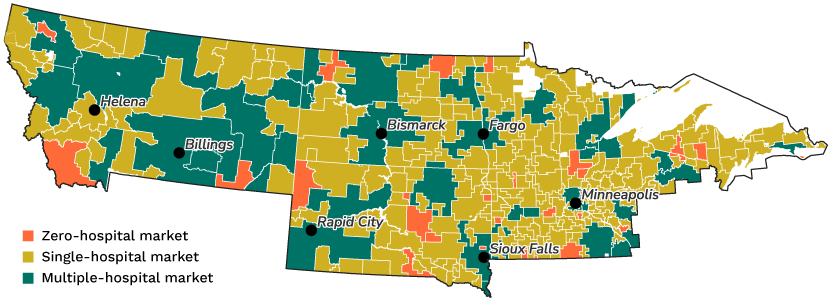

A common framework used by economists to analyze health care competition is based on two tiers of markets.2 Local markets are served by local hospitals providing basic medical services that most patients prefer to receive close to home, such as emergency departments. Regional markets, made up of multiple local markets, are served by regional hospitals providing more advanced medical services.

Out of 293 local markets in the Ninth District, more than 80 percent had just one hospital in 2011. Out of 21 regional markets, nearly 40 percent had just one regional hospital, defined here as those with more than 100 beds, and two-thirds had two or fewer regional hospitals. Nationwide, 74 percent of local markets had just one hospital and 9 percent of regional markets had just one regional hospital in 2011.

These figures increased slightly by 2020 (Figure 3). The exception was the share of U.S. local markets with just one hospital, which fell to 71 percent mostly because those markets lost their only hospital; they went from being counted as single-hospital markets to being counted as zero-hospital markets.

Seeking protection

The drivers of this trend are the same ones that led the Pondera hospital to consolidate with Logan Health: a shrinking population, slowing economy, higher costs of care, and a shortage of health care workers.

Among Ninth District hospitals involved in consolidation, independent hospitals tend to be in counties with declining populations, and they tend to report higher expenses than chain hospitals before they are sold to a new chain. Patient numbers tend to be in decline at independent hospitals but less so than at chain hospitals involved in consolidation.

But even with such negative trends, independent hospitals that consolidate aren’t necessarily in danger of immediate closure. Many recognize that failing hospitals are not attractive consolidation targets, so they must seek out a chain while they’re still financially healthy.

Ries said that’s the advice the consultants offered his board. Had they waited until the situation was dire, he said, any chain they approached would have been able to lay down the rules and they would have had no choice but to accept. “We wanted to write our rules. And the main thing was to protect our assets, and protect our medical services, and make sure we didn’t lose services.”

Chains can offer smaller hospitals the resources to keep their doors open and potentially to grow their services.

Small independent hospitals often have a harder time raising capital; their size can make them seem riskier to financial institutions. Chains tend to have an easier time raising capital, and they tend to invest heavily in newly acquired hospitals. Independent hospitals can also benefit from the efficiencies of a chain through shared overhead costs and operational expertise.

Ries said the Pondera hospital’s small patient volume meant it could never afford the cost of implementing electronic health records (EHR) mandated by Congress in 2009. The penalties assessed by Medicare were more affordable. But Logan Health already had an EHR system and was able to bring its new partner into the fold with little trouble.

Another big challenge for the Pondera hospital was recruitment. The hospital is in a very rural area that doesn’t attract many newcomers. Logan Health, located among mountains that do attract new residents to the state, has less difficulty. Under a yearslong agreement, Logan has sent management trainees to be Pondera hospital’s chief executive. The smaller hospital was, effectively, a stepping stone for employees of the larger hospital.

But one of the reasons chains seek out smaller hospitals for consolidation is to improve efficiency. That can mean consolidating medical services at a few hospitals instead of offering them at every hospital. An independent hospital that joins a chain risks losing those services to the chain’s other hospitals.

Many chains have consolidated birthing services because of declining births in the U.S. For example, Allina Health System in the Twin Cities has, in recent years, ended nonemergency deliveries at three of its smaller hospitals and now refers expectant mothers to two of its larger hospitals. For expectant mothers in the communities that lost birthing services, this change can mean a 30- to 40-minute drive.

In some cases, inpatient services are consolidated, leaving hospitals without the function that defines them. For example, Mayo Clinic moved all inpatient services except an emergency room and behavioral health unit from its hospital in Albert Lea, Minnesota, to its hospital in nearby Austin in 2019.

Gibbens said consolidation can be a tough decision for independent hospitals. “The trade-off is we either go into an affiliation and we may provide less services, but if we don’t go into an affiliation, we close and we provide absolutely no services.”

Local control in the balance

Many independent hospitals considering consolidation are keenly aware that they risk losing the services so prized by their communities. That’s why so many choose to enter into a management agreement with a chain instead of being acquired by the chain.

When Logan Health brought the first draft of the consolidation agreement before the Pondera hospital board, Ries said they rejected it because it was too vague on maintaining services. “We went around and around probably for a good year before we came to one that everybody could kind of agree on.”

The final agreement gave the local community some say over budgeting and veto power over any reduction in services.

Crucially, while it gives Logan Health ownership of the nonprofit that runs the hospital, the physical facility remains under local ownership.

“If the county still owns the buildings and this thing falls apart, we still have a hospital,” Ries said. “When I’m on the street and somebody finds out I’m on the board, they say, ‘We can’t lose that hospital.’ People believe in our hospital and they don’t want to see it go away.”

Endnotes

1 The term “hospital” in this article refers to a short-term general hospital, meaning they offer a mix of services rather than specializing in certain conditions or patient populations. Also excluded are hospitals not open to the general public, such as Veterans Affairs hospitals.

2 Hospital markets are defined by the Dartmouth Atlas, a commonly used reference for health economists. These markets are based on where patients in each ZIP code usually go for certain medical services.

Tu-Uyen Tran is the senior writer in the Minneapolis Fed’s Public Affairs department. He specializes in deeply reported, data-driven articles. Before joining the Bank in 2018, Tu-Uyen was an editor and reporter in Fargo, Grand Forks, and Seattle.