The extent of income inequality is a defining characteristic of a society. How unequal a society is, and how that inequality has changed over time, can tell us a lot about opportunity and inclusion, about power and influence.

“Measuring income inequality is making a judgment about the distribution of income,” said John Voorheis, co-author of a new Institute working paper on the topic. “I think a lot of us have egalitarian intuitions where we think that resources should be shared broadly across people. In that sense, then, if income inequality is rising, maybe that’s something we should care about.”

Indeed, income inequality in the U.S. has been rising. Since 1980, real income of the bottom 50 percent of the population has grown about 20 percent. Meanwhile, the top 10 percent have enjoyed 145 percent growth.

Comparing average incomes of large groups of people is a start, but the approach has limits. Averages hide important differences both across groups and within groups. Who is the average Black American, or the average Minnesotan? Comparing incomes not just at the mean or median but across the full income distribution shows where inequality is growing or narrowing, who is flourishing and who has been left behind. Ultimately, this lets us identify more precisely where inequality exists, an essential step in diagnosing what is causing inequality.

A rich, new dataset that combines income from tax returns with demographics from the U.S. census allows Institute visiting scholar Kevin Rinz and co-author Voorheis to provide a new and detailed picture of inequality. Their data, which they’ve shared publicly, can be used to compare income distributions across states, by gender, and by race.

Why income inequality matters

In addition to ethical concerns over fairness, inequality has practical economic, political, and social consequences. Some research suggests that higher levels of income inequality reduces a country’s aggregate economic growth because it decreases household spending and limits educational opportunities for the children of the less well-off. The unequal distribution of income constrains how much the pie grows for everyone.

In a country as large as the United States, with a federal system of governance, regional inequality matters too. Just over half of federal revenue comes from individual taxes—a share that has increased as corporate taxes have declined. Which states are net contributors and which states are net receivers of federal dollars is in large part a function of the incomes of the residents of the states. Incomes also impact local housing prices, and how housing prices vary across the country plays a role in where people can afford to live—and thus what labor market and other opportunities they might have access to. How one state performs, Rinz noted, “doesn’t just affect that state. It affects the populations of other states, the mobility among and between states, the location of economic activity, and possibly the productivity of firms and the varieties of products available.”

More generally, Institute advisor Luigi Zingales warns, a situation in which political and economic forces are captured by a wealthy few who grow increasingly rich while leaving others behind may lead to the rise of anti-capitalist populism—an outcome that further harms opportunity, innovation, and growth. Research by Voorheis and political scientists Nolan McCarty and Boris Shor investigates a connection between income inequality and political polarization, two phenomena that have been on the rise in recent decades. They find that legislatures in states with higher income inequality are more polarized than states with less inequality.

Comparing income distributions across states

Because income inequality is a key to understanding a variety of economic outcomes, it is important to be able to describe that inequality well. Previous analyses often relied on survey data, such as the American Community Survey and the Survey of Consumer Finances. But such surveys have limitations, particularly when it comes to high earners. First, high earners tend to underreport their income on surveys—perhaps on purpose, to seem more “average,” or because they focus on only one income source. Second, to preserve anonymity, many surveys use “top coded” data, meaning that respondents who report income above a certain value will all be assigned that top value.

By using income data from every individual who files IRS Form 1040, Rinz and Voorheis’ data is better able to capture earners at the top of the income distribution. The economists combine this data with demographic data from the Social Security Administration and race/ethnicity data from the Census Bureau’s Best Race and Ethnicity Administrative Records.

Using their new dataset, Rinz and Voorheis came up with an elegant measure that captures how similar (or not) state income distributions are to each other. Draw a chart with two lines, one that plots the national average income at each percentile of the income distribution, and one that plots the average income for a single state, say Minnesota (see Figure 1). Take the difference between the two lines at every point along the distribution and add that up. This is their “similarity measure”—a measure of how similar Minnesota’s income distribution is to the national one.

Then, repeat the process for each state and add up those 50 numbers for a single “similarity measure” of the 50 state income distributions at a particular point in time. Comparing similarity measures over time is one way to assess whether state income distributions, as opposed to just average or median incomes, are becoming more or less similar to each other.

Slow but steady income convergence—except at the top

By calculating a similarity measure for each state for each year in their dataset, Rinz and Voorheis show that state income distributions grew more similar between 1969 and 1979, but since then, they have been slowly moving apart. Rinz and Voorheis then calculate similarity measures for different parts of the income distribution to determine whether higher-income, middle-income, or lower-income people drive the divergence. They find that state income distributions actually have converged over the past 40 years for the bottom 85 percent of the income distribution.

At the top, however, state incomes have become less similar (Figure 2). In fact, the top 1 percent of the income distribution accounts for half the total divergence. Among the very rich, inequality across places is growing: The incomes of the wealthiest people in the wealthiest states are growing faster than the incomes of the wealthiest people in less-wealthy states. Among everyone else, inequality is diminishing, though slowly.

Source: Rinz and Voorheis, State-Level Income Distribution Data.

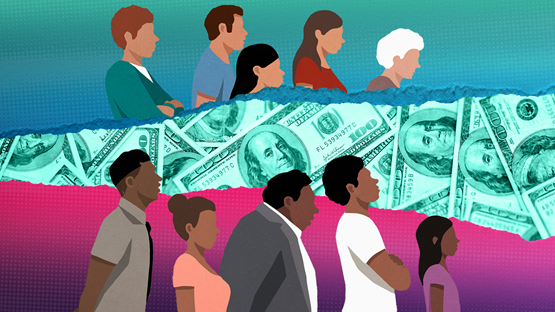

New evidence on the Black-White income gap

With the income distribution for every state in hand, Rinz and Voorheis then start to look at the distributions of different groups within states. Do all groups in high-income states earn above-average incomes? Or only some groups? For example, Connecticut has the highest average income in the country. Are the income distributions of both Black and White individuals higher than the national distribution in Connecticut?

The answer is no. Across states, there is a clear ordering: White residents of high-income states have the highest incomes; next are White residents of low-income states; then Black residents of high-income states; and finally, Black residents of low-income states (Figure 3).

In even the lowest-income states, White incomes are more or less in line with the national distribution. And in even the highest-income states, Black incomes are below the national distribution. This analysis shows that the Black-White income gap at the national level is not due to the fact that Black Americans tend to live in states with lower incomes; rather, other forces are at play.

“It was striking to see more explicitly how consistently Black income distributions lag White income distributions,” Rinz said. “It’s not limited to certain states. It’s not limited to certain parts of the income distribution. It’s everywhere.”

In light of this finding, it is perhaps not surprising that the divergence at the top of states’ income distributions is driven specifically by White incomes: It’s the wealthiest White people in the wealthiest states whose incomes are growing faster than everyone else’s.

Rinz and Voorhies’ data can also be used to investigate which states have larger or smaller gaps between the income distributions of their Black residents and White residents. Figure 4 shows the gap between the White average income and Black average income for the middle quintile—that is, the 41st to 60th percentile—in each state. Hawaii, West Virginia, and Montana have the narrowest gaps, though even in those states, the gap is large, around $20,000. California, Connecticut, and New Jersey have the largest gaps.

Next steps: Identifying causes

By comparing incomes across the full income distribution—of different states, of White and Black households—Rinz and Voorheis identify patterns of inequality not captured by analyses of averages. With this information, researchers can then start to ask, What explanations make sense of these facts?

“I think if you take the facts in our paper seriously,” Rinz said, “for any proposed mechanism, you would want to ask, How would that cause top incomes to become less similar and why would that apply primarily to White earners?” For instance, what role might fast-growing wages in the IT sector play, or local regulations on housing supply that drive up home prices? Of course, there is likely to be more than one factor at play, including a legacy of racial discrimination.

Because identifying where inequality exists is key to determining its causes—and solutions—it is valuable to continue the work of creating new measures of inequality across places and people. Rinz and Voorheis are contributors to a joint Census Bureau and Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute project to assemble localized measures of earnings and income. This large, detailed dataset will be of use to answer many new questions. For instance, what is the race/ethnicity composition of the top 2 percent of men with the highest incomes in Minnesota, and how does it compare to the top 2 percent of women? In what regions have women experienced the greatest income mobility? The new dataset will be made publicly available on the Institute website later in 2023.

This article is featured in the Fall 2023 issue of For All, the magazine of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute

Lisa Camner McKay is a senior writer with the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute at the Minneapolis Fed. In this role, she creates content for diverse audiences in support of the Institute’s policy and research work.