As he tells it, Illenin Kondo’s childhood in Togo had many advantages: Relatively well-to-do parents who cared deeply about his education. Early exposure to five languages, including French and English. A love of learning—especially science—and a gift for numbers.

But in West Africa, as much as anywhere, history and institutions press against the universal desire to shape our own destinies. When Kondo was in elementary school, his family fled the country for many months amid a political crisis and military repression. When his education got back on track, he recognized he would need to leave Togo eventually, if he could.

“When institutions fail, individuals are caught between either working hard against the institution, giving in, or escaping,” Kondo said. “If I can’t change the institution, I need to carve a path for myself.”

Even his family’s resources and best efforts contended with struggling institutions. “In 10th grade I was in one of the best high schools in the country, hands down,” Kondo said. “But there were still 70 or 80 of us in the classroom. I never entered a chemistry lab until I went to a college abroad.”

Kondo’s exam scores qualified him for a substantial college scholarship from the Togolese government. Still, institutions threatened. The scholarship was mired in bureaucracy. Kondo left for France with a plane ticket that his mother, who had not been paid in months, bought with a loan—and with the faith she could dislodge the scholarship eventually.

A year later, she did. And Kondo made it count. He completed his degree in electrical and computer engineering at one of France’s premier engineering schools, a master’s degree in the same at Georgia Tech, and a stint at Goldman Sachs before taking his math and programming skills to a Ph.D. in economics at the University of Minnesota. “It felt like economics had the language to ask and answer big questions I cared about around development, growth, and inequality,” Kondo said.

In 2020, Kondo joined the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute as a senior research economist and was immediately handed a major project: Coordinate with the U.S. Census Bureau to build and launch the massive public resource now known as Income Distributions and Dynamics in America (IDDA), to which we are devoting much of this issue.

The statistics in IDDA tell America’s own story of the power of institutions, the long reach of history, and people striving to escape the patterns of the past. We talked with Kondo about what IDDA can bring to the American conversation about inequality and about his own unfolding journey through America and economics.

You say that IDDA “flips the script” on how economic research often comes together. What do you mean by that?

The normal process is that I have a working paper, it gets widely circulated and potentially picked up by a journal—and then there will be a public conversation about it. It’s like a victory lap. And usually there is also some exclusivity around the data. The data’s unique nature is leveraged first by those who put it together.

On some questions, that’s good. But on some, that’s a disservice. I think of it as an underprovision of public goods in economics because of how our publication process works.

With IDDA we flip the script, in my opinion, because we’ve chosen in our partnership with the Census Bureau to maximize access for others—to not view it as a competition between what we can milk out of the data and what others could. The project is answering our research questions, but at the same time we have produced a resource that others can use to answer even more questions alongside us.

You’re a trained macroeconomist. How does it feel to put data out there in the world without having to construct an impressive, super-mathy model?

I had to be wrangled into doing it that way! My inclination by training is, Hey, you need a model, you need structure. But a model, by design, will catch some things from the data and leave some things out, and that lens is not the only lens. I’ve come to appreciate the breadth of dimensions we have in IDDA, and that one need not put one model structure on it before letting the data out. It’s exciting to see what we and others can do with it, all together, whether it’s teachers or policymakers or people using it for their research.

Have you had any initial revelations or “aha” moments yourself while working with the data?

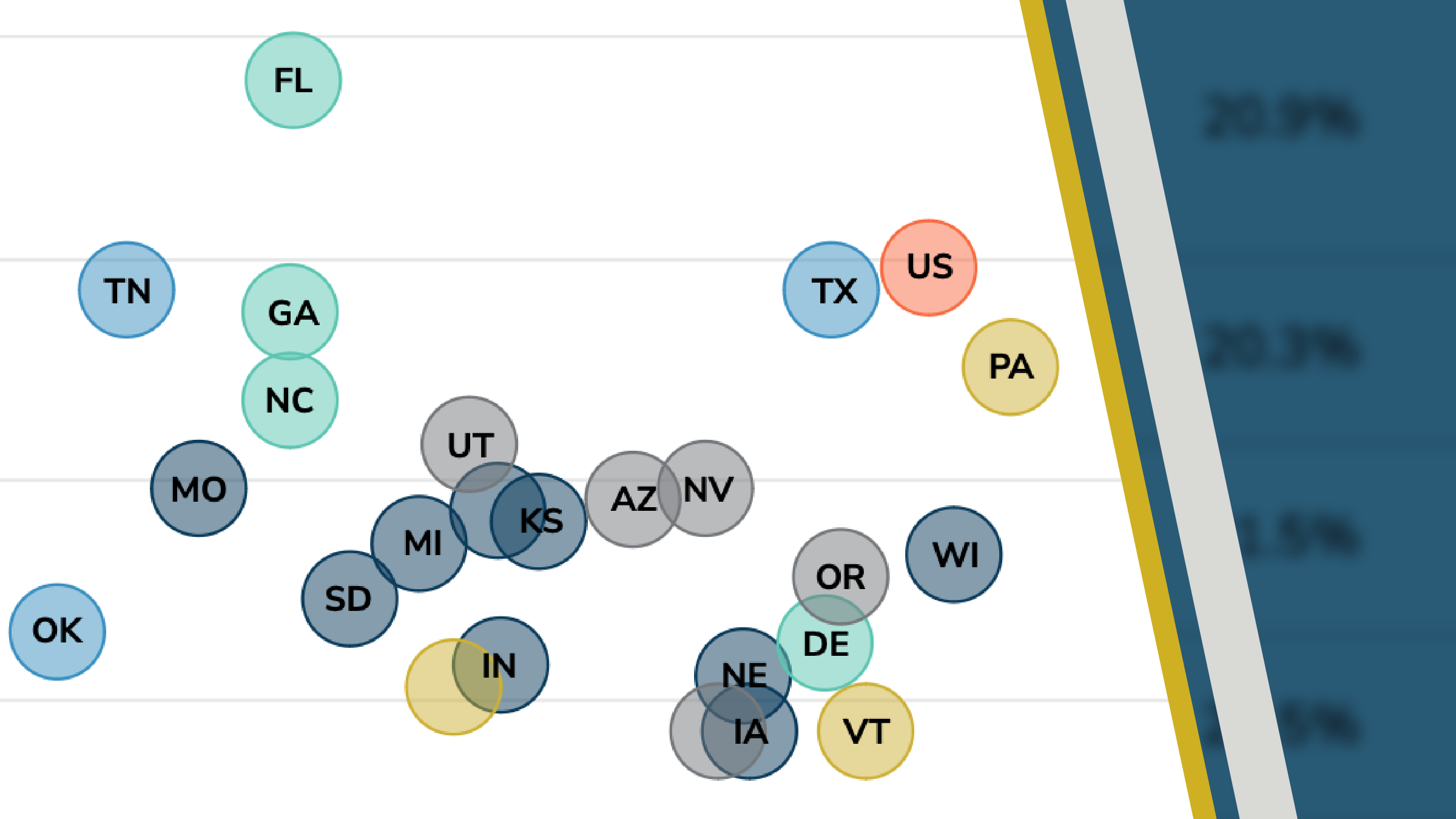

One aspect is that it’s amazing how “fractal” inequality is. Here is what I mean by that: Because IDDA is granular, you can look at, say, earnings for Black people ages 35 to 44, or you can look at Black women in Minnesota, and so on. When you look within each one of those potential combinations of place and gender and race and age, you can see: How unequal are the earnings?

In general, something like one-third of total income goes to the top 10 percent of people. And that is relatively consistent within different subgroups, which is why I call it almost “fractal.” Hispanic women in Florida, Black men in Alabama, American Indians in Oklahoma, White men in Iowa—there are some outliers, but typically there is a narrow band for how concentrated incomes are, and they are super similar.

I wasn’t expecting that. This tells you that there’s an order of things within groups that seems similar from group to group. To me, this makes more puzzling the fact that we have big differences across those groups.

Another thing that was striking to me arises because we can see very far into the upper tail of the distribution. Women earn less than men, so obviously when you go further up in incomes, you’ll see fewer women. If I look at people with annual incomes above $200,000 or $1 million, on average I would expect the women in this group would be earning less than the men—both because there should be fewer of them and because their earnings are lagging behind systematically.

But the IDDA data suggest that they don’t lag that much. There are fewer women at those top income levels, but those women seem to be on a more equal footing than I would have expected. This requires a little bit of something else to be happening, and I haven’t figured out the math for this yet. But to me this is very interesting.

You operate in an academic sphere where it is natural to talk about income disparities and inequality of opportunity. What’s your sense of how the American public views these conversations? I feel like this is a conversation that some very much want to engage in. Others are less eager.

Yes, and the data back you up. I was at a data science conference recently where researchers from Wesleyan and the University of Minnesota presented a survey about people’s perceptions of COVID-related mortality—the disparate effects of the pandemic by income and by race. And the data was just staggering. It was super polarized politically. There are big differences across political groups in how aware they were of the disparate effects of COVID.

Ivy Onyeador at Northwestern has done really cool work with her co-authors on the subjective perception of racial inequality. Essentially, we systematically underestimate how big the gaps are. And when we are told that we are underestimating, the way we rationalize it is that we say, “Well, the past was bad,” but we are super optimistic about today. We still want to think that today is good.

I think these topics are polarizing because they speak to the idea of America. Whichever way we understand opportunity or mobility or the American dream affects ultimately how we view the data in time, in space, across generations. If you believe enough in the idea, then it’s hard to deal with the data.

I think that we all want to believe in the idea. But the data is the data. What would be good is for each cluster, if you will—Republican and Democrat, former manufacturing town and booming Silicon Valley town, immigrant and nonimmigrant—to wrestle with what it means when these numbers look this way.

You shared your thoughts with the Star Tribune when former Institute advisor Bill Spriggs passed away last year. Tell me about your interactions with him and what he represented to you.

I identify as a Black economist, but I’m careful not to identify as an African American economist out of respect for people like Bill Spriggs and others who came before him. There’s work that he and others have done institutionally to create space for minority communities in economics that have not traditionally been centered there, and he did it consistently.

Getting the chance to know him and to hear his voice—especially when George Floyd was murdered and everybody was interested in his perspective on how we as economists approach the question of race—I view it as a privilege. I hold him and others of his generation in a place of both esteem and honor. But I also acknowledge that for all the work, and all that he means, I think he was marginalized by the economics community.

I helped organize the National Economic Association’s “Freedom and Justice” conference last summer where we were hoping he would come, but he passed away. And so we asked [University of Minnesota economist] Samuel Myers to give a lecture in his honor. Sam pointed out, of course, how much of Bill’s work was really influential. For example, Bill thought about things as simple as how, underneath test scores, we put the heavier weight on components of the test where White people are doing better, systematically making Black people look weak on that test.

But Sam Myers also pointed out how Bill’s Ph.D. dissertation—which was on racial wealth disparities—has never been published. This is a Black economist who was doing research on racial disparities at a top university, under a top advisor—and his thesis has never been published. The average researcher who’s going to jump into this topic today is probably not going to see what this man wrote about it.

Bill was fighting to make sure that the stories we tell as economists really work for all and are reflective of as many experiences as possible. In particular, when it comes to America, understanding that race comes with a lot and that we need to grapple with that. It was a joy to know him briefly. It was inspiring. I keep his open letter after George Floyd [“Is now a teachable moment for economists?”] near my desk, and I read it all the time.

How does your own global journey inform the way you look at inequality in the U.S.?

I think my journey has helped me appreciate the nuance around labels—in my case, that “Black in America,” “Black in France,” and “Black in Togo” mean different things. When you see a label like “Black” in economic research, people can be quick to take that as a shorthand. But my experience helps me understand that these labels are encoding more history and institutions than you think. We need to think hard about what’s behind the label, and what is really causing or explaining what we observe.

I have learned what it means to be Black as a journey across these countries. I wasn’t really conscious of Blackness as a predictor where I grew up. Actually, it turns out there is an advantage to being non-Black even on the [African] continent, but it wasn’t necessarily the biggest marker of differences as I grew up.

Then I went to France and saw the experience of other Black immigrants in France, and how France itself wrestles with the notion of race. I had to understand that history, and what it means to have a country that had to rebuild from World War II—to have a generation of people come from all over the French “empire” to help rebuild the country—only to be considered second-class citizens. These kids know nothing but France, but they are still considered a little foreign.

And what was my place in that? In France I went to one of the best engineering schools. There were a handful of us that were Black, but most of us had attended high school in Africa. And to me that was glaring. How come we were so close to a densely populated, working-class area in France, but the Black and Brown kids there could never dream of going to this amazing engineering school that was nearby?

And how about your experience being Black in America?

Coming to America was a whole other experience. When you speak to African Americans, they will explain to you how understanding the economic outcomes for Black people requires understanding the story of enslavement. If you go to a top econ Ph.D. program today, they will do the heaviest math possible. But they will probably not spend two hours understanding what the history of slavery means.

These economists are going to be writing a lot of papers talking about economic disparities, and race is always going to be one of them. The math is a requirement to get into that academic world. But understanding something as simple as an institution of enslavement is not.

I am still on that journey of understanding what it means to be Black in America. Now I have a son who, though he’s very smart, I have had to change schools for him twice—because of his color, that seems to be affecting how he’s experiencing things. As a father, I have African American kids. And I’m seeing the experiences they have, and things I have to worry about with them that I realize some of my colleagues and friends don’t have to worry about.

For me, it means when my father-in-law needed something the other night at 11:00 p.m. here in the Twin Cities, my wife is like, “Do you really need to be out driving?” It’s something she might not be worried about if she didn’t worry about what an interaction between me and a police officer would be like.

I’m not suggesting there are not other dimensions and layers we all carry. But race comes with this weight of, for better or worse, the knowledge of how you appear in the eyes of others, the knowledge of what it means in the data, and the knowledge of your own authentic experience. It’s harder for me when I think about my kids than for myself, because in a way I feel like I grew up not experiencing those things very young. But when your kid experiences those things super young, that hurts more.

When I say I don’t identify as African American, it’s a way of acknowledging that I have privileges due to my journey of immigration that others don’t. It would be really disrespectful to those who have taken the time to study the Black experience in America. At the same time, I need to take responsibility for what sometimes my presence in some rooms means and doesn’t mean.

On that point, do you have a particular example in mind?

This past week we had some high schoolers visit the Minneapolis Fed. Most of them were Black and Brown kids from a local high school. Talking to them, I mentioned how I was a little bit of a nerd, and that I love computer programming. And there’s this very tall 16- or 17-year-old, 6-foot-2, with [dread]locks. He comes up to me, says his name, shakes my hand, and he’s like, “Yeah, I do a little bit of programming. Just basic things. I taught myself Python, C, C++.”

I’m looking at this kid, he’s doing all those things, and he calls it “basic.” What I liked is that because I put myself out there saying, “Actually, I’m a little bit of a nerd,” he came to me in this humble way and we could chat about it. I’m sure he talks to other peers about programming, but from my personal experience, I knew it mattered that he felt we could chat. I told him about my friends who work for Google and other programmers I know, and I told him about Morehouse and Georgia Tech—how they train a lot of Black engineers and coders.

It’s actually the same way I feel about my daughter—the same way we want to empower daughters to be free from gender norms. When the data is so glaring in terms of a divide, representation matters. Being in the room matters.

How does “being in the room” matter as an economist?

We’re in a field that often talks about pipeline issues. The common excuse we’ll hear for not having enough women or enough Blacks in a department is, “Oh, we didn’t have enough of a good pool of applicants.” So, when I show up, I’m showing up as either one additional statistical point to reinforce your stereotypes, whether valid or not—or, hopefully, I will dispel the myth. That’s a burden that I think a lot of underrepresented groups face.

There’s this expression that nobody wants to be a token. What that means is being conscious that my presence is authentic to who I am, the quality of the work I do—but that this does not absolve our institutions from the work they have to do. I hope that wherever I am, that it’s creating more opportunities for people like me, not fewer.

I can be lovingly candid with my alma mater, the econ department at the University of Minnesota, just as I’m chatting with you about it. Yes, the small number of Black Ph.D. graduates in recent years have had outstanding job placements. But statistically, if the average Ph.D. cohort is about 20 students each year, over 10 years that’s 200 students. How come we regularly see no Black graduates from many top Ph.D. programs?

That’s the sense in which successful examples cannot be absolving. I think hard about that. For me, I think that means mentoring. That means taking on that extra service work. That means representation. Not because it builds my research— that time I spent with the high schoolers, I could have spent working on a research paper. But that’s the burden, in a way, of being in a world where we still have these glaring divides.

You have devoted a huge portion of your recent professional life to making IDDA happen. What are you excited to work on now that IDDA has launched? I noticed you’ve got a lot of work in progress related to China.

When I came to the Bank, I started working on racial wealth disparities, and the more I have looked into it, the more interested I have become. We talk a lot about incomes, and if people earn less, all else equal, they’re going to be less wealthy. But I’ve been thinking hard about what else is happening to make the ways we accumulate wealth very different. Interestingly, the research tells us that a big part of why some people are more wealthy is heterogeneous returns to investments. I think maybe there’s something racialized about it that we need to better understand.

And yes, I am working on China quite a bit. There’s been a lot of recent progress on U.S. labor market power, especially relating it to the minimum wage, but I think trade reforms are a unique place to also think about that. In other research I’m thinking about domestic outsourcing, and I have dabbled a little bit into Chinese infrastructure and institutions. Maybe that’s the engineer side of me that likes networks—I need to finish a paper about China and how politicians there shape the highway system. I can’t wait to get back to that.

This article is featured in the spring 2024 issue of For All, the magazine of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute

Jeff Horwich is the senior economics writer for the Minneapolis Fed. He has been an economic journalist with public radio, commissioned examiner for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and director of policy and communications for the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. He received his master’s degree in applied economics from the University of Minnesota.