As COVID-19 peaked in the United States, school closures affected at least 55.1 million students in 124,000 U.S. schools. Parents were forced to juggle jobs and child care, making tough decisions about who would work and who would stay home with the kids. According to a 2022 Institute working paper, working moms bore the brunt of these circumstances: In the first nine months of the pandemic, while labor force participation declined for everyone, it declined more for mothers than it did for women without dependent children or for fathers.

Some 4,100 miles away from the nearest U.S. school, Ana Sofía León was paying close attention to the schools closing around her in Santiago, Chile. As cases surged, the Chilean government implemented strict lockdown policies intended to limit mobility and high social-contact activities, but the length of lockdowns and the timing of school reopenings varied from county to county depending on local circumstances. An economist at the Universidad Diego Portales, León knew that the situation would provide a compelling natural experiment to study how the availability of school affected parents’ labor supply.

So León teamed up with former Institute visiting scholar Misty Heggeness, who studies the structures and policies around households that facilitate or hinder women’s ability to enter and thrive in the labor market. Their Institute working paper, “Parenthood and Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from Chile,” goes beyond traditional labor market measures to shed light on the complex household dynamics and decision-making that impact a mother’s ability to go, stay, and succeed at work.

A pandemic policy experiment for parents

It makes sense to assume that parental labor supply will increase when schools are open and decrease when they are closed. Indeed, research shows that mothers’ presence in the labor force takes a dip every year when schools close for the summer. However, testing these assumptions is important, and good data can answer deeper questions: Who specifically is affected—moms or dads? Moms with 2-year-olds or 8-year-olds or 15-year-olds? And, how is their work behavior affected—do they go on leave? Become unemployed? Exit the labor force altogether?

In this case, good data come by way of actions taken by the Chilean government during the pandemic: lengthy lockdowns that were set every week for Chile’s 346 counties by central government authorities. The criteria the government used to lift a county’s lockdown were not made public, but they were supposed to be based on the local case rate and trajectory. Whether schools in a specific county were open or closed was a product of both the status of the county’s lockdown and the individual school’s capacity to implement health protocols. This meant the pattern of school openings and closings varied across the country and over time.

Using data from Chile’s National Employment Survey, a nationally representative data source of individuals aged 15 and older that is similar to the U.S. Current Population Survey, Heggeness and León capitalize on this cross-county variation to explore how school reopenings affected parental labor supply. The detailed data allow them to focus on adults between the ages of 25 and 55, considered “prime working age” by economists. They then compare mothers with at least one school-aged child at home to women without children at home and to fathers with school-aged children.

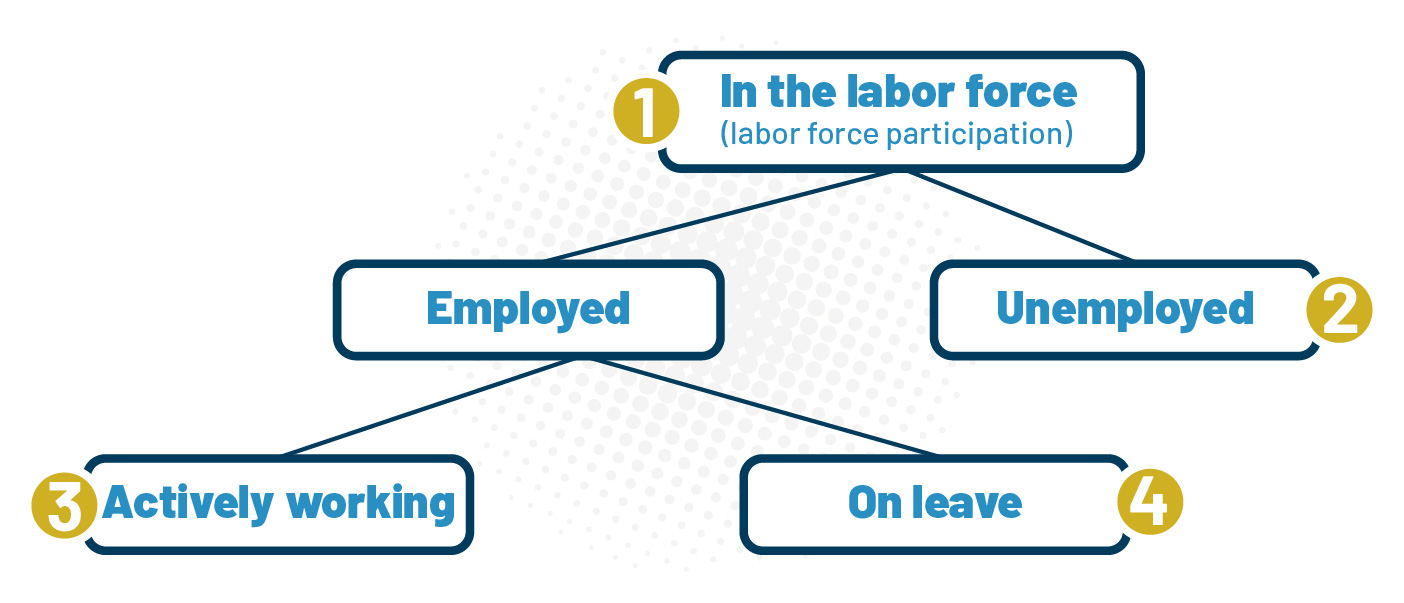

The economists purposely consider several different possible work statuses. “Traditionally in these types of research papers on labor supply, the majority are focused around the question, Are you in the labor market or not, yes or no? That’s usually where it ends. And really that’s where our research begins,” Heggeness said. “Conditional on being in the labor market, are you actually sitting at your desk doing your work? Or are you on some type of leave? The leave aspect becomes really, really important for women because there is still a traditional tendency for women to pick up the slack around unexpected and unanticipated child care needs.” The diagram shows the four work outcomes that Heggeness and León study.

Drilling down to figure out who is “picking up the slack” has implications not only for a person’s earnings at that particular moment in time but also for the career trajectories of those doing the picking up. “People who experience more personal life disruptions that impact their work capacity are less likely to advance, they’re less likely to move into managerial positions,” Heggeness pointed out. “So this is a phenomenon that really does have real-life implications for people’s ability to thrive economically out in the labor market.”

Research by Michael Judiesch and Karen Lyness, for instance, found that managers who took leaves of absence received fewer promotions and raises than those who did not take leave. Sari Pekkala Kerr identified leave-taking as a factor contributing to the gender wage gap. And other research has found a strong connection between working more hours now and wage increases years in the future.

Returning to the labor force

Twelve years after Anne-Marie Slaughter wrote the words, many mothers still feel they face “unresolvable tensions between family and career.” During the early stages of the pandemic when schools closed, mothers in both the United States and Chile increased their hours of child care and decreased their hours at paid work more than other adults.

And when schools finally reopened, mothers were the ones who were particularly affected. Heggeness and León found that the labor force participation of mothers with school-aged kids increased relative to women with no dependent children and relative to fathers. With children cared for at school, mothers who had stepped away from work to look after children could step back in.

However, being in the labor force is not the same as actively working. After schools reopened, mothers also saw larger increases in unemployment, and they were more likely to be on leave than women without dependent children at home, the economists found. As children got sick or had to quarantine, mothers once again picked up the slack.

Not only returning, but staying—with the help of older siblings

There’s less need for a parent to miss work if an older sibling can look after younger kids who have to stay home from school temporarily. Prior research has shown that older siblings, particularly older sisters, allow mothers to stay more connected to the labor market because the child care component is at least partially covered.

Heggeness and León find this pattern continued to hold during the pandemic: Mothers with teenagers were more likely to join the labor force when schools reopened than mothers with children ages 5 to 12 (and no teenager) were. “It doesn’t matter if the older sibling is a boy or a girl, it’s just the fact that there’s an older sibling there who’s able to provide some type of supervision of the younger children that allows the mother to go back to work,” Heggeness said.

But the bigger effect was not on labor force participation—it was on active work status. Among mothers in the labor force, those with a teenager in the house were more likely to be actively working and less likely to be on leave. These results show the significant impact that teenagers can play as care providers, particularly when circumstances are unstable and unpredictable.

Not only returning and staying, but advancing

On a broader level, Heggeness and León’s results highlight the sensitivity of mothers’ ability to succeed and advance at work given the disproportionate burden of domestic chores and child care at home. This has implications for policymakers and stakeholders to consider going forward.

“When thinking about a policy, you have to consider the entire decision-making process at the household level and not just look at the outcome. If you want to improve labor participation, you have to look at the dynamics within the household,” said León. “And for instance, providing child care is, I think, the minimum policy. Yet we must aim for women to not only participate in the labor force but to thrive in their careers.”

While the data that Heggeness and León analyze are specific to Chile, the results are meaningful to other countries where affordable, accessible child care is insufficient.

“Our study does have ripple effects, really across the globe, because when you think about the economic lives of women, they’re much more similar—no matter what country you live in—than dissimilar,” Heggeness said. “All mothers face these issues—the fact that we are expected to be primary caregivers within our home, generally.” Indeed, similar research analyzing the reopening of schools in Canada and the United States following COVID closures found that mothers’ employment increased more than that of other groups.

The evidence is mounting that in many places, mothers’ labor force attachment is often fragile, subject to interruption from crises far less acute than a global pandemic. Flexible work arrangements, backup care options, more evenly shared child care responsibilities, and workplaces that normalize taking leave may all have a role to play to promote women’s labor force participation and career trajectories in the long term.

Lisa Camner McKay is a senior writer with the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute at the Minneapolis Fed. In this role, she creates content for diverse audiences in support of the Institute’s policy and research work.