At farm rallies, across coffee tables and during legislative hearings, impassioned speeches are being made daily about the plight of today's farmers. But while the problem of falling farm income is obvious, finding long-term solutions is much less clear.

"It's not a new problem. We've always had income problems in agriculture," said Bruce Jones, director of the Center for Dairy Profitability in Madison, Wis.

Government has usually been there to soften the blow, even today when many claim the safety net has been pulled out from beneath farmers. In 1998, for example, some farmers in southwestern Minnesota saw total government aid more than double to $30,000.

Farmers are at once appreciative and begrudging of government support. Most farmers are very independent and want to "stay out of government pockets," said Don Peterson, president of a feed grain manufacturer and distributor in Yankton, S.D., and former state legislator for 10 years. "They don't like going to the FSA [Farm Service Agency] to see if they can go to the bathroom or to breakfast."

Nonetheless, farmers and farm advocates have been demanding government intervention in light of basement-low commodity prices, and turning the Freedom to Farm Act of 1996 into a farm crisis pinata.

The idea behind the landmark law was to give farmers more production flexibility but also more risk for production decisions. It eliminated commodity price support programs, replacing them with fixed payments that would gradually be phased out over seven years. When prices plunged in 1997, farmers were without a tangible income safety net.

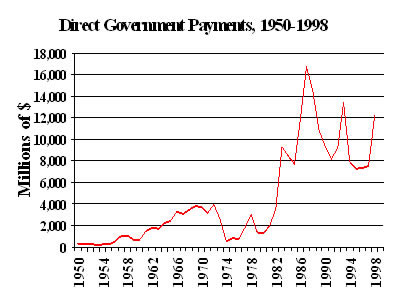

But as it has done in the past, Uncle Sam has responded to the most recent downturn in the farm economy by doling out billions in emergency aid to farmers. This year, one-third of all net farm income came from the government. If Congress passes the emergency aid proposal currently on the table (as of press time), direct government payments to farmers will approximately triple to $21 billion this year-about $4 billion more than the farm aid record set in 1987.

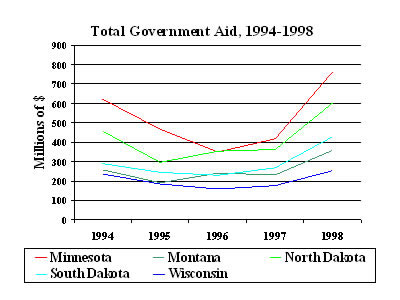

Much of that aid has found its way to states in the Ninth Federal Reserve District. In 1996-for many the last "good" year in farming-total aid to Wisconsin, Minnesota, the Dakotas and Montana was $1.4 billion. By 1998, that figure had jumped 70 percent to $2.4 billion.

"Congress is out there spending a pot full of money, and I don't think they have a good handle on where it's going," said Tracy Beckman, director of the FSA.

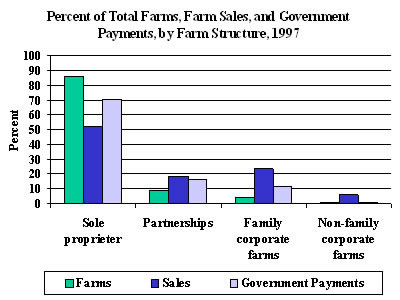

Critics of current farm policy point out that most aid goes to large farms because government payments are based on past production rather than targeted to individual farmsteads. For instance, the bottom two-thirds of all farms receive just 12 percent of all government payments. But the equity argument can be spun the other way as well. These farms have annual sales under $20,000, and include many part-time, hobby and retirement farms, whose household income comes mostly from off-farm sources. Collectively these farms produce only 6 percent of all farm output, which means they currently receive about twice the amount they would receive under a proportional production formula.

Farm advocates also argue that aid does not reach the most troubled farms. This is true as well, but overlooks the marginal utility of such aid, where aid goes to bolster sagging farm income for less vulnerable farms, rather than used to save farms falling headlong into bankruptcy or foreclosure. Even so, one government report said vulnerable farms—those with high debt and low or negative income—receive about 5 percent of total government payouts, which was "roughly equal to their total contribution to commodity sales."

Don't fence my subsidies in

The issue of "subsidy equity" among farmers is complicated. On the surface, it sounds like almost all farmers are complaining about poor prices, the demolition of the government safety net, and the need for government to "do something."

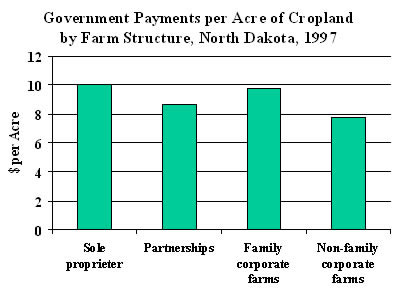

That's not likely the case, because not all farmers receive much, if any, government aid. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), a little more than one in three farmers receives any direct money from Uncle Sam—the result of the government's bias for subsidizing only a handful of crops. But such a bias favors Ninth District farmers, where well over half of all farmers received government aid in 1997, according to the USDA's five-year farm census. In North Dakota, four of five farmers received aid.

Pre-1996 federal farm policy focused on commodity price support programs, whereby government aid would kick in when prices for wheat, feed grain (mostly corn, but also oats, barley and grain sorghum), rice, cotton and wool dipped below a certain level. Such policy largely ignored the other 70 percent of farm product sales, which include all livestock, dairy, fruits, vegetables and nuts.

Among subsidized crops, most direct government aid goes to corn and wheat growers because of their production volume. In 1995, the last year of the old farm policy, corn and wheat took home three-quarters of $4.5 billion in price support subsidies, with rice taking home 17 percent, and others picking up subsidy crumbs.

The Freedom to Farm Act did little to change which crops receive government subsidies. Under the new rules, fixed payments (called production flexibility contracts, or PFCs) go only to those farmers eligible in the past for price supports-namely feed grain, et al. So while current prices for many crops and livestock are low, not all farmers receive assistance under the new law, just as they didn't under the old law.

Even so-called farm bailout packages favor major row crops because they are usually patterned after existing subsidy programs. In October 1998, Congress passed $6 billion in emergency aid to farmers. Roughly $3 billion was slotted for market loss assistance (MLA), which went only to farmers eligible for production flexibility payments (again, mostly growers of feed grain, wheat and rice). The remaining $3 billion or so went for disaster relief, which covered all farmers who experienced significant crop losses, including major crop commodities. Only about 3 percent was allocated specifically for "secondary" crops or livestock, according to one USDA source.

The current $8 billion-plus aid package in Congress would be more of the same, with roughly two-thirds being used to double aid to those farmers receiving PFC payments. Remaining money is sprinkled among oilseeds, specialty crops, cotton, tobacco, livestock, dairy and improved crop insurance discounts.

Such a bias for major commodity crops has a dramatic impact on where farm aid flows, even among the five ag states in the Ninth District. For example, four years of flexibility payments plus 1998 MLA payments have brought $1.4 billion to Minnesota farmers. In contrast, North Dakota farmers, who number fewer than half their eastern neighbor, received more than $1.1 billion. Wisconsin farmers, roughly equal in number to their Minnesota peers, received $520 million.

Ninth District farmers also take home hundreds of millions from other government programs. The loan deficiency program (LDP) lends money to farmers based on their crop volume, allowing them to hold a crop for up to nine months in hopes of getting a better price down the road. Once again, LDP benefits mostly major row crops (including soybeans in this case). Nationwide, more than 80 percent of $1.8 billion in loan deficiency payments made in 1998 went to producers of wheat, corn and soybeans. The USDA projected this year's LDP payments will more than triple due to low prices for these commodities.

Owners of land previously used to grow feed grain and wheat in the Ninth District also take home most of the $400 million received annually from the federal Conservation Reserve Program, which pays farmers annual rent for taking environmentally sensitive land out of production for 10 to 15 years.

Not all farmers are banging on the subsidy door for their fair share, however. Livestock ranchers have historically resisted the lure of falling back on government aid during tough times. Cattle ranchers were wary when hog farmers sought federal and state assistance last year to combat Depression-era prices, according to Michael Held, administrative director of the South Dakota Farm Bureau. "Once they take that bait, they're going to be on the hook," Held said.

How now, brown cow?

While few people are happy with existing U.S. farm policy, there is very little consensus on what government should do to help farmers, and what policies would help farmers remain viable and competitive in global markets. But amid the current stress, most farmers are saying they do not want to go back to the old farm policy.

"I don't hear anyone that wants to eliminate Freedom to Farm," Peterson said.

"We are not ready to go back to government controlling supply," said Held. "[Farmers] would rather we improve from where we are than go back to supply management programs."

But the current crisis also presents a new problem for farmers, according to Rob Hamer, director of Minnesota Farm Credit Mediation. In the past, when a farmer got into trouble, "you look back to the way before, which always gave you a way out." With the new market-oriented approach, "you can't look at history and say how to get out" of the current tailspin, he said.

Robert Carlson, president of the North Dakota Farmers Union, said there needs to be more than two options for farm policy—the current program or the previous program. Past supply—control programs are not relevant in a global farm market, Carlson said, adding that today's "trade war" with farmers worldwide demanded new export levers to help U.S. farmers fight for market share.

That means abolishing the food-based foreign policy, Held said. Such policy "constantly shoots farmers in the foot," he said, as embargoed commodities are easily filled by other countries, surrendering export market share with little fight or net benefit. He pointed to the 40-year embargo on Cuba. "What have we gained?" Held asked.

Clouding federal policy today are potentially cross-cutting goals of ensuring a stable food supply and stopping the hemorrhage of farmers going under. On the surface these goals might seem consistent and mutually desirable. But increases in domestic and world farm productivity have risen faster than demand, which means the food supply can be produced by fewer farmers and ranchers. As a result, a "relentless" market eventually forces some of the excess production out of farming, said Jones of the Center for Dairy Profitability.

"We're never going to keep farmers from going out of business," Jones said.

But trying to align supply (farmers and farm output) more closely with demand has significant risks, several sources pointed out. "You certainly don't want to try to put [supply] right at the edge [of demand]," said Dale Thorenson, a North Dakota farmer. "Grain doesn't appear out of thin air."

Unpredictable weather and other production factors can wreak havoc on crop production. "It isn't like making toasters, where [you] can just flip off the assembly line," Carlson said. "What happens if the [food] surplus goes away?"

Many, in fact, believe that subsidizing small farmers has social as well as economic value. They point to the European Union model, where the agriculture industry receives (depending on farm conditions) about two to 10 times the amount of subsidy of its American counterpart.

"The sole [U.S. farm policy] focus is economics," said Beckman of the Minnesota FSA. "Most of the rest of the world sees farms as an issue of national security," But despite the supposed market orientation for farmers, Americans have not been able to stomach the fallout when times turn bad for farmers, and Congress inevitably rushes in with billions in emergency aid.

"That's a strong contradiction," Beckman said. "Why not just subsidize the small farmer?"

"If this was just about saving a handful of us in small communities, it probably wouldn't be worth it," Thorenson said. The real issue, he said, is the preservation of a decentralized food production system and the rural communities that depend on the farm sector.

Jones said such a policy might lie ahead, but is not without consequences. "There may be a time when we decide that we need to" support farms for social infrastructure reasons, Jones said. "We can try to keep all farmers, but history tells us that can be a very expensive proposition."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.