This time of year, rural areas are filled with the machine-heavy sounds and smells of harvested crops-combines gobbling ripened wheat, and freshly shelled corn wafting its way to elevators and storage bins.

But the normally sweaty-but-satisfied mood on the farm at harvest time has turned dour. Farmers are reaping a bumper crop of anxiety over poor crop and livestock prices and significant weather-related crop losses in Montana, North Dakota and Minnesota. Despite good crops throughout much of the Ninth Federal Reserve District, harvests are taking a back seat to community rallies, congressional posturing and strong rhetoric about the crisis facing today's farmers and the dismantling of the farm safety net three years ago with the Freedom to Farm Act.

To many, the situation has hit a crisis stage. The Minnesota Farm Service Agency (FSA) said 6,500 farmers "may likely" go out of business in the next year if farm conditions don't change. Farm advocates are calling for intervention to help farmers make ends meet, comparing the current situation to the crisis of the early 1980s. A search of the top 50 U.S. newspapers in the last two years found a proportional number of "farm crisis" stories compared with five-year stretch starting in 1981.

But where, exactly, is the current farm crisis hitting home the hardest? Scraping beneath the topsoil shows that not everyone is hurting, or hurting to the same extent. While the farm economy is stressed, the situation is not as dire as it was 15 years ago-at least not yet.

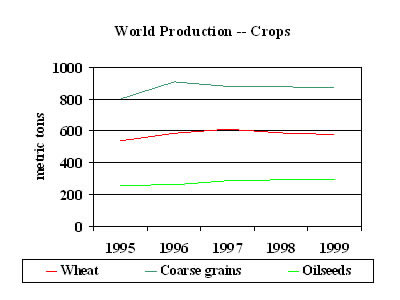

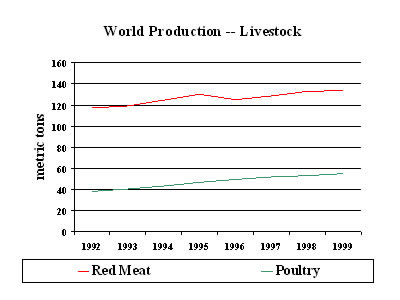

The recent downturn in the farm economy started in 1997, when robust prices for major crop commodities began to collapse. The price drop was the combined result of falling demand - much of it due to the Asian financial crisis, where exports dropped significantly - and strong domestic and world production of major crops and livestock. Combined, the two factors have produced significant worldwide surpluses, which have driven prices to rock bottom.

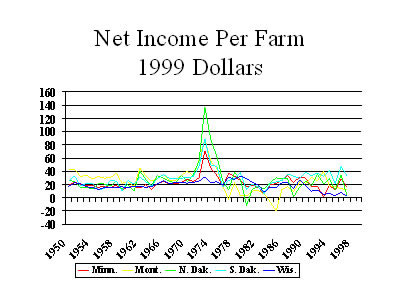

"If you can make money at these prices, you are one hell of a farmer," said Kenny Rogers, a retired farmer and now a negotiator with the North Dakota Agricultural Mediation Service. "The numbers don't work no matter how you run them." North Dakota farmers saw net income plummet by more than 90 percent from 1996 to 1997. A sample of farmers in southwestern Minnesota watched their incomes drop from an average of $55,000 in 1996 to just $8,600 last year.

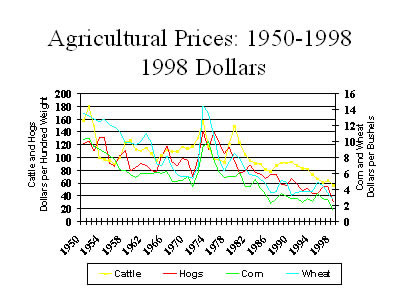

Hardest hit are commercial, or full-time, farmers, whose livelihood rests in the prices they get for crops and livestock, most of which are currently low. Prices for corn, wheat and soybeans dropped precipitously two years ago and stayed there. Cattle and hog prices have been poor throughout this decade, with hog prices dipping last year to levels not seen for 70 years.

Among major commodities, dairy farming has been the lone bright spot. Until recently, milk prices had been strong for a couple of years, and somewhat ironically, boosted further by low costs for feed grain.

"Besides dairy, everything else is in the tank," said Roger Cliff, executive director for government relations with the Wisconsin Farm Bureau. A recent 25 percent decline in milk prices promises to bring dairy farmers closer to the rest of the agricultural pack.

Farmers are not the only ones hurt by low commodity prices, either. "The crisis also directly affects the farm supply businesses and cooperatives, machinery dealers, banks and credit unions with heavy ag portfolios, and virtually all businesses in communities dependent upon farmers' and ranchers' income," said Robert Carlson, president of the North Dakota Farmers Union.

Is this the 1990s version of the 1980s crisis?

Farm advocates have used declining farm income, local upticks in foreclosures and mediations, and slumping sales at farm supply businesses as evidence that the farm economy is in a full-blown crisis like that of the 1980s. Headlines were made when 30 foreclosures occurred in North Dakota in the first six months of 1999, double the usual amount since 1992. Farm mediations are on the rise, as are anecdotes about farm auctions.

A look at financial data and historical trends, however, paints a different picture-one that says we might be heading in that direction, but are definitely not there yet.

Today's farmers and farm banks reportedly are more cautious about their borrowing and lending habits than in years past. Farmers are wondering if and when to get out "before they lose too much of their equity," Cliff said, whereas falling land prices literally forced farmers off their land in the 1980s. As a result, farmers are collectively in a better financial position today compared with the last farm crisis. Last year, loan payments consumed 14 percent of farmers' gross cash income, just half the level paid in 1983.

"From a balance sheet, things still look pretty good," said Cliff, who quickly added that would change if prices don't bounce back, as farm income can fall short of expenses for only so long.

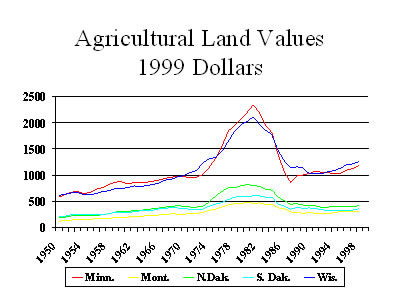

There are some similarities between today's farm situation and the 1980s crisis. Overall farm debt has risen steadily in the 1990s, and is at its highest point since the 1980s farm crisis. Then as now, tight world food supplies led to optimism and good prices, both of which vanished shortly thereafter. Land prices today have been rising—albeit more slowly—just as they did prior to the last farm recession. From 1993 to 1998, Wisconsin farmland values rose 56 percent. Last year, South Dakota farmland rose by 2 percent, and Minnesota's increased almost 8 percent.

Such increases soften the "paper outlook" as a farmer's assets and equity grow somewhat irrespective of farm profitability. If land prices were to drop suddenly like they did in the mid-1980s, the outlook would be significantly worse, leaving farmers with fewer assets to leverage for operating loans, possibly even owing more than the farm is worth.

But similarities aside, the current crisis is much different from the 1980s crisis, when high debt and interest rates squeezed many farmers too tight. According to one expert testifying at a recent USDA Emergency Board meeting in Minnesota, farmers were staring at interest rates of 15 to 17 percent in the 1980s, whereas farmers today are getting loans at 8 to 10 percent. The nation's economy is also more stable than it was 15 years ago, thanks to lower unemployment, strong job growth, wage increases and government surpluses at the state and federal levels.

Debt = doom

Most sources generally agreed that indebted farmers would have the toughest time dealing with low prices, as lower farm receipts will make it virtually impossible to cash-flow their operations while paying off existing debt.

"For those in grain farming, if they have debt, they're in a world of hurt," said Dale Thorenson, a North Dakota wheat farmer who watched much of his 3,400-acre farm go unplanted this summer due to spring flooding.

Unless decent-paying work outside the farm can be found, Rogers said the older farmer with steep loans on capital intensive farms "is almost forced to continue until he either goes broke or he can retire."

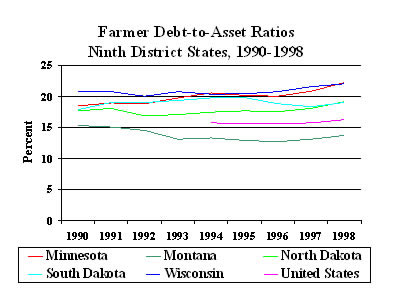

Debt is rising for farmers, but was still $22 billion below the peak of $194 billion hit in 1984, and further mitigated by farm assets that grew faster than farm debt this decade. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) considers a debt-to-asset ratio of 40 percent to be the financial line in the sand for farmers. By that measure, the vast majority of farmers have a good short-term outlook, according to the most comprehensive government data available. The USDA reported that more than half of all farmers typically have no carry-over debt (a debt/asset ratio of zero), and nine of 10 farmers reported ratios under 40 percent in 1997. Farmers in the five-state area appear to be in a little tighter spot. With the exception of Montana, whose farmers have a debt-to-asset ratio of just 14 percent, Wisconsin, Minnesota and the Dakotas all have debt ratios that are one to six points higher than the national average of about 16 percent.

Anecdotes about bankruptcies and foreclosures are in ample supply, but through 1998 commercial lender groups had "historically low" levels of delinquencies, foreclosures, net loan charge-offs and loan restructuring, according to the USDA.

In 1988, for example, there were about 140,000 active delinquent farm loans owing $11 billion to the Farm Service Agency (FSA), which holds a majority of high-risk farm loans and guarantees loans made by commercials banks. Over the next 10 years, delinquent FSA accounts dropped by 80 percent to just 28,000, who owed just $2.3 billion. The Farm Credit System also saw its delinquency portfolio drop by 80 percent during the same time period.

The Minnesota FSA reported that its delinquency caseload through August of this year dropped by 20 percent over the last six years, and delinquency rates among active loans have remained steady.

The sky IS falling?

Because data gathering on farm conditions typically lags behind the farm business cycle, government statistics often don't show the short-term volatility of farming operations. For that reason, some believe things have changed dramatically in just the last few months.

Based on an informal survey by its 81 district offices, the Minnesota FSA recently predicted the state will lose 6,500 farmers in the next year if farm conditions did not change. State Director Tracy Beckman called the survey "subjective as all get-out," yet the figure immediately entered the public lexicon as fact despite being considerably higher than any single year in the 1980s, when there were also more farmers to lose.

Beckman nonetheless stood firmly by the survey's conclusions. "I think [the estimate] is conservative." Farm conditions have worsened dramatically in the last few months, he argued, which would not show up in 1998 data.

"In our opinion, there's something different going on," Beckman said, pointing to a "major structural change" that is affecting large numbers of marginal farms that have managed to stay alive for years, oftentimes thanks to government aid. Emergency aid passed last year helped some farmers hang on, Beckman said, but only temporarily.

"All that [farm aid in 1998] did was hold this down," Beckman said. Overall loan activity is picking up with the FSA, he pointed out, and commercial bankers are increasingly skeptical about their farm loan portfolios (see related article on the Minneapolis Fed's survey of farm banks on page 11). The Minnesota FSA predicted an increase of 120 percent in total borrowing from 1998 to 2000, and continuing to increase to the height of the 1980s crisis.

FSA loans have increased as well in North Dakota. Scott Stofferahn, FSA executive director there, said farm loans in a typical year are about $30 million, but hit $45 million this year. He added that FSA's guaranteed loan program (which enables commercial lenders to extend credit to farm producers who do not qualify for standard commercial loans) "have nearly doubled" over last year to $134 million.

"Bankers all across the state are telling me they will be using the guarantee program more aggressively in the coming year than they have in the past," Stofferahn said, "What I gather from many of them is a level of nervousness that has not been seen for some time. Our own loan officers have told me that they don't know what kind of a rabbit they will pull out of the hat for the coming year to patch our customers' operations back together for yet another year."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.