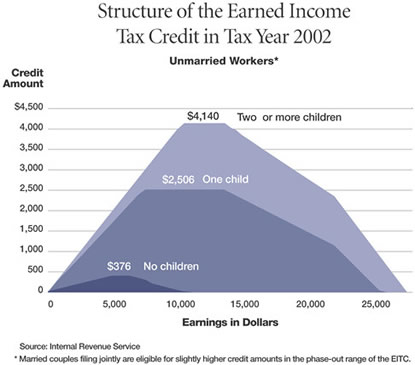

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is, in effect, a wage subsidy to low-income workers—it makes work pay, in political jargon. Enacted in 1975 on a smaller scale, the program has managed to gather bipartisan political support over time and with it, much higher financial incentives that allow it to pull more working families above the poverty threshold than almost any other social program.

Here's how it works: A single parent with one child who works 20 hours a week, year-round, at $6.25 an hour makes an annual gross income of $6,500. Come tax time, that parent can claim the EITC and receive a nice little bonus of $2,202. This "credit" typically includes a full refund of any federal payroll and income taxes paid by the worker and tacks on an additional cash grant.

But the unique part of the EITC is that it makes work pay on an upward (though limited) sliding scale; additional work not only produces higher salary earnings, but also is supplemented by still-higher EITC payments. For example, add 10 more hours per week (520 annually) to the example above, and work alone produces income of $9,750, and the EITC hits its maximum credit of $2,506, which pushes this particular household just over the poverty threshold of $12,120 for a family of two.

A second design feature of the EITC is that it is more generous to

multiple-child families—a nod to the fact that child poverty

rates grow as the number of children in a family increases. Give the

above worker two or more children, and the maximum EITC credit reaches

$4,140. Depending on family size, the EITC's maximum subsidy rate

can reach as high as 40 percent of earned income. (Much smaller credits

are also available to low-income workers with no children, maxing

out at $376 for those with incomes generally falling below $12,000.)

The EITC eventually takes away the punch bowl, cutting the credit as incomes rise to what it calls the phase-out range. For single-parent families, the EITC begins to drop once income reaches $13,550, and hits zero at about $29,000; for two-parent, multiple-child families, the phase-out starts at $14,550, and the credit lapses at about $34,000.

About one quarter of all EITC recipients live in states that also offer supplemental EITC-like programs, according to a 2003 report by the Brookings Institution. Currently, there are 15 states and two local governments (Montgomery County, Md., and Denver, Colo.) that supplement federal EITC payments. Ten states offer refundable credits like the federal version, where a worker can get back all state tax obligations plus an additional cash grant. Remaining state programs stop after wiping out a worker's state tax obligations.

Minnesota and Wisconsin have two of the most generous state programs. Minnesota's credit ranges from 25 percent to 45 percent (with a statewide average of 29 percent) of the federal credit, depending on family size and income. Wisconsin's credit ranges from 4 percent (one child) to 43 percent (three or more children) of the federal EITC. At the upper end for both states, some recipients can see an additional refund of more than $1,000.

Return to: Anti-Poverty Design: The Cash-Out Option

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.