Few themes were as prominent in this past election as jobs. Indeed, since the recession that began in March 2001, jobs have been the subject of much attention, confusion and disagreement.

Much of the political controversy and general befuddlement stems from the fact that it has taken longer for the nation's job base to spring back to life than after any recession in the last 50 years. Add to that the angst over job outsourcing to low-wage countries and a growing perception of the United States as a nation of burger flippers, and you've got yourself a perfect subject for discussion at the annual retreat of the Minneapolis Fed's board of directors, held in late September.

President Gary Stern told directors the topic of jobs "was the obvious choice" for this year's retreat. "For quite some time, there has been a lot of concern about the so-called jobless recovery." He pointed out that the phenomenon of a jobless recovery first gained notice in the 1991 recession, when it took roughly 18 months for job growth to gain solid traction, and about 30 months to reach prerecession peak employment.

"Compare that to the current episode," Stern said, where "it took about 33 or 34 months for employment to start to pick up noticeably, and it still hasn't surpassed its prerecession peak. I think that depicts the origins of this conference."

The retreat, titled "Jobs in the U.S. Economy: Composition, Creation and Destruction," was designed to give directors an inside look at how job data are calculated, and some of the shortcomings of those data; the dynamics of the U.S. job market; changes in labor force composition; and the effects of trade on jobs.

Mirror image, only different

Of all the controversies surrounding the jobs issue, one might think that there is at least a hard-and-fast count of jobs themselves. While there are (what people believe to be) reliable measures, the simple measurement of jobs is not so simple after all. Warren Weber, senior research officer with the Minneapolis Fed, gave directors a glimpse of the difficulties.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) uses two labor surveys to get a monthly estimate of employment. One, called the payroll (or establishment) survey, polls 400,000 work sites to get a monthly count of payroll jobs. The other, called the household survey, asks 60,000 households about their employment status.

For decades, the two surveys have mirrored each other, Weber said. But in the 1990s, their trend lines diverged more than at any other time in at least the last 50 years. The contrast is especially striking in the recession that ended in November 2001. The payroll survey-the most widely cited of the two, particularly in media reports—shows U.S. employment still lagging below its 2001 peak. The household survey, on the other hand, shows that jobs rebounded much more quickly, surpassing 2001 peak employment roughly 18 months ago (see Chart).

What gives? Daniel Sullivan, vice president and senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, told directors that "something weird happened in the 1990s" regarding post-recession trend lines in employment and the differences between the two BLS surveys.

One popular hypothesis for the differing results is that because the payroll survey does not count the self-employed, it undercounts total employment (possibly by a lot) as laid-off workers test their entrepreneurial skills. The household survey, in contrast, does count the self-employed.

However, Sullivan argued that much of this self-employment "is disguised unemployment." During and immediately after a recession, the number of self-employed workers naturally rises as workers do odd jobs to keep some income rolling in while they look for regular work. But in the most recent recession, the self-employment rate was significantly lower than in the previous three recessions (see Chart 2).

Research published this year by Sullivan and Chicago Fed colleagues Daniel Aaronson and Ellen Rissman* looked at rates of incorporation, which Sullivan said is a measure of staying power and commitment to a business endeavor for a self-employed person. Their study found that proportionately few self-employed workers have bothered to incorporate their business.

In the end, Sullivan said, while both surveys have their flaws, the payroll survey was likely more dependable because it is benchmarked to—and matches closely with—data on total so-called covered U.S. employment (or the number of jobs reported annually by employers as part of unemployment insurance requirements). The household survey, on the other hand, has no direct benchmark other than the decennial census; annual household adjustments are made to census figures, but they are only estimates. Stern agreed with Sullivan, noting, "If you had to put a quarter down on one or the other as being the most accurate, you'd put it down on the payroll."

And that leads back to the original—and more perplexing—problem: the notion of a jobless recovery. Sullivan showed that the phenomenon first surfaced in the 1990s. In the four recessions that occurred between the 1960s and 1980s, average job recovery was steady and virtually immediate (see Charts 3 and 4). After the recession of the early 1990s, however, total employment continued to lag well after the trough of the economic downturn—a phenomenon that has become even more elongated in the most recent recession.

The term "jobless" recovery is something of a misnomer, argued Sullivan, because it implies that no jobs are being created. "When someone says nobody's hiring, that makes me laugh," Sullivan said. Monthly net job growth "hides a lot of fluctuation" in jobs both gained and lost. In the fourth quarter of 2003, for example, the nation saw a net growth of 344,000 jobs. But this masks the fact that some 7.6 million jobs were added during this period, and 7.3 million jobs were lost. However, the difference between job recoveries of the past and present is that job creation today has not bounced back as it normally does after a recession (see Chart 5).

Estimates represented by lighter colored lines are based on R. Jason Faberman's calculations from the Business Employment Dynamics data of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. See his BLS working paper titled, "Gross Job Flows over the Past Two Business Cycles; Not all 'Recoveries' are Created Equal" for details on these calculations.

Source: Daniel Sullivan, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

Economists don't yet have a conclusive explanation for this new trend, though there are theories. Strong productivity growth, which allows employers to increase output without having to increase labor, has been widely cited as a possible reason for the jobless recovery. But Sullivan noted that employment gains typically follow productivity gains because higher productivity tends to lead to faster growth in demand. Existing workers, if truly more productive, should be getting better pay, according to Sullivan; and with higher incomes, they should be buying more.

Another explanation has to do with longer lags in the so-called sectoral reallocation process. As the economy becomes more specialized, the argument goes, recessions induce more dramatic reallocation of capital and labor among sectors of the economy. For example, workers moving today from manufacturing to health care require a longer retraining period than in past recessions, when they moved from shoemaking to, say, window production, or simply waited for demand to return so they could go back to their old job. But research by Aaronson et al.,** stemming from earlier research by Rissman, shows that, on average, reallocation of employment between sectors has actually declined, not risen, over the past two business cycles.

Sullivan said a more convincing (though not certain) explanation for the jobless recovery is just-in-time hiring with temporary services firms, consultants and other as-needed contract labor. In days past, firms had to make a choice: add workers in anticipation of increased demand and assume the risk of unnecessary labor costs if demand didn't materialize; or hold off on hiring until demand rose, but lose profit opportunities while scaling up production to meet demand.

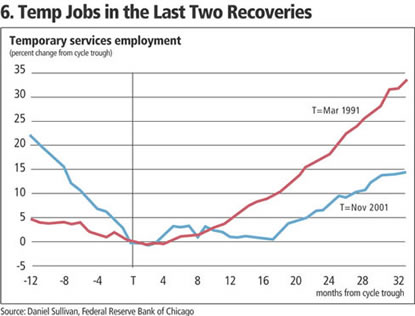

Just-in-time hiring allows firms to add help on short notice when demand increases without assuming the financial risk of adding full-time workers. But it's exactly this possibility, the Chicago Fed researchers write, that "restrains hiring that might otherwise have taken place in anticipation of demand growth." Their research also points out that economic expansions might not coincide with immediate increases in temporary services employment (see Chart 6). But because just-in-time hiring allows employers to react much more closely to real-time increases in demand, increases in temp services employment are "likely to signal a pickup in overall hiring some time later."

Changing faces

As society experiences new economic phenomena like jobless recoveries, it's inevitable that policymakers will want to "do something" to correct perceived problems. But before they do anything, they should understand that some fundamental changes have occurred in the workforce—changes that are not visible at first glance, warned Ellen McGrattan, a monetary adviser at the Minneapolis Fed.

McGrattan indicated that most studies of business cycles and labor activity treat the labor force as a homogeneous group of workers with relatively uniform, unchanging characteristics. Intuitively, you might know that's not the case, but policy tends to ignore differences among diverse workers and changes in the makeup of labor over the last 50 years.

The aggregate labor pool from 1950 to 2000, for example, shows a small (7.2 percent) increase in the total number of hours worked per week, a small decrease (4.6 percent) in the hours worked per person and a small rise (12.3 percent) in the percentage of working-age people who are employed. Sounds pretty ho-hum, huh? But if you look more closely, "you see huge differences," McGrattan said. "There has not been a big change in the labor force, but a change in the faces of the labor force."

For example, "there has been a dramatic shift [in hours worked] from men to women" over this 50-year period, she said. Females (as a population) almost doubled their average hours per week (close to 20), while men saw a 17 percent decline to about 28 hours. Changes were also seen across all age groups for both men and women.

Splitting the labor pool further, McGrattan showed that hours worked changed little among single females, but married women saw huge increases. Single men and single women look fairly similar in their characteristics over time, while married men have, on average, given up some hours and married women have taken on more. In fact, McGrattan said, married households now have work characteristics similar to that of two single workers. At the same time, the percentage of workers who are married has dropped by better than 17 percent since 1950.

"We macroeconomists are mushing [distinct labor pools] together," McGrattan said. The differences among these labor groups are important, Gary Stern later summarized, because if you ignore them "you may miss a lot of fallout from any important policy changes that have labor market implications."

Trading jobs

Art Rolnick, senior vice president and director of Research at the Minneapolis Fed, introduced the controversial issue of international trade and jobs. From a historical standpoint, Rolnick said, "this is a debate that's been going on many, many years." In Principles of Trade, Rolnick noted, Ben Franklin wrote, "No nation was ever ruined by trade, even seemingly the most disadvantageous."

Many believe that trade leads to job loss—evident in offshoring and outsourcing practices that take businesses and jobs to low-cost countries like China. In fact, said Rolnick, the opposite is more likely true. Economic growth inevitably leads to employment growth, and since the 1930s there has been strong and steady growth in imports, exports and gross domestic product—"prima facie evidence that you can have trade and growth," Rolnick said. Another historical phenomenon in favor of trade is that "great cities were great cities because of good trade locations," which generated lots of economic activity, and therefore jobs.

V.V. Chari, a professor of economics at the University of Minnesota and an adviser to the Minneapolis Fed, told the directors that trade is a win-win scenario and could be summed up "in one word: specialization. ... Specialization is a key source of prosperity and important without [international] trade" because it applies to families, neighborhoods, cities and states. Labor specialization is what has freed people from having to grow their own food, make their own clothes "and play our own music to our families," Chari said.

Preston Miller, a Minneapolis Fed vice president, tutored directors on trade and comparative advantage, where specialization and trade among countries allow them all to produce (and therefore consume) more of the goods being traded. But Miller also pointed out that comparative advantage focuses on production and the allocation of work within a finite pool of labor, and as such does not have a direct correlation with employment trends.

Nor does this picture exactly fit the public's perception concerning trade and job security. Chari took aim at some common fears regarding trade, including one uniquely summarized by one of Chari's daughters, who proclaimed she wanted to go to China. When Chari asked why, she answered, "I want to see where they make things." The fear among adults is that cheap labor in China and other low-cost countries brings cost advantages across the board (what economists call absolute advantage), which means eventually everything will be produced somewhere else and "there will be no more jobs in America."

But Chari argued that "absolute advantage is irrelevant," and that comparative advantage determines patterns of trade because, simply, there is too much demand—too many products and services—for low-cost countries to satisfy, particularly in light of the fact that "low wages are a sign of low productivity." These fears also assume that aggregate demand (and the jobs that serve those needs) is finite and static. In contrast, Chari said, growing prosperity has shown that "our material needs appear infinite."

Trade critics also charge that large wage differences among countries will lead to an international "race to the bottom," with low-wage nations as the default winners of production and jobs. Chari turns the question back on itself: Why are wages low in some countries? "We think we have a pretty good handle on the answer," he said, summarizing the problem as "less education, less physical capital and more restrictions" to economic activity compared with higher-income nations.

Begging to differ

Louis Uchitelle, a senior economics writer at the New York Times, offered some skepticism about the claim that increased education and higher skills can offset job losses that stem from international trade or outsourcing or some other cause. He argued that the supply of workers, including educated workers, often exceeds the demand for them, and he runs into that constantly in his reporting for the Times.

"We have concluded absolutely that education and skill will lift people into work and to good pay," Uchitelle said. "My experience is that training is all well and good. But I find over and over again that the supply of people, well trained or not, is very often greater than the number of jobs available for them."

He added that economists often treat layoffs abstractly as normal job churning and they lose sight of the psychological damage that results, even for people who soon get another job. "Very few people can let [a layoff] roll off their back," he said. They tend to blame themselves for losing a job, rather than social forces beyond their control.

Not everyone agreed with Uchitelle's prognosis. Board director Jay Hoeschler, owner of a realty and development firm in La Crosse, Wis., said his hometown "has been dominated" historically by a few large manufacturing companies, all of which have undergone major upheaval. "We've experienced all these layoffs," Hoeschler said. At one point, the La Crosse-based G. Heileman Brewing Co. was the fourth largest brewery in the nation. But it later went through ownership changes and layoffs, and today is owned by a regional brewer employing a few hundred. Trane, a manufacturer of air conditioning units, laid off 350 workers about a year ago after it moved some production to Mexico and China. La Crosse Footwear, a 100-year-old shoe manufacturer, closed down all operations in the city a few years ago.

"But yet ... at least from my experience in our community, I don't see how our community is worse off for all of that. The community itself has been able to survive quite nicely," Hoeschler said. The quality of housing continues to improve, there has been no spike in poverty, and unemployment today stands at 3.2 percent.

"And on retraining, we have kind of the bright side of the story. ... From day to day, I talk to people, neighbors [who] have found other work. One individual I know is a nurse at the hospital-following what he really should have been doing in the first place. So it seems like they've gone back and gotten the retraining and found other jobs, and I don't hear a lot of complaints." There are some grumbles about pay levels, but "they must be satisfied with the jobs they have from a lifestyle standpoint, [because] I don't hear a lot of [other] complaints."

Hoeschler acknowledged that layoffs might represent some "chipping away of human capital. ... I'm not discounting that. But on the flip side, I think there has been added value to human capital too. I have seen where human capital has been improved—they've gone back and gotten education when they wouldn't have [otherwise] been motivated to do it."

Job summary

Stern brought the retreat to a close by noting that the jobless recovery issue gets at a number of difficult, fundamental questions that economists continue to wrestle with.

"If you think about churning ... we have ongoing massive job changes in a market economy like the United States," Stern said. Roughly 3 percent of workers "are no longer working for the same firm month after month after month. It's difficult to absorb all of that quickly, and we don't have any mechanism that's going to assure that all of those people-especially if they are tied to a particular geographic location or to a particular skill set or to a particular industry—are going to be absorbed at their former or higher wage."

Understandably, policymakers want to soften the friction induced by that churn. But Stern noted, "I suspect that, assuming the numbers on churning are right, the size of the issue is such that there's really no effective way to address it from a public policy perspective, at least at reasonable cost. That doesn't mean we shouldn't do things that make the labor market work even more effectively than it currently does, and we can think about things" like improving information on occupational demand and the effectiveness of job retraining.

But these aren't silver-bullet strategies, Stern said; the problems have long resisted easy policy fixes. "Most of those ideas I remember discussing in my first course in economics in 1963. That still doesn't mean we ought to dismiss them, but it does suggest that, in some sense, maybe not all that much has changed."

*See Daniel Aaronson, Ellen Rissman and Daniel Sullivan, "Assessing the jobless recovery," Economic Perspectives, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, vol. 28, Second Quarter, 2004.

** Daniel Aaronson, Ellen Rissman and Daniel Sullivan, "Can sectoral reallocation explain the jobless recovery?" Economic Perspectives, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, vol. 28, Second Quarter, 2004.

For additional discussion, see “A dynamic economy means churning employment,” in the March 2005 issue of the fedgazette.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.