It was two years ago, in an interview with the French newspaper Le Monde, that the president of the European Commission, Romano Prodi, uttered the short but memorable statement, "la pacte de stabilité est stupide."

It was two years ago, in an interview with the French newspaper Le Monde, that the president of the European Commission, Romano Prodi, uttered the short but memorable statement, "la pacte de stabilité est stupide."

In any language, his message was stunning. According to the man charged with its implementation, the Stability and Growth Pact—the bedrock fiscal agreement of the European Union—was stupid.

The press had a field day—the stability pact was quickly labeled the "stupidity pact." Politicians demanded Prodi's resignation as head of the European Union's administrative agency. "The only thing that is stupid is Prodi's remark," retorted Finland's finance minister. But a week later, called before the European Parliament to explain his brash comment, Prodi simply repeated himself without apology. Rigid application of the Pact "is what I called, and I still call, stupid," he said. "I don't think it is the Commission's job to apply the rules in that way."

Though Prodi faced intense criticism from some quarters, others said he was simply voicing the reality that everyone already knew: Many countries were unwilling to live by the letter of the Pact's requirements. As France's finance minister put it, the Pact is a Procrustean bed, "too small for some, too big for others and a torture for all." For his part, Prodi claimed full support for the spirit of the agreement but said it needed to be applied more flexibly. If he had done nothing else, it was widely acknowledged, Prodi had opened up the debate over a long-festering issue.

It festers still.

Time for a change?

By all accounts, the Stability and Growth Pact—adopted in 1997—has not worked as intended. The Pact formalized the economic agreements of the Maastricht Treaty, the 1992 accord that gave birth to the European Union, and carefully spelled out the requirements for EU members to join in Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). Fifteen nations were judged to have met the requirements, and 12 of them elected to adopt the euro as their currency and cede their monetary policy to the European Central Bank (ECB).

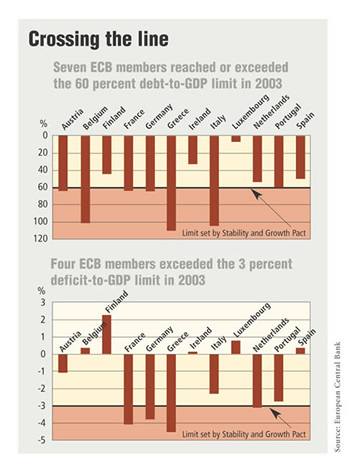

The Pact's key strictures are that EMU nations cannot run an annual deficit greater than 3 percent of gross domestic product or incur overall national debt greater than 60 percent of GDP. But in 2003, four of the 12 EMU nations went beyond the deficit threshold and seven surpassed the debt limit (see charts below). This year, six members are on course to exceed the 3 percent deficit bound. For France and Germany, which represent half the EMU economy, it will be the third straight year of deficit limit violation.

|

Debt vs. deficit: What's the difference? For the record, the United States doesn't meet the demands of the European Union's Stability and Growth Pact. The U.S. government deficit for fiscal year 2004 was $413 billion, roughly 3.6 percent of GDP. The U.S. federal debt as of October 2004 was about $7.4 trillion, or 63 percent of GDP. (Of this, $4.3 trillion (37 percent of GDP) was public debt, held by individuals, corporations and state, local or foreign governments. The remaining $3.1 trillion was intragovernmental debt, held in government trust funds, revolving and other special funds.) |

Enforcement has been lax, even though the Pact stipulates a clear schedule of penalties. Portugal was warned early on, as was Italy. But in November 2003, the EU's ministers of finance refused to enforce sanctions against France and Germany for exceeding the deficit threshold. (Ironically, it was at Germany's insistence that the Pact's deficit limits were adopted back in 1997.)

In early September 2004, Prodi and other EC officials issued a proposal for reform of the Pact, recommending that its requirements be tailored to each nation's economic situation and that greater leeway be provided in exceptional circumstances. "Both the identification of an 'excessive deficit' and the recommendations and deadlines to correct it may benefit from taking better into account the budgetary impact of periods of exceptionally weak economic growth," said the Commission's communiqué.

Prominent in debates over the wisdom—or lack thereof—of the Pact and its reform, have been central banks in EMU member states and the European Central Bank itself. A German Bundesbank spokesman, for instance, reportedly said that "instead of strengthening the Stability and Growth Pact, the proposed changes would have a generally detrimental effect." The ECB took a more conciliatory tone, welcoming improvements in implementation of the Pact as long as its wording remains intact.

The strong views of Europe's central banks might seem out of place. They are, after all, in charge of monetary policy, not fiscal policy. But the phrase Economic and Monetary Union (not European Monetary Union, as many mislabel EMU) is itself an explicit recognition that fiscal and monetary policy are intimately related, like the oars of a rowboat. If all goes well, they act in harmony, adjusting as necessary for unexpected gusts and waves, smoothly propelling the economy forward. But it doesn't take much to shatter the harmony, breaking the rhythm and swamping the boat. The Stability and Growth Pact was an attempt to keep things on an even keel.

But was Prodi right? Do tight fiscal constraints not make sense in a monetary union? Are the European Union's founding treaties unreasonably restrictive in limiting the budget flexibility of member states? Two economic theorists at the Minneapolis Fed suggest that, on the contrary, those who framed the Maastricht Treaty and the Stability and Growth Pact showed great foresight. Their argument relies on economic reasoning and mathematical models, so their conclusions are perhaps less dramatic than the political rhetoric of Europe's capitals. But if they're right, it isn't the Pact, but rather its critics, whose wisdom should be doubted.

Time inconsistency and free riding

"We now run the risk that, in the words of the old Chinese curse, we'll live in interesting times," said V.V. Chari in a recent interview. Chari, a professor of economics at the University of Minnesota and adviser to the Minneapolis Fed, is co-author of a November 2003 Fed staff report on the theoretical foundations of monetary unions like Europe's EMU, and he suggests that loosening the Union's fiscal constraints could create a severe trial for Europe's central bank. "If fiscal policy becomes profligate over the next few years, that's when the ECB's credibility will really be tested."

If EMU nations no longer feel strong pressure from fellow members to balance their budgets, suggests Chari, some may increase their national expenditures—and debt—substantially. Pressure will then grow on the ECB to lower member nations' debt burdens through inflation—that is, by increasing the Union's money supply so that each euro is worth less and the real value of nominal debts will decline. But of course, creating inflation contradicts the ECB's primary objective: price stability.

"It is not that the central bank does not have good intentions," notes Patrick Kehoe, Chari's co-author, and also an adviser to the Minneapolis Fed and professor at the University of Minnesota. "It's just representing the people on a day-by-day basis. But in these kinds of situations, representing the people on a day-by-day basis leads to bad outcomes, because once a member nation prints the debt, the bank inflates. Nations realize that will happen so they issue too much debt. The result: You get high inflation, high debt. Bad outcome."

According to Chari and Kehoe, the rationale for fiscal constraints in a monetary union has to do with a complex interplay between multiple fiscal authorities and a single monetary authority, where each watches the others and gauges the likely impact of its actions. Because decisions are taken sequentially—fiscal authorities make spending decisions, then the monetary authority sets the interest rate, and so on—time plays an important role in their analysis; the central bank is making decisions day by day, in Kehoe's words. Well-meaning policymakers who make their decisions by asking "what is the best I can do today?" end up with bad outcomes because their shifting policy is anticipated by rational onlookers. It's a phenomenon that economists call "the inconsistency of optimal plans."

And because a monetary union has just one central bank but many fiscal decision makers, free riding also plays a critical role. That is, individual nations will be tempted to enjoy the benefits of the union without paying their full share of the costs—riding in the rowboat but not pulling their weight.

It is this relationship between the potential for free riding and the day-to-day nature of decision making that can lead to bad outcomes if constraints aren't in place. More specifically, explain Chari and Kehoe, monetary authorities are naturally prone to change policy from one meeting to the next, responding to conditions current and anticipated. That policy inconsistency, observed by union members, leads nations to free ride—spending beyond their means, incurring national debts whose full costs they won't pay because the union's central bank will be motivated to inflate the debts away, a day-by-day monetary policy decision that spreads one nation's fiscal costs to all members of the union.

"The driving force behind our results is that a time inconsistency problem in monetary policy leads to a free-rider problem in fiscal policy," write Chari and Kehoe in "On the Desirability of Fiscal Constraints in a Monetary Union." "The time inconsistency problem arises because the monetary authority has an incentive to inflate away nominal debt."

Two problems, two solutions

Imagine, again, the rowboat, but expand it instead into a long racing shell with 12 fiscal rowers on one side and a big central banker on the other. If you're one of the fiscal rowers, two questions might occur to you (aside from how you ended up in this metaphor, but bear with me): First, how do we all stay in sync? And second, would anyone notice if I stopped pulling quite so hard? A strictly enforced Stability and Growth Pact ensuring that everyone rows at a set pace would answer both questions. But absent a fiscal pact, a lot depends on the monetary side.

If the big monetary oarsman is unshakably constant—a credible commitment to price stability—then every one of the fiscal rowers will know that he has to pull his weight or the boat will go off course.

But if the monetary oarsman is prone to change, pulling harder or softer in direct response to fiscal fluctuations, then fiscal rowers will have an incentive to slack off. They'll realize that if they stop pulling their weight, the monetary oarsman will react to keep the boat on course, easing up on his oar—just as a central bank might cave in to a nation's debt troubles by inflating them away. But the other rowers will pay a price: The boat will slow, dragged down by inflation.

Less nautically, monetary inconsistency induces fiscal free riding, and "the cost of inflation is borne by the residents of all the member states," write Chari and Kehoe. If each nation has to pay the full costs of its fiscal policy, rather than spreading its debts to neighbors through induced inflation, it will incur less debt. But membership in the union implicitly allows it to spend more than it could afford if left to its own resources, if and only if it knows that neither well-enforced fiscal constraints nor solid central bank commitment to price stability are in place.

"When a fiscal authority in a member state is deciding how much debt to issue," write Chari and Kehoe, "[it] takes account of the costs of the induced inflation on its own residents, but ignores the costs this induced inflation imposes on other member states. This free-rider problem leads to inefficient outcomes." Fiscal authorities will issue too much debt, with the understanding that the central bank will inflate away at least part of it, and the union's inflation rate will be too high.

Two solutions are possible, one fiscal. "Imposing constraints on the amount of debt that each fiscal authority is allowed to issue can ... make all the member states better off," according to Chari and Kehoe.

The other solution operates on the monetary side: Ensure that the central bank commits itself rigidly to price stability, regardless of national deficit situations. If nations know that the ECB won't inflate their debt away, they'll be less likely to incur debt. A credible commitment to price stability will eliminate time inconsistency and prevent free riding.

The framers of the Maastricht Treaty and the Stability and Growth Pact built in both mechanisms. They put tight constraints on fiscal policy. And price stability was enshrined as the fundamental goal of the ECB. "What we were trying to understand was, did these kinds of fiscal restrictions, and the statement about the primacy of price stability—did they make any sense?" says Chari. "And what we essentially argue is that both do make sense, both were attempts to arrive at the same goal."

But that comes with a strong qualifier: The fiscal restrictions make sense only if the ECB can't follow a credible committed policy of low inflation. If the ECB does commit to price stability, however, then the fiscal restrictions are "irrelevant and potentially harmful," says Chari. The economists' mathematical model shows that if monetary commitment is in place and there is no potential for free riding through induced inflation, then fiscal constraints aren't necessary since each nation will have to face the full costs of its national tax and spending decisions. Indeed, to the degree that they deprive governments of a valuable tool for easing the troughs of inevitable business cycles, fiscal constraints could be damaging.

"So at one level we're making a fairly straightforward theoretical point that there are arguments on both sides of the debate," Chari continues. "People who argue that the fiscal restrictions are harmful have a point, but they've got to be believing that these words about price stability have a special bite. And the people who set up the Treaty were suspicious of whether the words alone would be enough. So they also have a point about the necessity for fiscal constraints."

What is inconsistent, though, is the commonly held view that neither fiscal nor monetary authorities should be constrained. The idea that the ECB should change interest rates to counter short-term economic fluctuations and that fiscal authorities should face no constraints "is a recipe for disaster," says Chari. "And frequently the people who are opposed to these fiscal restrictions are also very strong proponents of an activist monetary policy to combat depressions and recessions."

You can't have it both ways, argue Chari and Kehoe. Discipline is necessary on either the fiscal or the monetary side.

A world currency?

In their analysis of monetary unions, Chari and Kehoe follow a long tradition in economics of seeking to understand the advantages and drawbacks of nations sharing a single currency. John Stuart Mill advocated wider monetary unions in his 1894 classic, Principles of Political Economy, but observed cynically:

So much of barbarism, however, still remains in the transactions of most civilised nations, that almost all independent countries choose to assert their nationality by having, to their own inconvenience and that of their neighbours, a peculiar currency of their own.

Why do nations insist on maintaining their own currency systems when a universal currency would so obviously ease transactions among them? As Mill implies, the desire to assert national identity is a powerful motive. The pride Americans feel in having George Washington on the dollar bill is no doubt lost on a native of Thailand, whose reverence for King Chulalongkorn, depicted on the nation's 100 baht bill, is similarly unappreciated in the United States.

But nations cling to their own money for reasons that go well beyond protection of heroes and heritage. Control of the national money supply affords a government substantial influence over domestic objectives; these are powers not lightly ceded to supranational bodies.

In 1961, Canadian economist Robert Mundell published a path-breaking article about optimum currency areas, explaining that nations joining a monetary union face a trade-off between the potential gains from reduced transaction costs (for example, the time and expense of changing one currency for another) and the possible losses due to diminished control over employment levels and inflation rates via the national money supply.

In Mundell's analysis, the more alike nations are in their responsiveness to macroeconomic shocks, the more advantageous a monetary union might be, since the union's central bank reaction to those shocks—necessarily aimed at the union "average"—would have a roughly equal impact in each country. If nations differ, however, the bank's monetary response would have too much influence on price levels in some countries and too little in others.

It's as if a town decided to economize on shoe manufacturing by making just size nines. That works well if feet range between sizes eight and 10. But if there's wider variation, some residents will have painfully pinched toes and others will slip and slide. Similarly, in a monetary union, members sacrifice the ability to individually tailor monetary stabilization strategies—if their economies vary widely, one size won't fit all.

Shaping the Union

Mundell's work on optimal currency areas, recognized years later with the Nobel prize in economics, was very influential in the design of Europe's monetary union. The "convergence" of member nations to similar macroeconomic standards is a key criterion of EMU accession, since a monetary union is beneficial only if nations are tightly correlated in their responsiveness to macroeconomic stabilization policies. A high degree of factor mobility among countries—easy cross-border flow of capital and labor—is a related prerequisite for a successful union.

Critics of Europe's monetary union tend to use the same criteria in finding fault. "My own judgement is that, on balance, a European Monetary Union would be an economic liability," wrote Harvard economist Martin Feldstein in 1997. "The gains from reduced transaction costs would be small. ... At the same time, EMU would increase cyclical instability, raising the cyclical unemployment rate."

But as economists Russell Cooper and Hubert Kempf point out in a September 2002 Minneapolis Fed staff report, arguments both pro and con tend to neglect the powerful role of fiscal policy. "Once national fiscal policies are properly taken into account, the trade-off between stabilization losses and transaction cost reductions from a common currency disappears," they argue.

And indeed, it is common in much analysis of monetary policy—not only that focused on monetary unions—to neglect the integrally related effects of fiscal policy, to study one in isolation from the other. It is a mistake not made by Chari and Kehoe.

"Any specification of monetary policy implies a corresponding specification of fiscal policy," notes Chari. "You can hide it in the background, but it's there." He and Kehoe explain that while many economists still ignore the intimate connections between fiscal and monetary policy, the link was famously demonstrated in a 1981 paper by then University of Minnesota professors Thomas Sargent and Neil Wallace, both former Fed advisers.

In "Some Unpleasant Monetary Arithmetic," Sargent and Wallace show that every government faces a single, consolidated budget constraint since any revenue raised by the central bank ultimately flows to the treasury. And that constraint enforces links between fiscal and monetary policy. If a government consistently spends more than it raises—a fiscal deficit—its central bank will eventually be forced to cover that debt through money creation. Sargent and Wallace prove that this means monetary policy ultimately has little permanent control over inflation if sound fiscal policies are not followed. Some level of coordination of fiscal and monetary policy is thus essential to maintain both economic growth and relative price stability.

"Take, for example, the hyperinflations of Argentina and Brazil," says Kehoe. "Attempting to study those situations made people totally aware that if you spend more than you tax, something's going to make up the difference, and often it's money [created by the central bank]. So trying to understand these huge, drastic monetary disasters without talking about fiscal policy didn't make a lot of sense."

Evolution

Sitting in a seminar room at the Minneapolis Fed, chewing sandwiches as they tag-team questions from a writer, Varadarajan Chari and Patrick Kehoe display an effortless give-and-take developed over years of collaboration. They finish one another's sentences, challenge each other on half-baked statements and step aside easily for their partner's contributions. "Lack of alignment could lead to some special problems with monetary policy," Chari explains, opening a segue. "Pat, you should expand on that." Kehoe does, at length.

The two have written at least 20 articles together over the last 15 years (some with other co-authors). Many of these pieces have focused on time inconsistency in fiscal policy—especially their 1989 article with Minneapolis Fed economist Edward Prescott, who won the Nobel prize in 2004 for his pioneering work on time inconsistency. But they've also explored free-rider problems, monetary policy issues, and cooperation vs. noncooperation among nations in economic policy setting. The current work reflects an evolution of their thinking, a synthesis of these various strands of economic analysis. "We've been floating around this subject in various ways for 18 to 20 years," observes Kehoe.

Chances are they'll continue to do so. With the current paper now submitted for publication, Chari and Kehoe may look into Mundell's question of optimum currency areas and examine the quantitative—not simply theoretical—aspects of the trade-offs that face nations when joining a monetary union.

"It's an old debate: What is the size of an optimal currency area?" says Chari. "Clearly our work on the monetary union bears on that. It's a statement about a particular group of countries being better off along some dimensions, worse off along other dimensions."

"There are theory pieces you do, which are fine, but this kind of question would be most interesting if you could put some quantitative analysis behind it," argues Kehoe. The hope, then, is to create a more sophisticated version of the model sketched out in the current staff report.

State of the Union

Regardless of their own research agenda, Chari and Kehoe's prognosis for Europe's monetary union is guarded. If Union policymakers loosen the Stability and Growth Pact, as the European Commission is proposing, the effect on the Union will depend on the central bank's ability to commit to price stability, a commitment that Chari and Kehoe contend has yet to face a difficult test.

"What our theory says is, if you think that the ECB has not attained complete commitment, then you're going to see bad outcomes," says Chari. "If the ECB has attained that commitment, then they shouldn't restrain fiscal policy. So the key issue is, does Jean-Claude Trichet think the ECB has attained so much credibility that these restrictions are now pointless."

In his interview with The Region, Trichet expressed confidence in the central bank's steadfast commitment to price stability. And while the ECB would support improvements in implementation of the Pact, he said, "where we are not comfortable is when there is a call for loosening the corrective arm," which specifies exceptions, timing of corrective sanctions, and the numerical deficit and debt thresholds. "We really trust ourselves that the nominal anchor of the 3 percent should not be touched."

Indeed, Kehoe is concerned that loosening the Pact's constraints might begin a gradual process of weakening. "It could be the kind of thing where constraint slips away slowly, but there's no big test immediately," he says. "If the constraints are abused a little bit, not tremendously, and then five years down the road there's some massively bad recession, debt starts flying, well, that's when the central bank will get tested."

So while the current situation might not be dire, relaxing fiscal constraints without certainty of monetary commitment would be unwise, suggest the economists. "They might be sowing the seeds today for a disaster a decade from now," says Kehoe. "And then they're arguing 'it's okay because we haven't had a disaster right now.' That's like arguing that I don't need fire insurance because my house has not yet burned down."

"I don't know whether ECB credibility is a real problem or not. We're going to find out," says Chari. The first years of the monetary union haven't truly tested the central bank's resolve because the stability pact has managed to restrain member nation debts. "The last six years have been a time when EMU fiscal policy in relative terms-certainly relative to the United States over the last couple of years-has been somewhat more responsible," he suggests. "So, ECB policymakers haven't really been tested. We'll see what happens when they are."