If you were to lose your job tomorrow, how would you survive? How would you put food on the table, a roof over your head?

With luck and effort, you'd soon find a new job. With foresight, you've squirreled away some savings. But many of us, to some degree, would rely on Uncle Sam and the regular checks that come from the unemployment insurance system established in 1935, in the midst of the Great Depression.

Decades later, this program provides workers who lose their jobs "through no fault of their own"—as the Department of Labor gently puts it—with payments of roughly half their previous job's wage for as long as six months. On an average week in 2003, about 3.5 million U.S. workers received unemployment checks, resulting in annual state and federal outlays of $39 billion.

But insurance has peculiar effects on people, inducing them to do things they wouldn't otherwise. Insuring bank deposits, for instance, can lead depositors to ignore a bank's risky investments. Economists call this moral hazard: insurance inducing people to take risks they wouldn't if they were uninsured.

Unemployment insurance can also alter behavior. If workers receive government payments while they're out of work, they might put less effort into looking for a new job—reduced "search effort," an economist would say. Or they might demand higher pay before they'll take a new job—a higher "reservation wage." Such distortions waste their labor and misallocate the economy's resources.

Many economic studies of unemployment insurance policies have focused on these distortions and concluded that benefits should decline over time so that workers are less inclined to stay unemployed. It's a conclusion that makes intuitive sense, and in the United States, government programs implement it sharply: After six months or so, benefits dry up.

Misleading conclusions

But recent work by the University of Chicago's Robert Shimer and Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Iván Werning, a visiting scholar at the Minneapolis Fed this past fall, suggests that these common beliefs about unemployment insurance may themselves be distorted. "On the surface, these models told economists that systems that had benefits falling with the duration of unemployment were a good idea," said Werning in a telephone interview from Harvard, where he's spending the second half of a year's leave from MIT. "We found that that was a highly misleading conclusion."

If an unemployment insurance program is properly designed, their research suggests, benefits should be constant over time, not declining. But this well-designed program has another requirement: Workers must be able to borrow and save. "The general message that emerges from our model is that unemployment insurance policy should be simple," write Shimer and Werning in their Minneapolis Fed staff report 366, "a constant benefit and tax, combined with measures to ensure that workers have the liquidity to maintain their consumption level during a jobless spell."

A simple government program? Constant unemployment benefits? These sound like the pipe dreams of theoretical economists, and indeed, Shimer and Werning admit that their theory contradicts both conventional wisdom and current policy. But by carefully analyzing how society can provide both insurance and incentives for its workers, they tackle one of the most vexing conundrums of macroeconomics.

"Individuals face a great deal of labor income risk," noted Shimer, from Chicago. "It's one of the most important sources of uncertainty." Insurance can mitigate that risk, just as it does for health, housing and automobiles, and for economists the challenge is determining the most efficient means of doing so. "Our goal," he said, "is to try to understand the optimal structure of unemployment insurance."

Policy relevance

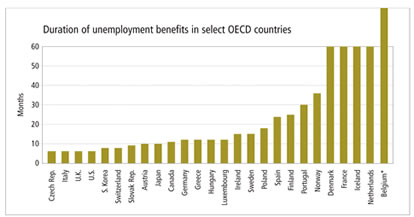

That the structure is still in question is reflected in the broad range of national policies among industrialized nations. Unemployment benefits in Italy and the United Kingdom run out after six months, as they do in the United States. But German, Greek and Luxembourgian workers receive government checks for a full year. Unemployment benefits continue for five years in Denmark, France, Iceland and the Netherlands. And Belgians can receive unemployment benefits indefinitely (see chart). And while unemployment insurance payments represent a relatively small proportion of gross domestic product in the United States (0.4 percent in 1990), some nations spend much more: In the late 1980s, the Netherlands spent 3.4 percent of GDP on unemployment insurance.

|

|

Source: OECD Benefits and |

*Duration is unlimited in Belgium. |

Policy toward the unemployed has dramatic political implications in any nation. Even though unemployment is currently at a four-year low in the United States, workers remain concerned about job losses, especially those related to trade and outsourcing. Allaying those worries with good unemployment insurance might ease acceptance of free trade policies.

"I think if people were a bit less fearful of the impact of change on their own financial well-being they might be more amenable to arguments that trade is highly beneficial to the economy as a whole," observed Ben Bernanke, then a Fed governor, in a 2004 Region interview. "I think there is a legitimate issue arising from the fact that you can't buy insurance against losing your job to new foreign competition, so that workers who are displaced by trade bear most of the associated costs, rather than society at large."

Another prominent economist, Harvard's Martin Feldstein, president of the National Bureau of Economic Research, has developed an unemployment policy proposal that resonates with current White House proposals for personal health savings accounts and individual retirement accounts. In his 2005 presidential address to the American Economic Association, Feldstein proposed that workers be required to establish "Unemployment Insurance Savings Accounts." They would pay into an individual account while employed, building up a balance sufficient to pay benefits for two spells of six months at half their wage, and to be drawn upon during spells of unemployment. If they retire or die with a positive UISA balance, workers or their heirs can use the funds as they wish.

It's an idea that finds support in Shimer and Werning's research, but by stringing together "insurance" and "savings" in his label for the accounts, Feldstein melds concepts that Shimer and Werning seek to differentiate.

Job benefits

But first, some background. The search for optimal unemployment insurance, like much economic research, involves a balancing act weighing costs against benefits. The bulk of research on unemployment insurance has focused on the costs. And those costs may be quite substantial.

An often-cited 1990 study by economists Lawrence Katz of Harvard and Bruce Meyer of Northwestern University looks at two sets of data on U.S. workers—a national sample of household heads who were unemployed in 1981 because of layoffs or plant closings, and a database of the wage and benefit histories of over 3,000 workers in 12 states from 1978 to 1983.

Katz and Meyer estimate that extending unemployment benefits by one week would increase an average unemployment spell by "approximately 0.16-0.20 week"—a figure that falls within a range of 0.1 week to 0.33 week found in related studies. (They also find that increases in benefit duration have a stronger impact on extending unemployment than do increases in benefit level.) Extending unemployment by a fifth of a week may not sound like much, but it adds up. "An increase in potential benefit duration from 6 months to 1 year," they write, "is predicted to increase mean duration of unemployment by 4-5 weeks."

Unemployment insurance affects employers as well. If workers can get unemployment payments while they're out of work, they'll be more willing to work in industries and companies that tend to lay off their workers on a seasonal or cyclical basis. "That reduces the wage that such firms have to pay," said Feldstein in his 2005 speech, "and thus subsidizes the expansion of those high unemployment industries."

But economists point out that unemployment insurance also offers unambiguous advantages. It may provide for a better matching of workers and jobs since it allows workers to be more selective about which job they take; a better match means higher productivity. And there's the program's more deliberate goal: It cushions the financial blow inflicted by losing a job. That is, it allows the unemployed to smooth their consumption, so that losing a paycheck doesn't mean starvation.

In a 1997 article, MIT economist Jonathan Gruber examines the consumption smoothing benefits of unemployment insurance by looking at reported expenditures on food by a national sample of heads of households over the period from 1968 to 1987. Unemployment is associated with a drop of food consumption of 6.8 percent, he finds, but in the absence of unemployment insurance "becoming unemployed would be associated with a fall in consumption over three times as large" (italics in original). The data show that roughly half of the unemployed individuals had savings before they lost their jobs, but "only 18.6 percent have savings of more than two months of income"—indicating the importance of unemployment insurance for longer spells of unemployment.

Optimal policy

Noting these positive effects of unemployment payments but also their high costs, Gruber and others have tried to estimate optimal policy: an unemployment insurance program that could provide the greatest advantage at the lowest price, thus maximizing social welfare.

It isn't a trivial task. The analyst has to build a model that interlinks consumption, wages, employment taxes, unemployment insurance benefits, interest rates, discount rates and risk aversion. The last is important because workers with a high tolerance for risk need less insurance, whereas those with high risk aversion get great utility from insurance. Assumptions about risk tolerance therefore have a strong bearing on optimal insurance.

Gruber's model indicates that if one assumes a low level of risk aversion, optimal unemployment benefits are zero. Even at a very high degree of risk aversion, he finds, the replacement rate—the percentage of a worker's previous wage represented by the unemployment benefit—is below 50 percent. "Thus, despite large consumption smoothing effects," writes Gruber, "the distortions of UI to search behavior are so large that the optimal benefit level is fairly low. … [I]n almost no case is the optimal replacement rate much higher than current levels, and it is generally lower."

Other economists have examined the same problem with different models and assumptions, looking for the right level or time path of benefit payments. An influential 1979 article by Steven Shavell of Harvard University and Laurence Weiss at Yale determined that to provide appropriate incentives, benefits should decline over time, tending toward zero. "A declining sequence is desirable (individuals are induced to get jobs sooner, at least on average) even though it reduces the role of benefits as insurance," they write.

In a 1997 article, using a more sophisticated model that includes a wage tax on workers after they regain employment, Hugo Hopenhayn, now at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Juan Pablo Nicolini of Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, confirm Shavell and Weiss' conclusion: Benefits should decline. "The optimal unemployment insurance contract," write Hopenhayn and Nicolini, "involves a decreasing sequence of insurance payments to the worker while unemployed, followed by a constant tax rate after reemployment."

Hopenhayn and Nicolini explain in their article that the optimal contract, through the wage tax, "punishes" workers for remaining unemployed by reducing their claims on future consumption—thereby reducing the incentive problem. Moreover, they estimate that implementing their proposed policy could reduce the cost of unemployment insurance dramatically, as opposed to the moderate savings produced by Shavell and Weiss' policy option, without reducing overall worker utility. "The gains are particularly large (about 30 percent) for [workers] with no wealth or other source of income and with no access to borrowing."

Saving grace

Shimer and Werning take a different tack. Rather than allowing just a single decision about how much effort a worker will put into searching for a job, as in Hopenhayn and Nicolini's model, Shimer and Werning use a sequential search model, in which an unemployed worker repeatedly decides whether to take a job or stay on unemployment. While their results don't hinge on this sequential model, they argue that it's empirically relevant and more closely aligned with most research on equilibrium unemployment.

More crucially, their model allows workers to borrow and to save. Most analyses of optimal unemployment insurance, they point out, conflate two key roles played by unemployment insurance payments: They offer a hedge against the uncertainty of finding a new job and they help workers smooth consumption. In short, unemployment relief programs provide both insurance and liquidity. By building a model that explicitly separates these roles, suggest Shimer and Werning, economists can better understand the true nature of unemployment benefits.

"Our model suggests thinking about designing a system that distinguishes between them," says Werning, "making sure that workers have enough liquidity and then thinking about what the right level of benefits that act as insurance would be."

And this distinction makes all the difference. "When workers have sufficient liquidity, in either assets or capacity to borrow," they write in their staff report, "a constant benefit schedule of unlimited duration is optimal or nearly optimal." Constant benefits—payments that continue no matter how long the unemployment spell—insure against unemployment risk, "while workers' ability to dissave or borrow allows them to avoid temporary drops in consumption."

Again, Shimer and Werning's is a sequential search model. In it, workers are either employed or not, and there's an insurance agency—that is, a government—that provides unemployment benefits to those out of work and levies employment taxes on those with jobs. Workers try to maximize their utility, and the agency tries to minimize the cost of providing that utility. Workers who have jobs keep them forever (remember, it's a model), but those without have to decide at each time period whether to accept a new job at the wage offered them. This sets up the crucial dynamic: providing payments to unemployed workers that are sufficient to keep them from starving, but not so high as to dissuade them from taking a reasonable job offer.

Using this model, Shimer and Werning compare two policies. The first is an "optimal unemployment insurance" setup similar to Hopenhayn and Nicolini's in which the agency can directly control the worker's consumption, with workers spending as much as they earn in any given time period. This policy mitigates the incentive distortions that insurance creates because the insurance agency, rather than the individual, controls how much an individual consumes. It's a hand-to-mouth existence, but it's economically optimal.

The second is a "constant benefits policy" in which workers who are unemployed receive steady government payments for as long as they're without a job, and employed workers pay in a steady tax out of their wage to fund those benefits. Under this second policy, workers can borrow or save, so in any given time period, they might consume more or less than they've earned.

Having built the models, the economists evaluate the interactions of the variables over time under both policies, paying particular attention to the flows of worker consumption, employment taxes, the unemployment subsidy (the additional resources that a worker gets by remaining unemployed) and the reservation wage.

Perfect equivalence

What they find is both remarkable and compelling. Under a certain set of assumptions about risk aversion, there is no difference in cost between optimal insurance and constant benefits policies.

"[W]ith constant absolute risk aversion preferences and no lower bound on consumption, constant benefits and optimal unemployment insurance are equivalent," they write. "That is, the cost of providing the worker with a given level of utility is the same, her reservation wage is the same, and the path of her consumption is the same under both insurance systems."

The results are remarkable because they contradict the standard story that benefits should decline over time in order to induce the unemployed to accept jobs, and compelling because they suggest an unemployment insurance policy that is simple, pragmatic and optimal.

It bears emphasis that even though both have declining benefits, real-world unemployment insurance programs are not "optimal unemployment insurance" as portrayed in conventional economic models. The latter usually assume that governments can control workers' consumption levels. Hopenhayn and Nicolini, for instance, write, "Assume that the worker has no other source of income and that the principal can directly control his or her consumption."

This crucial assumption is, of course, not very realistic. For all their power, governments aren't able to perfectly monitor and control consumption. The appeal of Shimer and Werning's model is that it doesn't rest on this assumption, yet still achieves optimality.

Risky business

Or nearly so. Shimer and Werning find perfect equivalence between optimal insurance and constant benefits, but this finding also depends on an unrealistic assumption—about risk aversion. Specifically, in their first run-through of the model, Shimer and Werning assume that people are no more risk averse when they're poor than when they're rich. In fact, though, most economists believe that the fewer assets you have, the more cautious you'll become. So rather than assume absolute risk aversion, Shimer and Werning next run the model under an assumption of relative risk aversion.

The equivalence between optimal insurance and constant benefits disappears—but just barely. For most realistic scenarios, they find, the difference in cost between the two policies is nearly zero: "If the worker has enough liquidity so as to have a minimal chance of approaching any lower bound on assets, the additional cost of constant benefits is minuscule, less than 10-7 weeks (or about 0.01 seconds) of income in our leading example."

At the core of the result is the intuition that people don't really need an outsider to tell them to stop spending what they don't have or aren't likely to earn. As Milton Friedman's well-known "permanent income" hypothesis says, people adjust their spending to what they perceive as their long-term income level. Standard models of unemployment insurance have concluded that the only way an insurance agency can maintain work incentives is to steadily reduce consumption by steadily reducing benefits. But Shimer and Werning show that people realize their limits without Big Brother's help.

"When you allow for savings," explains Shimer, "it's very natural, as long as the unemployment benefit is less than the wage you would get, to draw down your savings, and in response to that, consume less and less." If they have assets, adds Werning, "the unemployed, on their own, will have a declining path of consumption. ... The conclusion from this analysis is that the declining path of consumption does not imply a declining path for insurance benefits."

The right level

Which prompts the question: If benefits should be constant, at what level should they be set? In a draft paper (via University of Chicago, PDF) released in February, the economists use their model to focus on the optimal level of that constant benefit. "The main insight," says Werning, "is that the reservation wage provides the answer." Adds Shimer, "We argue that what optimal unemployment insurance benefits should do is maximize the after-tax reservation wage of workers."

The reservation wage—the lowest wage a worker will accept—minus the taxes needed to fund unemployment benefits is a perfect summary of a worker's welfare, they find. "The intuition is clear," write the economists. "[T]he after-tax reservation wage tells us the take-home pay required to make a worker indifferent between working and remaining unemployed. Since take-home pay translates directly into consumption, it is a valid measure of the worker's utility."

While higher benefits raise the before-tax reservation wage by reducing the cost of staying without a job, those higher benefits must be funded through an increase in the employment tax. If workers raise their after-tax reservation wage, they're thus revealing that their welfare will be improved by higher benefits, even though they'll collectively have to pay for those benefits.

The question then is, How responsive are reservation wages to benefit levels? Empirical research by Feldstein and others indicates that reservation wages are quite sensitive to unemployment benefits—that is, if unemployed workers get high unemployment benefits, they're very likely to demand a higher wage. "For us, that's a sign that unemployment benefits are making the unemployed actually much better off," says Shimer. "And that would be an argument for raising unemployment benefits."

Or as Werning puts it, "An increase in the benefit level with a budget-balancing increase in taxes, if you were to implement such a change in our model and you found that the reservation wage of the unemployed went up, that tells you that this is a good policy move." Since the unemployed worker realizes he'll eventually have to pay back the benefits he's receiving, he's revealing through his reservation wage (after taxes) his utility. Adjusting benefits to that point is the optimal move.

Turning heads

If the conclusion about constant benefits was remarkable, this finding is revolutionary. "It turns on its head previous evidence," says Werning. Most economists have assumed that the sensitivity of reservation wages to unemployment benefits is an indication of moral hazard-that by increasing insurance levels, governments were inducing the unemployed to avoid work. "Our analysis turns that interpretation on its head. If you're trying to help the unemployed, it's a good thing that they're so much better off that the point of indifference is higher."

On the other hand, some empirical evidence suggests that reservation wages aren't really that sensitive to unemployment benefits. If that's the case, Shimer and Werning's model argues that current benefit levels are too high. "An important goal for future empirical research," they conclude, "should be to obtain more precise estimates of how labor market policies affect reservation wages."

They also point out that because after-tax reservation wages measure the well-being of unemployed workers, they are useful in evaluating any policy toward the unemployed, not just insurance benefits. Optimal severance payments or training subsidies, for example, can also be estimated. "The key question," they write, "is whether the policy raises the after-tax reservation wage."

Shimer and Werning's ideas are certainly not the last word in economic theory about unemployment insurance, but there's no doubt that their provocative message will cause economists to rethink the way they analyze the question. Research to date had begun to reach a consensus that to minimize the distortions caused by unemployment insurance, benefits should decline over time, and should probably be much lower than they currently are.

But by carefully distinguishing between the roles of liquidity and insurance, Shimer and Werning suggest that a simple and pragmatic policy might instead keep benefits constant and possibly at a level higher than at present, as long as the government also allows workers to borrow and save. "It's a disarmingly simple argument," says Werning. "And we hope it's also useful."