Since the mid-1960s, financial institution supervisors have had the ability to take enforcement actions against financial institutions1 that were operating outside the boundaries of safe and sound banking practices.

Enforcement actions have been a key component of the supervisory tool kit for 40 years. However, the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act significantly enhanced the tools available to ensure that banks and thrifts comply with laws and regulations and avoid unsafe practices that could lead to failure.

Enforcement actions have been a key component of the supervisory tool kit for 40 years. However, the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act significantly enhanced the tools available to ensure that banks and thrifts comply with laws and regulations and avoid unsafe practices that could lead to failure.

Key changes in supervisory powers resulting from the 1989 and 1991 legislation are outlined in the "Changes Resulting from FIRREA and FDICIA." At the time, some commentators forecasted that supervisors would overuse and misuse the tools that were added via FIRREA and FDICIA. Many observers felt FDICIA "may undermine banks further," according to the Wall Street Journal. Some said the legislation was "shortsighted." Others suggested that the "arbitrary, Draconian and inflexible" system might prevent bank failure but would likely also prevent banks from prospering.2

It is true that fewer banks have failed. Since January 1994, only 57 banks and 13 thrifts have failed, with a recent record of 26 consecutive months without a failure as of Aug. 31, 2006. This compares favorably with more than 1,536 bank failures and 1,384 thrift failures from 1980 to 1993. At the same time, financial institutions have prospered. On Feb. 28, 2006, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. announced that 2005 represented the fifth consecutive year of record earnings for the industry. The fear that financial institutions could not prosper under the new regulatory structure was clearly overstated. Less certain is whether banking and thrift supervisors have acted in an "arbitrary, Draconian and inflexible" way when using the new tools of FIRREA and FDICIA. This article seeks to answer that question.

We start by examining the number and nature of enforcement actions taken over the past 15 years. Through a review of the trends in the number of, types of and reasons for enforcement actions taken against both institutions and individuals and comparing those trends with changes in banking conditions, we conclude that the dire predictions have not come to fruition. Rather, we find that the number and severity of enforcement actions generally track supervisors' assessments of banking conditions. In addition, our analysis reveals that in a period in which the industry has experienced solid, even record, earnings, enforcement activity has been largely driven by regulatory focus on risk management, compliance and similar issues. In periods of strong industry financial performance, management integrity and compliance with the law play a key role in determining the appropriate supervisory response—most notably revealed in the trends in civil money penalty assessments. The article concludes with a look forward to potential implications of these trends for the future. We remind the reader that the views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve.

The road to FIRREA and FDICIA

The last prolonged crisis in banking dates back to the 1980s when inflation rates were high and many financial institutions were strained by the loss of deposits to non-bank or thrift institutions offering higher yields. Economic challenges of many types and in many geographic markets, along with Depression-era legal restrictions on banking industry activities and practices, added to these difficulties and hampered the ability of financial markets to recover. This led to pressure for structural change and, in some cases, unwise expansion of some banking organizations into volatile markets. Loan losses mounted in many areas, in particular, agriculture and commercial real estate. Bank and thrift failures resulted from this untimely cocktail.

The state of the banking industry in the late 1980s led to the overhaul of the banking laws and regulations that ensure the safety and soundness of banks and thrifts. In addition to stronger capitalization requirements and overhaul and recapitalization of the deposit insurance system, the regulatory tools available to federal financial institution supervisors—the Federal Reserve System (FRS), Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC), Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS)—were significantly enhanced as noted in the sidebar. Supervisors could now require changes in financial institution management, more completely remove officers and directors, restrict growth, suspend dividends and/or require institutions to put together plans to increase capital levels.

The concerns about the new banking laws and regulations giving supervisors new powers were many. Some thought the new laws went too far. They believed that supervisors would use the "big stick" of formal enforcement actions too often and exacerbate problems at middling banks. Others believed the civil money penalty powers were particularly troublesome, especially the ability to fine individuals for infractions and to impose civil money penalties of up to $1 million per day for any violation of law. Concerns were also expressed that the institution-affiliated party provisions would lead attorneys and accountants to flee from representing problem banks and thrifts. Finally, the fact that formal enforcement actions could now be published in the local newspaper led some to believe that institutions with large amounts of uninsured deposits would incur bank runs and that examiners would not be forthcoming with their conclusions.

While much of the evidence that would allow an observer to refute or confirm these predictions remains confidential—supervisors only disclose the final action, not the findings that led to imposition of the action—publicly available information does give insight into the regulators' use of these powers. From these data and the lack of significant bank failures since the enhancement of supervisory powers, we can infer that the supervisors continue to exercise prudence in the use of their enforcement powers.

Enforcement actions

One of the side effects of the requirement in FIRREA to publicize formal enforcement activity is that it is easier for anyone to track enforcement practices. Prior to the effective date of FIRREA, all enforcement actions were considered confidential, making any comparisons to the period before enactment impossible. Since Aug. 9, 1989, formal enforcement actions have been made public. Federal bank and thrift supervisors now maintain lists of formal enforcement actions issued on their public Web sites. In addition, more recent formal enforcement actions can be viewed electronically from a link available in the search function. The availability of these data allows for a more detailed look at formal enforcement actions and trends than was possible prior to FIRREA. (See "Types of Enforcement Actions.")

The data included in this article are drawn from the information maintained on the agency Web sites. The Web sites maintained by each agency vary—in particular, the search features and level of detail differ by agency. For example, the OTS Web site does not include enforcement actions against institutions prior to 1994. In addition, the date after which all formal enforcement actions are linked to the search function varies by agency. The differences in the available data place some limits on the level of analysis that is possible. As a general rule, with minor exceptions, all formal enforcement actions issued in 2000 and thereafter are available via online links.

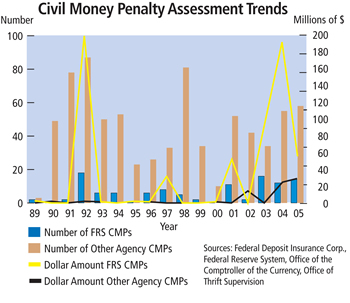

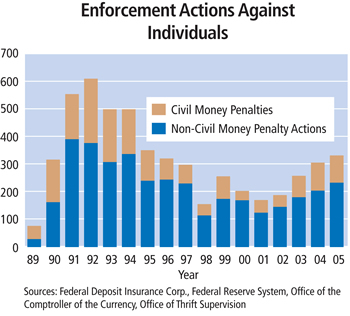

As shown in the charts above, the number of enforcement actions peaked in 1992, with 592 enforcement actions taken against institutions and 612 enforcement actions taken against individuals. Activity declined significantly in the late 1990s, hitting lows of only 81 enforcement actions against institutions in 1996 and only 156 enforcement actions against individuals in 1998. (Figures for 1989 are excluded because only formal enforcement actions issued after Aug. 9, 1989, are public.) In years where there is heavy enforcement activity, enforcement actions against institutions are concentrated in the areas of cease and desist orders and written agreements, with civil money penalties falling far behind. This gap is significantly reduced in years where activity is substantially lighter, with the narrowest gaps noted more recently. Indeed, the number of civil money penalties against institutions peaked in 2005, while the amount of penalties peaked at over $213 million in 2004.

Enforcement actions track conditions (mostly)

The results shown in the charts are not surprising and generally closely track banking conditions (as shown in the graph below). When there are more banks in less than satisfactory condition (CAMELS rated 3, 4 or 5; see examination ratings), the number of enforcement actions taken against institutions and individuals tends to be high. While the number of formal enforcement actions taken peaks in 1992, the percentage of institutions in less than satisfactory condition peaks in 1991. This is due to a lag effect, since enforcement actions are generally taken after examination results are final. In addition, because they are enforceable and public, formal enforcement actions can take considerable time to draft, negotiate and execute.

Included in the enforcement actions against institutions displayed in the chart (above) are Prompt Corrective Action directives. These enforcement actions were expected to be among the most inflexible of the new enforcement tools because FDICIA mandated that they be issued in the event that specific minimum capital levels were not maintained. The statute also outlined specific provisions that were to be included in the action based on the financial institution's capital level. The evidence to date does not support the fear that PCA directives would be used frequently and inflexibly. While over 300 institutions have failed since the Dec. 19, 1991, enactment of FDICIA, only 43 PCA directives have been issued against 35 financial institutions, 17 of which ultimately failed. The small number of PCA directives relative to the total number of failures is likely due to two factors. When failures result from fraud, the transition from apparently sound condition to insolvency tends to occur quickly, leaving no time for implementation of a PCA directive. Conversely, for failures resulting from poor asset quality, the weaknesses leading to failure are often evident and addressed in other types of formal enforcement actions well before the PCA capital triggers are met. This is particularly true since FIRREA clarified the supervisors' authority to require affirmative measures, including capital injections, in cease and desist orders and written agreements.

Throughout the period, the number of formal enforcement actions taken against institutions closely tracks the percentage of institutions in less than satisfactory condition. It can be concluded, therefore, that the factors leading to less than satisfactory ratings and those warranting enforcement activity against institutions are closely correlated.

While the trend lines for formal enforcement actions and banking conditions track closely, we must be careful to not draw determinative conclusions about the financial condition of banks and thrifts based on enforcement activity. Whereas in the past examiners focused primarily on financial ratios and trends in developing their assessment of the overall condition of an institution, they now take a broader view. This is particularly true in the past five years, as examiners have increasingly focused on the strength of risk management activities and corporate compliance functions in assigning composite ratings and determining appropriate enforcement actions. The focus on risk management and compliance has resulted in lowering ratings and pursuing enforcement actions before weaknesses are reflected in financial performance. By identifying root causes of financial decline early, examiners seek to prevent a recurrence of the conditions leading to banking crises like those experienced in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Enforcement actions taken against individuals, while generally following the overall trend line (except for a recent increase), do not track the changing conditions of institutions as closely. A number of factors contribute to this less precise relationship. Often a single transaction that results in one or two enforcement actions against an institution will include civil money penalty assessments and cease and desist orders or removals against multiple individuals—increasing the individual count. In addition, enforcement actions against individuals tend to lag the related action against institutions for the following reasons.

- In most cases the timeliness of the institutional enforcement action is more critical as supervisors give greatest priority to actions designed to correct existing and prevent future problems before further deterioration occurs. In the case of enforcement actions against individuals, there is often somewhat less urgency, particularly with respect to actions that have a punitive aspect such as civil money penalties.

- Supervisors often focus first on stemming losses and curtailing dangerous practices and only later on determining which individuals were sufficiently culpable to warrant individual enforcement actions, a process that is often time consuming.

- Individual enforcement actions appear to be contested more than institutional enforcement actions, meaning these actions are more time consuming to put in place.

A good example of the impact of these factors is the Bank of Credit and Commerce International case, which involved a major international bank that illegally acquired control of U.S. banks, was involved in widespread fraud and engaged in other unseemly activities. BCCI resulted in three corporate cease and desist orders in 1991 and a substantial corporate civil money penalty in 1992. The same case resulted in nearly 30 enforcement actions against 20 separate individuals between 1991 and 1998.

Other observations on enforcement actions

Drawing from our survey of formal enforcement actions over the past 15 years, we can make a number of observations about the types of enforcement actions being issued. First, institutions are increasingly likely to sign a written agreement versus a cease and desist order. Second, recent enforcement actions have an increased focus on the compliance aspects of performance rather than traditional safety and soundness concerns, such as asset quality and capital adequacy. Third, the trend toward a compliance focus is particularly evident in the area of civil money penalties.

Types of enforcement actions executed

Three of the supervisors (the FRS, OCC and OTS) use both cease and desist orders and agreements that meet the statutory definition of a written agreement. (Although each supervisor has a different name for this type of enforcement action, the term "written agreement" is used in this article for consistency with the statute.) Both cease and desist orders and written agreements outline corrective actions that a financial institution's management and directors must take to address noted deficiencies in the institution's operations. In the hierarchy of enforcement actions, cease and desist orders are second in severity only to termination of deposit insurance proceedings. Thus, while cease and desist orders and written agreements often can accomplish the same goals, the written agreement is perceived as a less severe enforcement action. One significant distinction between these enforcement actions is that written agreements can only be issued with the consent of the institution, whereas cease and desist orders can be issued without consent after administrative hearings.3

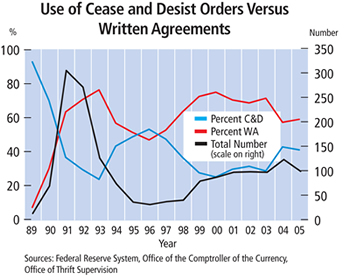

The relationship between written agreements and cease and desist orders is shown in the graph above. The data show a significant reduction in the use of cease and desist orders relative to written agreements starting in 1991. While the use of written agreements relative to cease and desist orders fluctuates over this time horizon, with the exception of 1996, the written agreement tends to dominate over the cease and desist order, although the gap appears to be narrowing in 2004 and 2005.

The increased relative reliance on written agreements is not surprising. Few enforcement actions, regardless of type, are entered into as a result of contested proceedings. For whatever reason, be it that institutions tend to recognize the need for corrective action or shy away from public notices of charges and hearings, nearly all cease and desist orders are issued with the consent of the entity. As a result of FIRREA, both written agreements and cease and desist orders offer the same level of transparency and market discipline. In addition, also as a result of FIRREA, both actions are enforceable under section 8 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act. What FIRREA did then, was to reduce the difference between these types of formal enforcement actions from the supervisors' perspective to the two factors noted previously: The cease and desist order remains the only corrective action that can be issued without consent and the public perception of the seriousness with which the agency views the activity giving rise to the enforcement action.

From the institution's perspective, however, the difference may be significant. The public nature of formal enforcement actions results in the language of the action creating a clear incentive to sign a written agreement. Institutions prefer to have the enforcement action portrayed as an agreement between the organization and the supervisor to take specified actions to address mutually identified weaknesses rather than as an order from the supervisor to correct deficiencies identified by it.

Given the limited difference in transparency and enforceability and the clear preference of entities for written agreements, why then are approximately 40 percent of non-civil money penalty formal enforcement actions still in the form of cease and desist orders? Because of the confidential nature of examination findings, a definitive answer to this question is not possible. However, the data do provide some insights into the supervisors' criteria for pursuing different types of enforcement actions. As shown in the table below, a review of actions issued by the FRS between 2000 and 2005 reveals that during that time few cease and desist orders dealt primarily with traditional safety and soundness weaknesses, such as poor asset quality. Conversely, over half of all written agreements were primarily related to traditional safety and soundness weaknesses.

The rest of the cease and desist orders were primarily related to noncompliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and other Anti-Money Laundering standards (BSA/AML), noncompliance with an existing written agreement or application conditions and formation of an illegal bank holding company. While not all BSA/AML enforcement actions were cease and desist orders instead of written agreements, written agreements tended to be used for first-time issues or small institutions. Conversely, cease and desist orders were used for larger organizations and those with past BSA problems. In addition, the use of cease and desist orders rather than written agreements expanded after the July 2004 publication of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations' report on the Riggs National Bank matter. From these data we can surmise that the supervisors' perceptions of management integrity and compliance with law are key factors in determining which type of formal enforcement action to pursue. In addition, it is likely that supervisors are sensitive to the implications of the more transparent atmosphere promoted by FIRREA.

Recent enforcement actions reflect compliance focus

The FRS is not alone in its increased focus on compliance in assessing the condition of institutions. This, in turn, has led to increased enforcement activity in this area. During the period from 2000 through 2005, an increasing percentage of formal enforcement actions addressed compliance with the BSA and other AML standards. In 2000, 11 percent of all non-civil money penalty enforcement actions were primarily focused on addressing BSA/AML deficiencies, while 17 percent addressed BSA as either a focus or within some provision of the action. By 2005, these levels had increased to 19 percent and 49 percent, respectively. This is not surprising given the increased focus on BSA/AML since enactment of the USA PATRIOT Act, a number of high profile failures by large institutions to comply with the statutes and the resultant inquiries, and the statutory requirement to take formal enforcement actions for programmatic violations of implementing regulations.

Enforcement Actions Issued

by the Federal Reserve System, 2000-05 |

||||

Reason |

Cease and |

Written |

||

|

Number |

% of |

Number |

% of |

Traditional safety and soundness |

6 |

12.25 |

70 |

55.56 |

Bank Secrecy Act/Anti-Money Laundering |

28 |

57.14 |

31 |

24.60 |

Noncompliance with enforcement action or commitment |

5 |

10.20 |

0 |

|

Illegal bank holding company |

3 |

6.12 |

1 |

0.79 |

Internal controls, audit, risk management weaknesses |

0 |

|

10 |

7.94 |

All other (less than 5% each) |

7 |

14.29 |

14 |

11.11 |

Total |

49 |

100 |

126 |

100 |

The impact of the increased focus on compliance is also apparent in the practices surrounding civil money penalty assessments. As shown in the chart above, the number of civil money penalty assessments against institutions has been on a generally increasing trend since 1999. Over that same period, the amount of assessments has varied substantially.4 However, it is noteworthy that the FRS has a tendency to dominate the amount of assessments. In only two years did the FRS's share of the dollar amount of assessments fall short of its share of the number of assessments. FRS assessments are largely tied to its responsibilities for supervising bank holding companies and foreign banking organizations in addition to state member banks.

Digging deeper: Civil money penalty reveals dichotomy

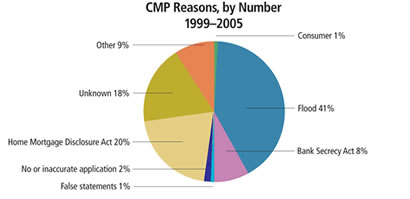

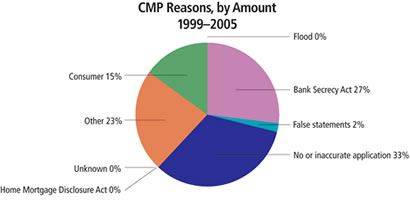

Data from 1999 through 2005 reveal an interesting dichotomy between the reason for assessments when compared by number of assessments and by dollar amount as shown in the pie charts below.

Note: Assessments are listed with an unknown reason either because there is no link to the actual document or because the document was unclear about the reason for the assessment. Based on their size, the bulk of these penalties appear to be related to violations of either the Flood Disaster Protection Act or the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act.

Sources: Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., Federal Reserve System, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Office of Thrift Supervision

While the number of assessments is clearly dominated by those resulting from violations of the Flood Disaster Protection Act (FDPA) and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, the amount of penalties is dominated by those related to failing to file required applications or filing inaccurate applications and BSA/AML violations. A single action related to violations of consumer protection statutes accounts for the entire amount of the assessments that is attributed to consumer protection weaknesses.

The results shown in the pie charts are generally consistent with the conclusions related to the use of cease and desist orders rather than written agreements. Just as the harsher cease and desist order is used for matters that involve elements of dishonesty or high profile areas such as BSA/AML compliance, so too are the largest civil money assessments in these areas. One should not be surprised that these types of activities (failing to file required applications, filing applications that are incomplete or making false statements), while few in number, result in harsh sanctions given the element of dishonesty involved in such cases. With respect to BSA/AML and consumer protection actions, the potential and at times actual involvement of other agencies, including the Department of Justice and state attorneys general, may tend to raise the profile, and hence the amount of penalties, associated with these areas.

The increasing number of penalties, yet small dollar amount of those penalties related to violations of the FDPA, can also be traced to statutory requirements implemented after the significant flooding of the Mississippi River area in 1993. The 1994 amendments to the FDPA require that supervisors assess penalties of up to $350 per violation against institutions that engage in a pattern or practice of noncompliance with the statute's requirements. The statutory limit on the amount of penalties drives the low assessment amount. The supervisors' increased focus on this area during consumer compliance examinations after significant flooding in the Upper Midwest in 1997 revealed continued compliance deficiencies and is likely responsible for the increased number of flood-related assessments. The 2005 hurricanes and aftermath have again focused attention on flood insurance- related compliance issues.

Actions against institution-affiliated parties

Turning to actions against institution-affiliated parties, a search of the supervisors' databases reveals that the vast majority of enforcement actions are against those individuals who are actively involved in ownership or day-to-day control of banking or thrift institutions. A manual scanning of the supervisors' databases from 1995 forward revealed only 10 enforcement actions against entities that were easily identifiable as institution-affiliated parties not subject to action prior to FIRREA. Five of these enforcement actions involved accounting firms, while three involved legal firms. In most of these cases, orders outlining future standards of practice accompanied agreements or orders to pay restitution either to the entity being advised or to the receiver for that entity. By far the largest order was $85 million paid by Ernst & Young in connection with the failure of Superior Bank FSB.

Conclusion and implications for the future

Trends in enforcement activity since 1989 reveal a number of overriding conclusions, all of which support the conclusion that supervisors have acted with restraint when using the substantial powers granted under FIRREA and FDICIA and not in an "arbitrary, Draconian and inflexible" manner:

- Not surprisingly, the factors that tend to lead to less than satisfactory ratings appear to be closely correlated to those leading to formal enforcement actions. As industry conditions improve or deteriorate, the number of enforcement actions declines or increases accordingly.

- Supervisors are sensitive to the implications of greater transparency in enforcement activity. More severe forms of enforcement actions, including higher monetary penalties, are generally tied to enforcement actions that result from noncompliance with high profile statutes such as BSA.

- Statutory requirements do result in assessment of penalties as demonstrated by the number of actions related to BSA and the civil money penalty assessments related to violations of the FDPA.

- Supervisors have exercised restraint in using the "super powers" given to them in FIRREA and FDICIA. Multimillion-dollar civil money penalties are rare in general and are even more infrequently assessed against individuals not involved in ownership or control of financial institutions.

Since formal enforcement actions have been made public, the highest penalties and most severe actions have been reserved for those organizations and individuals that engage in activities carrying an aspect of dishonesty or unlawful conduct. Attempts to circumvent or evade application requirements, filing misleading or incomplete applications or financial statements, or making false statements to examiners tend to result not only in cease and desist actions but also substantial civil money penalties.

Whether these trends will hold in the future remains to be seen. Since the supervisors were given these enhanced powers, there has not been a widespread or sustained banking crisis. Anecdotally, there is evidence that the fear of harsh enforcement action has discouraged institutions from engaging in particular activities, such as subprime and payday lending and providing banking services to money service businesses. Whether the trend away from using the most severe enforcement actions primarily to address safety and soundness concerns would continue in the event of a serious deterioration in banking conditions is uncertain given the lack of a meaningful downturn since formal enforcement actions became publicly available. It is conceivable that if a banking crisis were to emerge, fear of being perceived as lenient could cause the financial institution supervisors to reemphasize the cease and desist order as a tool to address traditional safety and soundness issues. In that case, it is possible, although by no means certain, that enforcement efforts could exacerbate any crisis. To what extent remains to be seen. Stay tuned.

Endnotes

1 For purposes of this article, the term "financial institutions" refers to commercial banks and thrifts, and the term "bank" refers to commercial banks only.

2 See speech by Assistant Secretary for Financial Institutions Richard S. Carnell, U.S. Department of the Treasury, at the Brookings Institute Conference on FDICIA (December 19, 1996) for some initial responses to FDICIA.

3 Temporary cease and desist orders can be issued without an administrative hearing under limited circumstances. While these enforcement actions are effective on issuance, the institution may challenge the action in federal court after the action has been issued.

4 The FRS and OCC list the amount of civil money penalty assessments in each year since 1989; however, the FDIC and OTS Web sites do not show institutional civil money penalty data prior to 1994 and 1996, respectively. (The FDIC Web site does include assessments related to late or inaccurate filing of quarterly reports of condition.) It is not known if no actions were issued or if they simply are not included on the Web sites.