To some, it's the business equivalent of an alien invasion—a faceless enemy of local, independent shops.

Franchises. They're he-e-ere.

Not that anyone had to tell you, probably. Franchising has not exactly sneaked up on an unsuspecting public, tapping it on the collective shoulder and yelling,"Boo!" The streetscape is a regular, visible reminder of the growing presence of franchises in most cities.

Not that anyone had to tell you, probably. Franchising has not exactly sneaked up on an unsuspecting public, tapping it on the collective shoulder and yelling,"Boo!" The streetscape is a regular, visible reminder of the growing presence of franchises in most cities.

But it might surprise many to know that franchising runs much deeper in local economies than the fast-food restaurants and retail outlets lining the intersections of busy highways. Though the roots of franchising—as well as its most recognizable branches—continue to be in food and retail markets, the underlying business model has proven applicable and useful to a growing number of business concepts and industry sectors. Where once franchising seemed limited to burger joints and convenience stores, it has broadened to encompass an array of goods and services, targeting businesses as well as retail consumers.

Yet despite its obvious presence in today's economy, franchising is a phenomenon that we know tangibly little about in an economic sense. Government collects virtually no data on the matter; very few academic centers pay any attention to the concept, outside of maybe some entrepreneurial courses. There are private data and other resource organizations that cater to the franchise industry, but they are in business to serve narrow private information needs, not broad public ones. This paucity of data has created something of a vacuum when it comes to understanding the broader growth of franchising, particularly at the state or local level, to say nothing of related economic effects.

So to learn more about franchising in the Ninth District—in a hard-data sense—the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis contracted with FRANdata, a private research and marketing firm that tracks the franchise industry, to provide data on franchises in a five-state region over the past decade.

The data suggest a number of interesting, if not always surprising, results: Franchising in the district is growing, at different rates in different states. More notable, franchising appears to be growing faster than other types of firms in district states. Although one might assume that franchises thrive in large population centers, that isn't always the case in terms of franchise concentration.

Like all businesses, franchises have to compete to stay in business, and historical data show considerable volatility and turnover among franchises. And though community advocates might fear the effects of competition from franchises on local mom-and-pop stores, in fact, a very large majority of franchises are themselves independently owned.

(Because of the proprietary nature of FRANdata's historical information on franchises, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis cannot disclose detailed information about individual franchises. Anecdotes and company-specific information included in these articles have been either gleaned from other sources or approved by FRANdata.)

McFranchise

Franchising is a business concept that was born in the 1940s and took root in the 1950s and '60s because of a broad shift in the U.S. economy from manufacturing to the provision of services. More specifically, it grew by catering to the lifestyle of an increasing number of two-income families that demanded consistency and convenience, according to a report two decades ago by John Naisbitt (author of Megatrends) and the Naisbitt Group.

Naisbitt called franchising the most successful marketing concept ever—a claim that's hard to dispute. The industry grew up, and still rides, on the shoulders of the food service industry. It all started with fast-food chains, but has broadened in almost every direction, with new concepts always in development. Today, ethnic food franchises are among the fastest growing concepts. Sioux Falls, for example, saw two new Mexican restaurant franchises—Qdoba and Puerto Vallarta—come to town earlier this year.

But today franchising reaches well beyond food and is represented in more than 100 business sectors, including health and beauty, automotive, real estate, cleaning and janitorial, tax and legal consulting, sports and fitness, employment, computers, shipping, home construction and repair, children's education and day care, and many more. Franchise concepts range from the seemingly mundane (like signs) to the specialized—some might say inane—such as laser hair removal.

But today franchising reaches well beyond food and is represented in more than 100 business sectors, including health and beauty, automotive, real estate, cleaning and janitorial, tax and legal consulting, sports and fitness, employment, computers, shipping, home construction and repair, children's education and day care, and many more. Franchise concepts range from the seemingly mundane (like signs) to the specialized—some might say inane—such as laser hair removal.

Franchising a business or concept is not that difficult, according to sources, although certain characteristics are good indicators of whether a business might be a good candidate: profitability, definable market niche with broad public appeal, relatively inexpensive to start and easy to operate and, most obviously, easy to duplicate regardless of location. Are you a recovering clutter bug? Maybe you should consider opening a 1-800-GOT-JUNK franchise. But you won't be the first—there are 300 locations in four countries. Six of them are in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

A major reason the franchise model works is that both parties bring something tangible to the table: The franchisee offers fresh capital to expand the brand, as well as managerial leadership, and assumes most of the financial risk. In return, the franchisor provides a proven, branded enterprise—something of a paint-by-numbers business—which eliminates much of the early heavy lifting and risk that would come with building a business from scratch.

Franchising is particularly popular with folks in their 50s looking to net a good return from their financial nest egg, said Chuck Modell, a franchise lawyer for 30 years with the Minneapolis firm Larkin Hoffman Daly & Lindgren Ltd. He also sees a lot of young people just out of college get into franchising—often with some parental backing—as well as successful corporate types who want to get out of the rat race. All of these would-be entrepreneurs have an itch to run a business, but don't feel a rash to grow one from the ground up. Enter franchising.

"You go into business to be on your own, but you're not on your own" with a franchise, said Modell. "You get a lot of assistance on things that could be problematic" for a new business, from site selection to start-up to daily operational matters.

In total, FRANdata estimates there are 3,000 franchise brands in this country and possibly as many as 500 others interested in franchising their business that have not yet done so. More than half of the franchises are characterized by FRANdata as young, or having been franchised for less than 10 years. Last year, 306 companies opened their first franchise, according to FRANdata. The year before, it was 294. Most new concepts—better than 90 percent in the first quarter of 2007—come from new companies, with the remainder coming from existing franchisors looking for growth in new markets.

Although the flexibility and adaptability of the business model is a key element to franchise growth, ultimately the success of a concept depends on it catching on with consumers. Consider them caught, even if reluctantly. Today, it's somewhat fashionable to claim that one doesn't patronize franchises because of their cookie-cutter sameness. But that's something of a Yogi Berra-ism: Nobody goes to those places anymore; they're too crowded. "That's a class statement," Modell said. "Most of America doesn't fit into that (mentality)."

Modell offers an example of why franchises are so popular. He travels occasionally to clients, and he invariably stays at a franchise hotel—maybe not surprisingly, given his legal craft, and the fact that Hilton is one of his major clients. But he's doing it not because he has to, but because he prefers to. "Franchise tells me I know what I'm going to get there." Sure, a boutique hotel or bed-and-breakfast might be more charming or more this or more that.

Modell offers an example of why franchises are so popular. He travels occasionally to clients, and he invariably stays at a franchise hotel—maybe not surprisingly, given his legal craft, and the fact that Hilton is one of his major clients. But he's doing it not because he has to, but because he prefers to. "Franchise tells me I know what I'm going to get there." Sure, a boutique hotel or bed-and-breakfast might be more charming or more this or more that.

But it might also have a bad mattress, or worse. "For most people, we'd rather take the guarantee over the adventure," Modell said.

Be fruitful and franchise

If the visual landscape isn't enough, statistics from FRANdata ought to convince even the hardest skeptic that franchising is a successful business model, almost regardless of location or line of business.

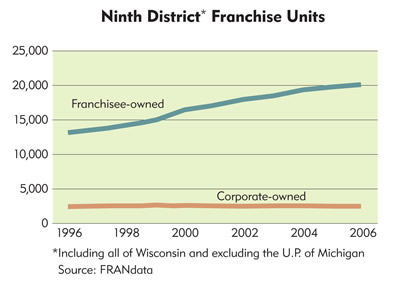

Across the district, the number of franchise units grew by 45 percent from 1996 to 2006 to more than 22,000 franchisee- and corporate-owned establishments (see Chart 1). Minnesota took top growth honors at 50 percent, with South Dakota and Wisconsin close behind. Montana and North Dakota were on the low end of growth, at 27 percent and 25 percent, respectively. (See franchise growth snapshots for five district states.)

Chart 1

Every district state saw a large spike in new franchise units in 1999, 2000 or both. Sources suggest it was fueled by the stock market boom of the 1990s, which created a lot of paper wealth and restless entrepreneur wannabes. The 2001 recession and subsequent stock market decline put an end to the franchise surge (see charts in state snapshots).

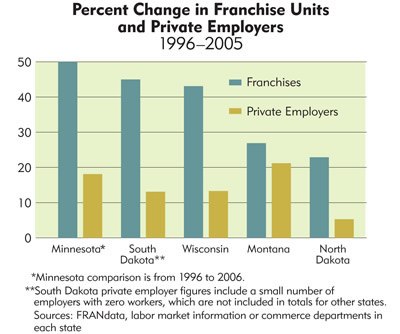

Despite the lull, franchise growth since 1996 has been considerably stronger than growth of all private employers over the same period. Among district states, only in Montana were the two growth rates even in the same ballpark (see Chart 2).

Chart 2

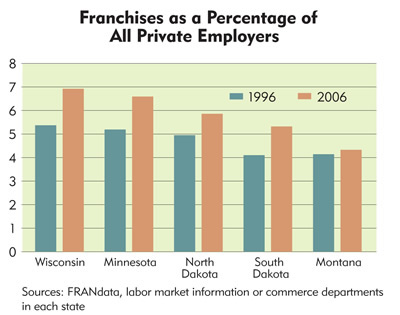

This means that, in any given state, franchises are increasing as a proportion of all firms. But this growth is happening slowly. Although franchises seem ubiquitous, they still account for a comparatively small percentage of employer firms-to say nothing of all firms, including sole proprietors (see Chart 3).

Chart 3

Much of the growth in franchise units comes from existing chains, including a handful of companies that are seeing explosive expansion. Subway, Hot Stuff Foods, Curves for Women and Jani-King have all added hundreds of units across district states just in the past decade.

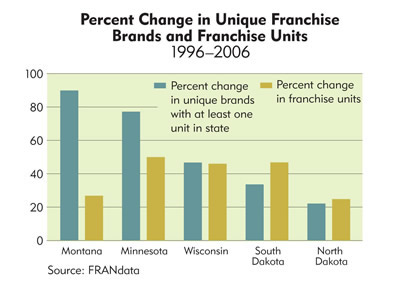

But franchise growth is also being fueled by a steady influx of new concepts in each state. From 1996 to 2006, growth in the number of unique brands in each state was at least as great as franchise-unit growth. In Minnesota and Montana, it was far higher (see Chart 4). But just as the increase in new units slowed after 2000, so has the number of new brands coming to individual states. Between 1996 and 2000, for example, more than 100 unique franchises came to Montana; only about 30 have come since. The trend was similar in the Dakotas. Wisconsin and Minnesota have witnessed more balanced growth of new brands over the study period, but growth has been much more modest over the past few years in these two states as well.

Chart 4

Still, given the growth of franchises, as well as the breadth of franchise concepts—including some in-home businesses—it might seem impossible that certain areas are bereft of franchises altogether. Yet, according to FRANdata figures, 21 counties in the Dakotas and Montana tallied a goose egg in franchises.

A street corner near you?

The location and concentration of franchises might best be called a bit irregular, at least if you look past first impressions. Logically, one might conclude that there are more franchises in metros and other larger cities than in less densely populated areas. That's certainly true in terms of absolute numbers. But if you weight franchise concentration on a population basis, that muddies the picture considerably, at least according to available data.

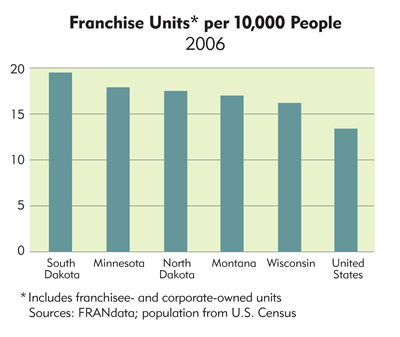

For example, among district states, there doesn't appear to be any obvious pattern or rank on a per capita basis: South Dakota has the highest concentration of franchise units per 10,000 people; Wisconsin, the lowest. All district states are relatively similar, yet all of them—sparsely populated, comparatively—are well above the U.S. average in terms of franchise saturation (see Chart 5).

Chart 5

Even within states, there appears to be no unbreakable link to population, according to county-level franchise counts from FRANdata. Because of methodological differences in state- and county-based figures, county-level data tend to undercount franchises in relation to statewide figures (see methodology). Therefore, results should be considered preliminary and tentative.

With that caveat, available county data suggest that population cannot predict franchise concentrations. For example, the seven counties encompassing the Twin Cities and their suburbs hold the lion's share of franchised businesses. But weighted for population, FRANdata county figures show that the seven-county Twin Cities region has a lower number of franchises per 10,000 population than the rest of the state and by a fairly large margin (roughly 20 percent in terms of population per franchise). Among these seven metro counties, the two most populous (Ramsey and Hennepin, home to St. Paul and Minneapolis) have the lowest concentrations of franchises.

The same relationship exists in South Dakota's two metro counties; both have a lower concentration of population-adjusted franchises than the rest of the state. The opposite is true, however, in North Dakota's three metro counties, where each has a higher number of franchises per 10,000 people compared to all other counties in the state.

Superficially, at least, there appears to be some relationship between franchise concentrations and population growth. That would appear to be the case in North Dakota; most of the population growth is occurring in the three metro counties. Five counties in Montana have populations over 75,000; four have a higher concentration of franchises compared to the rest of the state. The other one—Cascade—has significantly fewer franchises per capita compared to the other four large counties and the statewide average. Cascade is also home to the Great Falls metro area, which has experienced stagnant population growth over the past decade.

The connection with population growth can be seen in small counties as well. For example, consider the small rural Wisconsin counties of Lincoln, Oneida and Washburn, as well as Cass and Crow Wing counties in Minnesota and Lawrence and Meade counties in South Dakota: All have high franchise per capita numbers, and each also happens to be seeing strong, natural amenity-based tourism and population growth.

But among the hundreds of other counties in the district, there are small and large counties with comparatively higher and lower concentrations of franchises than one might expect if there were a clear link to population. Without a deeper investigation of local economic trends and other factors, the bulk of district counties defy simple explanation or generalization.

More local than you think

With all the national franchise brands in your face, it's easy to overlook the fact that most franchise businesses are owned by local, independent operators.

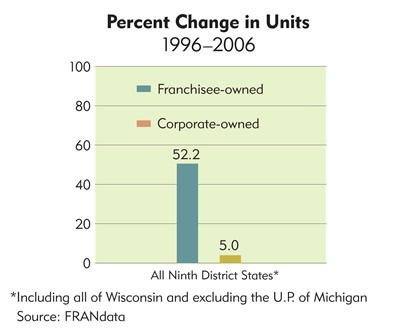

Today, independent franchisees own almost 90 percent of franchise units in the Ninth District, and the trend is toward even greater imbalance. Since 1996, the number of independently owned franchise units in the district has grown 52 percent; for corporate-owned units, growth was just 5 percent (see Chart 6). In Wisconsin, the number of corporate-owned units actually declined over this period.

Chart 6

The trend toward more independent franchisees has gradually gained momentum over time as cash-strapped corporate chains realized they could expand their brands and continue to increase revenue by using other people's money to open new units. Then a funny thing happened on the way to the drive-through: Independently owned franchises also proved they could earn higher profits than corporate-owned units.

The biggest reason is pretty simple, really. A corporate-owned unit suffers from what economists call a principal-agent problem, which concerns the alignment of the self-interests of the manager (the agent) with the profit motives of the owner (the principal). A store manager has less invested in the business and therefore has less concern for profits than the off-in-the-distance corporation. An independent franchisee solves that principal-agent problem because he is both manager and owner—as Modell said, "He owns it, he cares about it ... if it's 8:30 on Friday night and he wants to close, he doesn't." Deciding to close might be easier for a young corporate-hired manager with a date on Friday night.

Besides solving the managerial dilemma, franchising has other advantages. For one, individuals seeking to own and operate a franchise also tend to be skilled and motivated individuals, according to Hachemi Aliouche, a senior research fellow at the William Rosenberg International Center of Franchising at the University of New Hampshire. Maybe more important, "franchisees also know the local market and the local bureaucracy," said Aliouche.

Conventional wisdom and empirical research have long emphasized the importance of knowing your local market, and the notion holds true in franchising as well. A 2004 study in Management Science of pizzeria survival in Texas found that "an owner's experience in the local area is just as important within franchised chains as outside them. ... Even in franchised industries—where codification and standardization are at the core of competitive advantage—and even in an era of inexpensive transportation and almost costless global communication ... (local market knowledge) still appears to play a primary role in business success."

Add it all up—comparatively low capital start-up costs, shared risk and knowledgeable and highly skilled local owners—"these are all tremendous benefits" of the franchisee model, Aliouche said. Franchisors are adjusting accordingly. Rather than open new corporate-owned stores, parent companies are often using available capital to help independent franchisees finance a new unit.

Turnover, not the apple kind

Despite their ubiquity in many communities, franchises still must compete for business, and not all of them are able to do it successfully. Young as well as mature franchises succumb to competitive pressure. Such franchising stalwarts as Burger King, Hardee's and Country Kitchen all have seen their total units in the district as of 2006 decline from peak years, though each still has a significant presence in one or more district states.

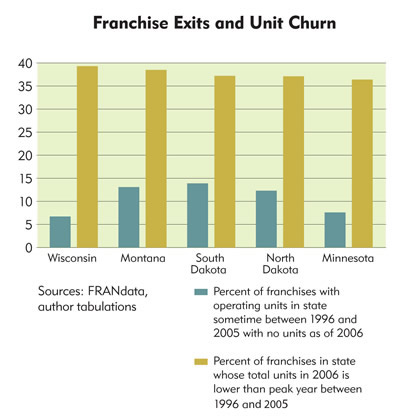

The franchise industry overall appears to go through a fair amount of unit churn over time: Some brands grow quickly, others manage to hold their own and still others lose ground. According to unit counts of unique franchises from FRANdata, by state and over the past decade, a fairly consistent proportion of franchises—estimated at between 36 percent and 39 percent for each district state—had fewer total units in 2006 than in any peak year between 1996 and 2005 (see Chart 7).

Chart 7

It's not uncommon for a franchised brand to exit a state altogether after establishing a beachhead; for whatever reason, the concept doesn't catch on. For all brands that had at least one unit in a district state between 1996 and 2005, roughly one in 10 had no presence in that district state in 2006. The rate of exit was also noticeably higher in the Dakotas and Montana (all around 13 percent) than in Minnesota and Wisconsin (around 7 percent). Usually, this occurs among smaller franchises with one to several units in a state.

It's difficult to say exactly how that churn rate compares to nonfranchise businesses in terms of survival. Data on survival rates of all businesses are not very good to start with, particularly below a macro level that might allow comparisons of similar types of firms in the same industry or sector. Bureau of Labor Statistics research in 2005 and 2006 estimated survival of new firms at 66 percent after two years, gradually receding to about one-third after seven years of operation.

At first blush, franchise turnover would appear to outperform that level. However, FRANdata records do not track individual establishments, and as such, the survival rate or longevity of individual franchise units cannot be determined. Franchise sources claim that franchise survival is naturally higher almost by design because franchisors provide new recruits with a formulaic business that has been proven to work elsewhere.

That seems to make sense, but no scientifically valid study could be found to buttress that argument, and in general little empirical research exists in the public domain that would clarify this matter of firm survival. What data are available suggest that survival rates are fairly similar for franchise and nonfranchise firms in the same sector. For example, H. G. Parsa, from Ohio State University, looked at restaurant survival rates in the Columbus, Ohio, region and found that franchise chains enjoyed a slightly higher survival rate than independent restaurants (43 percent versus 39 percent).

A decade ago, Timothy Bates of Wayne State University analyzed survival patterns among franchisee firms and establishments that began operation in 1986 and 1987. His results suggest that franchising is less of a slam-dunk than it might initially appear. He found that most of the young franchisee units were not owned by brand new firms or entrepreneurs, but by established franchisees who owned multiple units—a trend that has been accelerating since this study's completion, according to the International Franchise Association and FRANdata.

"Among the true newcomers (to franchising), survival rates are low; among the entrenched multi-establishment franchisees, survival rates were high," Bates concluded, adding that he found no support "for the hypothesis that one's initial foray into self-employment can be made safe by mere purchase of a franchise."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.