When there is a medical emergency, everyone knows that you call 911. But what if the emergency concerns the medical organization itself? Who do you call?

For rural hospitals, many of which have been gasping financially for years, the answer has been the federal Critical Access Hospital (CAH) program. This Medicare-based program gives rural hospitals the organizational equivalent of CPR because it purposefully pays rural hospitals more to care for Medicare patients than urban institutions receive. These higher reimbursement rates have improved profit margins and offered the possibility of upgrading long-neglected facilities.

But despite its popularity, the program is not without debate or controversy. Until last year, loopholes in eligibility let states virtually rubber-stamp hospitals into the federally funded program. Predictably, participation in the program surged in the past decade, particularly in Ninth District states. The program's original intent was to retain hospital access in isolated rural areas; what's in place now is a web of CAHs, many of them within a short drive from another hospital, CAH or otherwise.

And though the program has been essential for many rural hospitals, the CAH program is not financially lucrative enough to overcome the larger demographic trends lambasting many rural hospitals. As a result, the program may merely be keeping some hospitals on life support, consuming finite health care resources to support an inefficient arrangement of services.

Bleeding red ink

Rural hospitals have been under financial distress for some time. Across the country, the number of rural hospitals dropped from about 2,700 in 1984 to 2,100 in 2003, according to the American Hospital Association. The number of urban hospitals also dropped during this period, though by a smaller amount, and has recently rebounded slightly, thanks to growth in suburban areas.

The main reason for this hospital slump in rural areas is pretty simple: The patient base is small and stagnant, even declining in some places, and locals are more willing to drive to newer hospitals and specialty care centers elsewhere. Over time, elderly Medicare patients have come to dominate the rural patient base.

Though this federal health care program for the elderly offers a steady stream of revenue (older folks tend to consume a lot of health care), Medicare's reimbursement rates have been getting stingier, while overall Medicare treatment expenses have been going up. This has put the operating margins of many rural hospitals in the red; on average they lose money on every patient they treat. (See previous discussion on hospital operating margins and reimbursement rates of Medicare and other payers in the January fedgazette.)

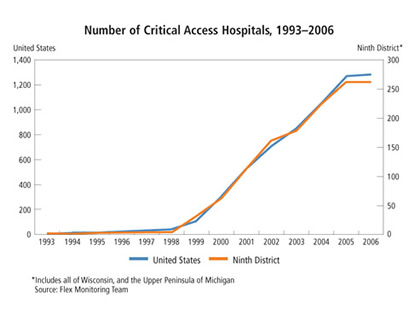

Enter the CAH program. It started as a pilot program (by another name) in Montana in 1988 that sought to retain health care access in rural areas by offering higher payments for elderly patients than Medicare's prospective payment system (PPS). A year later, Congress authorized a second, similar program. South Dakota's Faulk County Memorial Hospital is the oldest participant in either pilot program that is still operating, having joined in 1993. Over the next few years, Faulk was joined by about 40 other hospitals, including another seven in South Dakota.

The program changed in a big way with the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. This law formed the Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility Program, which combined the two earlier pilots and created a new type of hospital called a critical access hospital that would receive higher reimbursements from Medicare compared to PPS.

Without diving headfirst into the quagmire of Medicare finance, the difference between CAH and PPS reimbursement is fundamental: PPS is based on complicated formulas that calculate an average cost for various treatments. Hospitals are reimbursed at the established PPS level, regardless of the actual treatment expense tallied by the hospital. Though there are quirks that raise Medicare payments under certain conditions, in general rural hospitals tend to have meager or negative PPS margins because small patient loads, older facilities and other factors elevate their average cost per patient.

The CAH program, on the other hand, reimburses a participating rural hospital 101 percent of its cost for treating Medicare patients. So it doesn't take a math whiz to figure out which payment plan is a better deal for rural hospitals. Eligibility guidelines are not particularly arduous. The most important eligibility criterion is for a hospital to be 35 miles away from another hospital and have no more than 25 acute-care beds. Another seemingly innocuous provision gave states the authority to declare hospitals "necessary providers" and thus CAH-eligible.

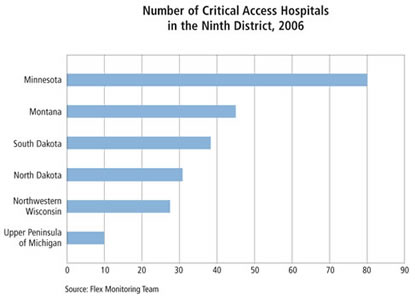

With expanded participation guidelines, hospital enrollment in the CAH program exploded. In 1999, 76 hospitals joined the program, including 26 in the district and 15 in Montana alone. By the end of 2005, the program comprised almost 1,300 hospitals nationwide and 231 in the Ninth District (287 if all of Michigan and Wisconsin, much of which lie outside district borders, are included).

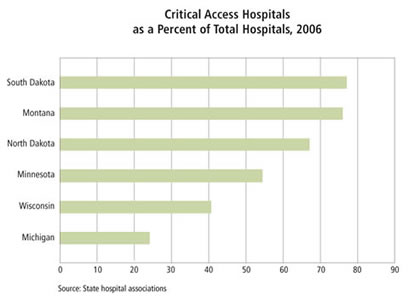

Rural states clearly benefit from the CAH program. Almost half of all CAHs are located in 17 states, mostly in Midwest and Great Plains states (see map). In rural states like Montana and the Dakotas, the great majority of hospitals are CAHs (see chart).

A big factor in the flood of new critical access hospitals was the ability of states to declare certain hospitals as medically necessary, which exempts them from the 35-mile-radius requirement. A study by RTI International, a nonprofit research firm, found that of the thousand or so hospitals that had converted to CAH status by 2004, 60 percent had done so by state order. In a similar vein, a 2005 report by MedPAC, a federal advisory agency on Medicare, pointed out that "states have set the criteria so that most (and in some cases, all) of their small rural hospitals are declared necessary providers, and therefore are eligible to be helped by the CAH program."

Congress closed the state loophole Jan. 1, 2006. The MedPAC report said that consultants working with CAHs "noted a flurry of activity among hospitals that are deciding whether to convert to CAH status before the (deadline)." Today, more than 80 percent of CAHs nationwide are closer than the 35-mile guideline; one in six is 15 or fewer miles from another hospital, and some are as close as five miles. Very little future growth is likely in CAHs, because virtually all facilities eligible under federal guidelines are already in the program.

In 2003, the state of Wisconsin helped St. Mary's Hospital in Superior grab CAH designation. An analysis by the state Department of Health and Family Services argued that CAH status was necessary for St. Mary's because a "tenuous financial condition ... jeopardizes its continued operation and places it in imminent danger of closing unless the hospital can be designated as a CAH and receive cost-based reimbursement. The closure of St. Mary's would reduce Douglas County residents' accessibility to acute care."

Well, sort of. The city of Superior is just across the state border from Duluth, Minn., which means St. Mary's Hospital is only about nine miles from St. Luke's Hospital and the Miller Dwan Medical Center, the latter of which is a specialty care hospital and part of the same health organization (St. Mary's/Duluth Clinic Health System) as the Superior hospital.

Every district state likely has similar instances of relatively short drives between CAHs and other acute care facilities. Virtually all rural hospitals (80 of 82) in Minnesota are CAHs, including a cluster of them in sparsely populated western portions of the state (see map).

The healing touch

Regardless of questionable enrollment practices, rural hospitals can't be blamed for taking advantage of an opportunity. There's no mistaking why hospitals want to be in the program, according to both industry sources and empirical research: more money for the same work.

George Quinn, senior vice president of finance for the Wisconsin Hospital Association (WHA), said CAH designation can add $300,000 to $600,000 a year to hospital revenue, and "that all flows right to the bottom line."

Numerous studies back up that figure. "By nearly all accounts the financial condition of converters has improved," mostly because of better reimbursements, according to a November 2006 report by researchers at the University of North Carolina, part of the Flex Monitoring Team, a consortium of three research centers (including the University of Minnesota) that tracks CAH program performance.

The program has a positive, almost immediate effect on the financial health of most rural hospitals. A 2004 working paper from the Rural Health Research Center at the University of Minnesota looked at early converters to CAH status. Those converting in 1999 saw profit margins rise about 5 percentage points in the first year (on average, from -2.5 to 2.3 percent) and further still the second year (to 3.7 percent). That shift was the result of a 36 percent increase in total Medicare payments to these hospitals, or about a half-million dollars.

MedPAC, in its 2005 study, reported that hospitals converting to CAH status "dramatically increased" their Medicare revenue, which helped to improve overall profit margins from -1.2 percent in 1998 to 2.2 percent in 2003. It estimated that Medicare's cost-based payments to CAHs in 2006 would be about $1.3 billion, or about 30 percent higher than the comparable PPS payment rates for the same services.

Additional research by Jeff Stensland, a senior analyst with MedPAC, looked at two groups of hospitals from 1998 to 2003, one of them CAH-designated and the other not. The CAHs saw total hospital revenue grow by almost 10 percent annually, compared to 3.3 percent for the non-CAHs, a fact that Stensland said "is almost all due" to the CAH program.

With wider operating margins, many rural hospitals "are remodeling their facilities or even building new facilities," Stensland noted. The University of Minnesota study—which Stensland also helped author—similarly found that hospitals converting in 1999 increased capital expenditures significantly just two years later.

Sources in the district echoed that phenomenon. Gregg Redfield, vice president of finance for the Minnesota Hospital Association, said the program "has enabled facilities to do projects they wouldn't have been able to do otherwise."

Without the CAH program, Montana hospitals "couldn't even think" about building upgrades, according to Jim Ahrens, president of the state hospital association. Rural hospitals there have seen a burst of financing activity, the precursor to capital projects. Most of them get financing assistance from the Montana Facility Finance Authority, an arm of the state Department of Commerce created to help health care facilities finance capital building and equipment projects.

The agency recently closed on a $7 million deal to help a hospital in Hamilton expand its emergency room; it approved a $10 million package for upgrades at joint facilities in Poplar and Wolf Point, which haven't seen upgrades since their construction, according to Michelle Barstad, MFFA executive director. Her office is also working on a $20 million to $30 million deal for a major hospital remodeling and addition in Ronan and $10 million in financing to replace the hospital in Red Lodge. Hospital officials in Livingston are also reportedly considering a major upgrade, and possibly a full replacement, of the facility there.

A 2005 study on rural hospital replacement by Stroudwater Associates and the Red Capital Group looked at 20 CAHs that had recently replaced older facilities; nine of them were in district states. The report found that admissions and total patient days increased, total staffing actually went down on an adjusted unit measure and earnings before various accounting charge-offs (so-called EBIDTA) went up significantly. The report concluded that "rural communities that built new CAH hospitals not only experienced increased market share, but also report enhanced clinical performance, improved workforce recruitment and retention, and improved quality performance."

I'm not dead, yet

To be sure, the CAH program is not a cure-all. Though it is widely credited for halting the closure of rural hospitals, a half-dozen rural hospitals have nonetheless closed in Minnesota since 2000, according to state records.

Over the past decade, a similar number have closed in North Dakota, according to industry sources there. "Critical access has had very little impact," according to Arnold "Chip" Thomas, president of the North Dakota Healthcare Association (NDHA). "The performance of North Dakota (critical access) hospitals in no way mirrors neighboring states." Mountrail County Medical Center in Stanley, N.D., was one of the hospitals in the Stroudwater study; it was also one of the first hospitals in the state to convert to CAH status. It converted in 1999 in conjunction with other efforts to help fund a new hospital, which was completed in 2003. "It was a no-brainer to go critical access. It was the way to go and certainly helped," said Mitch Leupp, the hospital's CEO, in a phone interview.

Medicare and its 101 percent cost reimbursement cover 55 percent to 65 percent of the hospital's inpatient business in a given year, Leupp said via e-mail. The remaining patient mix came from Medicaid (the government health care program for the poor), workers' compensation, private insurers and other private payers. Reimbursements from many of those funding sources fall below the hospital's costs to provide services.

"Imagine running any business on 1 percent profit—retroactively reimbursed—and have the other payers for the most part paying you less than your cost. It doesn't take long to figure out that this doesn't work very well," said Leupp. Not surprisingly, MCMC lost money in the past fiscal year, although it was one of the smaller losses of late. But the current fiscal year "is looking worse," Leupp said.

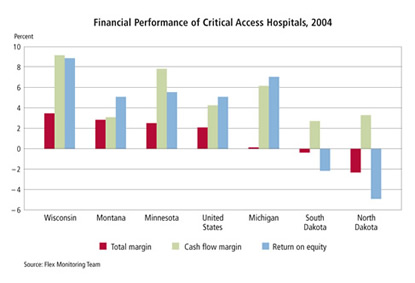

MCMC is more the rule than the exception in North Dakota: Leupp estimated that 60 percent to 70 percent of hospitals are in the red—a situation not found in any of the surrounding states, according to both Leupp and Thomas. A November 2006 study by the Flex Monitoring Team confirms that North Dakota CAHs perform notably worse than those in other district states (see chart).

NDHA even hired a consultant to find out why this was the case. The answer stems in part from the integration of hospitals into larger health care networks, said Karen Haskins, NDHA vice president, via e-mail. Unlike in most states, hospitals in North Dakota tend to own and manage clinics, nursing homes, home health agencies and other pieces of the health care continuum. "Because of this, our CAHs have a different set of issues with their operating margins," Haskins said.

In essence, Medicare revenue for CAHs in North Dakota "is as good as other states," Haskins said. But as part of a larger health care network, that revenue is not always retained by the hospital. "Some of their (hospitals') revenue may be needed to keep the other systems running," Haskins said. "Our study did indicate this may cause more difficulty with a positive margin."

Ultimately, the CAH program is spitting into a strong health care headwind, and not just in North Dakota. As one hospital official told Ahrens, from the Montana Hospital Association, "The good news is that critical access gives you 101 percent of cost. The bad news is that it gives you 101 percent of cost." In other words, the program helps keep the doors open, but it doesn't provide enough margin in a health care environment that demands regular investment in new facilities, equipment and information technology.

As Mountrail's experience shows, the real problem for most rural hospitals rests outside its Medicare patient base: The proportion of privately insured patients (who are typically more profitable) is stagnant or declining, and Medicaid reimbursements typically fall well below a hospital's costs to treat low-income patients. To this end, the CAH program can provide just enough aid to keep hospitals alive, but not necessarily enough to get them back on their financial feet. Given the rush of state designations, the program may now be propping up a health care arrangement that might generously be described as inefficient.

Silver lining, without the silver

Arguably, the CAH program has gone overboard in its original goal to retain rural access to acute care. By doing so, the benefits of proximity likely get outweighed by the costs of inefficiency and higher health care spending.

Certainly, the health care spending funneled through the CAH program is beneficial—indeed, life-saving—for the patients and hospitals on the receiving end, as well as the local community. Losing a hospital can be a crushing blow to a city, in part because the hospital is often the largest and best-paying employer in town.

And in the scheme of things, the money spent on CAHs is a pittance. Nationwide the program involves less than one-quarter of hospitals, but these hospitals cumulatively treat less than 5 percent of patients, and the subsidy payments to rural hospitals adds less than one-half of 1 percent to total Medicare spending.

Still, with the large majority CAHs just 35 miles or closer to another hospital, these low-volume hospitals "are receiving cost-based reimbursements when they are not critical for beneficiaries' access to care," said the MedPAC report. It's certainly more convenient for area residents to receive care locally, but this represents a fundamental shift in the program's motive from isolated access to local entitlement.

The CAH program's cost-based reimbursement model also has ongoing ramifications for taxpayers because it does not reward efficiency and cost reduction. Indeed, financial incentives are aligned with the opposite effect. Several sources, including Leupp, pointed out that a hospital cannot allow costs to spiral unchecked, mostly because Medicare doesn't cover all patients, and losses on non-Medicare patients would balloon further.

But there is some evidence that costs are rising faster at CAHs. MedPAC expressed concern over the reduced incentive to control costs among CAHs after finding that costs per unit of service at CAHs rose 53 percent from 1998 to 2003, while costs in a comparison group of hospitals grew by 37 percent over the same period.

Hospital officials are also shifting their business models—wisely—to take financial advantage of the opportunities afforded by the CAH program on behalf of patients and the local community. The University of Minnesota study, for example, said it expected hospital margins"to grow further as CAHs adjust their operations to maximize their profitability given their new Medicare payment structure."

The RTI International study looked at Medicare cost reports and claims data from 1996 to 2004 for CAHs as well as a group of near-eligible hospitals that continued being reimbursed under PPS. The study found that revenues and profits per patient rose faster among CAHs, as did the number of employees, annual average salaries and capital expenditures. This is certainly good news for CAHs and their patients, but the report said that cost-based reimbursement "has led to an increase in the intensity of services provided ... and contributed to the growth in Medicare spending."

As with most public policy, whether the CAH program is an effective antidote for what ails rural America depends on the social and health care disease in question. Without it, many rural hospitals would be in much worse shape. But, as even Leupp cautioned, "It is not a silver bullet."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.