The authors thank Kathy Rolfe and Joan Gieseke for excellent editorial assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System.

Editor’s note: This essay is based on the authors’ paper, “Modern Macroeconomics in Practice: How Theory Is Shaping Policy,” published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 20, No. 4, Fall 2006.

Over the last three decades, macroeconomic theory and the practice of macroeconomics by economists have changed significantly—for the better. Macroeconomics is now firmly grounded in the principles of economic theory. These advances have not been restricted to the ivory tower. Over the last several decades, the United States and other countries have undertaken a variety of policy changes that are precisely what macroeconomic theory of the last 30 years suggests.

Over the last three decades, macroeconomic theory and the practice of macroeconomics by economists have changed significantly—for the better. Macroeconomics is now firmly grounded in the principles of economic theory. These advances have not been restricted to the ivory tower. Over the last several decades, the United States and other countries have undertaken a variety of policy changes that are precisely what macroeconomic theory of the last 30 years suggests.

The evidence that these theoretical advances have had a significant effect on the practice of policy is often hard to see for policymakers and advisers who are involved in the hurly-burly of day-to-day policymaking, but easy to see if one steps back and takes a longer-term perspective. Examples of the effects of theory on the practice of policy include increased central bank independence and adoption of inflation targeting and other rules to guide monetary policy, which is the primary focus of this essay. However, examples also include increased reliance on consumption and labor taxes instead of capital income taxes and increased awareness of the costs of policies that distort labor markets.

Before we begin our exploration into the effect of theory on policy, we would like to introduce a metaphor that may help readers frame our discussion, namely, the relationship between an architect and an engineer. Of course, we don’t profess expertise in either of these careers, and so we beg the forbearance of any architects or engineers in the reading audience, but for the sake of our discussion, we would describe architects as those who create a project in broad terms and engineers as those who make those plans real. Architects design in theory; engineers build in practice. Most often, if not always, the theoretical design is tweaked by the engineer to account for unexpected or unintended outcomes, but in the end, the final product greatly resembles the architect’s initial plan. Without the architect’s guiding idea, the engineer is directionless; without the engineer’s applied skills, the architect’s idea lies dormant.

Before we begin our exploration into the effect of theory on policy, we would like to introduce a metaphor that may help readers frame our discussion, namely, the relationship between an architect and an engineer. Of course, we don’t profess expertise in either of these careers, and so we beg the forbearance of any architects or engineers in the reading audience, but for the sake of our discussion, we would describe architects as those who create a project in broad terms and engineers as those who make those plans real. Architects design in theory; engineers build in practice. Most often, if not always, the theoretical design is tweaked by the engineer to account for unexpected or unintended outcomes, but in the end, the final product greatly resembles the architect’s initial plan. Without the architect’s guiding idea, the engineer is directionless; without the engineer’s applied skills, the architect’s idea lies dormant.

So it is with economics. Without the guiding discipline and structure that theory brings, policy has no footing, no direction save the short-term whims of policymakers buffeted by untested assumptions and political demands. Imagine a house built without blueprints by workers with different ideas about how the house should look, and you have a rough approximation of policy made without theory.

To begin, then, we introduce three key developments in academic macroeconomics that have laid out the architecture of modern macroeconomic policy analysis: the Lucas critique of policy evaluation due to Lucas (1976), the time inconsistency critique of discretionary policy due to Kydland and Prescott (1977), and the development of quantitative dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models following Kydland and Prescott (1982).1 Lucas argued that economic theory implies that preferences and technology are invariant to the rule describing policy but that decision rules describing private agents’ behavior are not. In a series of graphic examples, he shows that then-standard policy analyses which presumed invariance of decision rules led to dramatically undesirable policy prescriptions. Kydland and Prescott argue that a regime in which policymakers set state-contingent rules once and for all is better than a discretionary regime in which policymakers sequentially choose policy optimally given their current situation.

The practical effect of the Lucas critique is that both academic and policy-oriented macroeconomists now take policy analyses seriously only if they are based on quantitative general equilibrium models in which the parameters of preferences and technologies are reasonably argued to be invariant to policy. The time inconsistency critique has been a major influence on the practice of central banking and fiscal policymaking over the last 30 years.

The quantitative general equilibrium models that were developed in response to the Lucas critique have become increasingly sophisticated over time, including models with financial market imperfections, sticky prices and other monetary nonneutralities, imperfect competition, incomplete markets, and other frictions. (See Cooley, 1995.) We think of the developers of these quantitative models as the engineers who have applied the vision of the architects, Kydland, Lucas, and Prescott. After years of quantitative study, these engineers deduced four robust properties of optimal monetary and fiscal policies under commitment:

-

Monetary policy should be conducted so as to keep nominal interest

rates and inflation rates low.

-

Tax rates on labor and consumption should be roughly constant over time.

-

Capital income taxes should be roughly zero.

- Returns on debt and taxes on assets should fluctuate to provide insurance against adverse shocks.

Macroeconomists have also been profitably applying the basic tools of general equilibrium theory, computational techniques, and a deep understanding of key features of the data to a wide area of phenomena outside of narrowly defined macroeconomics. These include income differences across countries, fertility behavior across time and countries, the dynamics of the size distribution of firms, and the efficiency costs of the welfare state. A good illustration of this kind of work is the study of differences in labor market performance between the United States and Europe. Although work of this kind has not yet directly affected policy, it will once its policy lessons, carefully grounded in theory and data analysis, are clearly communicated to policymakers and the public.

Here we have focused on the role of theory shaping policy. In practice, of course, causality runs in both directions. Theorists often work on problems motivated by specific policy questions and specific experiences. Policymakers’ mind-sets and attitudes are influenced, perhaps subconsciously, by apparently remote developments in theory. Nevertheless, the most straightforward reading of developments in macroeconomic policy is that they were strongly influenced by developments in macroeconomic theory. To make our case, this Annual Report essay includes an analysis of optimal rules and monetary policy, which is appropriate consideration for the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, as well as a section describing how theory is pushing macroeconomics to new considerations. Our complete paper—from which this essay is based—also includes an analysis of fiscal policy. Interested readers can find the full paper in the Fall 2006 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives. (See note for full citation.)

Modern Theoretical Developments

Expectations and Macroeconomic Policy Analysis

The Lucas critique led economists to understand that people’s decision rules change when the way policy is conducted changes. Lucas (1976) forcefully argues that the question “How should policy be set today?” was ill-posed. In most situations, people’s current decisions depend on their expectations of what future policies will be. Those expectations depend, in part, on how people expect policymakers to behave. Macroeconomists now agree, therefore, that any sensible policy analysis must include a clear specification of how a current choice of policy will shape expectations of future policies.

To see more concretely why analyzing policy requires specifying how policy will be set in the future, consider two examples. First, consider a monetary authority deciding on monetary policy for today. This authority needs to forecast how variables such as inflation and output will behave now and in the future, which means that it must forecast private behavior in the future. But the decisions of private actors depend on their expectations about future monetary policy. If private actors expect tight monetary policy in the future, they will react to current price and wage pressures in one way; if they expect loose monetary policy in the future, they will react differently. Thus, the monetary authority cannot predict how the economy will respond to a policy decision today unless it can also predict how people’s expectations of future monetary policy will change as a result of the current decisions. The monetary authority also needs to predict how its own behavior will change in the future as a result of its current actions.

Next, consider a fiscal authority deciding how to tax capital income. This authority needs to forecast how output, investment, and other variables will respond to its decisions. Investment decisions, for example, depend on investors’ expectations of future tax rates. If investors expect future tax rates to be low, then they’ll invest more today; if high, then less today. Consequently, the fiscal authority cannot predict how investment will respond, for example, to a tax cut today unless it knows how people’s expectations of future tax rates will change as a result of the cut. The fiscal authority also needs to predict how its own future behavior will change as a result of its current actions.

With this concern over expectations in mind, macroeconomists now agree that a coherent framework for the design of economic policy consists of three parts: a model to predict how people will behave under alternative policies, a welfare criterion to rank the outcomes of alternative policies, and a description of how policies will be set in the future.

A commitment regime is the easiest environment to describe how future policies are set. In such a regime, all policies for today, tomorrow, the day after, and so on are set today and cannot be changed. These policies could be contingent on various events that might occur in the future. The model can then be used to predict the consequences of various plans for policy and can be used to find the optimal plan. This procedure has its origins in the public finance tradition stemming from Ramsey (1927), so this sequence of optimal policies is referred to as Ramsey policies and their associated outcomes as Ramsey outcomes.

Time Inconsistency Problem

The Lucas (1976) critique addresses situations in which expectations of future policies affect current decisions. The Lucas critique thus leads naturally to thinking about policy evaluation as comparing alternative sets of rules that describe policy both now and in the future. In practice, of course, societies may not be able to commit to future policies. In a series of graphic examples, Kydland and Prescott (1977) (soon followed by Calvo, 1978; Fischer, 1980) analyzes policies with and without commitment and shows that Ramsey policies are often time inconsistent; that is, outcomes with commitment are different from those without commitment. Their examples suggest that time inconsistency problems arise when people’s current decisions depend on expectations of future policies. Since people’s decisions have been made by the time the future date arrives, the government often has an incentive to renege on the Ramsey policies.

To better understand this problem, consider again examples from monetary and fiscal policy. The monetary policy example is motivated by the work of Kydland and Prescott (1977) and Barro and Gordon (1983). Assume that at the beginning of each period, wage setters choose nominal wages so as to attain a target level of real wages. The monetary authority then chooses the inflation rate. If inflation is higher than wage setters expected, then real wages are lower than the target level, firms demand more labor, and output is higher than its natural rate (which is its level when real wages are at their target level). The monetary authority wants to maximize society’s welfare, which is increasing in output and decreasing in inflation. As output increases, the natural assumption is that the marginal benefits of increases in output fall because of diminishing marginal utility. We assume in addition that as inflation increases, the marginal costs of increases in inflation rise. This assumption holds in many general equilibrium models.

To see that there is a time inconsistency problem in this setup, consider the best outcomes under commitment, the Ramsey outcomes. We think of commitment as a situation in which at the beginning of time society prescribes a rule for the conduct of monetary policy in all periods. The monetary authority then simply implements the rule. The best rule under commitment prescribes zero inflation in all periods. Under this rule, real wages are equal to their target level. To see why zero inflation is optimal, consider a rule that prescribes positive inflation. Wage setters anticipate positive inflation and set their nominal wages to be appropriately higher. Under this policy, real wages are still at their target level, output is unaffected, but inflation is positive. Clearly this outcome is worse than one under a policy that prescribes zero inflation.

Consider next outcomes with no commitment. We think of no commitment as a situation in which in each period the monetary authority chooses policy optimally given the nominal wages that wage setters have already chosen. In the resulting outcome, called the static discretionary outcome, inflation is necessarily positive while output is at its natural rate. To see why inflation is necessarily positive, suppose, by way of contradiction, that inflation rates are zero so that wage setters set their wages anticipating zero inflation. Once the nominal wages are set, however, the monetary authority will deviate and generate inflation in order to raise output. Hence, inflation must be positive. To see why output is at its natural rate, note that wage setters rationally anticipate the actions of the monetary authority so that real wages are at their target level. In the static discretionary outcome, inflation is at a high enough level so that the marginal cost of deviating to an even higher inflation rate is equal to the marginal benefit of increased output.

In the case of fiscal policy, a good example of the time inconsistency problem is based on Kydland and Prescott (1977). Consider a model in which the government needs to raise revenue from proportional taxes on capital and labor income to finance a given amount of government spending. Under commitment, society chooses a rule for setting tax rates in all periods, and the fiscal authority implements the rule. At any instant, the stock of capital is given by past investment decisions; however, the supply of labor can be changed relatively quickly. The key influence on investment decisions that determine the capital stock in the future is the after-tax return expected in the future, whereas the key influence on labor supply decisions is the current after-tax wage rate. So the government’s best policy for current tax rates is to tax capital at high rates and labor at low rates. This policy does not distort capital supply decisions, since the capital stock is fixed and irreversible in that capital goods cannot be directly converted into consumption goods. The policy also ensures that labor supply is not distorted much, since the tax rates on labor are low. For future tax rates, the best policy is to commit to set low rates on capital to stimulate investment and to raise the rest of the needed revenue with higher rates on labor.

Consider next the outcomes with no commitment. In each period, the fiscal authority still has an incentive to tax capital income heavily, since the capital stock is fixed, and to tax labor income lightly to avoid distorting labor supply. Without commitment, however, investors today rationally expect that high taxes on capital income will continue into the future—since such taxes are preferred in each time period—and investment will be low. In equilibrium, the capital stock is smaller than it would be under commitment, and both output and welfare are correspondingly lower than they would be under commitment.

The message of examples like these is that discretionary policymaking has only costs and no benefits, so that if government policymakers can be made to commit to a policy rule, society should make them do so. Our examples have no shocks. In stochastic environments the optimal policy rule is contingent on the shocks that affect the economy. A standard argument against commitment and for discretion is that specifying all the possible contingencies in a rule made under commitment is extremely difficult, and discretion helps policymakers respond to unspecified and unforeseen emergencies. This argument is less convincing than it may seem. Every proponent of rule-based policy recognizes the necessity of escape clauses in the event of unforeseen emergencies or extremely unlikely events. These escape clauses will, of course, reintroduce a time inconsistency problem, but in a more limited form. Almost by definition, deviations from such rules will occur rarely; hence, the time inconsistency problem arising from the escape clauses will be small. Commitment to a rule with escape clauses is not unworkable.

What can be done to ameliorate the time inconsistency problem short of commitment? A superficially attractive approach is to pass legislation requiring the monetary or the fiscal authority to abide by rules. This approach is more problematic than it may seem. In most macroeconomic environments with time inconsistency problems, given an initially established rule, all members of society (or a large majority) would like to deviate from it. Legislatures will have a strong incentive to allow the monetary or fiscal authority to deviate from the established rule. To be effective, therefore, attempts to ameliorate the time inconsistency problem must impose costs on policymakers of deviating from the earlier agreed-upon rules.

The most widely studied ways to impose such costs rely on either reputation or trigger strategy mechanisms. Such mechanisms can lead to better outcomes under discretion than the static discretionary outcomes. Indeed, if policymakers discount the future sufficiently little, these mechanisms can lead policymakers to choose the Ramsey outcomes.

Our illustration of such mechanisms draws on Chari, Kehoe, and Prescott’s (1989) analysis of the Kydland and Prescott (1977) and Barro and Gordon (1983) monetary policy example. Consider the following trigger strategy mechanism in an infinite horizon version of this example. In this mechanism, as long as the monetary authority has chosen the Ramsey policies in the past, wage setters expect it to continue to do so; however, if the monetary authority has ever deviated from the Ramsey policies, wage setters expect it to choose the static discretionary policies forever in the future. With these beliefs of private agents, the monetary authority understands that if it unexpectedly inflates, it gets a current gain from the associated rise in output but a loss in all future periods equal to the difference in welfare between the static discretionary outcome and the Ramsey outcome. In this situation, if the monetary authority discounts the future sufficiently little, then it will not deviate. Although the use of trigger strategy mechanisms is appealing, one difficulty is that many outcomes can result from trigger strategies, and how society will coordinate on a good outcome is not obvious.

Another device for ameliorating the time inconsistency problem is to delegate policy to an independent authority (Rogoff, 1985). One notion of what it means for an authority to be independent is that society faces large costs to dismiss the authority and replace it with another. We illustrate this device in the Kydland and Prescott (1977) monetary policy example, modified to include potential policymakers who differ in terms of their aversion to inflation. Suppose the appointed policymaker is extremely averse to inflation. After wage setters have chosen their nominal wages, this policymaker finds engineering a surprise inflation very costly. Wage setters anticipate this behavior, and the outcome is low inflation and output at its natural rate.

Note that if dismissing the authority is not costly, the delegation device is not effective. The authority will be dismissed after wage setters have set their nominal wages, and an authority more representative of society will be appointed. Wage setters will anticipate this behavior, and the outcomes will simply be the static discretionary outcomes. Making it costly to dismiss the authority essentially makes it costly for society to deviate from some set of rules and, hence, introduces a specific form of commitment.

Yet another device for ameliorating the time inconsistency problem is to set up institutions that ensure that policies cannot be implemented until several periods after they are chosen. To see the advantage of such implementation lags, recall the fiscal policy example. There, without commitment, the optimal policy is to set the tax rate of capital income high, since the capital stock is determined entirely by past investment decisions, and to set the tax rate on labor income low, since labor supply decisions are determined primarily by current tax rates. Suppose that the fiscal authority still chooses tax rates on capital and labor income, but that now these tax rates can only be implemented several periods after they are chosen. Under such institutions, choosing a high tax rate on capital income will tend to reduce investment, at least until the implementation date, and will lead to a corresponding reduction in the capital stock. In this environment, the delay in implementation means that policymakers are forced to confront at least part of the distortions arising from high capital taxation.

Optimal Rules and Monetary Policy

Macroeconomists can now tell policymakers that to achieve optimal results, they should design institutions that minimize the time inconsistency problem by promoting a commitment to policy rules. However, to what particular policies should policymakers commit themselves? For many macroeconomists considering this question, quantitative general equilibrium models have become the workhorse model, and they turn out to offer surprisingly sharp answers. Macroeconomists now generally agree on four properties that optimal policies should have and on when qualifications of those properties are appropriate. One of the four properties applies to monetary policy; the other three, primarily to fiscal policy.

Optimal Rules for Monetary Policy

In the area of monetary policy, the optimal rule is to set policy so that nominal interest rates and inflation will be low. This result is due to the celebrated work of Friedman (1969), which has been defended and supplemented by more recent work based on standard public finance principles.

Friedman’s argument stems from an analysis of the forces determining money-holding decisions. Money has benefits to individuals and therefore to society by reducing the costs of making transactions. From each individual’s perspective, the opportunity cost of money is the forgone nominal interest that could be obtained by investing it instead. From society’s perspective, the opportunity cost of producing money is close to zero. Thus, society should conduct monetary policy so that the nominal interest rate equals the opportunity cost of producing money and is therefore close to zero. This recommendation for monetary policy is known as the Friedman rule. (This rule should not be confused with a k-percent rule for monetary aggregates also advocated by Friedman.) This recommendation holds in both deterministic and stochastic environments.

An alternative way to implement the Friedman rule is to pay interest on money. Although it may be technologically difficult to pay interest on currency, it is possible to pay interest on checking accounts and other means of making transactions. This reasoning suggests that eliminating policies that limit interest payments on demand deposits, such as Regulation Q, move us closer to the Friedman rule.

Phelps (1973) makes what looks at first like a compelling argument that a nominal interest rate close to zero is unlikely to be optimal in practice. He notes that if government revenue must be raised through distorting taxes, the optimal policy is actually to tax all goods, including the liquidity services derived from holding money, so that the optimal interest rate is substantially greater than zero. Chari, Christiano, and Kehoe (1996) show, however, that for a class of economies consistent with the growth facts on the absence of long-term trends in the ratio of output to real balances, a nominal interest rate close to zero is in fact optimal, even if government revenue must be raised through distorting taxes. For such economies, money acts like an intermediate good, and for well-known public finance reasons, taxing intermediate goods is not optimal.

An intuitive way to think about the Friedman rule’s prescription that the nominal interest rate be zero is that it prescribes that the risk-adjusted real rate of return on money should be the same as the (risk-adjusted) real rate of return on other assets. In a deterministic environment, no risk adjustments are needed, so that the Friedman rule implies deflation at the real interest rate. Some economists have interpreted the Friedman rule as always requiring deflation at the real interest rate. Chari, Christiano, and Kehoe (1996), however, show that this interpretation is mistaken by showing that in a plausible parameterized stochastic environment, even though the optimal nominal interest rate is still zero, there is no deflation. Indeed, under the optimal policy the inflation rate is roughly zero because money turns out to be a hedge against real fluctuations, paying out relatively more in bad times and relatively less in good times. Indeed, money turns out to be enough of a hedge so that even at zero inflation, its risk-adjusted real rate of return equals that on other assets.

We turn now to some qualifications. In some well-known macroeconomic models, positive nominal interest rates are optimal. Typically, in these models, if the government had a rich enough set of fiscal instruments, then a zero nominal interest rate would be optimal, but positive nominal interest rates can make sense if the set of instruments available to the government is restricted.

Positive nominal interest rates are optimal in sticky price models with nominal prices or wages set in a staggered fashion and in which the government is restricted to uncontingent nominal debt and uncontingent consumption taxes. Absent such stickiness, even when the government is so restricted, zero nominal interest rates are optimal and volatile inflation is used to make nominal debt mimic real state-contingent debt (Chari, Christiano, and Kehoe, 1991). If nominal prices or wages are set in a staggered fashion, then such inflation volatility is costly because fluctuations in inflation induce undesirable fluctuations in relative prices. In this setting, optimal monetary policy trades off two desirable goals. One is to maintain price stability to avoid the misallocations induced by fluctuations in relative prices. The other goal is to minimize the social waste of using inefficient methods of conducting transactions. Not surprisingly, in this setting, optimal monetary policy involves a compromise between positive interest rates to reduce inflation and promote price stability and a nominal interest rate of zero (Benigno and Woodford, 2003; Khan, King and Wolman, 2003; Siu, 2004; Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe, 2004). The undesirable fluctuations in relative prices can be avoided if either state-contingent debt or state-contingent consumption taxes are available (Correia, Nicolini, and Teles, 2004).

Another set of environments in which positive nominal interest rates are optimal has a restricted set of assets available to share risk among individuals. In this setting, lump-sum transfers financed by printing money redistribute income from the temporarily rich to the temporarily poor. The reason is that inflation imposes a larger tax on those who hold more money and, in this setting, households who hold more money are the temporarily rich. Such transfers provide a form of risk sharing and therefore help raise welfare. Optimal monetary policy trades off the benefits of risk sharing against the social waste of using inefficient methods of conducting transactions, and that involves a positive nominal interest rate (Levine, 1991). Here, also, a rich enough set of fiscal policy instruments can provide a partial remedy, risk sharing, and allow the monetary authority to follow the Friedman rule (da Costa and Werning, 2003).

Thus, modern macroeconomic theory argues that positive nominal interest rates are optimal only if the set of instruments available to the government is restricted. Since this situation is highly likely in practice, optimal monetary policy involves a compromise between the goals of zero nominal interest rates and other goals. The robust finding is not that nominal interest rates should be literally zero but that nominal interest rates and inflation rates should be low.

The practical definition of low interest rates and inflation rates is a subject of continuing discussion, particularly because of biases in measuring inflation rates due to quality changes. Although no consensus has emerged on the definition of low inflation, most macroeconomists agree that a sustained inflation in excess of 3 percent per year is unacceptably high.

The Evolution of Monetary Policy

Over the last three decades, a variety of specific monetary policy proposals consistent with macroeconomic theory’s developments have been debated and implemented around the world. Central bankers and other monetary policymakers have begun to concentrate on price stability and inflation control as their main objectives. Many countries have changed their institutional frameworks for monetary policymaking in an apparent recognition of the time inconsistency problem. These changes have emphasized the importance of characteristics key to minimizing that problem—credibility, transparency, and accountability—as well as clear statements, or rules, about the objectives of monetary policy and the methods by which that policy will respond to varying circumstances. All these changes point to a shift in the world toward the rule-based method of policymaking, which is prescribed by modern macroeconomic theory.

Two kinds of institutional changes are especially evident in the practice of monetary policy. Central banks have become substantially more independent of the political authorities, and to an increasing extent, the charters of central banks have emphasized the primacy of inflation targeting and price stability.

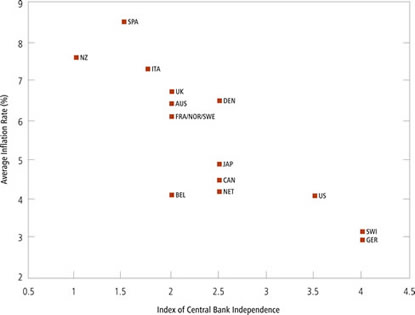

An extensive empirical literature has argued that central bank independence helps reduce inflation rates without any adverse consequences on output. Figure 1, which reproduces Figure 1A from Alesina and Summers (1993), shows that countries with more independent central banks tend to have lower inflation rates. Alesina and Summers (1993) also show that countries with more independent central banks do not suffer in terms of output performance. One interpretation of these findings is that institutions that promote central bank independence ameliorate the time inconsistency problem. Under this interpretation, the findings in the literature support the key feature of the Kydland and Prescott (1977) example: Reducing the time inconsistency problem ameliorates inflation but has no effect on output.

Figure 1: Central Bank Independence vs. Inflation

Measures of Central Bank Independence vs. Average Rates of Inflation in 16 Countries, 1973-88

Source: Alesina and Summers (1993)

Bernanke et al. (1999) argue that inflation targeting is moving toward a rule-based regime. Their idea (p. 24) is that “inflation targeting requires an accounting to the public of the projected long run implications of its short run policy actions.” This accounting can help ameliorate the time inconsistency problem by ensuring that the long-run implications of short-run policy actions are explicitly taken into account in the policymaking process.

In practice, inflation targeting often involves setting bands of acceptable inflation rates. (See, for example, Bernanke and Mishkin, 1997.) In theoretical models without private information, optimal policy does not involve setting bands, but rather involves specifying exactly what the monetary authority should do in every state. In this sense, such models imply that the monetary authority should have no discretion. Athey, Atkeson, and Kehoe (2005) construct a model in which the monetary authority has private information about the economy and show that the optimal policy allows for limited discretion in that it specifies acceptable ranges for inflation and gives the monetary authority complete discretion within those ranges. In this way, Athey, Atkeson, and Kehoe provide a theoretical rationale for the type of inflation targeting often seen in practice.

Perhaps the most vivid example of both the movement toward independence and the movement toward a rule-based method of policymaking is to be found in the charter of the European Central Bank (ECB). Article 105 of the treaty establishing the central bank states that “the primary objective” of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) shall be to “maintain price stability.” Article 107 of the treaty emphasizes and protects the independence of the central bank by mandating that “neither the ECB, nor a national central bank, nor any member of their decision-making bodies shall seek or take instructions from Community institutions or bodies, from any government of a Member State or from any other body.” Furthermore, the Maastricht Treaty and the Stability and Growth Pact contain provisions restricting fiscal policies in the member countries in order to make the pursuit of price stability easier.2 The change in the conduct of European monetary policy is especially marked for countries other than Germany in the European monetary union.

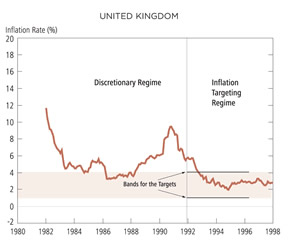

Over the last 20 years, monetary policy in the United Kingdom has also moved in the direction of greater independence as well as toward rule-based policymaking. After experiencing a major exchange rate crisis, the United Kingdom adopted a form of inflation targeting in October 1992. In May 1997 (and subsequently formalized by the Bank of England Act of 1998), the Bank of England gained operational independence from the government. The Bank of England is now specifically required primarily to pursue price stability and only secondarily to make sure that its policies are consistent with the growth and employment objectives of the government. The government periodically sets an inflation target, currently 2 percent, and the central bank is given broad freedom in achieving this target. As part of the inflation target, the government also sets ranges for acceptable fluctuations in inflation. If inflation moves outside its target range, the central bank is required to report on the causes for this deviation, the corrective policy action the central bank plans to take, and the time period within which inflation is expected to return to its target range.

The movement toward rule-based monetary policy is widespread. By 2002, 22 countries had adopted monetary frameworks that emphasize inflation targeting (Truman, 2003). The following countries are listed by the date in which inflation targeting was adopted (and in some cases readopted): in 1989, New Zealand; in 1990, Chile; in 1991, Canada and Israel; in 1992, the United Kingdom; in 1993, Australia, Finland, and Sweden; in 1995, Spain and Mexico; in 1997, Czech Republic and Israel (again); in 1998, Poland and Korea; in 1999, Brazil, Chile (again), and Colombia; in 2000, Thailand and South Africa; in 2001, Hungary, Iceland, and Norway; in 2002, Peru and the Philippines. These countries have all openly published their inflation targets and have described their monetary framework as one of targeting inflation. Clearly, inflation targeting is worldwide; the countries range from developed economies to emerging market economies. The number of countries adopting inflation targeting is growing over time.

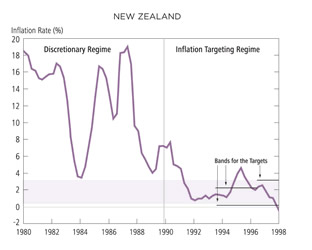

The first country to adopt inflation targeting, New Zealand, has gone the furthest in setting up a rule-based regime. Before 1989, monetary policy in New Zealand was far from being rule-based. As Nicholl and Archer (1992, p. 316) describe:

New Zealand experienced double digit inflation for most of the period since the first oil shock. Cumulative inflation (on a Consumer Price Index (CPI) basis) between 1974 and 1988 (inclusive) was 480 percent. ... Throughout the period, monetary policy faced multiple and varying objectives which were seldom clearly specified, and only rarely consistent with achievement of inflation reduction.

In 1989, the government of New Zealand adopted legislation mandating that the objective of the central bank be to maintain a stable general level of prices. The government and the governor of the central bank must agree to a policy target, which specifies an acceptable range for inflation. Since the act was adopted, the inflation rate has fallen considerably and has been well below 5 percent per year over the last decade or so.

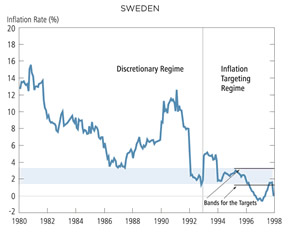

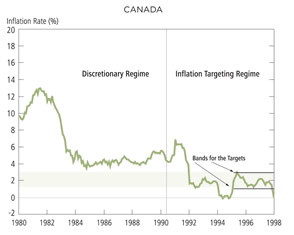

Figure 2 displays the inflation experiences for four countries—the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Canada, and Sweden—that have adopted inflation targeting. The four panels of Figure 2 show the inflation rates before and after the date of the inflation targeting regime, marked by a vertical line. The bands in the figure following the adoption of the inflation targeting regime depict ranges of inflation as specified in the regime. Although the countries did not always remain within the target range for inflation after adopting inflation targeting, inflation fell substantially in all the countries after the adoption of inflation targeting. The literature contains ongoing controversy about whether this decline was solely due to inflation targeting, but also offers substantial consensus that inflation targeting played an important role in the decline.

Figure 2: Examples of Inflation in Discretionary and Targeting Regimes, 1980-98

Even in countries that have not explicitly adopted inflation targeting, the institutional framework for the conduct of monetary policy has changed in a way consistent with modern macroeconomic theory. In the United States, for example, the central bank has been moving toward openness and targeting for the last 25 years. The Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of 1978 (commonly referred to as the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act) required the Federal Reserve Board of Governors to report periodically to Congress on the planned course of monetary policy. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve Board has changed some policies in ways that increase transparency. For example, the minutes of Federal Open Market Committee meetings are now released substantially sooner than they used to be, and the FOMC’s decisions regarding its interest rate target are now released immediately after the meeting. A large academic literature motivated by Taylor (1993) argues that the Fed has effectively moved toward a rule-based regime and is therefore well placed to solve the time inconsistency problem.

Although the changes in the practice of monetary policy documented above cannot be definitively linked to the recent theoretical developments in macroeconomics, the most straightforward explanation for these changes is that they are due to the identification of the time inconsistency problem by macroeconomic theorists.

Extending the Bounds of Macroeconomics

Macroeconomic theorists have long focused on frictions in the labor market as a source and propagation mechanism for business cycles. Over the last few years, a significant focus of macroeconomic research has been the effects of government policies on the secular trends of labor markets. The distinguishing feature of this research is that it is based on quantitative general equilibrium models along the lines inspired by Kydland and Prescott (1982). Although the work in this area has not yet progressed to definitive policy prescriptions, it is beginning to offer powerful insights into what may have caused some problems in labor markets and what sorts of policy changes might be part of the solutions.

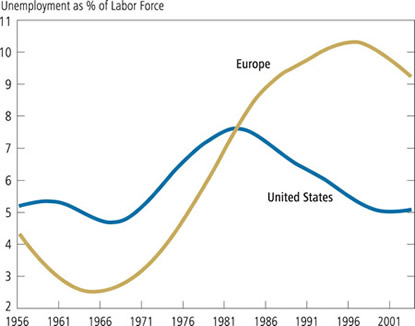

An issue that has captured much scientific and popular attention has been the recent stubbornly high rates of unemployment in Europe. Figure 3 shows the behavior of average unemployment rates in Europe and the United States from 1956 to 2003. Until the late 1970s, unemployment was roughly two percentage points lower in Europe than in the United States. Since about 1980, European unemployment increased significantly while U.S. unemployment decreased. By 2003, unemployment averaged more than 9 percent in Europe, compared with only about 5 percent in the United States.

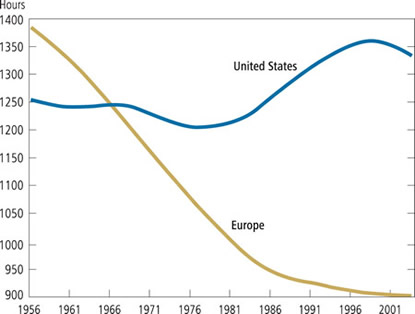

Another way to examine labor markets is to focus on employment rates, measured as the annual average hours worked per adult of working age. Figure 4 displays the behavior of this measure of employment rates in Europe and the United States from 1956 to 2003. According to this figure, employment steadily declined over the entire period in Europe, whereas in the United States, it was roughly stable until the 1980s and then sharply increased.

Figures 3 & 4: Unemployment and Employment in Europe and the United States, 1956-2003

Average Annual Hours Worked

What explains these contrasting patterns? The macroeconomics literature has advanced three explanations for these patterns: labor market rigidities, taxes, and unemployment benefits.

Labor Market Rigidities

One widely held view is that labor markets are much more rigid in Europe than in the United States. For example, European legal employment protections that make it difficult to fire workers are typically more stringent than those in the United States. Hopenhayn and Rogerson’s (1993) general equilibrium model points to two opposing forces of firing costs on unemployment: The costs make firms more reluctant to fire workers, thereby reducing unemployment, but at the same time, they make firms more reluctant to hire workers in the first place, thereby raising unemployment. The overall effect is ambiguous and depends on the details of the microeconomic shocks affecting individual firms’ employment decisions. Using cross-country evidence, Nickell (1997) finds that the effect of hiring costs is also ambiguous.

Although the effect of firing costs on unemployment is ambiguous, the effect on productivity in the Hopenhayn and Rogerson (1993) model is not. Firing costs tend to inhibit the efficient reallocation of labor to more productive firms and thereby reduce aggregate productivity. Thus, this model implies that welfare can be raised by reducing firing costs. Note that if workers cannot borrow against future earnings to invest in general human capital, then firing costs may provide incentives for firms to invest in such capital and thus raise productivity, as in the models of Acemoglu and Pischke (1999) and Chari, Restuccia, and Urrutia (2005).

Taxes

Prescott (2002) and Rogerson (2005) point to differences in taxes as a key source of the differences in European and U.S. labor market experiences. To study this possibility, the discipline of general equilibrium theory is essential, because the effect of taxes on labor market outcomes depends not only on how tax revenue is raised but also, as Rogerson (2005) emphasizes, on how it is used. A tax has both a substitution effect that reduces the incentive to work and an income effect that increases the incentive to work, but the way in which tax revenue is spent can alter the income effects.

To see why the details of how tax revenues are spent are important, suppose first that the revenue is used to provide public goods that are poor substitutes for private consumption. Then, as long as the utility function has near unit elasticity of substitution between consumption and leisure, the income and substitution effects nearly cancel so that labor supply effects of taxes are approximately zero. Hence, to a first approximation, the public good expenditures crowd out private consumption dollar for dollar. Suppose next that the revenue is either transferred back to private citizens in a lump-sum fashion or, equivalently, used to purchase private goods for citizens. Then taxes have only a substitution effect—because the expenditures offset the income effect—and labor supply falls.

Prescott (2002) cleverly sidesteps these issues by noting that in a general equilibrium model, the details of the expenditures are captured by their effects on consumption. Prescott begins his analysis by noting that in a general equilibrium model with a stand-in household, the first-order condition determining labor supply equates the marginal rate of substitution between consumption and leisure to the after-tax marginal product of labor. Given consumption and the capital stock, this condition thus implies a relation between employment and the tax-induced labor wedge. In this approach, the details of how government revenues are spent play a role in determining labor supply only through its effects on consumption and the capital stock.

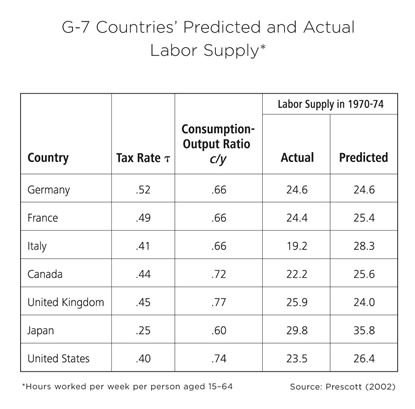

Assuming that both the utility function and the production function have

unit elasticity of substitution, and using long-term averages to pin

down share parameters, Prescott showed that this simple theory works

surprisingly well in accounting for employment observations for the G-7

countries for the 1970s and the 1990s. With these functional form

assumptions, the marginal rate of substitution is proportional to c/(1–l), where c denotes consumption and l the fraction of time in

market work, whereas the after-tax marginal product of labor is

proportional to (1–![]() )y/l, so that the consumption-to-output ratio, c/y, summarizes the effects of the details of expenditures as well as

other aspects of the model, such as capital income taxes. The

accompanying table is reproduced from Prescott (2002). The closeness

between the predictions of his simple model and the data is remarkable.

)y/l, so that the consumption-to-output ratio, c/y, summarizes the effects of the details of expenditures as well as

other aspects of the model, such as capital income taxes. The

accompanying table is reproduced from Prescott (2002). The closeness

between the predictions of his simple model and the data is remarkable.

The Prescott analysis works well in a comparison of the early 1970s and the mid-1990s, in part because tax policies clearly changed dramatically during this time. Using his analysis to compare the 1950s and the 1970s, however, does not work as well. Evidence of large changes in tax rates from the 1950s to the 1970s is hard to find, even though Figure 4 shows a sustained decline in employment rates over this period. As Prescott has acknowledged, his analysis likewise does not work well for the Scandinavian countries that have both high tax rates and high employment.

Rogerson (2005) builds on Prescott’s analysis to allow for secular shifts from agriculture and industry toward services. Rogerson argues that changes in taxes and in industry composition can account for the bulk of observed differences in employment between Europe and the United States.

These analyses focus on the division of time between market work and all forms of nonmarket activities—including both unemployment and being out of the labor force. As such, these analyses have sharp implications for the behavior of the employment rate. Since they do not distinguish between search activities and other nonmarket activities that lead households to be classified as out of the labor force, they are silent about differences in unemployment rates between Europe and the United States.

Unemployment Benefits

One possible reason the unemployment rate is higher in Europe than in the United States is that unemployment benefits are more generous in Europe. A reasonable conjecture is that this greater generosity leads to higher unemployment rates by making workers more reluctant to accept job offers. The problem with this conjecture is that it seems contradicted by facts; in the 1960s and 1970s, unemployment benefits were much more generous in Europe than in the United States, while unemployment rates were lower in Europe than in the United States. Ljungqvist and Sargent (1998) develop a model that focuses on the division of time between market work and the search activities of unemployed workers while abstracting from considerations of nonmarket activities other than search. They show that in the 1960s and 1970s, more generous unemployment benefits, together with higher firing costs, led Europe to have lower unemployment rates than the United States, whereas in the 1980s, the same benefits and firing costs led to the opposite relationship.

The key difference between the earlier and later periods is that microeconomic turbulence, measured as fluctuations in individual worker productivities, has increased over time in both Europe and the United States (Gottschalk and Moffitt, 1994). As microeconomic turbulence increases, more workers find themselves in low-productivity jobs as well as in unemployment. If unemployment benefits are generous, as they are in Europe, then unemployed workers’ reservation wages fall by only a small amount as turbulence increases, and the flow of workers out of unemployment does not change much. Hence, with increased microeconomic turbulence, the overall unemployment rate rises. If unemployment benefits are meager, as they are in the United States, then workers’ reservation wages fall sharply as turbulence increases, and the outflow from unemployment rises nearly one-for-one with the inflow. Hence, the unemployment rate does not change much.

The Ljungqvist and Sargent (1998) model assumes that workers are risk-neutral, in which case unemployment compensation has no benefits and is costly because it distorts the search decision. As the model stands, the policy implication is that government-provided unemployment benefits should be eliminated. With risk aversion and imperfections in private markets for unemployment insurance, unemployment insurance has benefits that need to be weighed against the induced distortions in search decisions. A growing literature has begun to analyze these trade-offs (for example, Atkeson and Lucas, 1992; Hopenhayn and Nicolini, 1997; Shimer and Werning, 2005).

In our view, explanations of patterns in European and U.S. labor markets based on labor market rigidities, taxes, and unemployment benefits all have plausible appeal, but the quantitative importance of each has not been definitively established.

Conclusion

Here we have argued that macroeconomic theory has had a profound and far-reaching effect on the institutions and practices governing monetary policy and is beginning to have a similar effect on fiscal policy. The marginal social product of macroeconomic science is surely large and growing rapidly.

Those economists caught up in the frenzy of day-to-day policymaking often view their colleagues who toil in the ivory towers of academe as having no power to affect practical policy and those economists who whisper in the ears of presidents and members of Congress as having the ability to dramatically affect policy. The truth, as we have argued, is very far from this view. The course of practical policy is affected primarily by the institutions we devise and how well presidents and members of Congress understand economic trade-offs. The day-to-day economic adviser is useful to the extent that the adviser can educate policymakers about trade-offs, but is largely irrelevant otherwise. It is easy to see why those economists caught up in the whirlwind of day-to-day policymaking miss the dramatic changes in policy that result from slow, secular changes in institutions, practices, and mind-sets.

The toilers in academe are uniquely placed to develop analyses of institutions and to educate the public and policymakers about economic trade-offs. The essence of our argument is that, at least in macroeconomics, these toilers have delivered large returns to society over the last several decades.

Notes

1 The use of dynamic general equilibrium models in macroeconomics has a long tradition dating back, at least, to Robert Solow (1956).

2 Note that these practical concerns are consistent with the work of Sargent and Wallace (1985), who emphasize that monetary and fiscal policy are linked by a single government budget constraint, so that responsible monetary policy is impossible without responsible fiscal policy.

References

Acemoglu, Daron and Jörn-Steffen Pischke. 1999. “The Structure of Wages and Investment in General Training.” Journal of Political Economy. June, 107:3, pp. 539–72.

Alesina, Alberto and Lawrence H. Summers. 1993. “Central Bank Independence and Macroeconomic Performance: Some Comparative Evidence.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking. May, 25:2, pp. 151–62.

Athey, Susan, Andrew Atkeson and Patrick J. Kehoe. 2005. “The Optimal Degree of Discretion in Monetary Policy.” Econometrica. September, 73:5, pp. 1431–75.

Atkeson, Andrew and Robert E. Lucas Jr. 1992. “On Efficient Distribution with Private Information.” Review of Economic Studies. July, 59:200, pp. 427–53.

Barro, Robert J. and David Gordon. 1983. “Rules, Discretion and Reputation in a Model of Monetary Policy.” Journal of Monetary Economics. July, 12:1, pp. 101–21.

Benigno, Pierpaolo and Michael Woodford. 2003. “Optimal Monetary and Fiscal Policy: A Linear-Quadratic Approach.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 9905, August.

Bernanke, Ben S., Thomas Laubach, Frederic S. Mishkin and Adam S. Posen. 1999. Inflation Targeting: Lessons from the International Experience. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Bernanke, Ben S. and Frederic S. Mishkin. 1997. “Inflation Targeting: A New Framework for Monetary Policy?” Journal of Economic Perspectives. Spring, 11:2, pp. 97–116.

Calvo, Guillermo A. 1978. “On the Time Consistency of Optimal Policy in a Monetary Economy.” Econometrica. November, 46:6, pp. 1411–28.

Chari, V. V., Lawrence J. Christiano and Patrick J. Kehoe. 1991. “Optimal Fiscal and Monetary Policy: Some Recent Results.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking. August, 23:3, pp. 519–39.

Chari, V. V., Lawrence J. Christiano and Patrick J. Kehoe. 1996. “Optimality of the Friedman Rule in Economies with Distorting Taxes.” Journal of Monetary Economics. April, 37:2, pp. 203–23.

Chari, V. V., Patrick J. Kehoe and Edward C. Prescott. 1989. “Time Consistency and Policy.” In Modern Business Cycle Theory, edited by Robert Barro. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, pp. 265–305.

Chari, V. V., Diego Restuccia and Carlos Urrutia. 2005. “On-the-Job Training, Limited Commitment, and Firing Costs.” Working Paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Cooley, Thomas, F., ed. 1995. Frontiers of Business Cycle Research. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Correia, Isabel, Juan Pablo Nicolini and Pedro Teles. 2004. “Optimal Fiscal and Monetary Policy: Equivalence Results.” Working Paper, Bank of Portugal.

da Costa, Carlos and Iván Werning. 2003. “On the Optimality of the Friedman Rule with Heterogeneous Agents and Non-Linear Income Taxation.” Mimeo, University of Chicago.

Fischer, Stanley. 1980. “Dynamic Inconsistency, Cooperation, and the Benevolent, Dissembling Government.” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. February, 2:1, pp. 93–107.

Friedman, Milton. 1969. “The Optimum Quantity of Money.” In The Optimum Quantity of Money and Other Essays. Chicago: Aldine, pp. 1–50.

Gottschalk, Peter and Robert Moffitt. 1994. “The Growth of Earnings Instability in the U.S. Labor Market.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Issue 2, pp. 217–72.

Hopenhayn, Hugo A. and Juan Pablo Nicolini. 1997. “Optimal Unemployment Insurance.” Journal of Political Economy. April, 105:2, pp. 412–38.

Hopenhayn, Hugo and Richard Rogerson. 1993. “Job Turnover and Policy Evaluation: A General Equilibrium Analysis.” Journal of Political Economy. October, 101:5, pp. 915–38.

Khan, Aubhik, Robert G. King and Alexander L. Wolman. 2003. “Optimal Monetary Policy.” Review of Economic Studies. October, 70:247, pp. 825–60.

Kydland, Finn E. and Edward C. Prescott. 1977. “Rules Rather than Discretion: The Inconsistency of Optimal Plans.” Journal of Political Economy. June, 85:3, pp. 473–91.

Kydland, Finn E. and Edward C. Prescott. 1982. “Time to Build and Aggregate Fluctuations.” Econometrica. November, 50:6, pp. 1345–70.

Levine, David K. 1991. “Asset Trading Mechanisms and Expansionary Policy.” Journal of Economic Theory. June, 54:1, pp. 148–64.

Ljungqvist, Lars and Thomas J. Sargent. 1998. “The European Unemployment Dilemma.” Journal of Political Economy. June, 106:3, pp. 514–50.

Lucas, Robert E., Jr. 1976. “Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique.” Journal of Monetary Economics. Supplementary Series, 1:2, pp. 19–46.

Nicholl, Peter W. E. and David J. Archer. 1992. “An Announced Downward Path for Inflation.” Reserve Bank Bulletin. 55:4, pp. 315–23. New Zealand Reserve Bank.

Nickell, Stephen. 1997. “Unemployment and Labor Market Rigidities: Europe versus North America.” Journal of Economic Perspectives. Summer, 11:3, pp. 55–74.

Phelps, Edmund. 1973. “Inflation in the Theory of Public Finance.” Swedish Journal of Economics. March, 75, pp. 67–82.

Prescott, Edward C. 2002. “Richard T. Ely Lecture: Prosperity and Depression.” American Economic Review. May, 92:2, pp. 1–15.

Ramsey, Frank P. 1927. “A Contribution to the Theory of Taxation.” Economic Journal. March, 37:145, pp. 47–61.

Rogerson, Richard. 2005. “Structural Transformation and the Deterioration of European Labor Market Outcomes.” Mimeo, Arizona State University.

Rogoff, Kenneth. 1985. “The Optimal Degree of Commitment to an Intermediate Monetary Target.” Quarterly Journal of Economics. November, 100:4, pp. 1169–89.

Sargent, Thomas J. and Neil Wallace. 1985. “Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review. Winter, 9:1, pp. 15–31.

Schmitt-Grohé, Stephanie and Martín Uribe. 2004. “Optimal Fiscal and Monetary Policy under Sticky Prices.” Journal of Economic Theory. February, 114:2, pp. 198–230.

Shimer, Robert and Iván Werning. 2005. “Liquidity and Insurance for the Unemployed.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 11689.

Siu, Henry E. 2004. “Optimal Fiscal and Monetary Policy with Sticky Prices.” Journal of Monetary Economics. April, 51:3, pp. 575–607.

Solow, Robert, M. 1956. “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth.” Quarterly Journal of Economics. 70:1, pp. 65–94.

Taylor, John B. 1993. “Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy. December, 39, pp. 195–214.

Truman, Edwin M. 2003. Inflation Targeting in the World Economy. Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics.