Imagine yourself in a wheelchair and needing medical attention, but you're unable to make it through a doorway.

Now imagine that you're already in the hospital. Hope you don't have to use the restroom, because the bathrooms are too small for both you and the nurse who assists you.

That was the facility situation facing Mitch Leupp, CEO of the Mountrail County Medical Center, and the community of Stanley, N.D. The facility opened as the Stanley Community Hospital in 1950, serving this small community of 1,300 people in the very rural northwestern corner of the state. A clinic was added in 1959, and additions were tacked onto the hospital three times, the last one in 1975.

In 1997, a nearby nursing home bought the hospital and clinic, and the new entity was reorganized as the Mountrail County Medical Center, sharing staff, administration and other features. But for decades, large capital improvements at the hospital were largely out of the question because the facility was serving a shrinking population base and "had been losing money for a number of years," Leupp said.

So when push came to shove in the spring of 1999, Leupp and the organization's board decided they had no choice but to improve the hospital and clinic. "You do (the improvements) or you shut down," Leupp said. "I think to a certain degree you had to do it. The buildings were absolutely antiquated."

If a small community loses such institutions, they aren't likely to come back. This was particularly the case for Stanley, given the area's aging, declining population. "For us, the new building was survival," Leupp said. "Without it, we wouldn't be here."

So Leupp went to meetings, 70 in all, from May to August of that year, and a surge of community support raised enough money, combined with a $1 million federal loan, to cut the ribbon four years later on a brand new $3.6 million facility. In fact, the fund raising was so successful that Mountrail today effectively has no debt service on the project, having already paid back the government loan.

Mountrail's experience might sound like the exception to the rule among rural hospitals, a good-guys-finally-win story. And, in fact, that appears to be the case in its own state. But Mountrail is part of a broader trend of accelerated capital investment in hospitals, clinics and other medical offices across much of the Ninth District and the nation, in virtually all urban areas, but also in many rural ones.

In St. Paul, Minn., alone, three major hospital projects have been recently announced or are currently under way at a total cost of more than $325 million (including Regions Hospital's most recent $179 million renovation and expansion), and that doesn't include numerous smaller improvement projects at hospitals, clinics and specialty care offices in that city.

A federal advisory agency reported in March of last year that spending on hospital construction "has increased substantially in recent years, and more than 85 percent of nonprofit hospitals plan to add capacity in the next two years."

One hospital official in Sioux Falls, S.D., noted "an incredible amount of activity" among providers in the region. In Montana, people have been wondering why there are "all those cranes at the hospitals" around the state, according to Jim Ahrens of the Montana Hospital Association. "There's a lot of stuff on drawing boards."

Capital improvements are even coming to many rural hospitals—the first sizable investment in decades for some—thanks in large part to a federal critical access program designed to help such hospitals shore up their bottom line.

Understanding capital investment trends among health care providers is important at a variety of levels. For the local community, such spending creates new services and immediate value as construction crews turn a hole in the ground into a life-saving institution. The bricks and mortar are but the start; these new facilities have long economic coattails. Truckloads of medical and office equipment fill up the new space, and the latest information technology helps the building do its job more efficiently. Most important, once construction crews leave, the real work starts: Health care workers get busy healing the sick and injured.

None of it comes cheap, however. And despite the physical appearance of growth, operating margins are getting squeezed virtually across the board. As a result, capital investment has focused on higher-margin kinds of services. Particularly in urban areas seeing the biggest spurt of new projects, worries are creeping up of a medical "arms race" in which health care organizations compete not on price or even quality of care, but on shiny new buildings, machines that go "ping" and well-appointed accommodations targeted to patients that help their bottom lines.

At the other end of the spectrum, most often in small rural hospitals, meager margins have collided with a growing wish list of investments in medical equipment and information technology. This means that, despite a relative spending splurge in many rural areas, facilities are still struggling to stay up to date with technology.

Excuse the dust

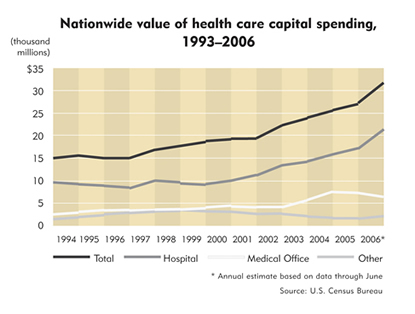

Data on health care capital spending are not particularly neat and tidy, but what are available show strong recent growth. Nationally, data from the U.S. Census Bureau's construction survey show steady upward growth in the 1990s, with a bit of a slowdown in the latter part of the decade.

But spending took a decided upturn about 2001, foreshadowed that year in a survey by the Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA), an industry group for health care finance executives. In that survey, hospital CFOs said that capital spending would increase by 14 percent per year from 2001 to 2006. Pretty close: According to Census figures, national spending growth ended up at about 13 percent per year (see chart).

Evidence at the state level, as well as anecdotes from industry officials, suggests that health care capital spending also started increasing about six years ago in the district, although the uptick came later for some states. Generally, capital spending has been robust this decade for all district states except North Dakota, though providers in metro regions there appear to be active.

Minnesota and Wisconsin both track health care capital spending, thanks to requirements that the state government review and approve projects to ensure compliance with various guidelines and regulations. These data are fairly volatile because the "recorded date" (generally for either state approval or spending commitment) might not coincide with actual construction activity, and a calendar shift of a few large projects can skew annual figures.

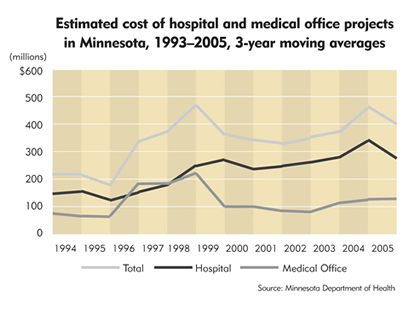

With those caveats, health care capital spending nonetheless appears to be strong in the district. That's particularly the case of late in Minnesota, according to a Department of Health database. A three-year smoothed annual average (which reduces volatility) shows investment peaks in 1998 and 2004, with something of a lag in the middle (see chart). The 1998 peak is mostly the result of a massive, $400 million expansion of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester—by far the single largest project in the state in the past two decades—which inflated the overall trend line. Though the smoothed average shows decline since 2004, spending commitments in the calendar year 2005 were particularly strong, and 2006 appears to be something of an investment breather. However, data for last year run only through August.

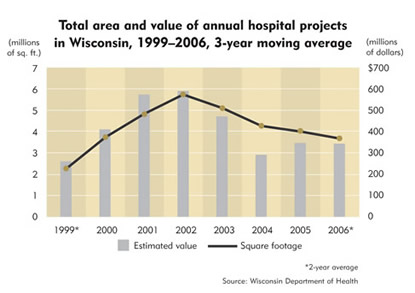

The trend is similar, although not identical, in Wisconsin: The overall value and square footage of projects peaked in 2001 and 2002, and has slowly ebbed while staying fairly strong (see chart). That trend line probably stems from large hospitals in the state's metro areas, which saw major expansions and renovations in the early part of this decade, according to George Quinn, senior vice president of finance for the Wisconsin Hospital Association (WHA).

Activity across the district has been universally strong in district metro areas, according to sources. In Fargo, N.D., "they have things going on everywhere over there," said Monte Engel, a manager with the state Health Facilities Division.

In Billings, Mont., the Deaconess Billings Clinic is in the middle of a multiyear, $100 million capital improvement plan for the campus. Deaconess broke ground in 2004 on a $27 million expansion of its emergency and trauma center, and currently has plans to build a multimillion-dollar cancer research and treatment center to compete with an existing cancer center in town owned by St. Vincent Healthcare.

In South Dakota, business at Fiegen Construction has been steady "for a good decade," said President Jeff Fiegen. The company is a design-build construction firm and a partner with Avera Health, a regional health care company with more than 100 medical facilities concentrated in eastern South Dakota and surrounding areas in Minnesota, Iowa and Nebraska. "I don't know that we've ever seen a slowdown," Fiegen said.

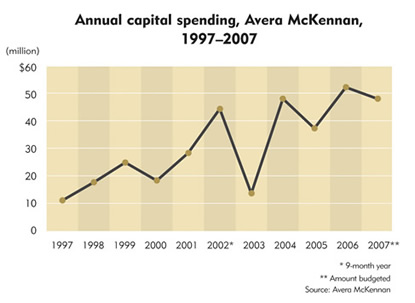

Avera McKennan Hospital and University Health Center in Sioux Falls is a member of Avera Health. Since 1997, the organization's annual capital budget has zigged and zagged a bit, but overall it has steadily increased (see chart). Last year Avera McKennan unveiled a new $32 million behavioral health facility and a $6 million outpatient imaging center, and this year it expects to complete a new $8 million emergency department. Its cross-town rival, Sioux Valley Health System, opened a $55 million surgical center last year, is in the middle phase of a new cancer center and is raising funds for a $40 million children's hospital it hopes to open next year.

The cement trucks aren't rolling just to hospitals. Fiegen said his office started seeing steady activity "about five or six years go" in clinic expansions in Tea, Harrisburg and other communities surrounding Sioux Falls, as well as new offices for specialty care areas like dermatology, ophthalmology and dentistry. That activity in medical offices can be seen elsewhere in the district as well. A report last year on the Twin Cities market by United Properties noted that new construction of medical offices there was "at an all-time high."

Nationwide, there has also been a surge in specialty care facilities, most of it landing in metro regions. For example, from 1996 to 2005, the number of freestanding ambulatory care surgery centers (in essence, outpatient surgery centers) has more than doubled to 5,100, according to the American Hospital Association. Another niche—physician-owned specialty hospitals—saw its numbers roughly double between 2002 and 2004, according to a report last summer by MedPAC, a federal agency established to advise Congress on Medicare issues. Activity was so fast and furious that Congress slapped an 18-month moratorium on physician-owned specialty hospitals that expired in June of 2005.

How this national expansion has played out in the district is unknown; figures could not be found for these specialty care facilities, though some evidence suggests that activity has been stronger elsewhere, particularly in southern regions seeing strong in-migration of retirees, who consume a disproportionate amount of health care.

A quieter boom

While their pace of activity might not match that of metro regions, rural health care providers appear to be seeing an uptick in capital spending just the same, according to industry sources and widely gathered anecdotes.

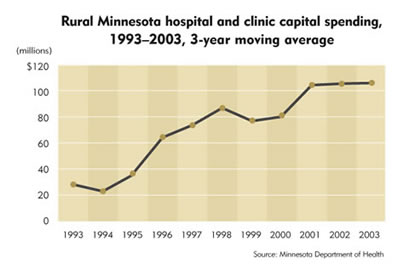

"I wouldn't call it a boom. But it's gotten busier in the last four or five years," said Gregg Redfield, vice president of finance for the Minnesota Hospital Association. According to data from the Minnesota Department of Health, capital spending among rural hospitals and clinics trended up steadily from 1993 to 2003 (see chart).

But quantifying the trend among rural health care facilities in the past few years, and elsewhere in the district, involves more guesswork and extrapolating from anecdotes. In some cases, rural investment is easy to track because it's simply not happening. Outside of North Dakota's metros—Bismarck, Fargo and Grand Forks—hospital investment "pretty much falls off the table," according to Engel, from the state Health Facilities Division.

Arnold "Chip" Thomas, president of the North Dakota Healthcare Association (NDHA), said rural hospitals are making the necessary fire and safety improvements to remain code compliant, but have not otherwise seen any increase in capital investment of late. Noting Mitch Leupp's success in getting a new hospital built in Stanley, Thomas said that "Mitch is not really reflective of the state."

Still, circumstantial evidence suggests that the medical building boom has spread to other rural areas in the district, and not just in regional population centers, but in truly small towns. Hospitals in mid-size South Dakota cities like Aberdeen, Mitchell and Yankton—each with between 10,000 and 25,000 people—have undertaken major improvements in recent years; likewise for hospitals in Stanley and Hayward, towns of about 2,000 each in northern Wisconsin. In Montana, hospitals in Malta (pop. 1,000) and White Sulpher Springs (pop. 2,100) got major upgrades.

There are even instances of communities getting completely new facilities—almost unheard of in years past. In South Dakota, Faulk County Memorial Hospital is getting a new facility—this in a county with just 2,600 people—"and two other (small) communities are talking about it," said Kenneth Senger of the South Dakota Association of Healthcare Associations (SDAHA).

In the past few years, new hospitals have been built in Aitkin, Luverne, St. Peter and Staples, all cities of less than 10,000 located in greater Minnesota. In Owatonna, a city of about 22,000, Allina Hospitals & Clinics is replacing the hospital there with a new facility expected to cost upward of $50 million. The hospital is being attached to a recently expanded clinic owned by its competitor-turned-partner, Mayo Clinic, which is headquartered down the road in Rochester.

David Albrecht, the hospital's director of operations, said parts of the building date back to 1931, and the facility "was largely inefficient" in a modern health care delivery system. Its emergency room was too small, patients lacked privacy and it "suffered from some image problems," he said. Though the facility needed upgrades, at some point "it becomes cost prohibitive to do repairs," Albrecht said, so the facility decided to team up with Mayo on the joint hospital-clinic venture. Ground is expected to be broken on the hospital in the spring, with completion slated for 2009.

Out with the old (buildings, not people)

What's behind all the projects, renovations and new equipment? According to industry sources, a multitude of factors are driving health care capital spending, but the main ones include aging facilities, increased patient demand, competition and new service opportunities created by technical and other health care innovations.

Had you walked into the old Stanley Community Hospital in rural North Dakota, you would have been able to spot facility problems quickly. Originally built in 1950, it was expanded three times, but some things were never made right. The hospital opened with two floors, with most of the patient care on the second floor. But it never had an elevator, and a hydraulic lift for gurneys and wheelchairs "didn't work real well in our cold climate at times. When it was 30 below, the lift was real slow," said Leupp.

The Stanley hospital was like most, particularly in rural areas: built sometime between the late 1940s and early 1970s thanks to the Hill-Burton Act of 1946, which provided federal grants and guaranteed loans to improve the condition of the nation's hospital system. Between 1947 and 1975, some $6 billion in grants and loans were doled out to 6,800 health care facilities. In terms of scale, construction spending as a percentage of total health care spending peaked at about 13 percent in 1965. Today it's about 4 percent.

Ahrens, from the Montana Hospital Association, said most of the state's rural hospitals were built in the Hill-Burton era. Now those facilities are reaching the end of their design life, "and they should all be rebuilt." Easier said than done, and Ahrens knows it. "Small hospitals don't have the financing. They cobble things together by hook or by crook."

Rural hospitals have received a big lift from the federal Critical Access Hospital program, which reimburses designated rural hospitals at a higher rate for Medicare services that it does for all otherhospitals. The program has been particularly important in terms of revenue because many rural hospitals have an older patient base, and Medicare makes up a disproportionate share of revenue—in some cases, 80 percent or more.

Sources across the district roundly applauded CAH as a savior for rural hospitals and considered it largely responsible for the capital improvement activity that has been taking place. Quinn, from the WHA, said rural Wisconsin hospitals "have seen a tremendous uptick in activity in recent years" in the CAH program, adding that "a lot of them have plans" for building improvements.

CAH has helped hospitals dream about improvements again, said Ahrens, from Montana. "Before (CAH) happened, they couldn't even think about it."

(A more detailed look at the Critical Access Hospital program will appear in a future issue of the fedgazette.)

Party of one, your room is ready

Higher patient demand is also putting pressure on old facilities, and as baby boomers begin moving to senior-citizen status, demand for health care is expected to rise across the board in the future. Over the past two decades, there have been strong shifts in the care model, most notably a rapid increase in outpatient care. In the past, if you had cancer, "right away you were admitted" for a long stay in the hospital, said Leupp. Today, it's all outpatient.

That shift creates a parallel need for a different use of space than older facilities can easily accommodate; rather than beds, growing numbers of outpatients demand more exam rooms, better diagnostic facilities and equipment, and even bigger waiting rooms.

But about a decade ago, inpatient admissions—the real moneymaker for hospitals, especially in terms of patient visits—also started inching up after a long period of decline. Inpatient admissions rose about 15 percent from 1994 to 2004, according to the American Hospital Association. In Wisconsin hospitals, inpatient admissions increased 5.6 percent from 2001 to 2005, complemented by 20 percent growth in outpatient services over the same period, according to the WHA.

At the same time, research is finding a link between facility design and inpatient care outcomes, which adds to the building wish list. A good example is the move toward private, single-patient rooms. The current remodeling and expansion of Regions Hospital in St. Paul includes 180 private rooms. In Helena, Mont., St. Peter's Hospital is in the midst of a $43 million renovation and expansion, including a conversion to private rooms. The new hospital in Owatonna is also slated to have all private rooms.

The reason is simple: improved health for patients, according to Albrecht, from the Owatonna hospital. "There's evidence you can cut down on infection rates" with private rooms, and greater privacy allows for better rest for patients and more convenience for their families, he said.

But there's also the matter of hospitals charging more for single rooms, and some critics believe that the all-private trend is fueling an already heated battle among health care providers for high-end patients.

An article last year in Health Affairs, a trade journal, acknowledged that although the private-room trend "partly reflects" concerns about infections and patient privacy, "by and large, it reflects hospitals' desire to provide a potentially costly patient amenity to attract or maintain business."

Planned obsolescence

For all the capital projects going on in the district, the honey-do list doesn't always get much shorter. For starters, hospitals suffer from low margins, which have pushed capital investment toward projects targeting high-margin procedures and patients. (See "You are what you reimburse".)

Compounding the low margins is the fact that there's just more stuff to buy these days. Innovations in medical imaging and information technology, for instance, create new capital needs where there were none before (see "The next IT in health care"). The pace of health care innovation today also means that the shelf life of new investments is a fraction of what it was when Hill-Burton hospitals began dotting the landscape.

Redfield, from the Minnesota Hospital Association, said many organizations lease medical equipment rather than buy it. But even when a five-year lease is up, "you're two years behind" on the latest technology, Redfield said.

So despite the flurry of activity this decade, it's hard to keep up with capital requirements, including the need for new buildings. The average age of hospitals has still been trending up, from 7.9 years in 1990 to 9.8 in 2004, according to HFMA. In North Dakota, the average age is 12.4 years. "We've got a lot more depreciating facilities than (elsewhere) in the country," said Thomas, from NDHA.

In some ways, there is both more and less pressure for rural hospitals in terms of capital investment. Most have long accepted the idea that they can't be all things to all patients. Provide the basics, and do them well, and nurture relationships with the big metro hospitals to refer and transfer patients. "All they are trying to do is keep their patient base," said Redfield. That means keeping facilities "new enough so patients don't go elsewhere."

Still, low margins mean a constant struggle to find extra dollars to pay for capital improvements. In the life-and-death field of health care, immediate needs tend to take precedence over future ones, which can turn into a vicious circle. Thomas—and many other sources—said that capital expenditures are first on the chopping block "if you're in a financial pressure cooker." Putting off improvements is often simply the easiest—or only—budget option, but it's not without consequences. Thomas said that deferring building improvements "is a long-term signal of concern" because at some point patients decide to go elsewhere for more modern services and facilities.

So it's damned if you do, but probably doubly damned if you don't. Beyond improving patient care, modern facilities and equipment help to attract and retain staff, especially in rural areas. Fifteen years ago, the idea of having computer-assisted diagnostic imaging "was very remote," Thomas said. Today, it's a must-have because "it's considered a top recruiting tool for doctors."

David Hewett, president and CEO of SDAHA, pointed out that once a technology is in the marketplace, "specialists demand it." Hospitals and clinics have to realize "that if they want to recruit physicians and attract patients, they'll have to pay attention to their physical plant."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.