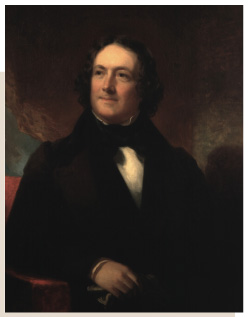

When the Second Bank of the United States was at the height of its power, wrote the Inquirer newspaper of Philadelphia in February 1844, “no man was more courted or eulogized” than its president, Nicholas Biddle.1 The Inquirer was being kind; years removed from his heyday, Biddle had just died in utter disgrace.

A renaissance man accomplished in literature as well as finance, Biddle was the country’s first central banker, and he was a master of his craft. Under his firm direction, the Second Bank grew into a powerful instrument of monetary stability, the rock upon which a decade of robust economic growth was built. But for all his financial brilliance and managerial skill, Biddle had faults that proved to be fatal for the Bank and his career. Arrogant, hypersensitive to criticism and unschooled in politics, he failed when put to the test during the vitriolic battle between Biddle and President Andrew Jackson over the rechartering of the Bank.

Few who met Biddle as a young man doubted that he would go far. Son of a successful Philadelphia merchant, he graduated from Princeton University at the age of 15, at the top of his class. While still a teenager, he served as secretary to the U.S. minister to Napoleonic France, working on the financial details of the Louisiana Purchase. Later he was secretary to James Monroe, the U.S. minister in Britain and future president. Admitted to the bar, he showed more interest in letters than the law, preparing the journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition for publication and editing the Port Folio, an influential literary magazine. Marriage to an heiress allowed him to indulge his fascination with ancient Greek culture on a huge estate outside Philadelphia.

Biddle was also interested in banking and the economy. In 1811, as a newly elected member of the Pennsylvania Legislature, he spoke in favor of a new federal charter for the First Bank of the United States, which many state lawmakers opposed. In a speech that has been called “the maturest expression of banking knowledge to be found in America in that period,”2 Biddle argued that the First Bank was constitutional and crucial to the economy as a repository of wealth and issuer of uniform currency.

The speech established him as an authority on banking, currency and government finance, and when in 1819 President Monroe was looking for a new government director to help manage the troubled Second Bank, he picked Biddle, his former secretary and friend. Bright, strong-willed and articulate, Biddle quickly became one of the Bank’s most influential directors. Committed now to a career in finance instead of literature, he quipped in a verse written for a young admirer that: “I prefer my last letter from Barings or Hope/to the finest epistles of Pliny or Pope.”3

Biddle became president at age 37—younger than most of the directors who elected him—and immediately put into action his plan for developing the Bank into a great balance wheel of the monetary system. Biddle was “the prototype of the modern business executive,”4 a manager who could both formulate bold ideas and execute them by delegating to handpicked subordinates.

Those talents proved inadequate, however, when Biddle was thrown into the political cauldron that Jackson stirred up during the Bank War. He had personality flaws that worsened the conflict and drove him to take extreme measures to save the Bank. Biddle was excitable, self-important and compulsively defensive about the Bank and his image. “[H]is feelings never got the better of his manners but often marred his judgment,” said banking historian Bray Hammond.5 Moreover, he was politically inept, overplaying his hand at pivotal moments of his struggle with Jackson.

Biddle exasperated the president by his repeated refusal to seriously investigate charges of political interference by some Bank branches during the 1828 elections. And he squandered what might have been opportunities for rapprochement with Jackson, brushing off his allegations against the Bank and antagonizing him by pressing ahead with recharter in 1832.

Stubbornness spilled over into recklessness at the climax of the Bank War, when Biddle used the Bank as an economic weapon and made inflammatory remarks about Jackson. “This worthy President thinks that because he has scalped Indians and imprisoned Judges, he is to have his way with the Bank,” Biddle wrote to a federal judge in February 1834.6 By the fall of that year, Biddle was so reviled for his nationwide curtailment of credit that he was hunted by mobs in Philadelphia, forcing him to bar the doors of his house and post armed guards.

Arguably, a more temperate and politically astute leader of the Second Bank would have found common ground with Jackson, resulting in a peaceful end to the Bank War and renewal of the Bank’s charter. It’s conceivable that if not for Biddle, the Bank would have stayed in business for decades, altering the course of banking history.

We’ll never know, of course; the Second Bank was destroyed, and out of its ashes Biddle formed the U.S. Bank of Pennsylvania, a commercial bank run under a state charter. In private banking, Biddle could not replicate the success and adulation he had enjoyed as a central banker. As president of the Pennsylvania bank, Biddle authorized risky loans and investments, and hatched a dubious plan to use bank funds to corner the market on cotton. After Biddle retired in 1839—briefly pursuing the U.S. presidency as a Whig running against Martin Van Buren—he and other former officers of the bank were indicted for fraud and theft in connection with the cotton scheme. The charges were dismissed, but creditors had lost faith in the bank, and it failed in the Depression of 1839–43.

The collapse of the bank consumed Biddle’s personal fortune and what remained of his reputation. Broke and shunned by old friends and associates, he retreated to his wife’s estate, where he died at the age of 58—heartbroken, according to his biographer, at the loss of the bank and his fall from grace.7

—Phil Davies

Endnotes

1 Thomas P. Govan, Nicholas Biddle: Nationalist and Public Banker (University of Chicago Press, 1959) p. 412.

2 Fritz Redlich, The Molding of American Banking: Men and Ideas (New York: Hafner, 1947) p. 110.

3 Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1957) p. 292. Baring Brothers and Hope and Co. were international banking firms.

4 Redlich, p. 118.

5 Hammond, p. 297.

6 Nicholas Biddle, The Correspondence of Nicholas Biddle, ed. Reginald C. McGrane (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1919) p. 222.

7 Govan, p. 411.

Return to: The "Monster" of Chestnut Street