There is a body of research showing that employers benefit from having financially savvy employees. In fact, data show that the better employees manage their finances, the more productive they can be. According to an award-winning doctoral dissertation submitted to the Virginia Polytechnic Institute by consumer behavior researcher So-hyun Joo, company profits increased by $450 annually for each employee who slightly improved his or her financial behaviors. The increase in profits resulted from reduced absenteeism and a decrease in work time spent dealing with personal financial matters.

These and similar findings have led many employers to provide workplace-based financial education workshops for their employees. In giving employees the information they need to manage money wisely, employers hope not only to increase productivity and profits but also to realize other proven benefits of employer-provided financial education, such as:

- Reduced ERISA (Employee Retirement Income Security Act) fiduciary risk. ERISA sets minimum standards for the retirement plans and health benefits private employers offer. Employees who make informed decisions in connection with pension and 401(k) plans are less likely to make claims under ERISA.

- Reduced reputational risk. Employees who feel that their employer is concerned about their personal financial well-being are less likely to voice negative opinions about the employer. Also, employees who succeed financially are less likely to be the basis for negative publicity. For example, imagine the effect on a company's reputation from just one news story featuring a former employee who is now bankrupt due to poor personal financial planning.

- Increased savings. Employees who have access to professional financial planning resources are more likely to take advantage of flexible spending accounts and other programs that reduce the employer's payroll taxes.

- Increased retention. Employees who feel that their employer is concerned about their personal financial well-being are less likely to leave.

- Increased flexibility. Employees who have access to professional financial planning resources are more likely to adapt well to relocation, termination, or other employment changes that have personal financial consequences.

It stands to reason that, in order to maximize the benefits of workplace-based financial education, employers should make the education accessible and relevant to employees. When the financial services giant Citigroup (Citi), working in partnership with the professional services firm Ernst & Young, implemented a program of workplace-based financial planning workshops, it addressed a number of challenges related to access, relevance, and other matters. Citi's experience, described below, offers lessons that may help other employers deliver effective financial education programs of their own.

The main challenges

In 2004, Citi made a commitment to fund financial literacy projects around the globe for a ten-year period. This commitment was accompanied by a promise to spend a minimum of $200 million and establish an Office of Financial Education (OFE) to help coordinate the effort. The funds would be directed to nonprofits that would then drive the dissemination of financial education.

Meanwhile, as Citi's OFE and the global financial literacy effort took shape, a group of senior managers involved in the project began turning their attention to financial literacy on a much more local scale. They communicated to the OFE their interest in expanding the financial education offerings Citi made available to its employees. A financial education program consisting of phone consultation and online advice was already in place at Citi, with Ernst & Young providing the phone component and the investment advisory firm Financial Engines providing the online component. The senior managers who approached the OFE wondered if in-person, instructor-led training on personal finance would be useful to employees. They proposed bolstering the existing financial education program by adding a workshop component.

The OFE soon found there were several major challenges that Citi needed to address in order to move the proposed workshops forward.

Challenge 1: Overcoming management skepticism. There was a consensus among the early discussants that making the proposed financial education workshops mandatory would not be probable or even possible. But, if workshops were entirely optional, would employees attend? Since Citi is a financial services company, there was a tendency among some members of management to believe that employees would already have a high financial literacy level and therefore workshop-style education in the elements of personal financial management would not be necessary. Even if there were a need for the workshops, there might be an embarrassment factor that would keep employees from attending the sessions. Also, would bosses give employees time away from their assigned duties? If participation was not adequate, would the time and expense have been better spent on something else?

Challenge 2: Determining whether to keep the training in-house. Citi knew that the expertise existed within the company to train employees internally, but mustering the manpower needed to reach employees in numerous offices throughout the United States was a challenge. And if Citi committed its employees to provide the training, which of the corporation's businesses—such as Citibank, Citi Cards, or Smith Barney—would they come from? The effects on the businesses' bottom lines was also a consideration, since none of the businesses had previously included this expense in their operating budgets. The costs involved could be significant, after adding in expenses such as content creation, facilitator training, and travel. Also, Citi would have to cover the costs of replacing the employees who were shifted from other duties or hiring new employees to fulfill this new function. Finally, what would the legal implications be if Citi employees offered financial education to other Citi employees? Would the education be construed as advice? If employees who attended the training saw their financial situations worsen, would this open Citi to legal consequences?

Challenge 3: Ensuring the program's effectiveness. Before it committed to implementing financial education workshops, Citi wanted to design a way to ensure that the program would make a difference. Would it lead employees to change their financial habits, and would the resulting changes improve the employees' financial wellness?

Challenge 4: Meeting the needs of a huge, diverse work force. Citi is one of the largest financial services companies in the world, with a global work force of more than 300,000 people of different ages, education levels, job functions, and cultural backgrounds. In North America alone, Citi has more than 100,000 employees. How could one program of workshops meet the needs of such a large and diverse work force? Could Citi build in enough flexibility to make the workshops broadly useful to such a group?

Moving the program forward

The OFE and the pro-workshop members of Citi's senior management moved to address each challenge in turn. First, the OFE took action to counter some Citi managers' skepticism about demand for and participation in financial education workshops. The OFE was confident that demand for the sessions would be strong. After all, the skills required to work in finance do not automatically translate to understanding the world of finance on a personal level. An employee who is an excellent bank teller might not be knowledgeable about creating a personal financial plan, for example, or an employee who is adept at processing credit card applications might not be familiar with the concepts of prudent debt management.

To demonstrate that this type of education was desired, the OFE created two basic, brown-bag workshops to be delivered to Citi employees—one on credit management and the other on money management. Over the course of a year, the OFE delivered the workshops in approximately half a dozen Citi locations across the United States where there were significant numbers of employees, such as Dallas; St. Louis; and Wilmington, Del. The workshops were conducted during lunch time and were entirely optional. Communications used to attract employees to the workshops ranged from posters in the break rooms and elevators to promotional messages sent through interoffice channels such as closed circuit TV and e-mail. The OFE and the pro-workshop senior managers used conference calls to encourage other Citi managers to publicize the workshops and allow employees to take an hour out of their workday to attend. In most cases, the workshops were offered during mealtimes in order to lessen the time employees were away from their job functions.

The OFE found that attendance was better than anticipated. In fact, at the CitiFinancial International headquarters in Texas, the sessions had to be moved from a conference room to the building's large atrium in order to accommodate all the employees who were interested in attending. Coupled with the strong attendance results were evaluations that overwhelmingly supported the concept of workshop-based financial education for Citi employees. Employees not only gave the workshops high marks but also asked for more. This evidence was enough to convince Citi's senior management to move forward on further developing the workshop program.

Next, Citi addressed the crucial matter of who would provide the training component of the program. After considering the costs and risks of using internal trainers, Citi's senior managers decided to look outside the company. Ultimately, Citi chose Ernst & Young, based on its existing relationship with Citi, its broad geographic reach, and its extensive experience in providing group training in workplace settings. Citi also felt that Ernst & Young, as an outside entity, would be a neutral advisor and less prone to conflict-of-interest concerns.

In order to address the next major challenge, ensuring the program's effectiveness, Citi decided to conduct a pilot of Ernst & Young's workshops. With input from local human resource leaders, Citi selected workshop topics from a comprehensive list of the workshops that Ernst & Young conducts for clients. Ernst & Young then customized its standard workshop content to reflect Citi's applicable benefit plans and programs. Four different employee sites, each located in a different state, were selected to test the workshops' effectiveness. The sites were chosen for having the lowest levels of employee participation in Citi's 401(k) plan. Afterward, the employees completed a series of evaluations that tracked the effects of the educational sessions on their financial behavior.

Citi found that after the workshops a significant percentage of attendees reached out to Ernst & Young's phone line for individual counseling. Also, there was an increase in the percentage of employees who started contributing to the company's 401(k) plan. The increase indicates that the workshops not only educated employees but motivated them as well. In addition, the tracking found that of the employees who were already contributing to the 401(k), a significant number made some changes, such as increasing the percentage that they contributed from each paycheck or modifying the composition of their investment portfolios.

Based on these positive findings, Citi's management agreed to start a financial education workshop program at about a dozen sites that had the largest number of Citi employees in the United States. Each site was allowed two eight-hour days a year to offer the workshops to its employee population.

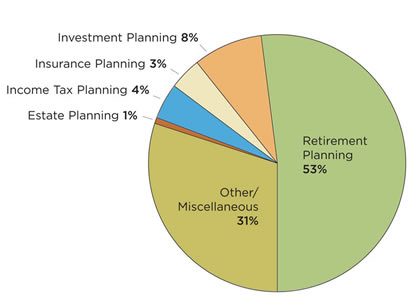

To accommodate the needs of a large, diverse work force that spans a spectrum of jobs, from bank tellers to managers of complex investment instruments, Ernst & Young offered a tremendous variety of workshop topics, from introductory sessions on money management to more sophisticated topics like estate planning. Other topics included investing, retirement planning, education funding, income tax planning, and insurance planning. Basic and advanced versions of most topics were offered. Citi's OFE surveyed employees at each workshop site in advance in order to determine the most relevant personal finance topics for the given location. The workshops that generated the highest interest were selected.

Ernst & Young worked with Citi on making the eight-hour period flexible to accommodate work hours that did not conform to a traditional workday. Many of Citi's operations were on a 24-hour schedule. Ernst & Young responded by allowing each trainer to be available for an eight-hour period, regardless of when the eight-hour window of time started or ended. Each eight-hour period offered the workshops at multiple times and with a menu of the most popular topics.

The reviews are in

Following the initial rollout to a dozen sites, the Citi financial education program grew, both in the number of sites and the total number of employees who attended. By 2008, the third and final year of the program, the number of sites expanded to more than 50 and the number of attendees was approximately 8,000. Citi has not tracked how the program affected the behavior of the expanded population of attendees, but it does have data on how the attendees viewed the program. According to reports Ernst & Young provided to Citi's Employee Resources function, which had overall responsibility for the financial education program, employees had high satisfaction with both the workshop and telephone counseling components. The reports reveal that when Citi employees were asked to rate the program's effectiveness on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest), their responses averaged a remarkable 4.7 rating. When asked whether the program enabled them to make a decision or take action, 92.8 percent of participants responded positively. Asked if they would use these services again or recommend them to coworkers, 97.7 percent responded positively.

The positive reviews suggest that Citi's approach to implementing financial education workshops may be a useful model for other employers to follow. By working with a trusted partner, conducting small-scale tests to demonstrate the workshops' effectiveness and garner management support, and building flexibility and choice into the workshop schedule, Citi found a way to make financial education work in the workplace.

William J. Arnone is a partner emeritus at Ernst & Young LLP. Dara Duguay is a former director of Citigroup's Office of Financial Education. For more information on the Citi–Ernst & Young partnership, e-mail Duguay at dara@daradollarsmart.com. For links to additional financial education resources from Duguay, visit her web site at www.daradollarsmart.com.

Retirement planning is #1What topics are likely to be most in demand in a workplace financial education program? The breakdown of calls made to the phone consultation component of Citi's financial education program provides some indication. As the chart illustrates, retirement planning was by far the most popular topic, accounting for more than half the calls placed to the Ernst & Young financial planning line. Retirement planning topics of most concern to Citi employees included their 401(k) plans, their pension plans, and IRA rollovers. The last item was of more concern to employees who were terminating their service with Citi. The most popular nonretirement topics included investment asset allocation; health and life insurance; beneficiary designations; estate taxes; wills and trusts; income tax penalties on early withdrawals; income tax withholding; debt, credit and budgeting; and loans.

|

For more informationThe resources described below provide additional insights into aspects of workplace-based financial education. Research findingsNumerous studies discuss evidence about the benefits of workplace financial education. For example, a 2009 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City and the U.S. Department of Agriculture summarizes recent research on workplace financial education and presents additional evidence from a new study conducted by the report's authors. See Weighing the Effects of Financial Education in the Workplace. Findings of the new research discussed in the report were highlighted in an October 2009 Minneapolis Fed webinar. Federal and nonprofit resources

Opting out instead of inIn recent years, employers have begun supplementing their workplace-based financial education offerings with efforts that make it more convenient for employees to build savings. Notably, many employers have changed from requiring employees to ask to enroll in 401(k) and other retirement savings plans (the "opt-in" model) to automatically enrolling them unless they request otherwise (the "opt-out" model). This simple change has been shown to significantly boost the rate of employee participation in workplace retirement plans. Evidence in support of the opt-out model is discussed in the May 2007 Community Dividend article "Aim of Pension Protection Act is to increase personal retirement savings." Ninth District initiativesNinth District employers have taken some noteworthy steps in implementing workplace financial well-being programs. In Minnesota, the Itasca Project, an employer-led alliance that addresses regional competitiveness and quality-of-life issues, triggered a workplace financial education initiative called Financially Fit Minnesota. Its development and recommendations are summarized in a Center for Financial Services Innovation report titled Employer-Based Collaboration: Lessons from Financially Fit Minnesota, available at www.cfsinnovation.com. In 2008, South Dakota adopted legislation that phased in the opt-out model for new-employee enrollments in the Supplemental Retirement Plan (SRP) for state workers. A report on the change, titled Adopting Automatic Enrollment in the Public Sector: A Case Study of South Dakota's Supplemental Retirement Plan, reveals that the opt-out model boosted SRP participation among employees from 20 percent to over 90 percent. |