The Quick Take: The trend in “reshoring”—bringing previously offshored manufacturing production and jobs back home—is widely heralded, but poorly documented. A growing number of anecdotes and other evidence suggest that some reshoring is occurring, particularly for items destined for domestic markets, the result of rising overseas production costs and better recognition of hidden costs and logistics issues. But reshoring’s effect on manufacturing employment in the district is likely very modest given the high-automation, low-labor demands of most reshored products.

The small community of Jackson, Minn., might not be the first place you look to see global manufacturing trends at work.

Tucked along the bottom of the state near Interstate 90, the community of 2,800 people might be more renowned for an odd pairing of American artifacts: Fort Belmont, one of only two civilian-built 19th century forts ever constructed in the Midwest, and Jackson Speedway, where all varieties of hobby and modified stock cars and other vehicles race around a half-mile dirt oval for purses of up to $10,000.

But in the northwestern part of town, in the city’s industrial park, sits a new addition to a heavy manufacturing and assembly plant owned by AGCO, an ag-equipment giant with worldwide operations, headquartered in Duluth, Ga. The 600,000-square-foot facility has traditionally made self-propelled field sprayers and a variety of track- and center-pivot tractors. Some production has come through consolidation, as AGCO acquired other ag-related companies over the past two decades and brought that production to Jackson, eliminating jobs in other Minnesota communities along the way.

But earlier this year, about 100 new workers started assembling high-horsepower Massey Ferguson and Challenger wheeled tractors—products the company had been making in Beauvais, France. Tractor components—almost everything short of the wheels and batteries—are mostly still made in France or elsewhere and then put in a kit and shipped to Jackson for assembly.

That might not sound like a particularly economical way to build tractors, but Greg Peterson, the company’s director of investor relations, explained that these tractors were destined for U.S. farmers anyway, and “it’s cheaper to ship parts because you can put them in a container,” which takes up less space than a fully assembled tractor. Peterson said there are also savings in wages and benefits; workers in Jackson receive about 10 percent to 15 percent less in total compensation than workers in France.

“After all the puts and takes in a financial sense, [the production transition] is a wash,” he said. The company expects to reap additional financial benefits over the next few years as it looks to produce many components in the United States, possibly even in Jackson.

Welcome to manufacturing’s updated math, which is generating a growing number of anecdotes about firms like AGCO bringing manufacturing back to the United States. The phenomenon goes by a variety of names—reshoring, homeshoring, inshoring, insourcing—and happens in different ways. Corporations can return in-house production from international plants to domestic ones; or they might source such production to outside firms, giving contracts to U.S. vendors rather than those in other countries.

There are myriad reasons for doing so, but most center on the narrowing gap in labor costs between domestic and international locations, better recognition of indirect costs and logistics issues with overseas production and even the marketing opportunity to stamp “made in the USA” on products.

The extent of reshoring is guesswork because hard data are nonexistent. There are enough anecdotes to suggest that reshoring is occurring, giving rise to the hope of renewed manufacturing growth across the Ninth District and the nation. But reshoring is likely to have a limited effect, especially on employment, because factors that made offshoring a global phenomenon are still present, especially for low-value products requiring lots of labor.

However, a shrinking gap in labor costs combined with other considerations—transportation costs, customer service needs, supply chain logistics—have made it feasible for manufacturers to produce more goods domestically, especially those with a high level of specialization and automation.

Workers readying an engine at the AGCO plant in Jackson, Minn.

Manufacturing boom(erang)

A host of private surveys suggest that many companies are giving reshoring some consideration. Last April, the Boston Consulting Group found that more than one-third of U.S.-based manufacturing executives at companies with sales greater than $1 billion are either planning or considering reshoring some production back from China.

Another survey released in July by CoreNet Global, an association of corporate real estate executives, reported that 51 percent of corporate real estate asset managers expected a rebound in domestic manufacturing from offshore locations. This recovery will be driven both by companies bringing manufacturing plants and jobs back to the United States or by choosing not to offshore in the first place, according to the report—a trend it said “will continue strongly through the year 2020.”

MFG.com, an online marketplace for manufacturers, found that 40 percent of almost 260 small manufacturers surveyed said they had received a contract that was previously sourced to a foreign supplier. In earlier research by the organization, 22 percent of product manufacturers reported returning a portion of their production back to North America, and 33 percent were researching such a move.

But the full extent of reshoring is hard to put your finger on. There are no reliable counts of reshoring activity at virtually any scale, not even back-of-the-envelope estimates to quibble over. “We’ve been asked that question a lot in the last year or two, but I’m not aware of any numerical studies,” said Neal Young, director of economic analysis at the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development. “Everything we’ve seen has been anecdotal.”

And there are plenty of reshoring examples. You can’t get any more American than softball, the “ting” of batted balls echoing across virtually every community in the country—and sometimes all the way to China. That’s where bats from Miken, based in Caledonia, Minn., were outsourced about eight years ago. But last year, the company decided to return production to Caledonia.

The company declined to be interviewed and hasn’t disclosed employment changes in Caledonia, but said via email that it “regularly reviews its supply chain and manufacturing costs, and in doing so, we made the decision to move some of our manufacturing back to the U.S. from China.” Specifically, costs had risen in China, and the return to local production allowed the company “to tap into a high-quality labor market, while improving our supply chain logistics at lower manufacturing costs.”

Miken’s experience underlies a fundamental driver of reshoring activity. Overseas manufacturing costs—especially in China—have been rising. Boston Consulting Group estimated that Chinese factories were seeing wage and benefit increases of 15 percent to 20 percent per year, one reason it believes the United States will be “in a strong position” to gain 2 million to 3 million manufacturing jobs by the end of the decade.

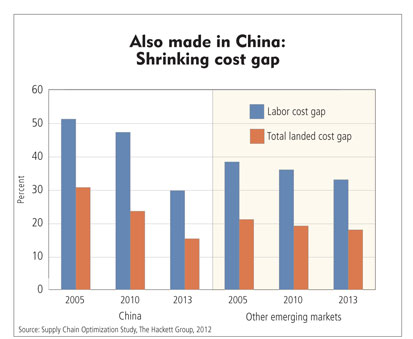

As overseas costs rise, the gap between domestic and international production has been closing. A study by the Hackett Group projected that the wage gap between the United States and China will fall from 51 percent in 2005 to 30 percent in 2013 (see chart, reprinted with Hackett’s permission).

But wages are only part of the story. Among other reports on the matter, Hackett’s study found that the gap in total landed costs—raw materials, component costs, transportation and logistics, inventory carrying costs, taxes and duties—have been halved from 31 percent to 16 percent, and similar cost reductions were also seen in comparison with other emerging, low-cost countries (see chart). These structural changes “are definitely permanent” under the most likely scenarios imagined by the companies tracked by Hackett, said Michael Janssen, the firm’s chief research officer, in an interview. “They expect the gap to shrink further. The only thing that changes is the time frame” in terms of how quickly things might occur.

District reshoring

Manufacturers in the district are seeing the cost-gap phenomenon firsthand. Jim Haglund, president of Central Container in Brooklyn Park, Minn., said he’s been going to China for 30 years. He’s watched productivity there steadily improve, but lately he’s seeing costs rise. “Inflation is hitting them, and workers are demanding more money.” Combined with higher transportation and other costs, the price gap is now closer to about 20 percent, Haglund believed. “Once you put pen to paper, it costs more” to be in China than many first realized.

Add in customer service needs—like quicker product adjustments—and more manufacturers have started to rethink their offshoring strategy. Haglund said Central Container is seeing business increase for contracts with medium- to lower-quantity volumes, where cost isn’t necessarily the overriding factor. His company now does more business with a high-tech stamping company (which Haglund couldn’t name for privacy reasons) that wanted better quality and quicker turnaround. “Where quality and inventory [control] and service are concerned, that’s where it’s coming back. Items that we lost eight or nine years ago, we’re getting back.”

It’s a similar story at OEM Fabricators, a Woodville, Wis., heavy-industry contract manufacturer. Customers are looking more closely at “time to market” from the prototype stage to final product rollout, and “many of our customers are accepting the concept that there are other important considerations beyond simply the price,” said President Mark Tyler. Supply chain control is also becoming more important, “and closer [proximity] typically means more opportunities to reduce supply chain costs,” he said.

Nicolet Plastics, a plastics injection molding company in Mountain, Wis., has also seen an increase in domestically sourced products, said President and CEO Bob MacIntosh. The company has embraced so-called quick response manufacturing to reduce the cost of producing low-volume, customized products. Along with immediate product savings, lower volumes mean less inventory for customers “as well as less chance of [product] obsolescence. If a customer is buying container loads of product from overseas, it had better be right when it arrives.”

Newly assembled field sprayers lined up at the AGCO plant in Jackson, Minn.

Producing goods closer to their final sales market offers obvious logistics advantages. It has the added perk of capitalizing on rising buyer preferences for goods made here. Peterson, from AGCO, said, “In marketing, there is a big advantage” to bringing the new tractor production to its Minnesota plant in Jackson. The company built a 17,000-square-foot visitors center in Jackson where, along with historical company and agricultural artifacts, visitors can get a glimpse of the assembly line so that “farmers can come in and see their tractor roll off the assembly line.”

A “positive” net zero?

Despite these positive developments for district manufacturers, the impact of reshoring is likely to be more muted than all of the anecdotes might imply, especially in terms of employment.

For one, the Chinese manufacturing dragon is far from dead. In June alone, the United States carried a $27 billion trade deficit in manufactured goods. Outsourcing to China and other low-cost countries will still be the way to go for many U.S. manufacturers producing goods that are even moderately labor intensive. “The advantage in China is still labor. … Its labor scale is unbelievable,” said Janssen. Apple, for example, is famous for employing huge numbers of foreign workers for manual tasks, like putting stickers on an iPad or putting it in a box. Such jobs are simply impractical in the United States, he said. “There’s not enough people in the U.S.” willing to do similar work for a comparable wage.

But Janssen noted that cost increases in China are real and not likely to go away soon. As factories there continue to pump out goods and earn profit, Chinese workers are asking for something in return—a normal transition in any growing economy. Workers there, Janssen said, “don’t want to live like peasants any more. They want the things we want,” like better living conditions and material goods. This leaves U.S. companies with three options: Increase labor productivity at Chinese plants, move production to lower-wage countries or bring it closer to developed markets.

But a lost job in China—or other low-cost country—does not equal a new job here. A plant in China with 100 workers might employ only 10 workers if it were located in the United States because the domestic plant—by necessity—would be highly automated to offset much higher wage and benefit costs, according to Janssen. Such capital investments are also easier today because of the low cost of capital.

Hackett’s research suggests something of a rebalancing in manufacturing production, rather than a reshoring stampede. A May report by the group found that companies are exploring reshoring for nearly 20 percent of their offshore manufacturing capacity between 2012 and 2014. While that’s a positive development for U.S. producers and their workers, this repatriated production would only “roughly offset the jobs that will otherwise move offshore, indicating that the great migration of manufacturing offshore over the past several decades is stabilizing.”

In other words, “the good news is that we’ve gotten to net-zero jobs. We’ve finally reached an equilibrium,” said Janssen. “That’s bad news for China. But unfortunately, [the resulting job growth here] is not as much as politicians would like.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.