Video: fedgazette Editor Ron Wirtz on the fiscal oil boom

By now, surely you’ve heard of the oil boom in North Dakota. You know: jobs aplenty, high wages, hefty royalty checks for landowners and crying babies.

Crying babies?

While many obvious economic benefits flow from the Bakken oil boom, it’s akin to a newborn baby, who brings excitement and joy to the whole family. But as any parent will attest, there is an awful lot of work involved, from constant feeding and diaper changes, to sleepless nights and an endless vigil over the little one’s health and safety.

In a similar way, local communities and the state Legislature are realizing that oil production and its concomitant economic activity and wealth come with a laundry list of things to fix and otherwise spend money on, such as crumbling roads, overwhelmed water and sewer systems, packed schools, and shortages of housing and community services like parks and emergency personnel that most people outside the region take for granted.

Connie Sprynczynatyk, executive director of the North Dakota League of Cities, likened the development challenge facing western communities to having a top-10 list of needs, “and all of them being number one.” And because oil and gas tax revenue flows first to the Capitol, the state Legislature “is like being a mother of 12 kids, and they all want attention.”

Fortunately, state coffers are overflowing from oil and gas tax revenue as well as strong growth—thanks in no small part to oil activity—in sales and income taxes paid by individuals and corporations. In the recently passed budget for 2013-15, total general fund spending is expected to reach $6.9 billion—almost 70 percent more than in the previous biennial budget.

“The state is in an enviable position because it can map its own course,” said Nancy Hodur, an economist at North Dakota State University (NDSU) who has done extensive research on the economic activity and effects of the oil boom. “There is tremendous opportunity for economic development if we do this right.”

But as is often the case, the devil is in the details. The challenge facing North Dakota is multifaceted. Local communities are begging for financial help to deal with the heavy impacts born from oil and gas development. The sheer scale of activity in the oil patch would itself be a challenge for any region, but it is compounded by the lack of capacity in this rural part of the state and by a state funding system in which the provision of resources to deal with oil-related development can lag on-the-ground effects by two years or more.

Over the past several legislative sessions, lawmakers in Bismarck have unhinged the lid on public spending and crafted a complex allocation system for oil and gas revenues to help local communities deal with immediate impacts while also setting money aside for rainy days, including ones well into the future.

Inevitably, despite the financial largesse, not everyone is happy. The biggest disagreements concern how much money is reaching oil-impacted areas. While such funding has steadily increased, “there is still a pretty significant shortfall. Communities need more help with critical services,” said Hodur. “The infrastructure is so undersized, you’d be hard-pressed to overbuild.” She noted that U.S. Highway 85 through Williston—the busiest road in the state, carrying “tens of thousands of trucks”—is still a two-lane highway. “It’s the deadliest road in the state.”

Many oil patch sources concurred with Hodur’s assessment. But the state also has to keep an eye on the future if it is to avoid the dreaded “resource curse,” where oil discoveries do more harm than good to local and state economies. That means state lawmakers have to worry as much about long-term economic development and diversity as they do about potholes and park benches. That makes for a lot of debate, as Sprynczynatyk has witnessed at the Capitol.

“You could ask six different legislators and get six different opinions” about how oil revenues should be spent, she said. “It’s an easier, shorter [legislative] session when there’s no money to spend.”

A heavy oil footprint

It’s easy to see the benefits of oil activity in North Dakota—unemployment rates are exceptionally low, wages are rising strongly and the area is awash in economic activity and, frankly, money. At an April conference, former Montana Gov. Brian Schweitzer called the Bakken “a millionaire maker.”

Given less attention—especially outside oil-impacted areas—are negative effects that have accompanied rapid oil and gas development in western North Dakota and eastern Montana. (Montana, for its part, has experienced much less of an oil boom and little of its fiscal benefits, but has experienced considerable impact as a result of being across the border from the Bakken’s core production area. See related fedgazette Roundup post.)

Development in the region presents bigger challenges for communities built above deep shale formations than comparable development near conventional oil fields. The widespread and capital-intensive nature of horizontal drilling and fracking brings more of everything—including more wells, which means more drilling, which means more equipment and supplies of every sort, transported on trucks that are multiplying like jackrabbits. All of this activity requires more workers, who need housing and other services in sparsely populated regions that are better equipped for prairie dog colonies than residential subdivisions.

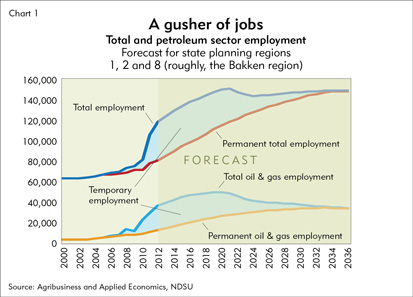

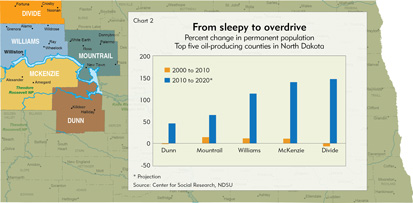

Already, the region has created tens of thousands of jobs in the petroleum sector and across the regional economy (see Chart 1). Populations are expanding as workers bring their families or make new ones. From 2000 to 2010, the population of Divide County—in the very northwestern corner of North Dakota—actually fell by 9 percent, to about 2,000. Assuming the current pace of development continues, the county population is projected to double by 2015, and then rise further to about 5,600 by 2020 (see Chart 2).

Sprynczynatyk said it was “difficult to make blanket statements” regarding community impact. “Some communities are overwhelmed. Some have the capacity to respond. All cities have some concerns about infrastructure. ...But because North Dakota hasn’t always been growing, the capacity isn’t there.”

What infrastructure is in place was designed to support a fraction of the activity in the region today. Roads, in particular, are taking a beating from convoys of trucks carrying water, frac sand and other supplies to hundreds of well sites. Last year, the Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute identified $521 million in road needs by the end of 2014.

And that’s likely just the tip of the oilberg. Dean Bangsund is an economist at NDSU who has worked on several recent Bakken impact studies with Hodur. He noted that the state had about 3,000 to 3,500 active wells before the boom. This spring, there were nearly 9,000, and that’s still just the warm-up phase. Estimates from the state Department of Mineral Resources suggest that the total well count will reach 40,000 to 45,000 over the next two decades.

“Now the gorilla is starting to roost. Now there are huge, huge development challenges,” said Bangsund. The physical demands and time scale—the breadth of things that need attention, and the time necessary to do them—“is something no one has dealt with.”

From Yay! to OMG!

There are several stages of community response to shale oil development, according to Richard Gardner, a consultant with Bootstrap Solutions of Boise, Idaho, and senior fellow at the Rural Policy Research Institute at the University of Missouri. He has done work for communities grappling with the effects of energy development from North Dakota to Pennsylvania to Texas.

Gardner said the first development stage is enthusiasm (we struck oil!), followed by uncertainty (is this for real?), then crisis (we need a plan) and finally adaptation (here’s the plan). “Sometime in the last year or two, there has been a transition from uncertainty to crisis,” Gardner said.

A population rise of 1 percent to 3 percent per year is considered robust, said Gardner. At 4 percent to 5 percent, “things are busting at the seams,” he said. “You’ve got McKenzie County growing 8 percent per year for the next 10 to 15 years. How can they possibly keep up?” In 1983, school enrollment in the McKenzie County School District was just over 1,000. By 2008, it had slowly eroded to 512. This year, enrollment is back to 868. February estimates by NDSU project school enrollment almost doubling by the 2016-17 school year to more than 1,600 students. In a very rural county, Gardner said, “they have low capacity in everything, and they can’t keep up with this.”

Oil patch communities also do not have the benefit of time, Gardner said. These communities “are suddenly doing a 180, and they are very rapidly being thrust from a sleepy community to an industrial region overnight.”

The response to the boom by individual communities is often uneven, depending on factors like staffing and financial capacity. As local communities race to expand infrastructure and other services, some “are bonded to the gills” and don’t have the capacity to take on necessary upgrades to city infrastructure, said John Phillips, a real estate project developer with Lutheran Social Services and former planner for the city of Beulah.

In January, a report commissioned by the city of Williston looked at infrastructure needs six years out. It identified more than $625 million in infrastructure upgrades, including $102 million for storm water, $110 million for drinking and wastewater and $259 million for transportation. The city was rewarded for that planning effort by having its bond rating lowered by Standard & Poor’s only months later over fears of projected budget deficits that could deplete cash reserves.

It’s even worse for small communities, because it doesn’t take much to overwhelm their capacity, and they get very little funding because formula-based state aid goes mostly to counties and regional centers like Williston and Dickinson. So they are left to hope that some aid passes down the ladder from the county, said Deb Nelson, manager, Vision West ND, a 19-county consortium of governments and other interests created expressly to help the region cope with oil impacts.

The city of Arnegard “is smack in the middle of the Bakken” with a population just over 100 people. But it has a service population of 1,600. “They don’t have public water; their sewer system is overrun and outdated. They were less than underprepared” for the deluge of service demands, said Nelson. “The needs are so much greater than the funding. Unless you’re here and experience it, you don’t have a good idea of what’s going on.”

Hodur, from NDSU, called western North Dakota “a socio-economic petri dish. There’s just a lot we don’t know” about the scale and impact of oil activity in the region and how to handle it in a way that will provide long-term local and state benefits.

Measuring the full impact of oil development, calculating the costs and planning the necessary community response “is a very difficult process to get your arms around and capture. The issues are bigger than any of us imagined,” said Nelson. Efforts to date have identified housing, transportation and roads, water, emergency services and day care as the most pressing needs. But the group has “not yet begun putting together the fiscal impact of any of the top five needs of our region,” Nelson said.

The process of identifying just the scale of needs is difficult, to say nothing of calculating costs or planning for implementation. The Upper Great Plains group identified $7 billion in necessary transportation investment over the next 20 years: half in oil-producing counties, half outside. While certainly useful, the number is bound to change; the group’s 2010 estimate for two-year road investments grew 50 percent by 2012, the result of an 80 percent increase in projected wells along with rising costs for gravel and pavement.

Estimating both current capacity and long-term need is challenging for any public service. For example, much of the region is served by volunteer emergency and fire services, and reports have shown that volunteer rates are down. “They are running into a large increase in calls, and it’s very difficult [for volunteers] to be called out constantly and still hold a full-time job,” Nelson said.

But figuring the cost of upgrading emergency response services across the Bakken region is a daunting prospect. Vision West conducted an initial study of emergency services to determine gaps and overlaps. This might sound simple, but the region is “so large and so very rural ... [that] we have not been able to put a financial cost to the needs because we haven’t been able to fully capture where the gaps are largest, and we haven’t yet been able to identify workable solutions for this huge service area,” Nelson said.

The group is bringing in experts to help study the matter and is holding a series of symposiums through October in hopes of coordinating regionwide improvements. “What we are experiencing is like drinking from a fire hose. We have to figure out how to make the hose smaller, lower the water pressure or drink faster—all before we drown,” Nelson said.

Gusher of tax revenue

The good news is that North Dakota is brimming with money to address many of its needs.

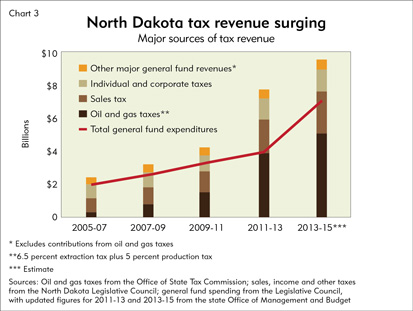

The role of oil in this is both obvious and subtle. Oil and gas tax revenue has grown at a Himalayan trajectory and comes from an 11.5 percent severance tax (see sidebar for explanation). As recently as the 2003-05 biennium, this tax tallied only about $120 million. It’s projected to top $5 billion during the 2013-15 biennium (see Chart 3). This amount doesn’t include royalty and other revenue from energy production on state-owned lands. In the recent biennium (through early March), this equaled $560 million.

Unbeknownst to many, however, very little of this oil and gas revenue goes directly to the state’s general fund, the budget base for government operations. In fact, the general fund can directly receive no more than $300 million per biennium. The rest is distributed through a complex—some might say byzantine—system of allocations that somewhat limits the Legislature’s annual decision-making over oil and gas revenues. Some of the money is automatically sent to city, county and tribal governments, while other funding goes to a host of priorities, including property tax relief, grant funding, rainy-day funds and long-term savings (see sidebar for more discussion about oil and gas revenue allocations).

Other state tax receipts are also surging (see Chart 3). Sales taxes and income taxes on individuals and corporations, which make up the lion’s share of the state general fund, have risen strongly in part from heavy direct and indirect spending that comes from oil development.

Add it all up, and a lot of tax money is flowing to Bismarck—a projected $9.5 billion for the 2013-15 biennium, triple the amount collected in 2007-09. Not surprisingly, general fund spending has swollen as well, to a record $6.9 billion for the coming biennium.

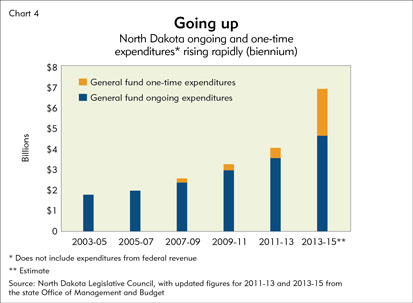

But the state has gotten in the laudable habit of squirreling money away in rainy-day and permanent trust funds (see sidebar on oil and gas tax allocations). It also has been cautious in committing to permanent spending programs, preferring one-time expenditures—much of it to deal with oil impacts—that are not automatically assumed into future budgets. In the span of four budgets, the state has gone from zero one-time expenditures to $2.2 billion in the upcoming biennium, according to state sources (see Chart 4).

Say when

How much of that money is reaching the oil patch to expressly deal with oil impacts is hard to determine exactly. But the easy answer is “more.”

In the spring, legislators passed a measure to spend more than $1.1 billion over the next two years for improvements to infrastructure, law enforcement and emergency services, with most of it going to the oil patch. Oil-impacted counties and cities will receive direct aid of $543 million—more than double the amount in the previous budget. The budget also includes $240 million for an oil-impact grant fund, almost double its previous allocation. The state’s highway construction budget for the next two years was approved at $878 million, or almost $290 million more than the previous record in 2011, with most of the money earmarked for the oil patch. Overall state spending is also significantly higher, so increases for K-12 education and other fundamental public services will also flow to oil country, though to what degree is hard to track precisely.

Sources inside and outside the oil patch seemed universally pleased to see increased spending in the oil patch. Keith Lund, vice president of the Grand Forks Region Economic Development Corp., pointed out that oil revenue has helped to lower individual and corporate income tax rates statewide and provided property tax relief. The 2013-15 budget alone has $850 million in property tax relief. Corporate income tax rates have been lowered in each of the past four legislative sessions; top rates have gone from 7 percent in 2006 to 4.53 percent.

Maintaining that revenue stream requires ongoing investment, he added. “There are a lot of needs out in the western part of the state, and it has to be supported or it just all stops,” Lund said.

But whether it’s enough is a hotly debated question. Most sources in the oil patch were unequivocal that recent funding increases—while very helpful—were still insufficient. Many still see needs unmet from previous state budgets. In the legislative sessions of 2009 and 2011, “we thought we had done things to address the oil impact. But it turned out to be woefully inadequate,” said Senate Minority Leader Mac Schneider (D-Grand Forks). “We weren’t even playing catch-up.” Even given the big increases in the newest state budget, “we’re not under any delusions. This is not a cure-all [budget],” he said.

Oil patch advocates point out that direct aid to areas impacted by oil is still comparatively low despite the recent increases. In the early part of the decade, the percentage of oil and gas tax revenue sent back to producer counties averaged in the low teens. It increased to 17 percent in the 2011-13 budget and will increase to 21 percent in the coming two years, according to Pam Sharp, director of the state Office of Management and Budget. However, oil patch legislators like Rep. Bob Skarphol (R-Tioga) have pointed out that the state sends 35 percent of coal tax revenues back to producer counties. Sharp confirmed the estimate and said it might be conservative.

A report last year by Headwaters Economics of Bozeman, Mont., pointed out that North Dakota “stands out among its peers for providing the least direct funding for oil-impacted communities.” Local governments in Colorado, for example, receive 63 percent directly; in Montana and Wyoming, 39 percent and 35 percent, respectively, according to the report. While direct aid is climbing and “fills an important gap,” the report said, “leaving impact assistance to the discretion of state legislatures is not a responsible approach to managing an energy boom.”

Because of its sovereign status, the Three Affiliated Tribes was receiving a slightly larger portion (20 percent) of tax revenue from production on the Fort Berthold Reservation than nonreservation counties and cities received over the same period. The state is renegotiating the compact, and revenue sharing is expected to reach a 50/50 split.

Could you send it yesterday?

The timing of funding has also become a major sticking point for oil patch communities.

Once oil and gas are produced—and thus taxed—there has already been considerable damage done to roads and pressure put on other infrastructure and public services. But the funding intended to mitigate those impacts has to wait for the next budget cycle. That means cities and counties are getting money for impacts that happened years earlier.

“The whole political process lags the impacts,” said Bangsund, from NDSU, and delay is compounded by the fact that the Legislature meets every other year. “The response on immediate needs has not kept pace. There is a lot of entrenchment and inertia to get past. ... More needs to be done on a continual basis,” said Bangsund.

Shawn Kessel, Dickinson city administrator, was giving testimony at the Capitol during the spring session, and “one legislator, who shall remain nameless, came up to me afterward and said, ‘Shawn, I get it. Thank you. The light has gone on. You guys are making decisions today that are affecting you [financially] now. But you’re getting resources tomorrow.’”

Some governments are taking steps to help control development or at least prepare financially for it. Dickinson and many other cities have instituted impact fees on new housing developments to help with road and other associated infrastructure needs. Williston recently instituted a one-cent general sales tax to pay for a gigantic new recreation center and other planned improvements. But similar tax mechanisms are not easily available for many public services, like schools and law enforcement, and many small communities lack the staffing to implement and enforce impact fees.

Long term: Straight ahead or wrong turn?

In the rush of oil development and subsequent government reaction, many also believe that oil-impacted communities and the state have their heads too low to the ground, too obsessed with today’s needs to worry about long-term economic development and diversification.

Gardner, from Bootstrap Solutions, has done research showing the crowding out that can happen from oil activity, and it’s a story that resonates in the Bakken. Exploration, drilling and production bring many jobs. Labor shortages ensue, driving up wages. As workers migrate to well-paying jobs, housing becomes scarce, and the overall price of living goes up.

Meanwhile, base industries like agriculture and manufacturing are weakened as land and labor become more expensive and more pressure is put on water and road infrastructure. High costs and lack of affordable housing also stifle the development of secondary, non-oil-related professional and service industries that would normally emerge to serve a growing population with considerable discretionary income.

“In the short term, that has the effect of crowding out the lower-wage end” of the economy, not only retail but other service jobs not normally considered lower wage, like teachers and police officers, said Gardner. “The perverse result is an energy county can end up less diverse at the end than a non-oil county,” he said.

The phenomenon even has a name, “Dutch disease,” coined for the economic mania that followed the discovery of major oil and gas deposits in the North Sea near the Netherlands in the 1960s.

Bangsund, from NDSU, said the challenge for the state is figuring out how to avoid “lopsiding the economy” by ensuring that agriculture remains profitable in the region and that Dickinson retains the manufacturing base it had before the boom while facing strong wage pressures from higher-paying oil jobs. “The state is still far too reactive. ...It’s easy for the state to take its eye off that goal. ...We’re so enamored with current activity that we’re not having that [long-term] discussion.”

Sen. Schneider agreed that the state would benefit from some long-term planning and fretted that the state is not doing enough to “plan for life after oil. There was none of that” during the most recent session. He pointed to recent nonpartisan reports about the state’s future (North Dakota 2.0 and North Dakota 2020 & Beyond) that offer numerous recommendations about what the state can and should be doing. “We suffer from a lack of action, not from lack of a plan,” Schneider said.

That’s not to say the state has done nothing. It has a series of permanent and special-use funds that, at the very least, set aside a growing pot of money for future needs, however defined by future legislative sessions (see sidebar on oil and gas allocations). One of the most far-reaching is the Legacy Fund, a permanent fund set up two years ago that has about $1.2 billion and was adding $80 million a month. This money cannot be spent until at least 2017, and any efforts to spend its assets must be approved by a two-thirds majority in both houses. (A separate fedgazette article is forthcoming on permanent oil trusts in other U.S. states, Alberta and Norway.)

Ultimately, assessing local and state progress in catching up with oil development is a big challenge because the state is undergoing an economic transition like none it has ever seen, one that is dynamic and hard to analyze. Almost unbelievably, the state is still on the leading edge of this boom. Oil production is projected to grow for the next 10 to 12 years—possibly doubling, maybe more—before settling into a slow, sustained downward slope. At least for a while, that means more of everything, good and bad.

Sources across the state repeatedly said clear progress has been made at the local level and (some admit grudgingly) at the Legislature. Many sources pointed to the state’s conservative nature, which often prevents sweeping moves in favor of more incremental ones. In due time, they said, more progress will be made. Whether it’s occurring at the speed and in the direction necessary to tap the full potential will be gauged in years and in the remainder of the oil and gas still to be pulled from the ground.

Wayne Biberdorf is the state’s energy impact coordinator, appointed by Gov. Jack Dalrymple in March of last year to improve coordination between western North Dakota communities and state agencies. “I keep the governor’s office updated with respect to the needs of local political entities,” he said.

In Biberdorf’s opinion, “Everybody’s picked up their game. There’s no doubt in my mind.” Places like Williston and Watford City have witnessed unprecedented economic activity, “and the scale at which they are ramping up [to meet that demand] is amazing.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.