The Quick Take: The recession has induced tighter budgets for many local governments. While payrolls have often been cut, governments have also employed a variety of strategies—cooperative agreements, compensation freezes, deferred maintenance and productivity improvements—to make budget ends meet. While most budget areas have been affected in some fashion, cutbacks on streets and other infrastructure could have consequences down the road.

Nobody likes a crisis. But oftentimes crises have a way of focusing the mind and clarifying some underlying, fundamental values.

State and local government budgets have come under considerable financial pressure in recent years—even before the recession in some states. Jeff Spartz, executive director of the Association of Minnesota Counties (AMC), said a tight budget has some silver lining to it because “it encourages you to see the most important things that you do. It’s a good thing to do occasionally. But we’re doing it chronically now.”

For local governments in particular, tight budgets have put many public services in the barber’s chair, with some getting a trim, others a buzz cut. Local governments are employing many strategies to make the numbers work and still provide service, including staffing cuts, contracting for services and “doing more with less” by seeking greater efficiency and productivity.

Not all local governments in the Ninth District are in the same fiscal boat because state economies have performed very differently over the past decade. Minnesota and Wisconsin governments have traveled the longest and hardest road; Montana and South Dakota have faced some rough sledding, but most of it has been recent. North Dakota’s strong economy, and resulting tax revenue, continues to defy trends virtually everywhere else. Most of the discussion that follows will focus on Minnesota and Wisconsin because those states gather considerably more data on local government spending than Montana or the Dakotas, and both have endured more fiscal stress over the past decade, which offers a larger window for analysis.

How tight the belt?

Local government budgets are determined by a variety of factors, like population growth, local real estate investment and property value appreciation. But many are also at the financial mercy of their state governments, which pass along considerable revenue aid (or not, as recent trends show), place mandates on many locally provided services and often limit the ability of those same local governments to raise local revenue (see cover article and sidebar).

In Wisconsin, local governments have labored under property tax levy limits for 10 years, and a property tax freeze for the past two years, said Richard Stadelman, executive director of the Wisconsin Towns Association. In three of the past 10 years, state shared revenue has also been cut. “It’s dramatic,” Stadelman said about local government finances. “Over time, it’s gotten tighter and tighter.”

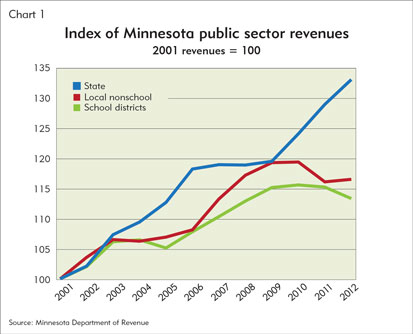

What has resulted is often a stark separation of (inflation-adjusted) spending growth between states and their local governments. In Minnesota, local government revenue has shifted lower after each of the last two recessions, while state revenue has maintained consistently stronger growth (see Chart 1).

Tight budgets have forced local governments to find different ways to keep the books balanced, from straightforward cutting to reorganizing departments and increasing taxes and fees to contracting for services and holding the line on employee compensation.

In Minneapolis, the city’s expenditures last year were about 20 percent lower than in 2009. Job cuts filled in much of the gap; the city eliminated 11 percent of its workforce (445 jobs) over this period. In anticipation of lower property taxes and federal and state aid this year, Mayor R. T. Rybak proposed further spending cuts of 3.4 percent. In announcing his budget, Rybak said, “Reform is not just an option, it’s a necessity. We simply don’t have the luxury of doing things the same old way.”

Harold Blattie, executive director of the Montana Association of Counties (MACo), said his member counties were facing milder budget challenges than peers in other states, but revenues nonetheless were “not keeping up with operational costs in virtually every county in our state.” Most counties have reacted by freezing current employee salaries or granting very small cost-of-living increases, he said, and keeping vacant positions unfilled longer.

Jeff Spartz, from AMC, noted that Minnesota counties have embraced so-called lean concepts—common in manufacturing—“that allow you to identify things that don’t add value,” like multiple workers and redundant tasks involved in a permit approval. “Most counties are looking to find ways of doing things more cost effectively.”

In mid-2011, the League of Minnesota Cities started a database of budget-balancing anecdotes from local communities, and it now lists more than 500 actions either taken or considered by cities of all sizes. “It contains a good range from the simple, low-hanging fruit to the more complex,” according to Rachel Walker, LMC manager of policy analysis, via email. The most common strategies identified—among a couple of dozen—involve contracting for services and doing more work cooperatively with other local governments, either formally or informally. Such strategies attempt to preserve service delivery while cutting back on employee wage and benefit costs, as well as equipment and other operational expenses.

That cooperative strategy appears to have gained some traction since the recession. A May 2012 report from the Minnesota Legislative Auditor found that cooperative agreements increased among almost 80 percent of responding counties and 40 percent of cities from 2005 to 2010; less than 1 percent said they had decreased. A Michigan survey last spring of local government officials found that 37 percent of respondents in the Upper Peninsula expected more intergovernmental agreements, and 10 percent expected increased privatization and contracting for services.

One common cooperative agreement deals with public safety, as many small communities resort to the once unthinkable—putting police and/or fire coverage in the hands of another entity. Since 2009, the city of Mound, Minn., had seen its tax capacity drop by 39 percent, causing its budget to fall as well. Cutbacks followed across virtually all departments, and full-time employees were cut from 50 in 2009 to 41 last year. Several job cuts came in the police department, whose 2012 budget still accounted for more than one-third of all city expenditures, according to city officials.

Faced with further budget troubles, in September, Mound disbanded its police department and contracted with the nearby city of Orono for police coverage. The city reported that the contract will save taxpayers about 10 percent in annual costs, or about $200,000, much of it coming from the elimination of the police chief’s position, which was officially vacant and being manned on an interim basis. None of Mound’s 10 full-time officers lost their jobs.

The move is not uncommon. In a police survey last year by the LMC, one-third of respondents (nearly 150) reported that police service provisions in their community had changed over the past 10 years, but the actions taken varied. The most common change (16 percent) was a reduction in staff, including paid officers, while other cities entered new contracts with the home county for law enforcement services and created new cooperative agreements with nearby cities. A total of 81 cities (18 percent of respondents) said they were currently considering such options.

Canosia Township in St. Louis County, Minn., might be completing the life cycle. More than a decade ago, it had its own police force. Tight budgets convinced it to contract with the county sheriff’s department. The township has not budgeted for future years, and “we are spending down the current balance. When this fund is exhausted, [the town is] not sure if we will do any sheriff contracting,” said Scott Campbell, the town board chairperson.

No money for brass tacks

When budgets get tight, priorities are often defined by the size of the cut because local governments appear to prefer an approach that spreads the pain widely.

The city of Waverly, a community of 1,300 located about an hour west of Minneapolis, has lost almost all of its state and federal aid over the past several years, forcing budget reductions of 13 percent from three years ago, according to Mayor Connie Holmes. The city lowered its property tax levy for 2013 by 3 percent in an effort to hold down property taxes. But a change in state requirements for calculating property tax capacity (and how taxes are allocated among property types) forced taxes on businesses to rise by 20 percent, and Waverly has lost businesses as a result.

Internally, the consequences for city services have been widespread. “All departments have had to cut … and our staff is doing more with less,” Holmes said. All work on parks was eliminated, and spending for general administration and staff overtime has been cut. “Street repair and improvements are not possible. … Snow removal [is] not as often, and other repairs on infrastructure [have been] delayed,” she said.

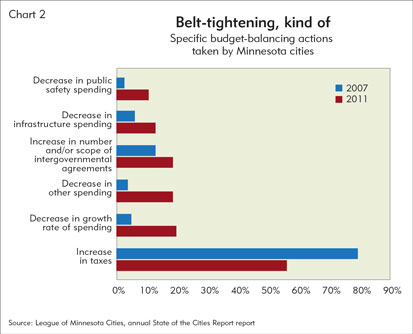

Other Minnesota cities appear to be taking a similar tack, according to an annual report on fiscal conditions by the LMC. To fill budget gaps from 2007 to 2011, cities depended less on raising taxes and more on decreasing spending—though cities were hardly going all in with either strategy (see Chart 2).

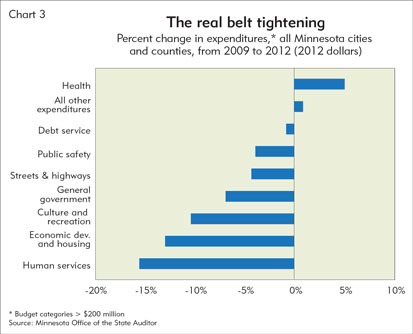

In terms of the services most affected, local spending reflects a “cut them all” approach. For Minnesota cities and counties, spending decreased virtually across the board from 2009 to 2012, according to data from the state auditor’s office (see Chart 3). The only area of increase came in health care spending, the large majority of which occurs at the county level and includes various health care services and clinics, as well as restaurant inspections, the collection of vital statistics data and communicable disease control.

Local government sources were reticent about all service cutbacks. But infrastructure seemed to be a central concern for many. “When times are tough, [infrastructure needs] tend to be the first” on the cutting list, because these cutbacks are not immediately noticed, said Dan Thompson, executive director of the Wisconsin League of Municipalities. “You fire a crossing guard at the school, and parents notice immediately. Cut back on road resurfacing, and the average citizen doesn’t notice. But 10 years from now, you’ll have a serious problem.”

Roads and other infrastructure didn’t necessarily see the biggest spending cuts. But they are unique among many public services because they come with spending tails in the form of constant maintenance, and failure to keep up can create backlogs that get proportionately more expensive over time, like the leaking roof you let go for too long, causing eventual damage to your home.

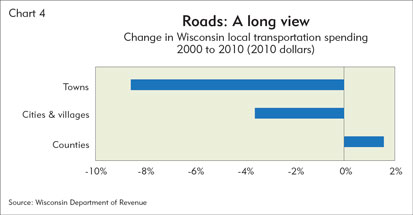

Yet general road spending has been flat or declining in many places. In Wisconsin, inflation-adjusted road and highway spending (including current expenditures and capital outlays) by local governments fell by 3 percent from 2000 to 2010 (the most recent figures), with townships and municipalities sustaining the worst cuts (see Chart 4), according to figures from the state Department of Revenue.

“Highways aren’t as good as they used to be. We see [towns] back off improvements, and as a result you have rougher roads and more potholes,” said Richard Stadelman, head of the Wisconsin Towns Association. “The problem is compounded by increased traffic from heavy farm and other machinery, including more trucks carrying multiple loads of frac sand destined for oilfields,” prematurely aging inadequately maintained roads. At the same time, federal and state gas taxes are not generating the same amount of revenue to be shared among highway agencies—the result of more fuel efficient vehicles and less driving due to higher gas prices. “There are greater needs, but less funding,” Stadelman said.

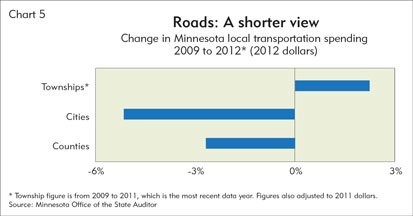

Minnesota offers a more recent picture of road spending, and it’s similar to Wisconsin’s. From fiscal years 2009 to 2012, total real road and highway spending in Minnesota fell by about 3 percent, with townships faring somewhat better and counties a bit worse than their easterly neighbor (see Chart 5). There is parallel evidence of slowly deteriorating roads. A Minnesota state transportation plan revealed that the percentage of roads with poor ride quality more than doubled from 2002 to 2011 for principal arterials (2 percent to 4.8 percent) and rose 350 percent on nonprincipal arterials (2.4 percent to 8.6 percent); the state’s freeways ranked 44th out of 50 states (50th being the worst).

Road budgets also don’t go as far as they used to because costs have been high and continue to rise. “Everything a road department does—from paving roads to crushing gravel—is driven by [high] petroleum prices,” said Blattie, from MACo.

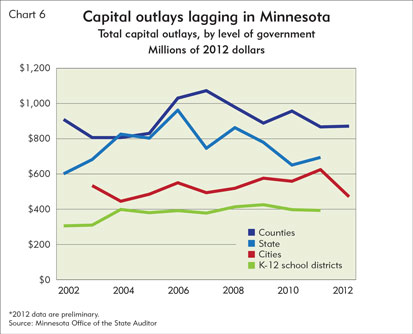

Roads also represent only part of a state’s investment in infrastructure; other types of capital investment include drinking water and treatment systems, schools and other facilities. Since the mid-2000s, total capital outlays have been flat to negative at Minnesota’s many levels of government. In Minnesota, real capital spending by the state government and counties has seen a sharp drop in recent years; school district spending has been flat for close to a decade, and cities saw a small and steady increase through 2011, but a sharp decrease last year (see Chart 6).

Public opinion? Yes and no

Governments walk a tightrope between balanced budgets, greater efficiency and quality public services.

“It’s a challenge to innovate and invest in this current climate,” said Linnea Mirsch, deputy county administrator with St. Louis County in northern Minnesota. “Doing more with less has now become doing less with less.” The county has cut staff and services or, in some cases, not added staff despite increased service demands, all of which lead to longer wait times for existing services. For example, health and human services has seen a significant increase in demand “due to the effects of the economy on the people we serve,” yet the county has not added staffing, said Mirsch.

The recession and slow recovery have forced cities to adapt to a new normal. Some are likely much better at it than others. “The art of budgeting is to ask for what you want and take what you need,” said Alec Hansen, executive director of the Montana League of Cities and Towns. He described municipalities there as “stable,” which included modestly rising wages, while those of state workers have been frozen. “Generally, I think [Montana] cities are in pretty good shape. We could use more money, but we’re getting by.”

Some of that stability likely rests on a hardscrabble notion of being satisfied with what you have. “In small towns across the prairie, service levels might be lower, but they’re adequate,” said Hansen. “We get by with less. … [Tight budgets] are a condition of survival. It doesn’t mean you can’t do it.”

Montana cities have had a lot of practice, according to Hansen, going back to a 1986 law that froze property tax rates. “If you live under a property tax freeze for 26 years, you learn pretty quick what’s needed.” When budgets get tight, Hansen said the first to go are things like spending for parks and recreation that don’t represent a “middle-of-the-night crisis with sirens.”

Whether tight budgets are seriously eroding the quantity and quality of public services is ultimately a question for taxpayers, whose current attitude appears to run the gamut, according to district sources. Many said constituents have been patient and understanding because they know money is tight. Others said they’ve seen the ugly side of constituents who want services and believe local governments could offer them if only they weren’t so wasteful.

In either case, tight budgets might be encouraging a better understanding of what local government is and does, and what services taxpayers are willing to pay for. Spartz, from the Minnesota counties group, said most people “don’t deal with the county except when writing this big check twice a year” for property taxes, while counties’ core services are for courts and social service programs like welfare and medical assistance. “Most of those are services people don’t want to get entangled with.”

Blattie, from MACo, said that property taxes often disconnect the service from its cost for many taxpayers. “They think that 100 percent of their property taxes go for roads, another 100 percent goes to schools and another 100 percent goes for [other local services],” said Blattie. “[People] fail to value public services until something happens that you make a personal connection with. You don’t need the fire department until you needRon Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.