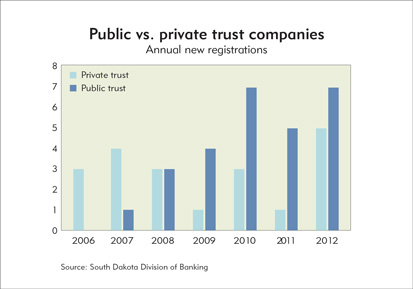

Strong privacy rights for trusts and trust companies make it difficult to deduce much from the robust growth in these firms in South Dakota. But one notable trend surfaces from their mere registry with the state: In recent years, there has been a notable increase in public trust firms.

Trust companies come in two basic forms: public and private. In a nutshell, private trust companies are family-based and have been the core of trust business until fairly recently. They are limited to a single family lineage, but often include multiple generations. A private trust company does not act for unrelated families or accept outside business. In general, these companies are not required to provide as much regulatory capital as public companies and do not have to establish the same in-state presence so long as the trust company allows state trust regulators to conduct efficient examinations.

The circumstances surrounding the creation of a private trust are many, and they are often unique to the family. In terms of the wealth required—well, as the saying goes, if you have to ask how much money you need, you don’t have enough.

“The general rule of thumb I have heard several times is that a family needs $200 [million] to $250 million in assets to make a [private] trust company worthwhile from a cost perspective,” said Bret Afdahl, director of the South Dakota Division of Banking. “Having said that, we do have families with less assets that chose to establish their own [private] trust company for other reasons,” many of which are specific to South Dakota’s regulatory environment for trusts (see main article).

A public trust company, in contrast, resembles a traditional bank trust department in some ways; it solicits and accepts new accounts from unrelated families or individuals who typically have much less wealth. Think of it as the retail trust business.

Public trust charters have increased dramatically since 2007 (see chart) and now represent 60 percent of all trust companies in South Dakota. But rather than replacing private trusts (which have continued growing), public trust companies appear to be carving an entirely new niche.

Many of these public trust companies are serving people interested in self-directed independent retirement accounts, according to Afdahl. These financial vehicles allow an individual to make his or her own investment choices for a retirement plan. However, the Internal Revenue Service requires that a qualified trustee or custodian hold the IRA assets on behalf of the IRA owner.

Enter public trust companies, many of which are playing administrative and custodial roles for individual trusts and do not invest or otherwise manage trust assets. “We have had a lot of interest from groups interested in doing [this] work,” Afdahl said.

He added that self-directed IRAs also allow individuals to invest in nontraditional assets such as real estate, precious metals, business ownership and other assets that cannot be held in traditional retirement accounts and have become more common since the financial crash in 2008.

This custodial role distinguishes independent, public trust companies from many bank trust departments, which typically manage assets and offer a full slate of other services. “They [banks] want to manage assets. They don’t want nonmoney assets,” according to Pierce McDowell, co-CEO of South Dakota Trust Co., a public trust company in Sioux Falls that provides administrative trust services. The firm administers more than $9 billion in assets, but it does not invest or otherwise manage those assets. “In our world, I don’t see a lot of banks competing with us.”

And it might be hard to imagine, but Afdahl said—and the South Dakota market is showing—that new public trust companies are serving a previously neglected class of customers a cut below the uber-wealthy.

“We consistently hear from applicant groups that the larger institutions do not provide the same level of customer service to people in certain net worth categories,” said Afdahl. Big trust companies and banks “want the ultra-high-net-worth customers, but do not show as much interest in or provide the same level of customer service to those below the very upper crust. This has provided an opportunity for smaller companies” to pursue clients in different markets nationwide from their headquarters in South Dakota.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.