Note*

Original and updated versions of the calculator available

Our approach to analyzing potential costs of additional bank regulation has three advantages. First, it is a quantification; it provides a dollar figure. We believe quantification of regulatory costs augments more anecdotal reviews. Second, the quantification is simple and transparent. This allows interested parties to evaluate the weight and credibility they wish to assign to the dollar estimates. Finally, the approach is flexible. Banks may respond to regulation by increasing training, by shifting staff to activity that generates less revenue or by doing nothing differently. In all cases, the bank’s response will manifest itself in lower profits, as if the bank altered its head count. We also allow interested parties to customize key model inputs to tailor the simulation via a spread sheet attachment.

In sum, our goal is to advance quantification of additional regulatory costs rather than arguing for a specific cost estimate.

We illustrate the approach in three ways. We provide the following:

- Cost estimates under a baseline scenario with a fixed set of key assumptions.

- Cost estimates in which we vary the key assumptions from the baseline scenario.

- An “Electronic Additional Bank Regulatory Cost Calculator” allowing users to specify all key variables in their calculation.

By way of example, we find that the median reduction in profitability for banks with less than $50 million in assets is 14 basis points if they have to increase staff by one half of a person; the reduction is 45 basis points if they increase staffing by two employees. The former increase in staff leads an additional 6 percent of banks this size to become unprofitable, while the latter increase leads an additional 33 percent to become unprofitable.

Our Approach to Quantifying the Cost of Additional Regulation

We model the effect of incremental regulatory costs by assuming that community banks will need to hire additional staff. We examine this effect on banks that have been in existence for five or more years and have assets less than $1 billion, slightly more than 5,400 banks as of year-end 2012.

We group banks into asset-based cohorts. We require only two additional inputs:

- the number of staff each bank will hire and

- the compensation of these staff.

We then reduce the reported net income from year-end 2012 for each firm by the estimated increase in total compensation costs. Finally, we measure the corresponding changes in the distribution of return on assets (ROA) within each size cohort.

In order to preserve the simplicity of our approach, we do not model the impact of higher compensation expenses on bank income taxes. We simply apply the additional expenses as “below-the-line” adjustments to reported net income. This process overstates the effect on bank profitability by not taking into account the reduction in income taxes that would occur.1

This approach to quantification has three main advantages. First, it captures the “bottom line” from a wide range of regulatory cost effects. Regulatory costs may not manifest themselves as the hiring of more staff. Such costs could present themselves as less revenue, since staff may spend more time on nonrevenue-generating activity. Alternatively, training expenses for staff may increase. Regardless, our approach to quantification captures the full range of increased costs or lower revenue, as both result in lower earnings. Second, the approach is transparent and simple. These traits allow users to determine the significance to give to the estimates when considering the quantification. Finally, the simulation framework is flexible and allows alternative assumptions to be easily tested. We can specify different asset size ranges for the cohorts, vary the number of additional employees needed and the related compensation expenses, and alter the time period examined. We use that flexibility to perform alternative quantifications and to offer an automated platform to carry out similar analysis.

Our approach has a number of limitations. Our approach does not

- measure any of the “psychological” costs of increased regulatory activity;

- account for dynamic changes in the risk-taking of banks (e.g., the bank takes on more risk in response to higher fixed costs);

- recognize the potential that new regulation could increase firm profitability by, for example, increasing confidence in the banking system.

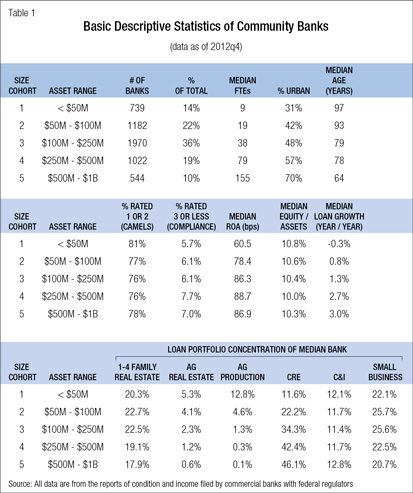

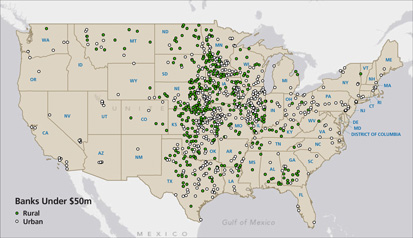

Table 1 provides descriptive characteristics based on year-end 2012 Call Report data for our sample of banks broken down by asset size cohorts. The smaller institutions tend to be older, somewhat more highly rated and more rural, and to have higher agriculture-related loan concentrations. The smallest community banks—those with assets less than $50 million—also have noticeably lower profitability levels. See Appendix 1 for the geographic location of these small banks.

Cost Estimates with Varying Levels for the Key Inputs—The Generic Case

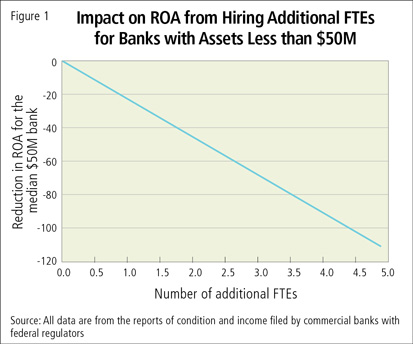

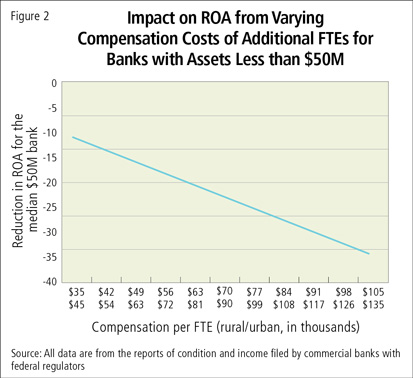

As noted, we have two key inputs, the number of additional staff banks hire and the compensation of these staff. We begin by illustrating the impact of different levels for these inputs on the profitability of the smallest banks in our sample (those with assets less than $50 million). Figure 1 shows the median change in ROA for these banks at varying levels of incremental hires. Figure 2 depicts the change in ROA for the same group of small banks, but instead varies the compensation costs while holding constant the number of full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) at one. This approach generates the following results:

- Hiring of one FTE reduces ROA by approximately 23 basis points for the median bank with assets below $50 million. For this stylized example, we assume that the compensation costs for each additional FTE are $70K for rural banks and $90K for urban banks.2 Each additional FTE reduces the median bank’s ROA by the same amount. For example, if a bank in this size category needed to hire four FTEs, the change in ROA would be roughly 90 basis points (see Figure 1).

- Assuming compensation of $42K and $54K for staff in rural and urban markets leads to a reduction in ROA of 13 basis points for the median bank with assets below $50 million if it were required to hire one FTE. Each additional $7K in compensation costs reduces the median bank’s ROA by approximately 2.25 basis points. For example, if a rural bank needed to pay $91K in compensation costs for the incremental FTE, the change in ROA would be nearly 30 basis points (see Figure 2).

Measuring the Materiality of the Profitability Reductions—A Representative Scenario

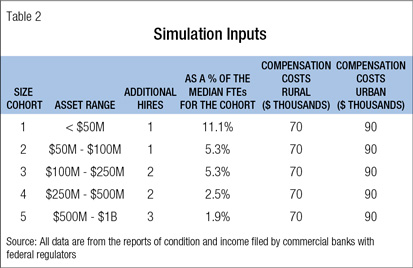

We extend the analysis from the previous section. We do so by measuring the materiality of the profitability decline faced by community banks arising, in concept, from additional regulation. To do so, we utilize a representative scenario in which we impose a proportionally higher regulatory cost burden on smaller banks. That is, a smaller bank has a relatively higher cost of regulation compared to a larger bank. This approach is consistent with research that suggests fixed-cost and economies-of-scale components to regulatory compliance.3 In this scenario, we also report the new hypothetical hires due to additional regulation as a percentage of the number of FTEs at the median firm within each banking size cohort. Specifically, the number of assumed new hires for banks with assets less than $50 million is 10 percent of the number of employees for those banks. The other size cohorts hire proportionally fewer employees.

Table 2 reports the simulation inputs for each asset size cohort used in the scenario. As in the previous section, we use $70K and $90K as the compensation costs for rural and urban banks, respectively. We chose the exact number of additional employees we add for each cohort in this representative scenario solely for illustrative purposes. That said, the relative numbers appear roughly consistent with one limited set of empirical data that shows higher proportional costs for smaller firms (see Appendix 2 for additional details on banks’ relative hiring due to regulatory compliance).

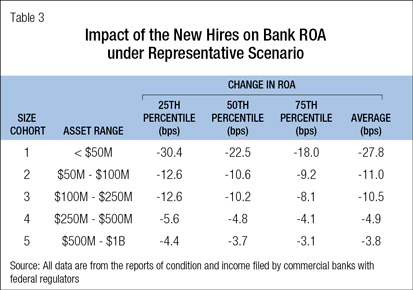

Table 3 reports the distributions of ROA reductions for each size cohort resulting under the representative scenario. As designed, the impact on profitability is most significant for the smallest institutions. The median bank with assets below $50 million would experience a drop in ROA of nearly 23 basis points, while the median firms in the larger size cohorts would encounter a decline of 11 basis points or less.

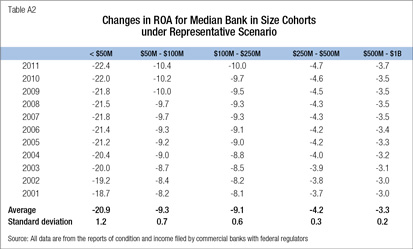

We review the additional staff costs on profitability since 2001 to determine if our results are time specific (profitability is particularly low in the current period).4 The median changes are quite stable across all five size cohorts during this period. Appendix 3 reports historical results for this section using year-end data over the period 2001-11 (see Table A2 for information regarding the change in ROA for the median firm over this period).5

We measure the materiality of the change in profitability for the representative scenario in three ways. First, we simply count the number of firms that shift from being profitable to unprofitable as a result of the additional compensation expense. Second, we set a “minimum required ROA” based on de novo bank experience and count the number of firms that would fall below this value as a result of the regulatory change.6 Lastly, we examine how the changes in profitability in the scenario would alter the chances of bank failure and downgrade as calculated by Federal Reserve models.

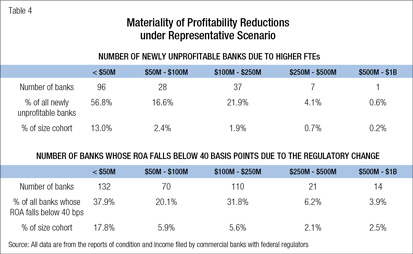

Table 4 reports both the number of newly unprofitable banks and the number that fall below our “minimum required ROA” as a result of the higher compensation costs in 2012.

Nearly 60 percent of the total number of banks that would become unprofitable due to the regulatory change are in the smallest cohort using data from 2012. Moreover, 13 percent of the banks with assets less than $50 million would become unprofitable, compared with roughly 2 percent or less of the other size groups. Similar results are found with respect to the number of firms whose profitability falls below the “minimum required ROA” of 40 basis points. The smallest asset size group accounts for a plurality of the banks that end up falling below the minimum ROA level. Banks in this size category are between three and eight times as likely as the other size groups to end up below the ROA cutoff. These results are consistent with the historical experience (see Appendix 3 for additional historical data on these measures. Appendix 3 also provides graphs with the percentage of banks that breach materiality standards across different levels of the key assumptions).

Finally, we determine how the simulated changes in profitability would impact the likelihood of future weakening in the supervisory ratings of banks (i.e., “rating downgrades”) and the chance of failure. Bank supervisors rate all banks on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the weakest and 1 being the strongest; a bank with a weaker (higher) rating on this scale receives more supervisory attention and resources relative to a bank with a stronger (lower) rating.7

The Federal Reserve has developed empirical models—collectively called SR-SABR—to forecast the likelihood that a bank will have a supervisory rating downgrade or will fail. The downgrade forecast comes from an adverse rating change model, while the failure prediction comes from the so-called viability model. The adverse change model estimates the likelihood that a bank will experience a downgrade of the CAMELS composite rating (if the bank were examined in the next quarter). The viability model estimates the likelihood that a bank will fail or become critically undercapitalized within the next two years. 8

We use the SR-SABR models to estimate the effect of lower ROA on the likelihood of a ratings downgrade or failure at a bank. The adverse change model relies on many variables to make its forecast. One of the variables is ROA. To determine the effect of the cost of regulation on the forecasted chance of downgrade, we substitute the ROA that results from our baseline simulation for the actual earnings observations for all banks. We then calculate the difference between the original probability of receiving a downgrade and the estimates with the lower ROA (for the SR-SABR model estimated as of year-end 2011). Only 2 percent of the firms in the four largest size cohorts experience an increase of 1 percentage point or more in the probability of receiving a downgrade. The impact from the earnings reduction on the smallest banks is slightly larger—12 percent of these firms experience an increase of 1 percentage point or more in the likelihood of an adverse rating change, and 2 percent would see an increase of nearly 5 percentage points due to the earnings reduction.

We also examine the change in the forecasts from the SR-SABR viability model resulting from substituting the lower earnings for banks projected by our baseline regulatory cost reduction for banks’ actual earnings. These changes are immaterial for most community banks. Indeed, 99.5 percent of all community banks with assets above $50 million would see their failure probability increase by less than a single percentage point. However, the impact is noticeably higher for banks with assets under $50 million. Over half of these firms would experience an increase of at least 1 percentage point in their failure probability, and more than 30 percent would see their failure probabilities rise by more than 5 percentage points.

Finally, to provide additional data on the potential effect of regulatory costs on the smallest banks, we report descriptive characteristics for the smallest banks whose ROA falls below either 0 or 40 basis points as a result of the regulatory change relative to banks that do not breach these standards. In short, the two populations are quite similar. Additional details are reported in Appendix 4.

Measuring the Materiality of the Profitability Reductions—An Alternative Cost Structure Scenario

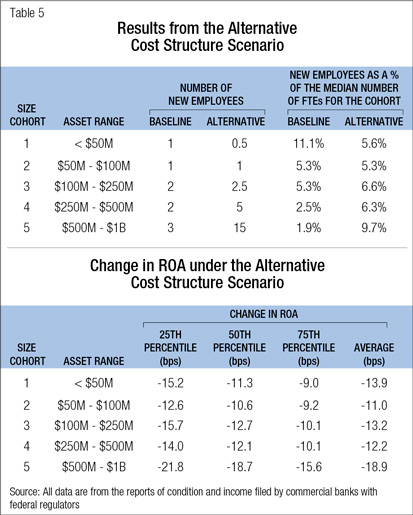

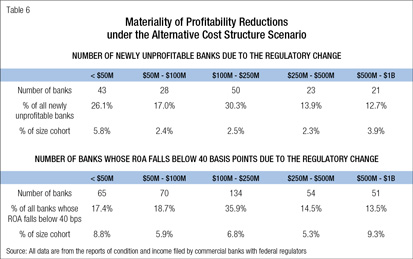

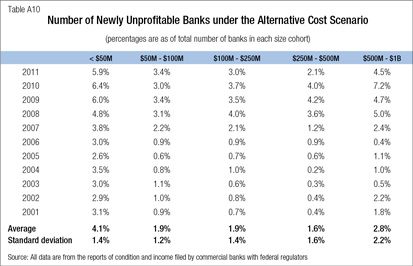

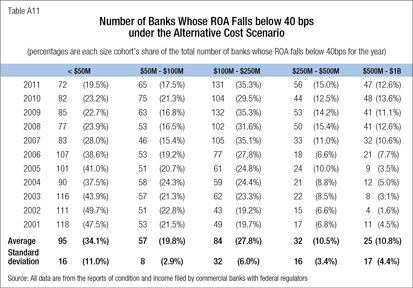

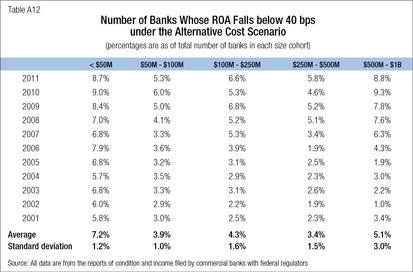

In addition to the scenario described above, we also tested an alternative cost structure in which larger firms hire a disproportionately higher number of employees than smaller firms. Table 5 reports the staffing levels that were used as inputs in the alternative cost structure (compensation costs were kept at the same values as in the baseline scenario) along with the percentiles of the distribution of changes in ROA. As expected, the disproportionately higher employee levels for larger firms result in them incurring the largest reductions in ROA. Table 6 reports data on the materiality of the profitability reductions in a format analogous to Table 4. Importantly, we find that the smallest size cohort still comprises a significant share of both the newly unprofitable firms and the firms whose ROA falls below 40 basis points. Indeed, banks with assets below $50 million are still one of the most likely groups to breach the two profitability thresholds. Additional historical data for the alternative cost structure are available in Appendix 5.

Note

* The views expressed in the paper of those of the authors. The authors thank Dean Amel, Kevin Bertsch, Betsy Duke, Jeff Gunther, Sarah Bloom Raskin, Ken Spong, Todd Vermilyea and members of the Federal Reserve’s Community Banking Research Group for their comments.

Endnotes

1 The data provided in this paper do not account for the S-corporation elections, which result in banks paying lower income taxes and having higher reported net income amounts. We did analyze whether accounting for S-corporation status had a material effect on our results by using a proxy for the net income earned by S- corporations (generated from the Uniform Bank Performance Report (UBPR)). Using this S-corporation measure leads to only a very small change in profitability of 2 basis points or less compared to our original estimates in the representative scenario. Additional details are available upon request.

2 Our selection of $70K and $90K for the rural and urban compensation costs is based on data reported by community banks in 2011 for the “salaries and employee benefits” item and the number of FTEs data in the Call Report. We use the 90th percentile of the distribution of salary and benefits per FTE because we expect regulatory professionals to be relatively “expensive.” This part of the distribution ranges from $70K to $76K for rural community banks and $82K to $99K for urban community banks across the cohorts.

3 Prior research has documented that regulatory costs exhibit economies of scale (thereby posing a larger burden on smaller institutions). See Staff Study 171 from the Board of Governors for a detailed review of the research.

4 We adjust the compensation costs by the CPI over time to control for inflation effects.

5 Results for different percentiles (25th and 75th, for example) of the distributions are also stable over time.

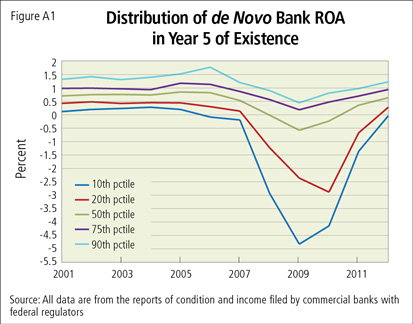

6 Specifically, we review the ROA of de novo banks in their fifth year of existence. Prior research suggests that de novo banks past this period perform similarly to established firms. Based on historical data (see Figure A1 in Appendix 3), we infer that investors expect at least a 40 basis point ROA; this level of ROA captures what investors have received from most de novo banks in their fifth year of existence for much of the past decade. This proxy for a materiality standard is clearly ad hoc and is meant to help illuminate the magnitude of the reduction in ROA rather than representing a definitive “bright line.”

7 The Federal Reserve’s Commercial Bank Exam Manual discusses bank ratings in great detail.

8 SR 06-2 describes the SR-SABR model and its use in the supervisory process.

Appendix 1

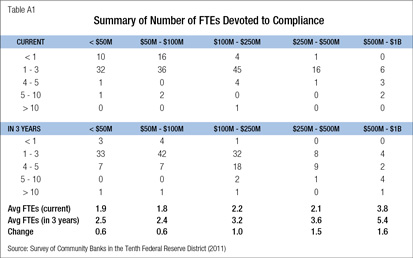

Appendix 2: Additional Information on Community Bank Hiring of FTEs in Response to Increased Regulation

The key input parameters for our baseline analysis are estimates of the number of incremental employees that would need to be hired to perform the additional regulatory compliance work and the related salary and benefit costs. As described in the main text, we utilize 2011 Call Report data to determine the compensation costs of the new employees in rural and urban areas. We feel that our choices for the number of employees that would need to be hired, while designed to be illustrative, are also consistent with the very limited empirical data available on this topic.

In particular, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City surveyed community depository institutions in its area in August 2011 and asked them to report the number of FTEs that are currently devoted to regulatory compliance and the number they expect to employ for this function in three years. Table A1 summarizes the results from the survey.

A similar survey of community banks in the New York and New England areas was conducted by Northeast Capital and Associates. Seventy percent of the banks that responded to the survey indicated that they believed compliance costs would rise by at least $50,000 annually over the next few years. Lastly, in testimony offered to the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit, the chairman of the Community Bankers Council of the American Bankers Association (and CEO of a $1.4 billion bank in Maryland) reported that his organization had hired one additional full-time employee to deal with changes in existing and future regulations and that the total cost of this regulatory compliance work would be $275,000.

Appendix 3: Extending the Representative Scenario

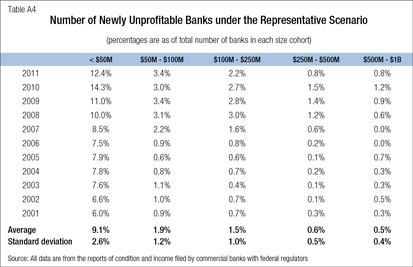

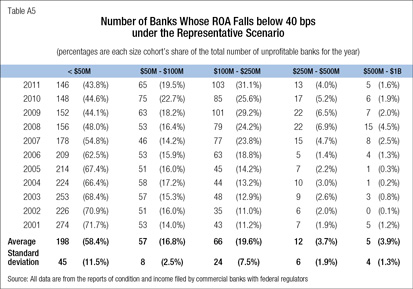

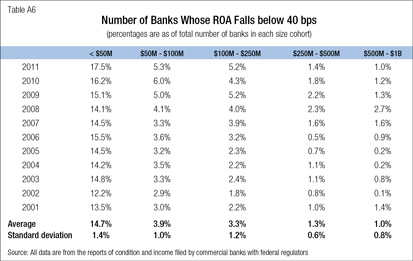

This appendix reports (a) historical results for the analysis performed in the main body of the paper for the representative scenario and (b) extensions of the materiality analysis performed in the body of the paper.

Table A2 reports the change in ROA for the median firm in each size cohort over the 2001-11 period using the simulation parameters from the representative scenario.

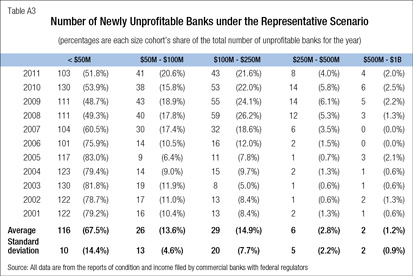

Tables A3 through A6 report the materiality of the profitability reductions that would have occurred during the 2001-11 period using the simulation parameters from the representative scenario. Tables A3 and A4 refer to the number of banks that become newly unprofitable as a result of the regulatory change, and Tables A5 and A6 present data on banks whose ROA falls below 40 basis points in response to the new regulations. As noted in the text, the compensation costs are adjusted by the CPI to control for inflation effects.

Figure A1 graphs key percentiles from the distribution of de novo bank profitability measured in year 5 of their existence from 2001 to 2012. With the exception of the financial crisis, the distribution is largely stable over time.

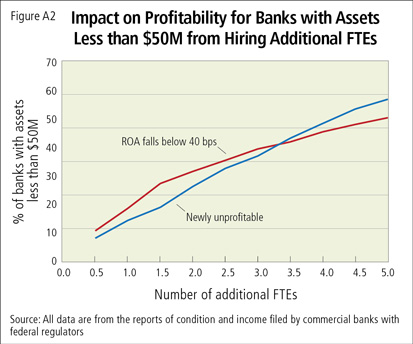

Figure A2 extends the profitability analysis discussed in the main body by showing the impact on profitability of hiring different numbers of FTEs for banks with assets less than $50 million (the other simulation inputs for the representative scenario are kept constant).

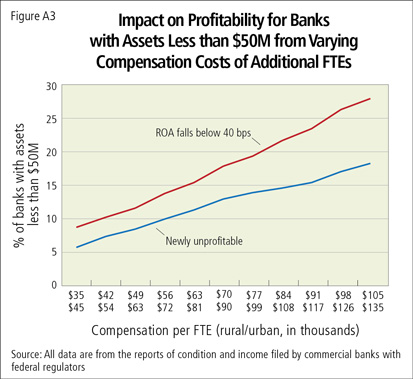

In a similar manner, Figure A3 also extends the profitability analysis, showing the impact on profitability of different compensation costs for banks with assets less than $50 million (again, the other simulation inputs for the representative scenario are kept constant for this illustration).

Appendix 4: Descriptive Characteristics of Banks with Assets Below $50 million

In this appendix, we report on the characteristics of banks with assets below $50 million that fall below a materiality standard and those that do not. In general, the two populations are quite similar. Both groups have similar capital ratios, largely comparable loan portfolio concentrations and relatively equivalent composite ratings and asset quality measures.

Appendix 5: Historical Results from the Alternative Cost Structure Scenario

This appendix reports historical results for the analysis performed in the main body of the paper for the alternative cost structure scenario.

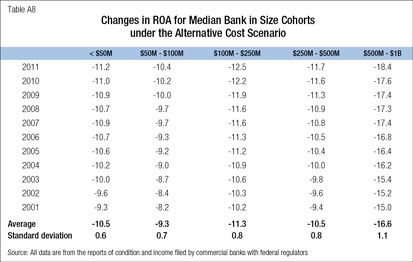

Table A8 reports the change in ROA for the median firm in each size cohort over the 2001-11 period using the simulation parameters from the alternative cost structure.

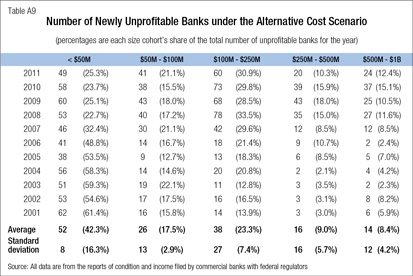

Tables A9 through A12 report the materiality of the profitability reductions that would have occurred during the 2001-11 period using the simulation parameters from the alternative cost structure. Tables A9 and A10 refer to the number of banks that become newly unprofitable as a result of the regulatory change, and Tables A11 and A12 present data on banks whose ROA falls below 40 basis points in response to the new regulations. As noted in the text, the compensation costs are adjusted by the CPI to control for inflation effects.