What would you do if you won a million-dollar lottery?

You might address some long-needed home improvements. You might buy a vehicle (hmm, his and hers?) and maybe lend a helping hand to family and friends because they know you’ve got the dough. It’s probably not enough to retire on, so you’ll have to keep bringing in a regular paycheck. But it’s sure nice to have some financial breathing room.

The big question: How much will you save knowing—in your heart of hearts—that saving a healthy portion of that windfall is in your long-term interest? If you’re like most, your intentions will be good, but your actions will fall short.

For state governments, striking oil is a bit like winning the lottery. It can mean untold millions, even billions, in new tax revenue. But the jackpot is not big enough or permanent enough for lawmakers to put on the revenue cruise control and relax, which creates a fiscal policy dilemma for energy-producing states.

Like real-life lottery winners, states use oil and gas tax revenue differently. Many use it for short-term purposes, enhancing general fund expenditures that would otherwise require public service cuts or higher taxes elsewhere in the economy. Some might have enough left over to pad their funds for a budgetary rainy day.

But when it comes to permanent, legacy-type savings, there’s often little or nothing to save. “It’s very difficult to put money aside in a political environment. And once there is, it’s hard to keep it there,” said Mark Haggerty, an economist with Headwaters Economics, of Bozeman, Mont., who has studied oil tax policy among the states.

North Dakota has decided to buck that trend—to be the lottery winner that saves more than others. Two years ago, the state took the unusual step among U.S. states of setting up a permanent trust fund—called the Legacy Fund—complete with a constitutional requirement that 30 percent of oil and gas severance taxes get socked away for the future. At fiscal year end this summer, the Legacy Fund had assets of about $1.2 billion, which puts it among the larger energy trusts in the country. The state also has another permanent trust fund, the Common Schools Trust, established more than a century ago and fairly low-profile until the oil boom lit a fire under it. Now it has twice the assets of the Legacy Fund.

No single approach to the harvest of oil and gas and its resulting tax revenue is necessarily the wisest. All things equal, a prudent approach toward the harvest of finite natural resources would likely include socking away something, maybe even a lot, for future generations. But all things are not equal among states, given their different natural resource bases, populations, demographics, public service demands and even political considerations that ultimately influence whether tax revenue is spent or saved.

North Dakota’s approach to oil and gas revenue and its fiscal positioning for the future compares with few other states, including many that have reaped substantially larger oil and gas revenue over past decades. North Dakota’s permanent trusts, particularly the Legacy Fund, are poised for robust growth thanks to ballooning contributions from rising energy taxes coupled with a mandate for long-term savings.

Outside the United States, North Dakota’s trust fund approach also compares favorably with that of its neighbor government in Alberta, Canada. While it’s not in the same asset class as Norway’s renowned oil and gas trust fund—the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world—the Legacy Fund nonetheless has similarities that bode well for building a sizable nest egg while North Dakota’s energy boom plays out.

Empty oil cans

Natural resource endowments are widely viewed as public assets, benefiting both current and future generations. For natural amenities like lakes, public benefit comes from their immediate use, but also from their preservation so that others might enjoy them years from now. For assets like timber and minerals, public benefit can also come through their sale, with tax proceeds used to fund public services. For nonrenewable resources like oil and gas, the thinking goes, a portion of revenue should be saved to benefit future residents. Enter the trust fund, which converts a hard asset in the ground into a long-term financial asset.

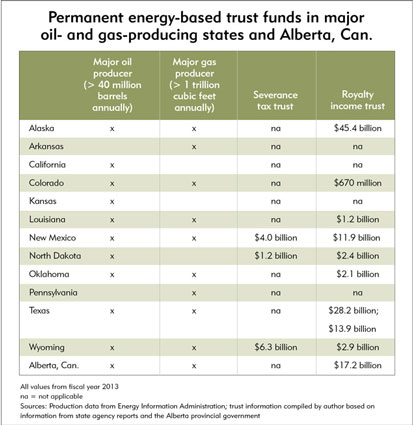

Permanent oil and gas trust funds are typically funded by one of two sources: One is a severance tax, which is levied when a resource is extracted (or severed) from the land. The other is royalties, which are paid to landowners (public and private) in exchange for the right to harvest resources from public and private land. Royalty income tends to be more modest than severance taxes because most energy production occurs on private rather than public lands. (The exception is Alaska. More on this later.)

A review of states with major energy production found only a handful of permanent trust funds (see table). North Dakota is one of a few with two sizable trusts, one funded by severance taxes and one by royalties. A number of states have no notable energy trust fund to speak of despite a legacy of energy production. California has produced more than 9 billion barrels of oil since 1981 (third most among states) and more than 13 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (ninth most), yet has no trust fund because it levies no severance tax on energy production, and last year earned just $2 million in royalties from production on state lands.

Most states, however, take in significant revenue from energy production. The majority of it comes in the form of severance taxes—something on the order of $20 billion in 2012 alone. However, only three states dedicate significant amounts of severance tax to permanent trusts: New Mexico, North Dakota and Wyoming. The largest of these trusts is the Wyoming Permanent Mineral Trust Fund, with assets of more than $6 billion.

(Some fine print: Colorado devotes some severance tax to a perpetual trust whose assets are comparatively small and dedicated to revolving loans for water and other environmental projects. Alaska saves none of its severance tax—about $6 billion in 2012—but dedicates at least 25 percent of royalty and related income to a permanent, general-use fund.)

Two years ago, North Dakota established its own permanent trust, dubbed the Legacy Fund, and attached to it a constitutional mandate that it receive 30 percent of extraction and production taxes paid on oil and gas production. The fund topped $1 billion in April—after just 20 months—and is adding more than $80 million a month.

The Legacy Fund was created in part by a problem every state wishes it had: too much money. To understand, go back about a half dozen years. Oil and gas tax revenue was ramping up quickly and “no one had their hands around” what to do with the money, said Pam Sharp, director of the state Office of Management and Budget.

By 2008, political leaders and the public began talking more about the need to save some of this revenue for North Dakotans. In 2009, the state put to referendum a proposal to set aside 50 percent of all oil and tax revenue, but the measure was defeated by voters. “They thought it was too much [tax revenue] to set aside,” said Sharp.

During this time, the state had a quasi-permanent trust fund—though mostly in name only. Called the Permanent Oil Tax Trust Fund, it amassed more than $1 billion dollars and was set up as a long-term savings fund. But it had no spending restrictions, “so every year it got raided for special interest spending,” said John Phillips, president of the North Dakota Economic Development Association (NDED).

A second statewide referendum took place in 2011 to set aside a smaller percentage (30 percent) of oil and gas severance taxes, which won by a wide margin because voters believed “if they didn’t set it aside, the Legislature would spend it,” said Sharp. The measure also put assets under lock and key, preventing lawmakers from spending anything until 2017, and only then with a two-thirds majority in both legislative chambers.

There is an element of serendipity to North Dakota’s current fiscal state. The oil boom there is comparatively large in scale given the state’s population. The state is also less dependent than other states on oil and gas taxes to fund ongoing government expenditures. But so too are there mounting challenges and costs at the local level related to oil and gas development (discussed at length in the July 2013 fedgazette).

“Given the challenges, I think we’ve done a pretty good job,” said Sharp. “It’s been really difficult to know [how to plan] when we’re still not at the top of [oil revenue].”

John Walstad is a lawyer and code revisor with the North Dakota Legislative Council, involved in the drafting of laws related to oil and gas taxes. He said there was “significant legislative will to put a trust fund in place,” and supporters of the fund “have a pretty typical North Dakota view ... that you don’t spend your last dime for immediate gratification. You set aside something in good times so you can ride out the hard times. ... North Dakotans have never understood how you can spend money you don’t have.”

Now in place and growing rapidly, the Legacy Fund appears to be widely supported in the state; nary a local or state source contacted by the fedgazette opposed or criticized the fund aside from minor concerns about the relative percentage of the set-aside or curiosity about the fund’s long-term objective, which has not yet been decided by lawmakers. In an informal fedgazette online poll with 55 responses from across the state, nearly four of five supported the Legacy Fund. However, two-thirds said they did not want the state to raise the percentage of tax revenue dedicated to the trust.

Ron Ness, president of the North Dakota Petroleum Association, said, “We were major supporters of the Legacy Fund. It’s the right thing to do for future generations and to ensure the wells keep producing forever. I have been a major supporter and believe it’s important for my three young children’s future in North Dakota.”

It doesn’t hurt that the fund is piling up savings. The state projects the fund will reach $3 billion by the end of fiscal year 2015—and that might be conservative; the fund reached $1 billion this spring far faster than earlier estimates. As of May, the state had also started seeking a better yield on the fund’s assets, which had been invested in conservative fixed-income instruments returning less than 2 percent annually.

Sizable and automatic tax contributions, combined with higher investment returns, should help the Legacy Fund catch up to the nation’s other two severance tax state trusts, both of which had a big head start but are receiving significantly smaller tax contributions than the Legacy Fund. Wyoming’s Permanent Mineral Trust Fund was created in 1976 and receives about 40 percent of all oil, gas and coal severance tax revenue—about $350 million in fiscal year 2012 on severance taxes of almost $900 million. The fund is also required to distribute 5 percent of its five-year rolling market value to the state general fund—good for $215 million in 2012.

New Mexico’s Severance Tax Permanent Fund was also started in 1976 and has $4 billion in assets. The state takes in more than $400 million in severance taxes, but much of it goes to pay off a state-based revolving loan fund used by local governments for bond financing. After meeting bond payment obligations, the remaining severance revenue is distributed to the permanent fund. In turn, the fund is required to distribute 4.7 percent of its assets to the general fund—$176 million in 2012. As a result, the fund’s net growth comes from investment returns.

Royalties: Your oil highness

More states capitalize permanent trusts through royalties and related income like lease-bonus payments (see table). Most of these trust funds have been around since the mid to late 1800s, when the federal government granted millions of acres to 30 states, including every Ninth District state, with the express purpose of leveraging these lands and their natural endowments for the benefit of public education. Currently, only 20 state-based school trusts are still in existence from these land grants, according to Margaret Bird, director of Utah’s School Children’s Trust.

Again, North Dakota’s Common Schools Trust fares well by comparison. It was established in 1889 when the federal government gifted several million acres of land to the state. Fortunately for North Dakota, about one-third of the state’s remaining endowment of 2.5 million acres holds oil and gas deposits, which generated $350 million in royalties and other income for the school trust during the first 21 months of the 2011-13 biennium, according to figures from the state Department of Trust Lands.

But the state also has in place a formula that, depending on total receipts and allocations elsewhere, funnels some of the surging severance tax receipts to the Common Schools Trust. In the 2011-13 biennium, $192 million in severance tax revenue was allocated to the Common Schools Fund, according to state budget figures.

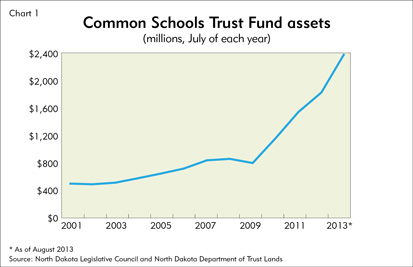

Combined with investment returns, these major contributions have had a powerful financial effect. It took the Common Schools Trust more than 100 years to reach $1 billion in assets, but just two years to earn the second billion (see Chart 1). The state expects the fund to reach almost $4 billion by the end of fiscal year 2015.

The trust allocates money to the state’s K-12 school districts based on the average value of financial assets, and the fund’s growth has filtered down in a big way. This year, school districts will receive $66 million from the fund, double the level from 2011.

Despite the steep ascent of assets in both of North Dakota’s permanent trusts, a small handful of trusts in other states dwarf them both. Most of these trusts receive royalties from energy production on state lands. The state of Texas has two of the country’s largest resource-based trusts, with combined assets of $42 billion. Each fund receives considerable oil and gas royalties as well as other income from public lands, totaling an estimated $1.2 billion in the most recent fiscal year, according to the state’s biennial revenue estimate in January. Investment earnings from the funds support public K-12 and state higher education institutions, to the combined tune of $1.6 billion last year.

“Texas is pretty good at squirreling away money,” said Paul Ballard, CEO and chief investment officer of the Texas Treasury Safekeeping Trust Company, which manages the two trust funds. The two trusts also have grown big through simple longevity, having been created in 1876, with a statewide oil boom only a few decades away at the turn of the century.

But if there is a trust celebrity in the room—at least among U.S. states—it’s Alaska, whose Permanent Fund currently stands at about $45 billion, funded from royalties and related income from production on state lands. Unlike other trusts funded by royalties, Alaska’s is not dedicated to the benefit of public education, in part because the state did not take part in the federal land grant program, given its late arrival as a state. That allows the fund to issue a direct payment annually (officially called a dividend) to every state resident. Those checks have fluctuated of late, spiking as high as $2,000 per person in 2008 but declining last year to $878. Since the fund’s inception in 1976, the state has returned $20 billion to residents.

Low expectations?

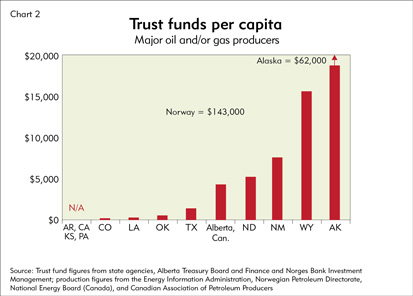

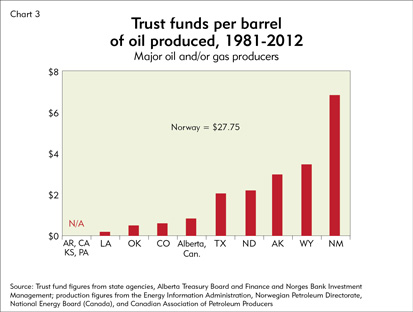

By mere asset size, Alaska and Texas are the cream of the U.S. crop of trust funds. But other metrics suggest that these and other producer states have little to show, given their respective legacies of energy production.

For example, since 1981, Louisiana has produced 4 billion barrels of oil (fourth most in the country) and 113 trillion cubic feet of gas (second only to Texas). Over this period, the state has taken in $33 billion in tax revenue, according to data from the state Department of Natural Resources. Its lone trust fund, the Louisiana Education Quality Trust Fund, has only $1.2 billion in assets.

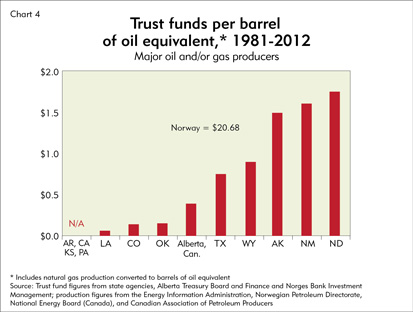

The Lone Star State might have $42 billion in trust funds, but it’s also the elephant of U.S. oil production. Its current production leads second place North Dakota by a factor of three; since 1981 it has been the largest producer of both oil and gas by a wide margin, and that ignores significant earlier production not tracked by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Against that backdrop, the state’s trust funds look a little less robust when measured on a population or energy production basis, falling to middle of the pack among major producing states (see Charts 2-4; the province of Alberta and Norway are also included in the trust analysis and discussed later in this article).

On a population basis, Alaska appears to be the fat cat of state energy trusts, with trust fund savings of about $62,000 per resident. But on a production basis, its savings rate looks much more modest. While Alaska stuffs as much as one-third of royalties and related income into its trust fund (good for about $900 million in 2012), the state also earned $6.2 billion that fiscal year in additional severance and other taxes. All of it went to the state’s general fund.

Alaska’s heavy use of energy revenue for general fund expenditures rather than future savings is not necessarily “bad” per se; as a legislated matter, lawmakers (and the voters who empower them) have preferred immediate public services to future ones. Neither is the state’s habit of paying dividends to state residents from its trust fund necessarily imprudent. Such a judgment depends on a comparison of the private use of these dividends with the likely alternative if funds were left in the trust. Both matters are outside the scope of this article.

But the trust’s celebrity status may be in jeopardy. Alaska currently gets up to 90 percent of its general fund from volatile oil and gas revenue. But production has been falling for decades, with government revenue propped up by high oil prices and the highest severance tax rates in the country. The trust fund is nowhere near the size necessary to replace annual oil and gas revenue should production continue to drop, as expected, or if oil prices fall significantly. Dividends to residents typically exceed annual royalty contributions, so the fund already depends on investment returns for growth.

Then this spring, the state Legislature overturned its existing tax structure, changing its severance tax rate and stripping out the tax progressivity (based on oil prices) that pushed per-barrel tax rates to almost 43 percent in 2012. The new rate—a flat 35 percent, with a $5 per barrel tax credit—is still exceptionally high compared with other states, but various incentives and exemptions are expected to cut effective tax rates to half that level in some cases. Estimates suggest the state will bring in $1 billion to $2 billion less in tax revenue—a big impact on a state budget with few other revenue sources.

The tax change is meant to encourage producers to explore and drill for more oil. “We’re in a place where declining oil production isn’t going away” unless new production is found elsewhere, said Nils Andreassen, executive director of Institute of the North, an Alaska think tank. Though the industry and state believe there is considerable oil yet to be found—offshore, in the North Slope and in unconventional shale oil—none has yet been uncorked. “These are long-term bets because they don’t know what else to do,” Andreassen said.

The state is now spending more than $7 billion annually, while a sustainable revenue stream given production trends is more along the lines of $5.5 billion, according to a January report from the University of Alaska-Anchorage.

“The state will have to face up to fiscal realities,” said Andreassen. “The dividend is a time bomb. ...Given the [fiscal] situation 10 to 20 years out, it will have to stop” if the state has any hope of building a nest egg that can replace current oil and gas tax revenue in perpetuity.

Oil trust exports

In this context, North Dakota is faring well among oil- and gas-producing states; it has the highest savings rate among U.S. states in terms of total, oil-equivalent production since 1981. Also favoring the state is the fact that those savings are likely to grow considerably if production and oil prices remain strong as expected.

To the north, the province of Alberta produces the large majority of Canadian oil, which helped create and capitalize the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund, currently holding $17 billion in assets. The provincial government holds about 80 percent of mineral rights, and the province produces about 2.3 million barrels of oil a day—about three-and-a-half times North Dakota’s output. Much of it is bitumen, a heavy, sour crude from tar sands whose production has been increasing steadily. The government assesses no severance tax, but applies sliding-scale royalties of up to 40 percent, which brought in about $11.6 billion in fiscal year 2012, according to provincial statistics. However, none goes to the trust fund.

The Heritage trust’s circumstances have changed drastically since its founding in 1976. After seven years of steady contributions, the fund hit $11.4 billion. But subsequent contributions started to fade and went away entirely in 1988. The government also started appropriating the fund’s investment earnings for general and capital expenditures; since the early 1980s, the fund has seen $33 billion in investment earnings transferred to the provincial general budget.

Heritage assets have grown modestly since then, but in real terms the fund’s value is about 30 percent lower than three decades earlier—despite the fact that Alberta oil production has been rising steadily for more than 10 years. So despite having one of the larger energy trust funds in North America, Alberta’s rank on a production basis is much poorer (see Charts 2-4).

Alberta lawmakers had a change of heart this spring, announcing a new fiscal framework that legislates more savings “and sets Alberta on the path towards less reliance” on oil and gas taxes, according to a press release. Among other things, the fund will retain all investment income starting in 2016. Assuming normal market returns, this “responsible savings strategy, the first in over 25 years” is projected to push the Heritage Fund’s asset values to more than $24 billion in just three years, according to the fund’s latest annual report.

Norway, and everybody else

Any serious policy talk about permanent oil trusts, especially outside the Middle East, eventually leads to one country: Norway, the rainmaker of oil trusts. Although its model differs fundamentally from that of any U.S. state, Norway nonetheless exemplifies the adage of saving early and often.

Major oil deposits were discovered in the continental shelf of the Norwegian Sea in the late 1960s, shortly after the national government had claimed sovereignty over it. Oil production started in the 1970s, with the country determined to develop the resource at a pace that would not overwhelm the national economy while generating public funds in perpetuity.

Over the next two decades, the means of production evolved from initial investment by foreign producers to the creation of the state-owned company Statoil in the 1970s to the formation of a separate organization (State’s Direct Financial Interest, or SDFI) in the mid-1980s to issue production licenses to private producers. Licensing created the incentive for investment that followed.

Rather than holding auctions for licenses, or collecting royalties on production, the SDFI claimed a minority ownership stake in every subsequent development project as a condition of issuing a production license. This made the government an early-stage investment partner with private firms active on the shelf—currently about 50, according to an annual report by the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate—sharing both the risk in every drilling pad erected and the reward for every barrel produced.

This arrangement also required the government to develop the technical and human resources to successfully manage its partnership investments and gave the country an incentive to streamline the time-consuming process of permitting and development. All of these factors have lowered the investment risk for private firms, said an official with the Norwegian embassy in Washington D.C., who asked not to be named.

At the same time, the country hasn’t forsaken its regulatory and environmental responsibilities. Norway has never allowed the flaring of natural gas (commonplace in North Dakota) despite the fact that all-offshore production makes its collection and marketing an expensive proposition. The country was also one of the first to levy a carbon tax (in 1992) on domestic oil and gas production; the tax was raised again last year, almost doubling to $70 per ton of CO2.

Finally, the Norwegian government takes one of the largest energy tax bites of any country, at 78 percent of net earnings (after factoring in production costs).

This tiered-revenue strategy has paid off handsomely for Norway. The country collected $60 billion in revenue in 2011 (the most recent year available)—$36 billion in taxes, $21 billion from its ownership stakes via SDFI and $3 billion in dividends as a minority owner in Statoil, which the state spun off in 2001.

But here is the major Norwegian twist: None of this money flows directly to the national government. Rather, it goes to the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), the country’s permanent oil trust, created in 1990. With assets of $722 billion as of July, it is the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, benefiting a country with just 5 million people (the population of Minnesota) that currently produces less oil per day than Texas.

The national government receives annual revenue from the fund equal to 4 percent of (smoothed) assets, no more and no less, so lawmakers aren’t tempted to politicize the assets and subsequent spending from the pension fund. This revenue, projected to be about $21 billion this year, makes up more than one-quarter of the national government’s budget.

By funneling huge revenue to the GPFG, the country has what U.S. states and most other oil-producing countries only talk about creating: A trust fund with enough wealth to reliably sustain government revenue once the oil has run out. Though production has declined rather precipitously of late, from 3.4 million barrels a day in 2001 to about 1.9 million in 2012, the country nonetheless believes it has sufficient reserves for at least two or three more decades of oil and gas production. With annual distributions only a small fraction of assets, investment returns should be able to protect the fund’s assets over time with a little to spare even without a contributing energy sector.

The way forward

Domestic sources widely view the Norway model as politically unrealistic for U.S. states.

“There is a clear benefit for states and communities from sharing” current revenue with future generations,” said Haggerty, from Headwaters Economics. “But I don’t think states are willing to entertain that [Norway] model. ...I don’t see a path to that. We’re going the opposite direction.”

In most states, Haggerty noted, “there are very different cultural and political circumstances” compared with Norway. For starters, Norway owns all oil-producing lands, and oil is considered a public resource. “In the U.S., the private sector is believed to be the best source to extract” that resource.

But he added that North Dakota shares some traits with Norway, like a small and homogeneous population, a predilection to save and even some unique political-economy ways of doing things differently, such as state ownership of the Bank of North Dakota, a unique arrangement in the U.S. “North Dakota is different from Texas and a lot of places,” Haggerty said.

The state has put in place the mechanisms necessary to save substantial amounts of oil and gas revenue for the benefit of future generations. What the state will do with its Legacy Fund over the long term is mostly guesswork. Lawmakers cannot begin to tap its assets until at least 2017, and then only with two-thirds majority approval in both chambers. Sources suggested a wide variety of possibilities, from establishing a college scholarship fund to directing a steady stream of revenue to the general fund. Sharp, from the OMB, said some residents favor an Alaska-style fund that is allowed to grow big enough to generate annual stipends for state residents. “We get that a lot—‘be like Alaska so everyone gets a check.’ It’s popular with some.”

But most sources said there hasn’t been much thought given to how to spend the trust money because of the urgency of dealing with the immediate effects of the oil boom. “I don’t hear a lot of people talking about it. It doesn’t go beyond, ‘Hey, look, there’s a billion dollars in the Legacy Fund,” said Phillips, the head of NDED. “People are really focused on what’s happening now” in oil patch communities.

Walstad, from the state’s Legislative Council, agreed. With access to funds still several years away, “there has not been much action, but [some] stirrings have developed about what to do when 2017 comes around.”

Keith Lund, vice president of the Grand Forks Region Economic Development Corporation, sees “real opportunity” in the Legacy Fund. “I like to think we’ll invest that” in something significant and strategic, whether it be long-term general funding, or support for higher education, he said.

Lund said some fear that there could be a statewide initiative in 2017 to send the savings back to taxpayers, “where everyone gets a check for $20,000. Who’s going to vote against that? Seems like a good idea at the time, but you later wish you hadn’t done that,” Lund said. “I’d like a check, but I hope we don’t do that. But we haven’t had those conversations yet.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.