While unemployment rates continue to fall, if slowly, employers in many states are still grappling with higher tax rates for unemployment insurance (UI), which fund unemployment benefits in each state. Recent data from the U.S. Department of Labor suggest a mixed bag of improvements this year among Ninth District states.

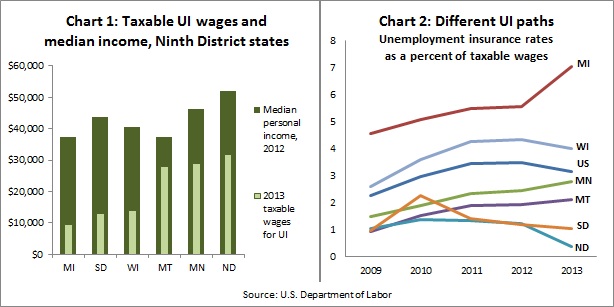

Employers pay UI taxes for every covered worker on payroll, but every state does things a little differently. For example, the amount of income subject to UI taxes varies widely among states. In Michigan, employers pay UI taxes only on the first $9,500 of wages paid. In Wisconsin, it’s $14,000, and in North Dakota, almost $32,000 (see Chart 1). As a result, UI tax rates tend to be inversely related to how much income is subject to UI taxes, with Michigan’s rate the highest and North Dakota’s the lowest (see Chart 2). Higher UI rates tend to reflect benefit generosity as well.

But the direction of UI rates are heavily influenced by each state’s economy, and the Great Recession gave UI systems in most states a one-two punch: It put many out of work, thus greatly increasing unemployment benefit spending; it also lowered overall employment, which lowered the amount of UI taxes coming into UI trust funds (which pay unemployment benefits). As a result, UI tax rates on covered employees had to go up for most UI systems to maintain adequate cash flow during the recession and subsequent recovery.

The greatest increases in UI tax rates came between 2009 and 2011, once the full effects of the recession had settled in and states had exhausted their UI trust funds. Since then, average UI tax rates have moderated; half of district states saw a slight decline in 2013 as a percentage of taxable wages, and the other half increased, with Michigan seeing a significant rise (see Chart 2).

In the Dakotas, strong economies and high job growth, coupled with low unemployment and modest jobless benefits, have pushed UI tax rates to exceedingly low levels (see Chart 2). Wisconsin’s rate has also started to bend lower. But rates for Minnesota, Montana and especially Michigan have continued to increase. (Technically, only the northwestern portion of Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan are in the Ninth District, but the whole of both states are included in this analysis.)

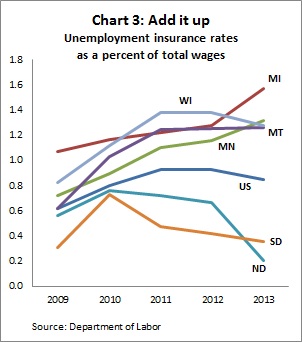

In some ways, the ultimate cost of UI taxes to state businesses is easier to see as a percentage of total wages. Here, the rank among district states still generally holds, but the Dakotas set themselves off even further for the low cost of their UI programs, while other district states bunch more tightly together (see Chart 3).

There are other good-news stories outside of the Dakotas. While Minnesota’s UI rates have continued to increase in 2013, the state has managed to wipe out a $770 million loan from the U.S. Treasury that it needed to keep paying unemployment benefits a few years ago. Wisconsin has done that one better: UI rates inched down this year, and though the state UI trust fund still has a $300 million loan with the federal government, that’s down from $1.4 billion just two years ago.

(Update: On Tuesday, November 19, the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development announced that UI rates will drop in 2014, thanks to growth of the state UI trust fund to $1.2 billion. It's estimated the move will save state businesses almost $350 million in UI taxes.)

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.