It’s human nature: When people get nervous about the future—fearing unemployment, diminished wealth or some other economic setback—they tend to increase saving as an insurance policy. But expectations of hard times can become self-fulfilling; precautionary saving reduces demand for goods and services, cutting output and putting people out of work. In turn, job losses and foundering businesses spur more desired saving. A vicious recessionary cycle takes hold.

Jonathan Heathcote

A large body of economic research has examined the role of this mechanism in deep and protracted downturns, including the Great Recession and the Great Depression of the 1930s. (See, for example, “Engineering a Paradox of Thrift Recession,” SR 478, and “‘Paradox’ Redux,” June 2013 Region.) But such crises of confidence are not inevitable; they require certain conditions to occur, according to recent research at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Fabrizio Perri

In “Wealth and Volatility” (Minneapolis Fed SR 508) Minneapolis Fed Monetary Advisers Jonathan Heathcote and Fabrizio Perri argue that lower asset values make the U.S. economy more vulnerable to confidence-driven downturns.

“What’s novel about this paper is that a drop in the level of household wealth makes the possibility of a self-fulfilling crisis more likely,” Perri said in an interview.

To test their theory, the economists develop a model economy in which the level of wealth influences saving behavior and aggregate demand. Heathcote and Perri complement that with an analysis of data on consumption by rich and poor households during the Great Recession. Their findings have implications for public policy, suggesting that generous unemployment benefits can sustain consumer demand in the face of uncertainty by reducing the impulse to save.

Wealth and “animal spirits”

Over the past decade, U.S. households saw large and persistent declines in their net worth. Starting in 2007, households headed by individuals in their prime working years experienced a large (50 percent) and persistent drop in their median net worth. This drop marked the start of the worst economic retreat since the Great Depression.

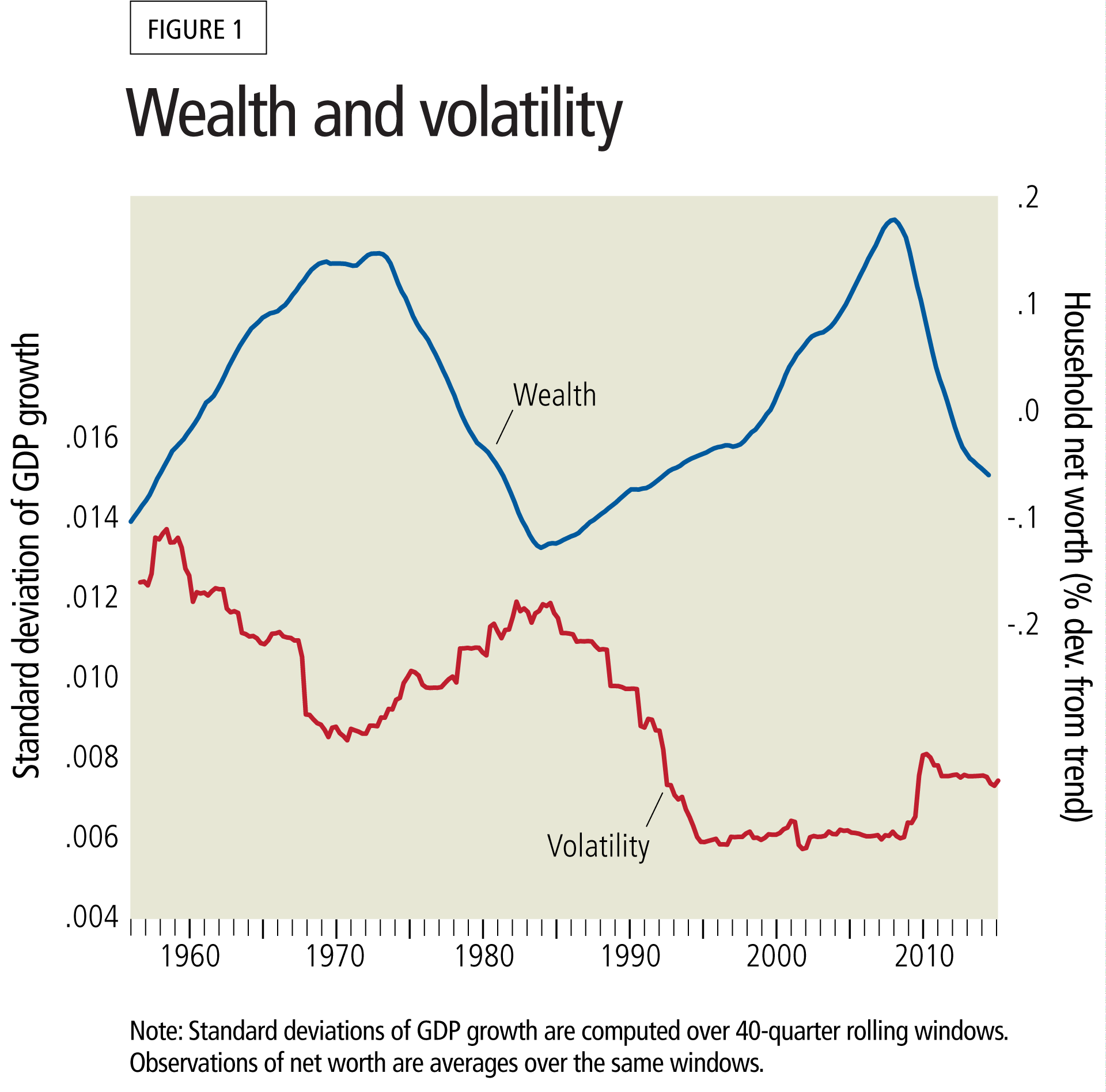

This wasn’t the first time that a loss of wealth had coincided with a recession or period of economic frailty; macroeconomic data for the past 60 years (see Figure 1) show that when household wealth drops, aggregate output often becomes volatile, making the economy susceptible to weakness. Conversely, when net worth is high, output tends to be more stable and the economy more resistant to negative shocks.

Previous research on the link between asset values and output volatility has emphasized the impact of output volatility on asset prices. But what if causality runs in the other direction, with fluctuations in asset values affecting variances in output—and in consumption and employment? In Heathcote and Perri’s model, changes in consumer confidence—what British economist John Maynard Keynes termed “animal spirits”—can drive economic fluctuations. Crucially, according to this hypothesis, asset values determine the amplitude of these confidence-driven fluctuations—whether economic activity stays on a fairly predictable path or becomes more volatile, increasing the likelihood of a severe downturn. “Wealth here is the prerequisite, the thing that tells you whether the economy is fragile or not,” Perri said.

In the model, individual members of households decide how much to spend and save as the unemployment rate and other economic conditions change over time. The model is relatively simple, according to Heathcote and Perri, lacking features that make dynamic market models harder to solve. But it captures human motivations that are key to the economists’ analysis.

Higher expected unemployment encourages people to save, because money put aside can smooth consumption in case of job loss. And how much they save depends upon household wealth, specifically housing prices in the model. When housing prices are high, people worried about their jobs save proportionately less—and therefore consume more—because wealth can be shared within the household, helping to support unemployed members. In this way, high wealth prevents a confidence-driven collapse in demand and output.

On the other hand, when housing prices fall, people are more disposed to save, and saving increases markedly with the expected unemployment rate. “Thus, a recession driven by a self-fulfilling wave of pessimism becomes possible,” Heathcote and Perri write. “If agents collectively expect higher unemployment, they all simultaneously reduce demand, leading to a fall in hiring and rationalizing the expected unemployment.”

Simulations from the model can generate patterns for housing prices and unemployment very similar to those seen in the United States over the course of the Great Recession. Housing prices decline well before the unemployment rate begins to rise. The economy contracts quickly, with plummeting asset prices and rapidly rising joblessness. And recovery is sluggish; in both the model and the real economy, housing prices remain depressed five years after the recession officially ended in 2009. The authors don’t try to explain the initial drop in house values; they assume a decline in consumer preference for housing.

The output of the model also fits the pattern of the Great Depression, in which a sharp decline in wealth after the stock market crash of 1929 was quickly followed by massive unemployment that lasted for years.

Heathcote and Perri’s theory predicts that confidence-driven recessions are necessarily persistent—once started, the cycle of self-fulfilling low expectations is hard to break—and that recessions with steep drops in output are likely to be especially long-lasting. Their theory also predicts that the lower are asset values, the more volatile the economy becomes—and the greater the likelihood of a severe recession.

Rx for confidence

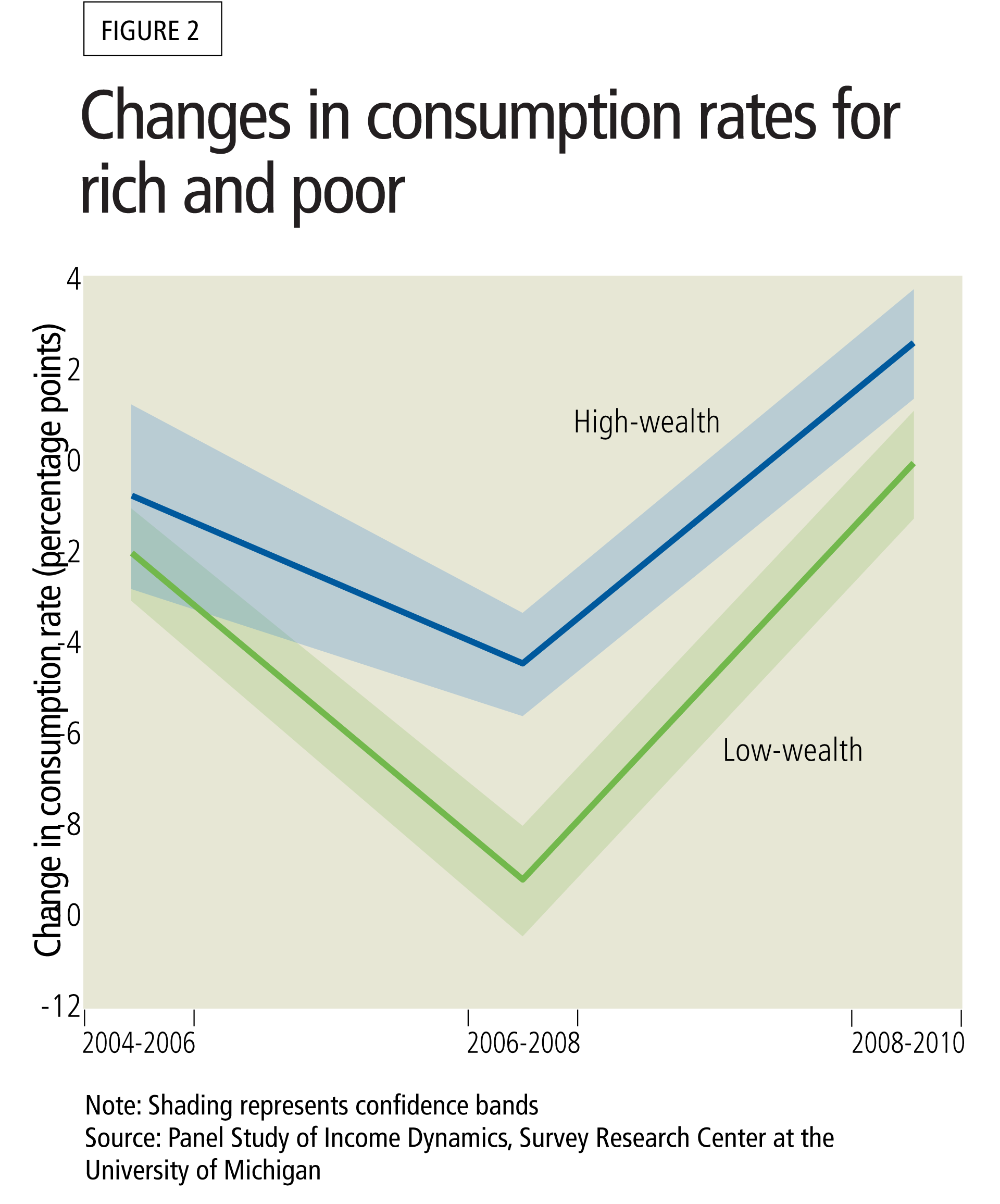

If household wealth determines the degree of precautionary saving in response to unemployment risk, low-wealth households should, theoretically, cut their consumption (in proportion to their income) more than high-wealth households during a recession. Breaking new empirical ground, Heathcote and Perri analyze two types of U.S. data on household income, wealth and expenditures to reveal just such a disparity during the Great Recession.

Their key finding is that at the onset of the recession, the expenditure rate of low-wealth households declined significantly more than that of high-wealth households (see Figure 2). Both rich and poor households reined in spending, but the poor reduced expenditures about 4 percent more relative to the rich, suggesting that precautionary saving increases as wealth falls.

Heathcote and Perri’s investigation highlights the central role of household wealth in setting the stage for confidence-driven recessions and perpetuating them. It also informs policy choices for combating severe recessions. The economists compare two governmental responses to recession: increasing government spending and extending unemployment benefits. Both aim to revive the economy by stimulating aggregate demand.

The reasoning behind government purchases financed by taxing workers seems sound: Aggregate demand should rise because public spending isn’t constrained by the precautionary saving motive. But in the model, raising taxes on workers reduces personal wealth, encouraging household saving and canceling out the economic lift from higher government spending.

Taxing workers to provide generous unemployment benefits also diminishes household wealth. But this type of government intervention is more effective in combating recession than broad government spending because it directly targets precautionary saving; a buffer against the pain of unemployment induces people to save less. “If the problem is that households aren’t spending enough because they’re worried about future unemployment risk, this policy is a good one because, by removing the cause of their worries, it encourages increased spending,” Perri said.