The first time Skip Duchesneau got a phone call from the owner of the Prairie Rose Apartments, in 2008, he declined the man’s offer to sell him the 16-unit complex in Red Lake Falls, Minn. Duchesneau, the president of property development and management firm D.W. Jones, Inc., had visited the property before and concluded that improving its poor physical condition was more than he wanted to take on: the roof needed repairing, the soffits and fascia were worn, even the light switches and electrical plug plates needed replacing.

“We would have had to gut it,” he says. “Everything except the sheetrock would have needed to be changed out.”

The following year, when the owner again called and offered to sell him the property, Duchesneau’s answer hadn’t changed. But in 2010, when he received a similar pitch from an employee at the Greater Minnesota Housing Fund (GMHF), a nonprofit organization focused on affordable housing in rural Minnesota, he reconsidered.

The employee highlighted a few aspects about this potential acquisition that made it more palatable: the prospect that Duchesneau could receive federal tax credits; the possibility that, with enough physical upgrading, the development could maintain the rental support that it had been receiving from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); and the ability to re-amortize the property’s existing United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) mortgage under favorable terms. While Duchesneau recognized that all those options would add complexity to the purchase, he wasn’t unaccustomed to projects that required layers of financing to fall into place; after all, in partnership with his wife Lori, who is president of sister company D.W. Jones Management, Inc., he already owned and operated 30 multifamily developments (and managed 90 more) in northern Minnesota, and some of those projects had come together with complicated financing. In the end, Duchesneau decided that the development merited his company’s involvement and moved forward with a purchase agreement. In 2012, after securing the appropriate financing package, he reopened the fully rehabbed Prairie Rose—new roof, light switches, and all.

For Stephanie Vergin, the employee at GMHF who made the phone call to Duchesneau, the sale was a great outcome. She participates in a collaborative effort organized by the Greater Minnesota Interagency Stabilization Group (ISG), which monitors some of the roughly 110,000 units of subsidized affordable housing in Minnesota1 and, if there’s a risk that the units will lose their subsidies and convert to market rate, pursues opportunities to keep the units affordable. A fellow Greater Minnesota ISG member who works at HUD had informed her that, due to multiple health and safety inspection failures, the Prairie Rose development was at risk of losing support from HUD’s Section 8 rental assistance program, which provides housing subsidies so low-income tenants can cover the cost of market-based rents. Without the collaborative efforts of Vergin (who now works for the USDA) and the other members of the Greater Minnesota ISG, the development would have likely lost its Section 8 support and the state’s inventory of affordable units would have decreased by 16.

According to Robyn Bipes, chair of the Greater Minnesota ISG and director of programs and lending at GMHF, the Prairie Rose is just one of a growing number of properties that are at risk of dropping off Minnesota’s affordable housing rolls. Some of them will definitely convert to market rate, but not all—not if she and her Greater Minnesota ISG colleagues can help it.

“We’re talking about many, many hundreds of affordable housing units that may be lost,” she says, “but we are trying to do what we can to save as many as possible.”

A matter of maturing mortgages

A significant source of affordable rural housing in Minnesota is the state’s large inventory of rental dwellings funded through USDA Rural Development (USDA RD) Section 515, a program that supports affordable multifamily rental housing in rural areas. As of 2015, of the roughly 46,000 subsidized affordable housing units in rural Minnesota2 , approximately 10,600, or 23 percent, are financed with a Section 515 mortgage.

The Section 515 program, which was established with the passage of the Federal Housing Act of 1949, provides an interest credit that reduces the cost of the mortgage payments on the development, which thus reduces the rents a property owner needs to charge to pay back his or her loan. The USDA RD Section 521 program was established to work in conjunction with Section 515 and provides direct rental assistance to tenants residing in some of the units within a property. The rental assistance (which is distinct from HUD’s Section 8 program) allows owners to charge tenants the equivalent of 30 percent of their adjusted annual income, and the program pays the property owner the difference between that amount and the USDA RD-approved rents for the property. As soon as a Section 515 mortgage matures and the property’s owner makes the final loan payment, however, the rental subsidy is cancelled and the owner may elect to increase the rent charged. Of the 10,600 Section 515 units in Minnesota, about 6,700 receive rental assistance; approximately 750 of those units (including 432 with rental assistance) are in properties that are set to mature by the end of 2018.

Under Section 515, the USDA is authorized to make direct mortgage loans to parties interested in building affordable multifamily rental housing for low-income families, elderly persons, and persons with disabilities.3 A general geographic condition of the loan is that the developments must be located outside of major metropolitan areas—specifically, in rural areas and towns with 20,000 or fewer people or on federally recognized tribal lands. The loans available through the program can be made for up to 30 years at an effective 1 percent interest rate, amortized over 50 years, and have a balloon payment due at the end of the loan term.

Nationally, the first loan made through the program was for the construction of a 26-unit rental development in Grove City, Minn., in 1964. Since then, the Section 515 program has financed approximately 14,000 properties throughout the country, for a total of more than 550,000 affordable rental units, of which 421,000 currently remain in the program. Of these, approximately 62 percent receive rental assistance.4

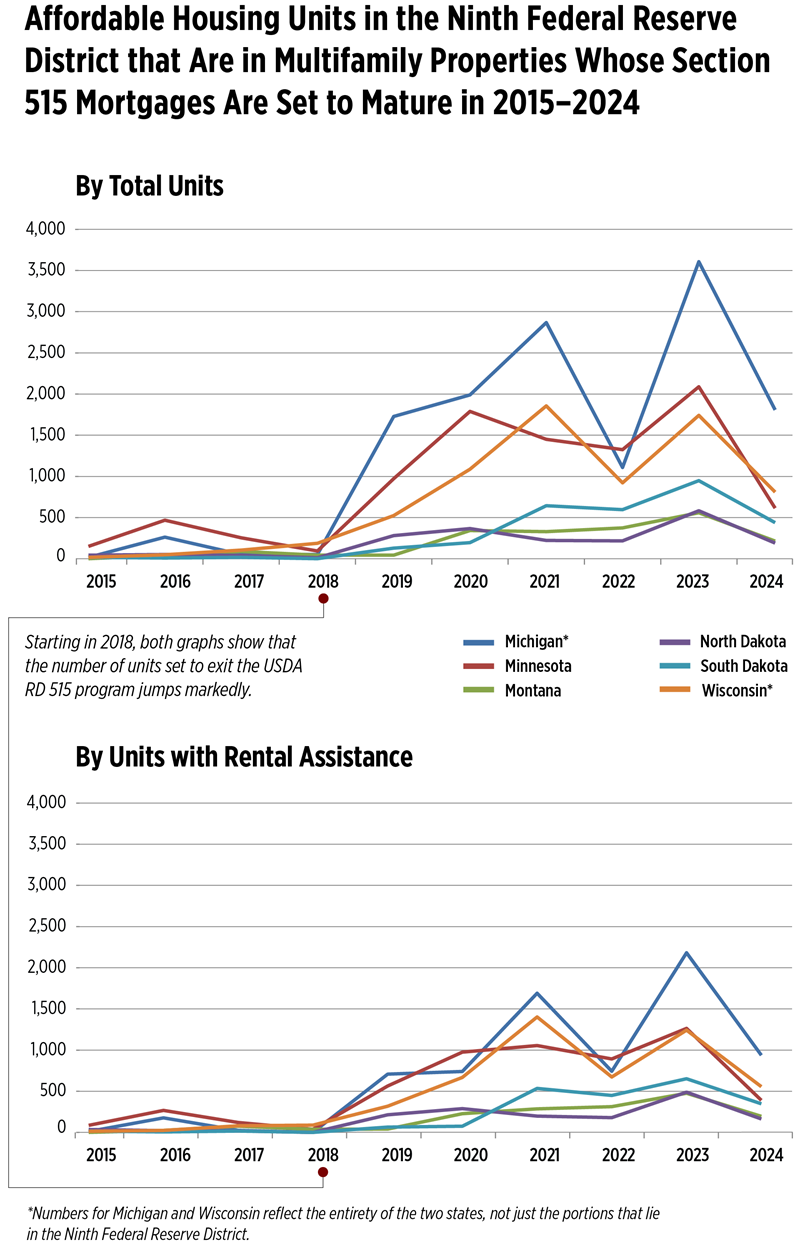

According to Bryan Hooper, the deputy administrator for Multifamily Housing in the USDA’s Rural Housing Service, the Section 515 mortgages on roughly 80 percent of this national housing portfolio (or about 11,500 of 14,000 properties) will mature over the next ten years, which will have direct consequences for the low-income tenants who reside in the mortgaged properties. (See the accompanying graphs for a breakdown of maturing 515 mortgages in the Ninth Federal Reserve District.)

“This is a key issue because the residents will lose the rental assistance that is currently provided to them,” says Hooper, noting that, on average, the adjusted income of the tenants in subsidized units is about $12,000 a year. “They will face significant rent increases, and they are not people who can afford an extra $200 or $300 a month.”

Collaboration among colleagues

The Greater Minnesota ISG is made up of personnel from government and nonprofit affordable housing entities, including GMHF, USDA RD, HUD, the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development, Federal Home Loan Bank of Des Moines, Duluth LISC, Minnesota Housing, and the Minnesota Chapter of the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials. The idea of creating an interagency group took root in 1993, when funders of affordable housing in the state recognized a need to work proactively on preservation efforts because, among other reasons, Minnesota’s subsidized housing stock was beginning to show age. The group originally focused on housing in the Twin Cities area; a spinoff group—the Greater Minnesota ISG—was created in 1998 to focus on other communities throughout the state. The Greater Minnesota ISG meets every other month to discuss the inventory of government-subsidized rural affordable housing in Minnesota and identify properties that are collectively perceived to be important to preserve or stabilize.

“We then strategize about what can be done about them,” explains Bipes, noting that the Greater Minnesota ISG, as an entity, does not fund housing projects. “What resources could be tapped? What programs could we look to? What is the best course of action to help keep these units affordable and available?”

Greater Minnesota ISG members learn about specific properties in need of stabilization or preservation in one of two ways: from an owner or from a funder. For example, an owner might approach a funder, such as the USDA, and explain that his or her Section 515-funded property is in need of renovation. On the other hand, a funder can inform his or her Greater Minnesota ISG colleagues of a housing complex that receives Section 8 assistance from HUD but has failed a number of annual health and safety inspections and is therefore in jeopardy of losing its federal subsidy. That was the case when the Greater Minnesota ISG member from HUD notified Vergin about Prairie Rose.

In both cases, says Bipes, if Greater Minnesota ISG members agree that the projects are good candidates for preserving or stabilizing—for instance, if they are in a strong market with relatively high rents but receive rental assistance to help offset the amount a low-income tenant must pay—they will advise the current owner or a new buyer regarding the best way to apply for funding. The owner or buyer then takes it from there.

“In some respects it’s like we’re playing matchmaker, telling owners about possible funding opportunities or actually finding a new owner for a property whose current owner wants to sell,” she says. “Ultimately, it’s up to the owners or potential buyers to decide if the programs and financing opportunities we’ve referred them to are strong enough to move forward on.”

Rick Goodemann, chief executive officer of affordable housing developer Southwest Minnesota Housing Partnership (SWMHP), says that his organization is frequently approached about acquiring a property—sometimes by the Greater Minnesota ISG but often by owners who want to sell their affordable housing development. When SWMHP ultimately decides to move forward with a purchase, it meets with a member of the Greater Minnesota ISG to figure out how to proceed in securing the appropriate financing package.

“We consult with the ISG to help us figure out the best way to move forward,” he says.

The way forward often leads to Minnesota’s annual funding cycle for affordable multifamily housing, wherein housing developers might submit applications to multiple funders. In 1994, several members of the Greater Minnesota ISG agreed to create a common request for proposals for developers to respond to when applying for tax credits and other forms of funding. Called the “Consolidated RFP,” the shared application guidelines not only save owners and developers from having to fill out multiple, different proposals for each of the funding agencies but also force the funders themselves to coordinate their own funding objectives and synchronize their priorities.

“And then after receiving the proposals, those agencies evaluate to decide how to fund the different projects that meet their strategic priorities,” explains Anne Heitlinger, housing program and policy specialist for Minnesota Housing and member of the Greater Minnesota ISG. “It’s a really coordinated process where people from the different agencies make sure they’re funding projects in a way that maximizes the dollars spent.”

Minnesota-specific policies

In order to further preservation of small properties in rural areas, Minnesota Housing created the Rural Rehab Deferred Loan (RRDL) program, which is geared toward smaller projects in greater Minnesota. Authorized in 2011, the program can make loans of up to $300,000 at zero percent interest and is available for owners who are seeking financing for the moderate rehabilitation of their developments’ residential units. 5

“There are a lot of mom-and-pop housing operations in rural Minnesota, projects with fewer than ten units,” Heitlinger says, “and we were finding that a lot of the older properties had deferred maintenance needs. The RRDL program was created to fund rehab work at these projects.”

In addition to the RRDL program, Heitlinger points out three rural-preservation-oriented policy changes that resulted from discussions among Minnesota’s affordable housing organizations: the decision by Minnesota Housing to dedicate $300,000 annually in Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs) for rural rehabilitation and preservation projects; the decision by the same agency to give more favorable consideration, as part of the LIHTC allocation process, to projects that seek to preserve affordable developments;6 and the decision by the funders that use the Consolidated RFP to give priority to projects that have critical physical condition needs, have owners with limited capacity to address identified issues, or are in danger of converting to market rate.

Preservation efforts elsewhere

Efforts to preserve affordable housing properties range in intensity from state to state. Tracy Kaufman, the director of the National Preservation Initiative of the National Housing Trust, points to a handful of cities and states, among others, that have launched particularly effective collaborative preservation campaigns: the states of Ohio, Washington, Michigan, and Massachusetts, and the cities of Chicago and Portland (Ore.).

“And Minnesota, too, is way out in front of a lot of states in terms of coordinating affordable housing preservation efforts,” she says. “All of these areas have different approaches, but they’re all great models for what other cities and states can do to more effectively and strategically target their limited resources.”7

In the Ninth Federal Reserve District, affordable housing stakeholders in Montana started a conversation a few years ago about the issues associated with preserving and stabilizing the state’s inventory of Section 515 developments. Personnel from USDA RD-Montana, the state’s network of human service agencies known as Human Resource Councils (HRCs), and the Montana Board of Housing, among others, have been meeting to discuss the options available for these preservation efforts.

Jim Morton, executive director of District XI HRC, which serves Mineral, Missoula, and Ravalli counties, says that many current Section 515 property owners in Montana are past retirement age and would like to transfer their developments to nonprofits, but doing that would create a tax liability that is often too high to bear for some.

“These are folks in their 70s and 80s who want to do the right thing and keep the affordable developments going but don’t have the means to pay the costs associated with a transfer,” he says, explaining that many owners would owe money because they declared depreciation of the property on previous tax returns. “This is certainly a problem in Montana, but we’ve started looking for solutions.”

In Michigan, the state housing finance agency specifically considers Section 515 properties when it allocates LIHTCs and, of the total LIHTCs available each year, 10 percent is set aside for projects in rural areas. The LIHTC program has a competitive allocation component, for what are called “9 percent tax credits,” and a non-competitive awarding process, called “automatic 4 percent tax credits.” According to Andrew Martin, the allocations manager for the Michigan State Housing Development Authority (MSHDA), his agency tries to direct some proposals for the competitive 9 percent tax credit program to the non-competitive 4 percent tax credit program; the 4 percent tax credit program typically works better for larger developments, which are more often found in metropolitan areas.

“This frees up the pool of 9 percent tax credits to use for smaller, more rural projects,” he says, noting that MSHDA has allocated tax credits to 37 Section 515 properties since 2010. “For the Section 515 properties, keeping the rental assistance going is key to all of these deals.”8

In the absence of collaboration

Heitlinger, of Minnesota Housing, contends that without the cooperation and coordination among the members of the Greater Minnesota ISG, the efforts to stabilize and preserve affordable rental developments in rural Minnesota would be far less effective.

“Overall, we would do fewer projects, with less information, and with a less synchronized approach,” she says. “We currently get three or four times more requests than we can actually fund, so you really want to make strategic decisions about what you’re funding.”

Over the past decade, the Greater Minnesota ISG has helped preserve 26 Section 515 projects in Minnesota containing approximately 640 units. Sixteen of those units belong to the Prairie Rose, Skip Duchesneau’s recently purchased and totally rehabbed development in northern Minnesota. Had it not been for the phone call he took from a Greater Minnesota ISG member that day, those units might not have been among the hundreds of units preserved.

“It really helped that people from Greater Minnesota Housing Fund and HUD were both behind this,” he says.

Endnotes

1 This figure, provided by HousingLink, represents Minnesota’s unit total for 2013.

2 This number represents the total number of subsidized affordable rental units in 2013 in greater Minnesota, reported by HousingLink. It was calculated by subtracting the number of subsidized affordable housing units in the Twin Cities metropolitan area, reported to be roughly 64,000 in 2013, from the number of subsidized affordable housing units statewide, reported to be approximately 110,000.

3 For more on Section 515 mortgage criteria, visit rd.usda.gov/programs-services/multi-family-housing-direct-loans.

4 The historic total of affordable rental units financed under the Section 515 program is listed on the Housing Assistance Council’s Section 515 information page at ruralhome.org/storage/documents/rd515rental.pdf. The figures on properties currently remaining in the program are from USDA RD’s Multi-Family Housing Occupancy Statistics Report as of September 2014.

5 Visit www.mnhousing.gov for more information.

6 The LIHTC is a federal tax credit program designed to spur private investment in affordable housing. For more on LIHTCs and how they are allocated, see “LIHTC priorities capture state affordable housing needs” in the April 2015 issue of Community Dividend.

7 For information on preservation policies for all 50 states (and some cities), visit the National Housing Trust’s PrezCat web site at prezcat.org.

8 Nearly 20 states set aside a portion of their 9 percent tax credit for rural projects. For more on this, see prezcat.org.