In much of Indian Country, the number of jobs per inhabitant is on par with nearby county areas, according to new research supported by the Center for Indian Country Development (CICD). However, Indian Country’s jobs are skewed towards a few large industries, especially Arts-Entertainment-Recreation and Public Administration. This concentration in industries closely tied to gaming may indicate a need for more economic diversification in Indian Country as casino revenues have slowed since 2005.

The findings about Indian Country jobs appear in the new CICD Working Paper 2018-01, “Reservation Nonemployer Establishments, Alone and in Combination with Employer Establishments: Data from the U.S. Census Integrated Longitudinal Business Database,” by Randall Akee (UCLA), Elton Mykerezi (University of Minnesota), and CICD Advisor Richard M. Todd. Using confidential business records from the U.S. Census Bureau, they build on their previous research on jobs at employer establishments (i.e., workplaces with employees) by adding in jobs at nonemployer establishments, such as sole proprietor businesses. This provides a more complete measure of all jobs in their study group of 277 federally recognized Indian reservations and 514 nearby off-reservation county areas.1

Because of the confidential nature of the underlying data, only broad averages can be publically released. This method obscures differences among reservations, such as between relatively affluent reservations with large casinos adjacent to population centers and many much more remote and less affluent reservations.

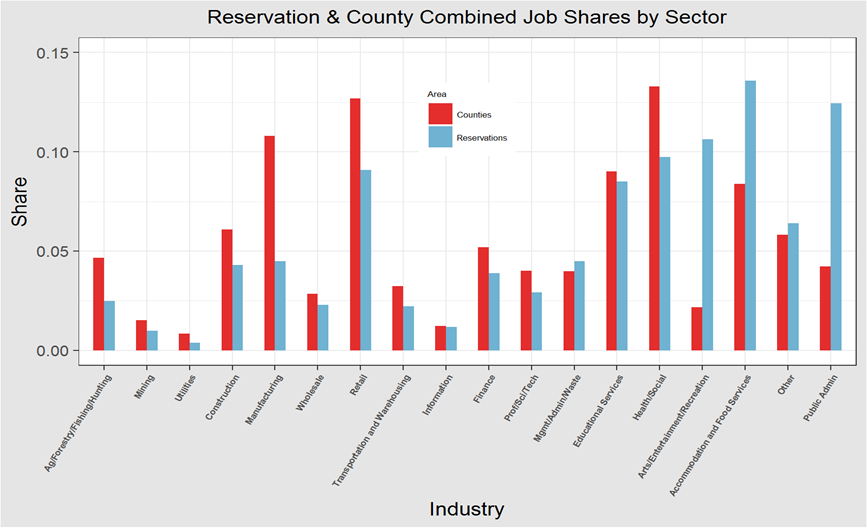

When averaged across all the included reservations, both prosperous and poor, reservation communities as a group have about the same number of jobs per inhabitant as found, on average, in the group of nearby county areas. However, the mix of jobs across industries is quite different between the reservations and the nearby county areas, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

This figure shows the percentage of total jobs by 18 industrial sectors for the study’s reservations and nearby county areas. For example, the red bar for “Manufacturing” shows that factory jobs account for over 10 percent of all jobs in the nearby county areas but less than 5 percent of all jobs in the reservations. By contrast, the share of jobs on reservations is relatively high in industries such as Public Administration; Accommodation and Food Services; and especially Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation. This is consistent with the important role that the casino industry has played in reservation economic development. Casinos and casino hotels are classified in the Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation industry itself. In addition, a tribe’s casino revenues can fund expansion of tribal government employment (Public Administration jobs), and the customer traffic that casinos generate may boost jobs at restaurants, non-casino hotels, and other Accommodation and Food Service establishments.2

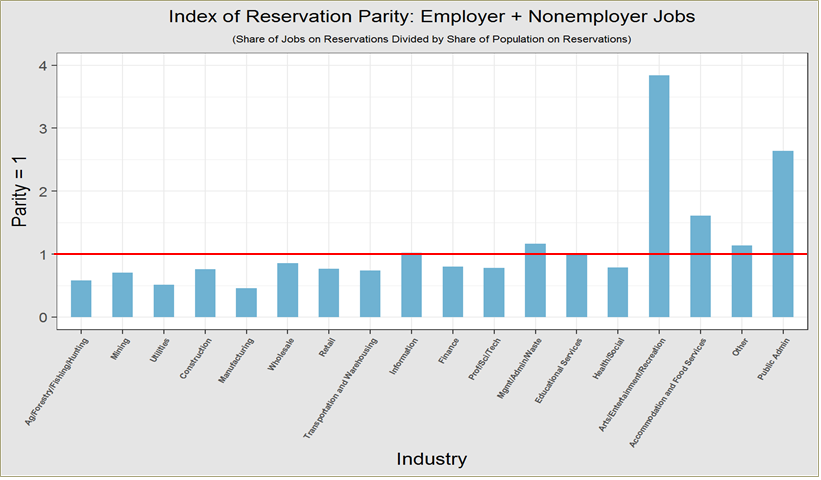

Figure 2 shows sectoral concentration reservation jobs somewhat differently, but with the same basic result. It shows a “parity ratio” for jobs, defined as the reservations’ share of the jobs in that industry (for the study’s reservations and county areas combined) divided by 0.082, which is the reservations’ share of the combined reservation-plus-county-area population. Ratios below one indicate that reservations have fewer jobs per inhabitant than the county areas do, and ratios above one indicate the reverse. The parity ratio is below one for most industries and near one for a few others. However, in the same three industries that stood out in Figure 1—Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation; Public Administration; and Accommodation and Food Service—the parity ratio is far above one, indicating many more jobs per inhabitant on reservations as compared to counties.

Figure 2

Akee, Mykerezi, and Todd primarily report these and other related results and do not focus on their policy implications. However, the rapid growth in total tribal gaming revenues, which contribute to the patterns shown above, slowed significantly after 2005.3 Should growth in tribal gaming revenues remain slow, Indian Country will need to look to other industries to sustain its economic development. The patterns documented here suggest opportunities to expand in the many industries in which Indian Country jobs per inhabitant remain well below their levels in nearby county areas. According to Akee, Spilde, and Taylor, “tribal governments will need both to diversify the tribally owned sector and to develop policies that encourage private business formation and recruitment on the reservations as well.”4

For complete findings, see CICD Working Paper 2018-01, “Reservation Nonemployer Establishments, Alone and in Combination with Employer Establishments: Data from the U.S. Census Integrated Longitudinal Business Database”.

Endnotes

1 The omitted federally recognized reservations are mostly very small and are omitted due to lack of related data needed for the analysis. However, the largest reservation, Navajo, is also omitted, because it would otherwise dominate the results.

2 See Akee, R. Q., Spilde, K. A., & Taylor, J. B. (2015). “The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and Its Effects on American Indian Economic Development.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 185-208.

3 Figure 2 in Akee, R. Q., Spilde, K. A., & Taylor, J. B. (2015). “The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and Its Effects on American Indian Economic Development.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 185-208.

4 Akee, R. Q., Spilde, K. A., & Taylor, J. B. (2015). “The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and Its Effects on American Indian Economic Development.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), p. 203, with reference also to Cornell, Stephen, Miriam Jorgensen, Ian Record, and Joan Timeche. 2007. “Citizen Entrepreneurship: An Underutilized Development Resource.” In Rebuilding Native Nations: Strategies for Governance and Development, 197–222. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.