At Rob McDonald’s Pizza Ranch restaurant in Elk River, Minn., there used to be a worker on the job every day whose main task was to take orders by phone.

But, recently, McDonald was able to reduce the hours for that job to just the weekends thanks to the growing number of customers ordering online. As of last year, about a quarter of pickup and delivery orders were online, and he expects that to double this year.

“Hopefully, that’s the direction we’re moving in, 75 percent online and 25 percent call-in,” McDonald said. “We wouldn’t have to have that person standing back there answering the phone.”

That could mean another set of hands in the kitchen or another person to greet customers, or it could just mean less money spent on labor.

Restaurant employees are among the more than 1.3 million workers in the Ninth District whose jobs are at high risk of disruption over the next several decades, according to a recent Brookings Institution report and data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s more than a quarter of the workforce. Many aren’t the stereotypical factory jobs threatened by robots, but jobs such as restaurant servers and drivers facing advanced algorithms. (For the story on robot-driven automation, see Motivated to automate.)

This is very much in line with the rest of the nation.

Though computer-driven automation has disrupted labor markets for decades, the Brookings report warns of even greater disruption ahead as technologies mature and computers enter the era of artificial intelligence (AI), when machines can understand voice commands and cars drive themselves. As in the past, new jobs will likely be created as the economy transforms, but many workers could see their livelihood upended in the process, the report said, the latest of many to sound the alarm in recent years.

Defining risk

“High-risk” doesn’t mean robots and computers will replace workers wholesale, the Brookings report said. While some jobs could be done entirely by machines, a vast majority would still require people, albeit fewer of them. The impact is expected to fall disproportionately on workers in low-paying jobs and, in general, rural areas would be harder hit than metro areas, which have more diverse economies.

Brookings researchers based automation risk on the tasks required in each job. It’s easier to automate tasks governed by simple rules, such as spraying paint on a car bumper following preprogrammed contours. It’s much harder to automate tasks with complex rules, such as social interactions, or require manual dexterity and senses unmatched by machines.

The report defined high-risk jobs as those in which 70 percent or more of the tasks are easy to automate. Low-risk jobs are those in which 30 percent or fewer of the tasks are. Medium-risk jobs fall in between.

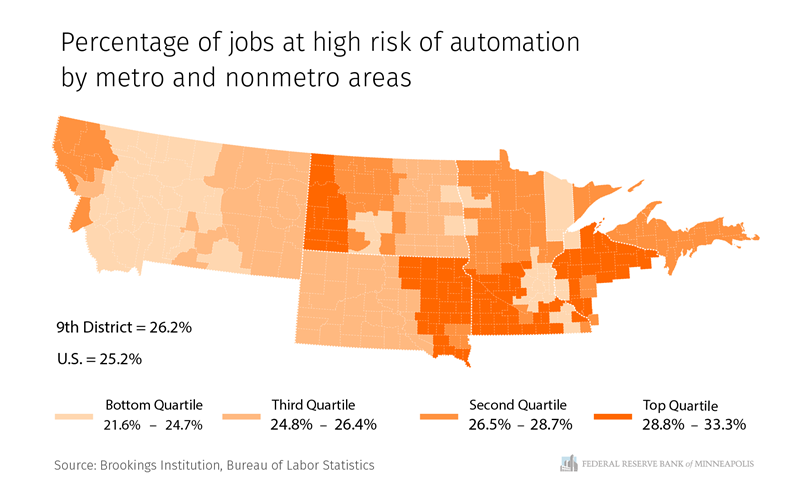

In the Ninth District, 26 percent of the existing jobs are at “high risk” of automation over the next several decades, a percentage point higher than the national average.

Though more than a third of the high-risk jobs are in the Twin Cities metropolitan area, the highest concentrations are in rural areas of the district, with nonmetropolitan counties in western Wisconsin and far western North Dakota leading the way. About a third of the jobs in those counties are at high risk. Especially numerous are truck drivers and restaurant workers.

Those are common jobs in metro areas, too, but there they are balanced out by the larger share of low-risk jobs, such as registered nurses and personal care aides. There are, for example, four times as many truck drivers per 1,000 workers in western Wisconsin as in the Twin Cities. In fact, the Twin Cities, Rochester, and Mankato (Minn.) take the lead with more than 40 percent of jobs at low risk. The Ninth District average is 38 percent, and the national average is 39 percent.

On average, 47 percent of the tasks involved in jobs throughout the district are easy to automate or will be in the foreseeable future, a percentage point higher than the national average.

Labor constraints

For now, automation doesn’t seem to be an immediate threat to district workers, with many counties reporting labor shortages. The annual unemployment rate in the district was 3.1 as of February 2019.

In Richland County, N.D., where unemployment was 2.7 percent, industrial-belt maker WCCO Belting had to increase automation significantly to keep growing, according to President and CEO Thomas Shorma.

Many workers left for other jobs in the competitive labor market, and he reasoned that he could raise wages if WCCO produced more with fewer workers. “We have to produce more to pay more,” he said he told workers in 2014.

Within three years, he said, the company made 20 percent more belts with 20 percent fewer workers, most leaving through attrition. To give an example of automation, he said, an in-house engineer redesigned an extruder so that the feed was automatic, eliminating the need for one of two workers manning that machine.

Automation doesn’t always eliminate jobs, however. It could change how jobs are done.

Sanford Health, a big regional health care group, bought a pill-dispensing system for its Sioux Falls, S.D., hospital in 2011 to improve safety. The machine uses barcodes to look up prescriptions and robot arms to fetch the correct pills.

Pharmacy Director Mike Duncan said it’s 99.97 percent accurate, which is a few percentage points better than a human and enough so that a pharmacist doesn’t have to double check; Sanford got an exemption from state requirements. The 0.03 percent error rate mostly involves the robot arm accidentally dropping a package, he said, which isn’t a danger to patients as would be the case with too many pills or the wrong ones being administered.

He said the pharmacy employs the same number of pharmacy technicians as before because they’re needed to run the machine, but pharmacists, who used to have to check some 3,000 doses a day, now have time to give patients more attention.

“They are actually able to spend more time looking more at the clinical side of things, checking does the patient need [this drug] and was it in the right dose?” Duncan said. “Do they have any contraindications? Do they have any drug interactions?”

Uncertain future

The examples mentioned so far appear to represent the maturing of computer technology from the 1980s and 1990s. To see how AI, characterized by machine learning and big data, will actually impact the labor market, the Brookings report looked to the past.

Between 1980 and 2016, the number of jobs actually grew in spite of automation. But the kinds of jobs available changed. There were fewer factory and clerical jobs that provided baby boomers with middle-class incomes with minimal education requirements; those jobs featured many of the repetitive tasks machines excel at. Much of the job growth was either in lower-wage, minimal education jobs—think of most service industry jobs—or higher-wage, higher education jobs—think tech workers.

The Brookings report suggests that machines will soon excel at many of those lower-wage jobs as well.

But how it will all shake out in the end is hard to tell.

For one, automation is likely to create many new jobs, but it’s hard to predict what those might be. Who in the 1980s could have foreseen job titles such as social media coordinator and search engine optimization specialist? For another, just because a task can be automated doesn’t mean it will be. The investment can be too costly or disruptive for some businesses.

With boomers retiring fully, a smaller workforce might mean workers will remain in high demand despite machines taking over more jobs.

At Pizza Ranch, McDonald foresees more ways automation could change his business. Kiosks, which essentially bring the online ordering experience in-store, are all the rage in his industry these days as consumers grow accustomed to ordering from machines. That, he said, could reduce the pizzeria’s need for a greeter.

Tu-Uyen Tran is the senior writer in the Minneapolis Fed’s Public Affairs department. He specializes in deeply reported, data-driven articles. Before joining the Bank in 2018, Tu-Uyen was an editor and reporter in Fargo, Grand Forks, and Seattle.