As the federal government shutdown continues, we at the Center for Indian Country Development believe the dollar estimate of the current impact on Indian Country is substantial and outsized, and the actual impacts extensive and deep. We cannot make a precise calculation due to the complex federal funding streams, variance of the shutdown by federal agency, by tribe, and the difficulty with obtaining data. For now, our best source of useful information comes from monitoring news stories and reaching out to tribal community leaders.

But here’s what we know…

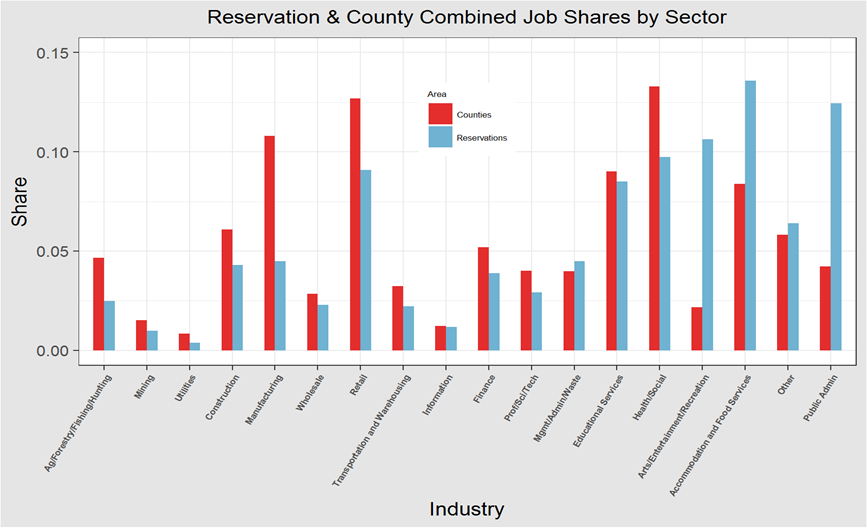

At a broad level, government employment is disproportionately high in Indian Country. The Public Administration, or government sector, accounts for about 12.5 percent of all jobs in the group of 267 federally recognized reservations we’ve studied (we omitted the most populous reservation, Navajo, where OnTheMap puts the share at about 30 percent). The corresponding figure in our group of 514 nearby county areas was about 4 percent.

Although the Public Administration sector does not include tribal casinos (see the Arts/Entertainment/Recreation sector below), it does include tribal and federal, and potentially county and state employees. However, given that reservations rely heavily on federal funding (often pursuant to treaty provisions), we assume that their disproportionate reliance on government jobs extends to federal government jobs, such as in the Bureau of Indian Affairs or the Indian Health Service.

Richard M. Todd, “Industry Concentration of Jobs Highlights Economic Diversification Opportunity in Indian Country,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (May 31, 2018). https://www.minneapolisfed.org/indiancountry/research-and-articles/cicd-blog/industry-concentration-of-jobs-highlights-economic-diversification-opportunity-in-indian-country

In addition, tribal governments depend substantially on federal funding to deliver services on behalf of federal agencies under contract-like “compacts” with these agencies. We assume that the combined dependence on direct federal jobs and federally funded jobs is distinctly higher on reservations than in most rural counties (where it is already higher than in most urban areas).

Precise measurement of the impact on workers’ pay checks is not easy. Each agency makes its own determination as to which workers can be paid under existing appropriations or other funding sources, which are unpaid but excepted (and thus required to work without pay or to be on call), and which are furloughed without pay. The results vary widely. For example, the majority of employees at the Bureau of Indian Affairs are furloughed, but only a small percentage at the Bureau of Indian Education.

In addition, we cannot assume that federal Indian education is proceeding normally, even though many BIA activities are curtailed. It’s not that simple. The BIE funds both federal and tribally run schools, or contracts for educational services. We lack good information on what is happening to these educational services, but we think that some of these payments have either ceased or are about to. In some cases tribes seem to be providing at least temporary funding to affected schools, but that may not last long.

Also, the tribal and BIA staff who maintain and plow reservation roads are furloughed. So school buses may not be able to get children to and from school, as we hear is happening on the Navajo reservation. As this example demonstrates, the shutdown services of one unit may undercut the availability or quality of services provided by nominally open units that depends on the former unit’s services. This affects the unpaid workers too; they might want to bridge their cash flow gap by drawing on funds in their Individual Indian Accounts, but we hear that the Office of the Special Trustee has furloughed the staff that process disbursements from those accounts.

All told, the federal government shutdown is affecting Indian Country in substantial and unique ways.