Running a business is hard. It involves spinning numerous plates simultaneously—inventory, financing, human resources, logistics, capital investment, marketing—you get the idea. A multitasking balancing act if ever there was one.

And amid all that plate-spinning, imagine having an elephant tossed in—not a nice one, either—and you might start to understand what many businesses are facing with the COVID-19 outbreak. The pandemic has hit the economy—and its millions of businesses—with unexpected and outsized speed and impact.

A new Minneapolis Fed survey of businesses across the Ninth District reveals that, given many uncertainties related to the COVID-19 outbreak, businesses have developed a bit of vertigo after getting blindsided, not from a bad business decision or a sectoral downturn or a poor overall economy (not directly or immediately, at least), but from being run over by a virus.

“We don’t know what the end looks like yet,” said a large North Dakota manufacturer in our survey. The firm’s March revenue dropped compared with earlier in the year, and further declines are expected in April. All hiring has stopped for open positions, and some positions have already been cut. “[It’s] very hard to manage a business like this. Uncertainty means you don’t spend or hire on anything other than current day-to-day operations.”

These and many other insights came from a survey garnering more than 1,800 responses from a broad cross section of businesses in every district state. The Minneapolis Fed conducted the survey last week (Wednesday, April 1, to Friday, April 3) via email through partnerships with local and state chambers of commerce and regional economic development organizations.

This survey was a follow-up to a mid-March survey gauging immediate impacts of the virus outbreak. Respondents reiterated some findings from two weeks earlier, namely, that the economic impact of COVID-19 has been fast, significant, and negative. Additional analysis on this second survey found that certain types of businesses are feeling the effects more immediately and deeply than others. New questions also found tempered optimism toward new federal and state emergency aid programs, which are designed to help stabilize firms and workers during this period.

Respondents also continued to share their situations, challenges, and concerns in unprecedented volume; more than 4,300 open comments were submitted. A sliver of those comments will help illuminate some of these issues. But the Minneapolis Fed continues to work on alternative ways to spotlight and amplify the challenges that district businesses voiced through this survey.

Beware the ides of March

Firms were starting to see COVID-19 impacts early in March, and effects have accelerated over the course of the month as state and local governments began limiting social and business crowds, introducing social distancing recommendations, and eventually closing nonessential businesses.

By the end of March, 43 percent of survey respondents across the Ninth District said monthly revenues fell by half or more compared with monthly averages in January and February.

A Twin Cities chiropractic office said that it experienced a revenue drop of 85 percent following the shelter-in-place pronouncement by Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz—this despite being designated an essential business and being allowed to stay open. “And it will get worse,” the respondent predicted.

No state, or industry sector, escaped impact. But financial effects have not been spread uniformly. For example, a slightly higher share of firms in Minnesota, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and Wisconsin saw poor sales in March compared with the Dakotas and Montana—likely because statewide restrictions and closures came to those former states earlier, and numerous respondents noted a steep drop-off of business as the weeks progressed in March.

Certain types of businesses are also more directly and immediately in the economic path of the outbreak. Entertainment, food, accommodation, and retail businesses were most likely to report revenue losses in March, as well as higher levels of revenue loss. Banks, manufacturing, and construction saw modestly smaller effects on March revenue. Firm size was also inversely related to revenue performance; smaller firms were more likely to see large revenue declines in March.

With falling revenues and uncertainty over when that might change, 46 percent of respondents districtwide said their firm had cut some staff in March. The good news is that firms expected that to increase only marginally (to 53 percent) by the end of April. As one might guess, workforce reductions were slightly higher in eastern district states, where revenue declines have been somewhat larger.

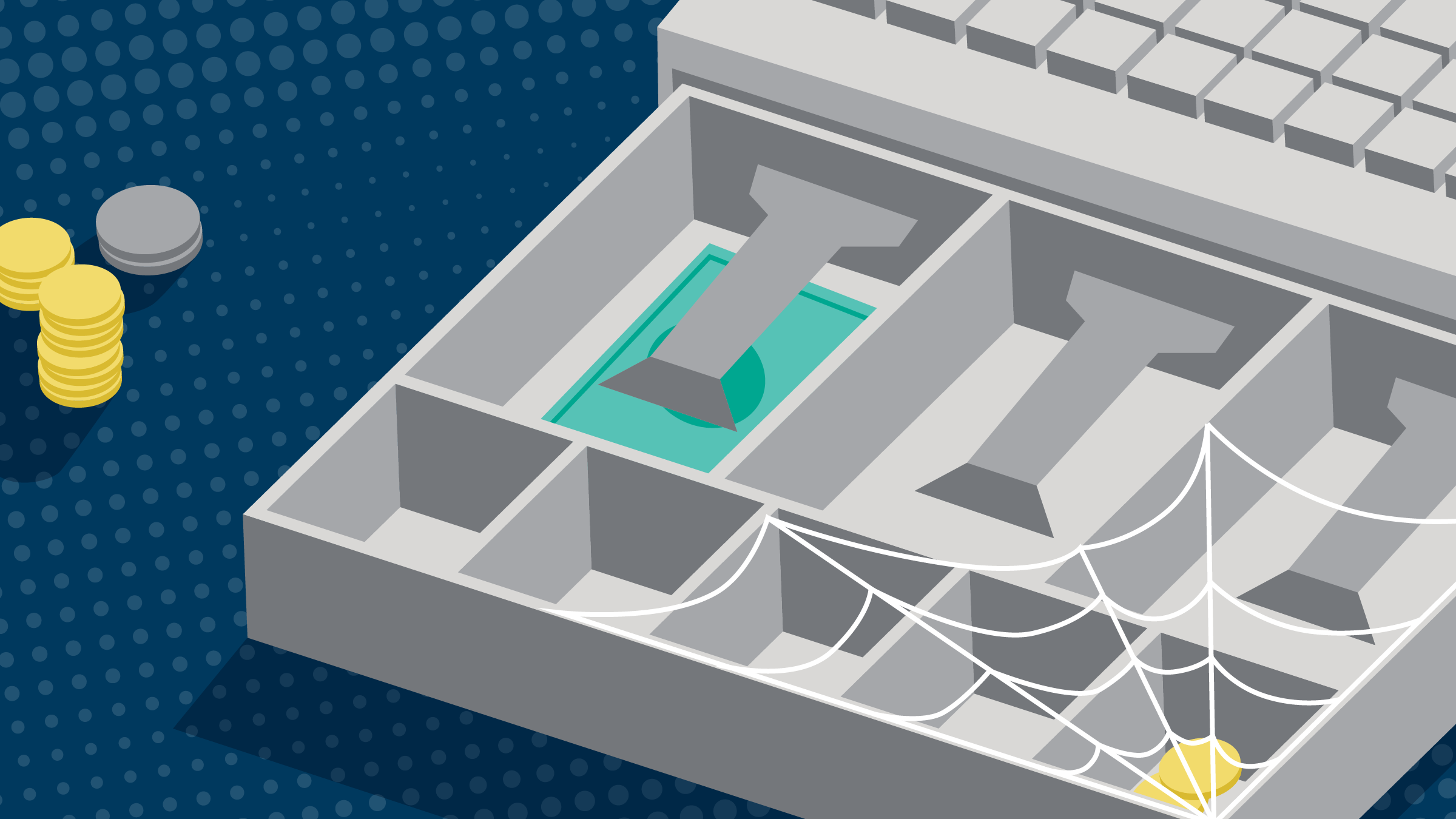

The uncertainty also spills into solvency—how long businesses think they can keep the lights on under the current environment. Five percent of respondents reported a razor-thin margin—survival for less than one month. Another 27 percent believe they have a one-to-three-month cushion. Those seeing the fastest revenue drops—entertainment, food, accommodation, retail— reported the thinnest financial cushion. Larger firms were also much more likely to have a longer, safer leash on solvency, which is what economists would predict given that, as a group, they should have greater efficiencies of scale, higher margins, and better access to capital.

Uncle Sam needs you … to hold on

Federal and state governments have rushed to pass emergency aid, including a $2 trillion package pass by Congress in late March to help firms survive and to keep workers either working or not starving if they’re laid off.

Whether these efforts succeed will be closely watched in the coming weeks and months. Early sentiment among survey respondents was hopeful, but not over the moon. A little more than half (54 percent) had some level of optimism that emergency aid would help their particular business, and optimism was stronger (63 percent) that aid would help businesses in general. District states also exhibited modest differences in sentiment; for example, optimism in the Dakotas and Montana was about 10 percentage points higher than among Minnesota and U.P. respondents.

For many, the aid is crucial. A small retailer in greater Minnesota, in business more than 10 years, said it recently restructured with plans for the future. “I was starting out this year in debt, but felt confident that it would be paid off quickly due to steadily increasing sales. Now I am faced with the possibility that I may have to close if I do not get much needed assistance.”

Businesses districtwide face a gauntlet of tough decisions in the coming weeks and months—decisions that have to be made with frustratingly imperfect information.

A lodging firm in greater Minnesota noted that it had savings “that could be used to get us through several months,” but that it also had concerns “about throwing good money after bad money.” It has already canceled planned upgrades to its facility and put off equipment upgrades “due to the uncertainty of the situation.”

The company’s savings are typically used “to get us through the normal slow time” in the fall and early winter. If savings are used now to survive the coming months, and summer demand doesn’t materialize, spending those savings “would only prolong the inevitability of the business going bankrupt.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.