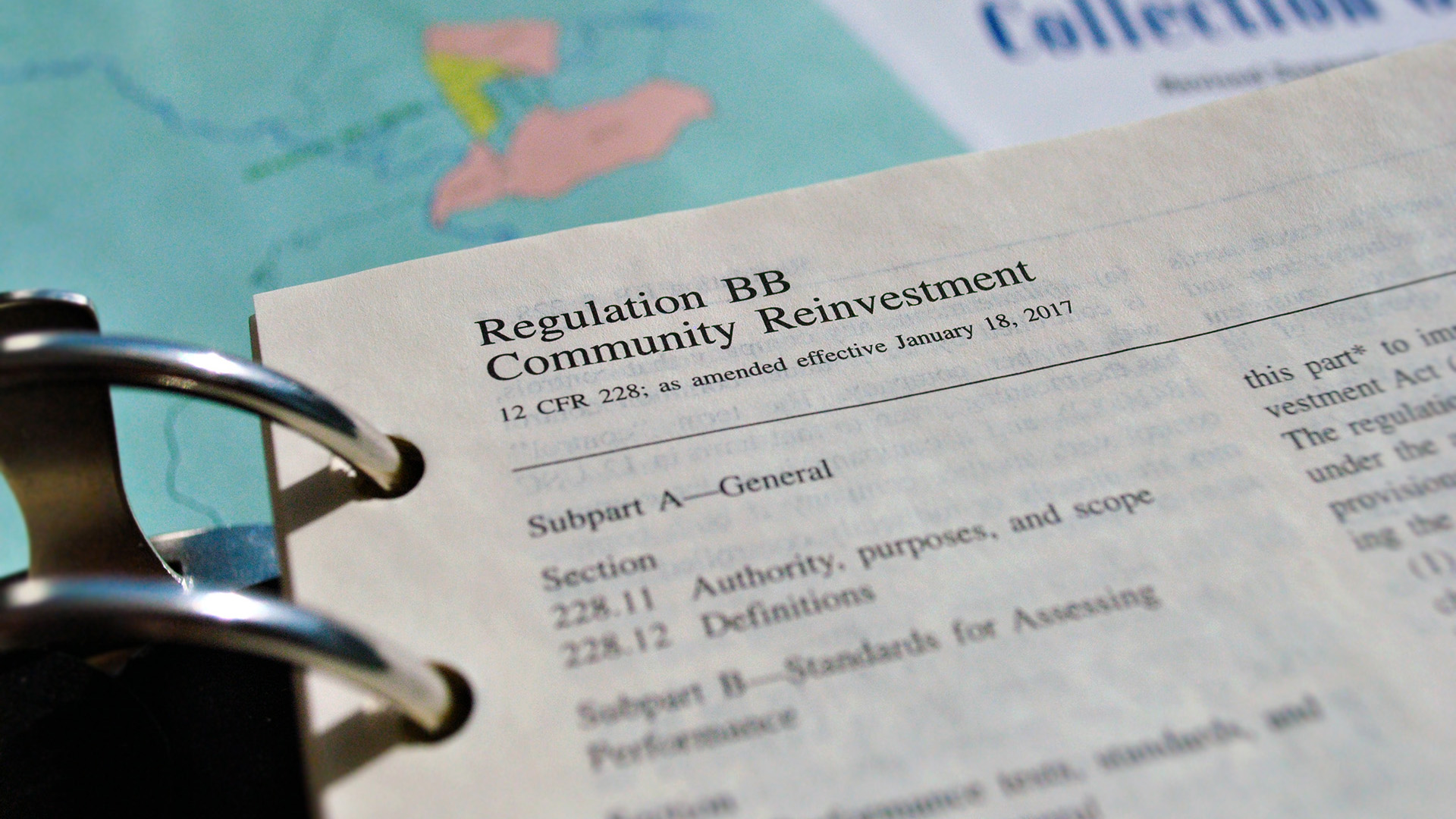

Indian Country is home to thriving entrepreneurs and strong communities, but many of its businesses and households struggle to access affordable credit.1 The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA)—a 1977 federal law that requires banks to meet community credit needs—may help. The Federal Reserve is currently soliciting feedback from the public on proposed, major changes to the CRA.2 Here, we examine features of the CRA’s current implementation framework with an eye toward how it may improve access to credit in Indian Country.

Who was the CRA intended to support?

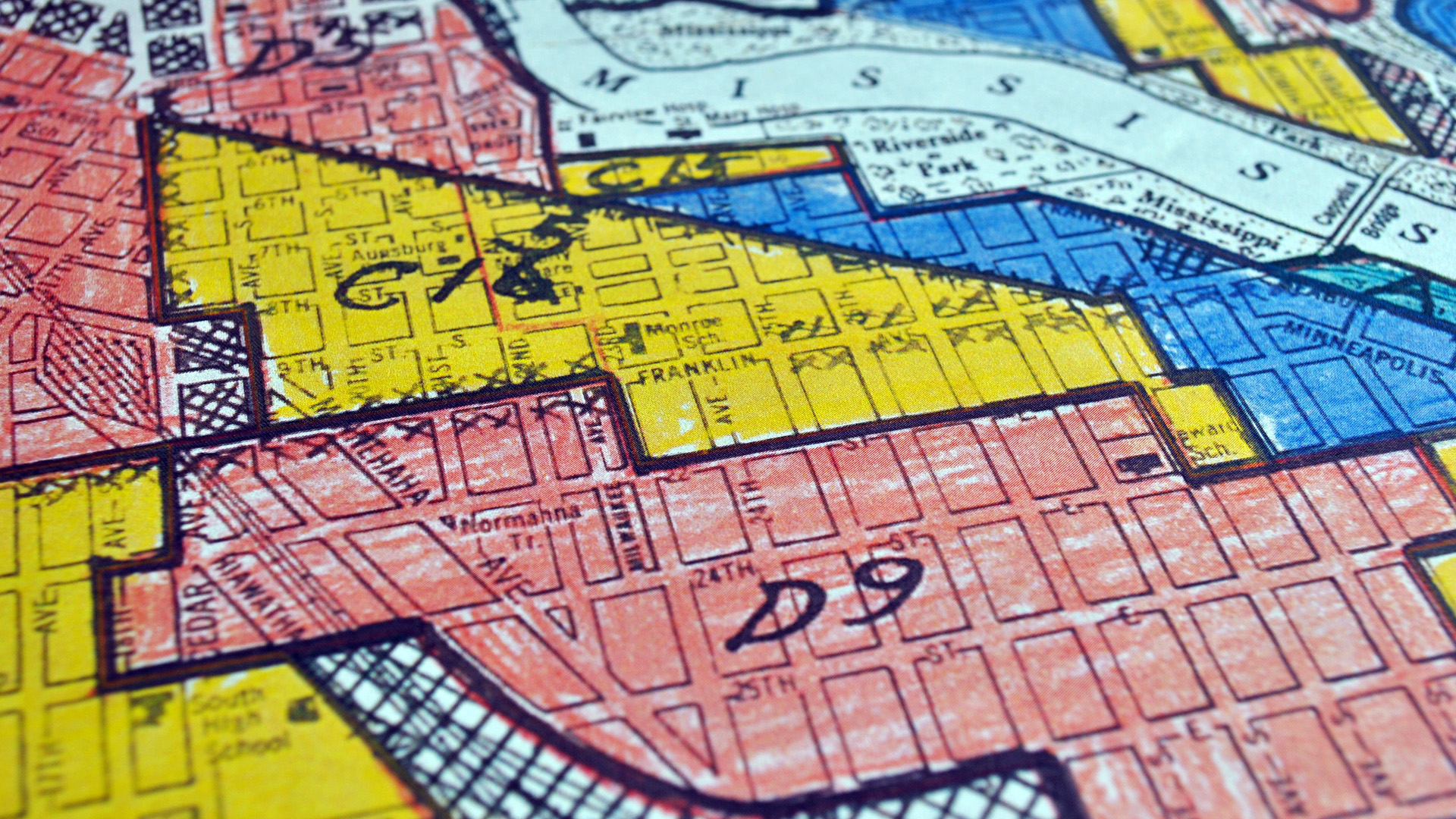

Congress passed the CRA in response to unfair lending practices like redlining, where lenders refused to make loans in entire neighborhoods. The law empowers federal financial regulatory agencies, including the Federal Reserve, to evaluate a bank’s lending, retail, and community development activities to ensure it is meeting the credit needs of the community.3 Examiners from the regulatory agencies periodically assess—and rate—whether those activities meet the credit needs of low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities and individuals, small businesses, and small farms.4

While the CRA is race-neutral on its face, its focus on LMI geographies means that it can be particularly relevant for communities of color. For example, in 2018, about 45 percent of Native American households were in census tracts that CRA standards consider LMI, distressed, or underserved, compared to 32 percent of the overall population.5

How are banks evaluated?

The evaluation process for the CRA is complex, involving four main components: assessment area delineations, a lending test, community development tests, and ratings.

Assessment area delineation

A bank’s assessment area, a critical feature of its CRA examination, contains the census tracts where the bank’s CRA evaluation will focus. It is a map of the communities whose credit needs a bank is expected to help meet. Banks determine their own assessment areas, though they are reviewed by a bank’s CRA evaluator for compliance with regulations.

The assessment area must include the areas where the bank has its offices and deposit-taking ATMs. It also must include the areas where the bank has originated a substantial portion of its loans, and cannot arbitrarily exclude LMI areas or reflect discrimination. There are also some restrictions and requirements related to the geographic boundaries of the assessment area.

One challenge with the assessment area definition for Indian County is that it is primarily brick-and-mortar driven. To include Indian Country in an assessment area, there must at least be some office locations geographically near those areas. If an area is far from a bank’s branches, banks must meet additional requirements before receiving CRA consideration for lending or community development activities in that area.

Lending test

During the lending test, examiners evaluate the bank’s primary lending activities. Those could include mortgage, small business, small farm, and other loans the bank made since its prior CRA exam. Examiners analyze the loans based on individuals’ income levels, or the size (based on revenue) of farms or businesses borrowing money. Examiners also evaluate the geographic distribution of the bank’s loans, particularly the level of lending in LMI census tracts.6

Native CDFI Network

Community development tests

Examiners also review the bank’s level of qualified community development activity.7 For CRA purposes, community development activities can take the form of loans, grants, or investments. They can also include community service provided by bank employees—so long as that service is directly related to provision of financial services. If bank employees volunteer by preparing food in a homeless shelter, for example, their service would not qualify for CRA consideration. On the other hand, a bank executive might be performing a CRA-eligible activity if she serves on a board for a nonprofit and advises on programs that extend credit to underserved communities.

The language of the law and its rules allows banks to pursue a wide range of community development activities and still receive CRA consideration. For example, in recent years, Federal Reserve Banks have produced materials highlighting the potential for community development activities in areas as wide-ranging as workforce development, public health, and broadband. Community development loans and investments must be provided in a safe and sound manner by the bank.8

According to one Native American leader we spoke with, Indian Country offers ample opportunities for banks to support community development.

“I can think of countless Native nonprofits that are doing great community development work in Indian Country,” said Jackson Brossy, executive director of the Native CDFI Network. “There’s almost always a connection to economic empowerment.”

CRA regulations do not necessarily prioritize one type of community development activity over any other, so on-the-ground perspectives can help steer resources where they are likely to have the biggest impact. Brossy said that relationships with community leaders in Indian Country can help banks understand where needs—

and opportunities—are greatest.

An analysis of the CRA loans originated between 2013 and 2017 shows that, on average, there are fewer CRA loans made per person in counties with a majority American Indian and Alaska Native population compared to all other counties.9

Ratings

Each bank receives a public CRA rating of Outstanding, Satisfactory, Needs to Improve, or Substantial Noncompliance based on its performance.10 Banks may have multiple assessment areas or operate in numerous states. These performances are aggregated to determine the overall rating. Banks also receive individual ratings for their performance in each state and multi-state metropolitan area, as applicable. Comparisons of the bank’s performance against demographic factors, peer banks, competition, credit needs, and impact of community development activities all factor into the rating. Most banks receive a Satisfactory rating.11

How does community input feature in the CRA?

Every CRA examination is informed by a performance context, defined in the regulation as “a broad range of economic, demographic, and institution- and community-specific information that an examiner reviews to understand the context in which an institution’s record of performance should be evaluated.”12

Performance contexts draw on quantitative data, but are also informed by qualitative feedback. This feedback can come through two primary channels. First, community members can submit comments relevant to a bank’s CRA performance. For example, a community organization could write about a bank’s investments in its neighborhood, or describe a need that the bank is not meeting. These comments can be submitted to a bank directly, or to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.13

Second, as part of a CRA evaluation, examiners interview community leaders in a bank’s assessment area. For example, examiners may meet with tribal leaders if a bank’s assessment area includes or is near an Indian reservation. These conversations ideally provide examiners with a broader understanding of local economic or other factors that may impact credit needs and the availability or provision of credit to meet those needs.

Embracing opportunities, building relationships

Tony Walters, executive director of the National American Indian Housing Council, sees potential for lending in Indian Country to expand, if the parties involved would embrace the opportunities more. But if banks are not driving the conversation, the CRA may not be top-of-mind for tribal leaders, he said. He added that banks often don’t seem to prioritize investments in Indian Country, even though many parts of Indian Country offer opportunities for CRA-eligible loans.

Establishing or strengthening relationships in Indian Country can be key to identifying opportunities to pursue CRA-eligible loans and community development activities. But the value of relationships goes far beyond that, said Jeff Bowman, president and CEO of Bay Bank, located in Green Bay, Wisconsin. The bank is wholly owned by the Oneida Nation, and received an Outstanding CRA rating in its most recent evaluation.

“Serving our communities is so baked into our organization’s mission that we don’t even plan around getting CRA credit,” said Bowman, the bank’s president and CEO. Bowman credits his bank’s CRA success to his staff’s awareness of their clients’ banking needs. He said the same behavior that has resulted in outstanding CRA scores allows the bank to find opportunities to grow overall.

“You have to adapt to your community,” he continued. “If you are just showing up in Indian Country with products designed to work somewhere else, it’s not going to cut it.”

Modernizing the CRA to better serve Indian Country

While the overwhelming majority of banks are rated Satisfactory or better in meeting their communities’ credit needs via the CRA, opportunities still exist to improve access to credit for communities in Indian Country and beyond. To that end, the Federal Reserve is in the process of modernizing the CRA. The Center for Indian Country Development at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis is coordinating outreach to Indian Country leaders to gather input. Feedback from Indian Country is critical in ensuring that CRA modernization recognizes diverse perspectives and experiences, and it will assist the Federal Reserve in making the CRA more effective for low- and moderate-income communities. For more information on the modernization effort, visit the Minneapolis Fed’s CRA web page.

Endnotes

1 For a detailed discussion on access to credit in Indian Country, see Access to Capital and Credit in Native Communities by economist Miriam Jorgenson.

2 For more on this, see the Federal Reserve’s Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on CRA modernization.

3 Based on a defined asset size, some smaller financial institutions can be exempted for portions of these activities.

4 “LMI” and “small businesses or farms” have clear parameters in the context of the CRA. See our 2018 article “Defining ‘low and moderate income’ and assessment areas” for more details on income. Small businesses and farms are defined by certain U.S. Small Business Administration standards, or may be farms or businesses with less than $1 million in gross annual revenue.

5 Analysis performed by Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis staff.

6 Other elements of the lending test include evaluating the percentage of the bank’s loans originated or purchased inside its assessment area versus outside.

7 Smaller banks may not be required to undergo a community development test. For more on how CRA exams differ depending on a bank’s size, see our 2018 article “Fair lending laws and the CRA: Complementary tools for increasing equitable access to credit.”

8 For more information on community development as defined by the CRA, see the Code of Federal Regulations.

9 Using the CRA Analytics Data Tables, we calculated the number of CRA-eligible loans per capita by county. The average CRA loan originations per person in counties where American Indians and Alaska Natives are 50 percent or more of the total population is about 0.071, compared to 0.085 in the rest of the counties in the 50 states and District of Columbia. Note that data on CRA-eligible lending activity may be limited by reporting requirements. Smaller banks are not required to report these data, but may choose to submit it.

10 In addition to suffering reputational harm, banks receiving low scores on their CRA examinations may be prohibited from opening new branches or merging with other financial institutions.

11 From 2015 to 2019, about 89 percent of evaluations resulted in a Satisfactory rating, while about 10 percent resulted in an Outstanding rating.

12 A more detailed discussion of performance contexts can be found in our 2019 article “Understanding the CRA performance context.”

13 The public can submit comments via the Federal Reserve’s website by finding a bank’s upcoming CRA examination.