In certain situations, working with entities that provide care and education for young children may help banks meet their Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) obligations. Yet the two sectors don’t always recognize this potential intersection: banks might overlook opportunities to facilitate an increased supply of early care and education (ECE), and ECE providers are often unaware that their needs could align with lenders’ CRA strategies. Making the connection depends on understanding how crucial ECE is to communities and how the CRA frames loans and other bank activities as community development.

The importance of ECE

The ECE sector comprises for-profit companies, nonprofit organizations, and government agencies. Providers can be home-based family child care programs, child care centers, public school-based or private preschool programs, or government-sponsored programs like Head Start and Early Head Start.

The sector plays an important role for primary caregivers and their young children, caregivers’ employers, and entire communities. For example, child care allows parents to enter and stay in the labor force. Recent studies reveal that an inadequate supply of child care costs families and businesses, reducing income and productivity while increasing employee turnover. For young children, high-quality ECE supports healthy development and prepares them to succeed in school and, eventually, the workforce. And society also benefits, from higher tax revenue and lower costs related to less use of remedial education and the criminal justice system, for example. Economists have calculated a high public return on investment for ECE programs, particularly those targeted to low- and moderate-income (LMI) families that may otherwise lack access to high-quality ECE opportunities.

Essentials of the CRA

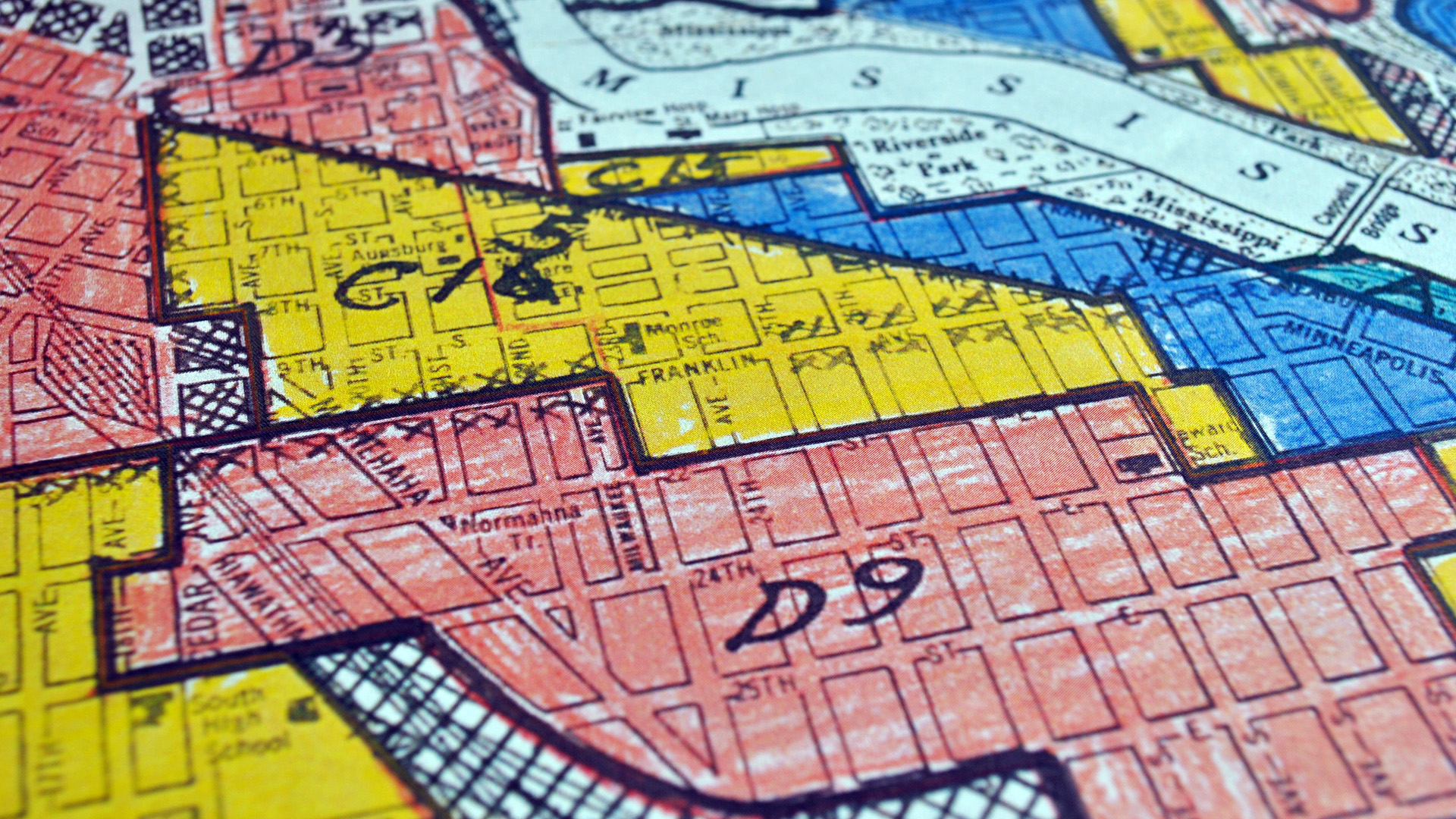

Enacted in 1977, the CRA encourages banks to help meet the credit needs of the communities in their geographic area, including LMI communities. The law creates a framework for assessing banks’ activities and investments supporting community development services like ECE for LMI families.1 The CRA tasks examiners from three federal financial regulatory agencies—the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency—with evaluating banks’ efforts in that regard. Congress created the CRA in reaction to practices like redlining. Redlining occurs when banks systemically underserve or unfairly treat residents in particular areas—often neighborhoods with a relatively large population of people of color.

CRA evaluations of banks, which typically take place every two to five years, are complex and differ based on banks’ asset sizes and other factors.2 However, geography always plays an important role in the CRA; banks are evaluated on activity within their assessment areas, which are primarily defined by the banks’ branch locations. Assessment areas may include LMI, underserved, and/or distressed geographies.3 Attention is given to banks’ efforts to serve and lend in those geographies.

Most evaluations include a lending test, which features an analysis of a bank’s efforts to meet the credit needs of small businesses, small farms, and households in its assessment areas. For larger banks, examiners also consider community development activities, such as investments, grants, and services, when evaluating the bank’s CRA performance. Community development is defined in regulations and includes, among other things, certain loans to small businesses and investments in community services targeted to LMI individuals. Bank employees’ involvement in activities that are defined as community development under the CRA regulations may also be considered if those activities relate to the provision of financial services.4

When evaluating a bank’s CRA performance, examiners take into account the performance context within which the bank operates. The performance context includes community information drawn from quantitative data and discussions with community representatives. Examiners also consider any comments received from the public about the bank’s CRA performance. Community development activities that are most responsive to the community needs indicated by the performance context generally receive greater weight in the analysis of a bank’s CRA performance.

Opportunities for loans, investments, and volunteerism

Banks can undertake many CRA-relevant activities in the context of the ECE sector. Bank loan amounts under $1 million to ECE providers in LMI geographies, and to ECE providers with revenues under $1 million, generally receive favorable CRA consideration. Loans over $1 million may also be eligible for CRA consideration in some cases. Banks may also have opportunities to earn CRA consideration for other affordable credit products extended to ECE providers.

However, according to industry experts, child care providers’ use of banks’ small business lending products is infrequent. (For more on this, see the article referenced in our “CDFIs and ECE” sidebar below.) This may result from the many financial challenges child care providers typically face. Market prices for ECE are often very close to the cost of providing care, so child care business models often have thin profit margins with few options for improvement. Many families can’t afford to pay higher tuition rates, and child care providers can’t reduce staff without compromising safety or quality. Government-funded subsidies for LMI families also often fall short of covering the costs of providing ECE. In addition, industry observers note that many ECE providers enter the field to follow their passion for working with children and may lack a foundational understanding of best practices for operating a business.

These conditions may all limit opportunities for banks to finance child care providers, and may also limit providers’ awareness about the best way to approach lenders. As a result, many child care businesses rely more on higher-cost credit cards or personal loans, which exacerbates all of the underlying issues, experts say.

However, lending money safely and profitably to child care businesses is possible. For example, some community development financial institutions (CDFIs) have specialized in child care financing. Successful models often include technical assistance to help child care providers navigate the financing process. This can include developing and implementing a business plan to help lenders understand a child care provider’s business model and potential for repaying loans.

Extending credit is not the only option for banks that are interested in incorporating the ECE sector into their CRA strategies. Investments in ECE, such as forgivable loans or grants, are also potentially eligible for CRA consideration if they meet the CRA’s definition of community development, which includes “Community services targeted to LMI individuals.” And under the right circumstances, investments in “community- or tribal-based” child care options may be an example of an activity that would receive consideration during a bank’s community development test, according to guidance issued by all three CRA regulators.5 Banks could also explore investments in revolving loan funds that focus on ECE, such as those operated by CDFIs.

Such investments may be critical in areas with struggling child care markets characterized by low supply. Lower-income and rural geographies are particularly likely to have lower supplies of high-quality child care relative to the potential demand.6 Data also suggest that LMI areas—and, in particular, LMI areas within communities of color—are likely to face the biggest supply constraints in a post-pandemic market.7

Bank staff can also invest their time and skills in efforts to support the child care industry. For example, nonprofits and foundations around the country have invested resources in improving the business skills of child care operators. Bank employees can also lend their financial expertise to support ECE providers—or the organizations that support those providers.

A key factor for the community development test for ECE activities may be the share of children served that qualify as LMI based on their families’ income. The geographic location of community development activities is also important. That is, banks that provide loans, investments, or services to ECE initiatives for which the majority of children served are from LMI families or are located in LMI, distressed, or underserved non-metropolitan middle-income areas, or designated disaster areas may receive CRA community development credit for these activities.

Whether banks are interested in lending, investing in community development activities, or volunteering to support the ECE sector in their assessment area(s), partnerships with local organizations and public agencies can help steer their efforts toward their most useful ends. For their part, ECE providers interested in sharing information about a bank’s CRA performance may submit comments via the three CRA regulators’ websites.8

ECE and CRA modernization

The Federal Reserve is in the process of updating its regulation on the CRA for the first time in about 25 years. The proposed rule aims to reflect changes in the banking industry and improve implementation of the CRA so that it better achieves its core purpose.

The Federal Reserve is soliciting feedback on the modernization effort in the form of a series of proposals and questions in the Federal Register. For example, ECE is relevant to questions about community services, economic development, revitalization and stabilization, and determining what community development activities qualify. Instructions for submitting comments about the proposed rule are posted on the Federal Reserve’s CRA home page. The deadline for submitting comments is February 16, 2021.

ECE providers, funders, and other stakeholders may find other areas within the CRA proposal relevant. Public comments play an important role in shaping a modernized CRA and achieving the law’s objectives: for all Americans to have access to credit, regardless of the size of their business, their household income, or where they live.

Endnotes

1 Investments in young children are not exclusive to the ECE sector. For example, programs that provide services for maternal and child health, early childhood mental health, early childhood screening, and child welfare can provide benefits to participants and society. From a CRA perspective, bank involvement in these types of early childhood development programs that serve LMI families may also qualify as eligible activities. While this article focuses on bank activities in the ECE sector, involvement in other types of early childhood development programs may also fall within the purview of the CRA.

2 Detailed information is available on the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System’s “CRA Evaluation Methods” web page.

3 The methodology for determining underserved and distressed status, and the 2020 list of such geographies, can be found via a June 2020 announcement from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, while the criteria for inclusion on the list can be found via the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. The criteria consider poverty rates, unemployment levels, population loss and density, and other factors.

4 The full definition of community development can be found at the Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. For more detail on employee participation in community development activities, see the 2016 “Interagency Questions and Answers Regarding Community Investment,” Section §__.12(i), in the Federal Register.

5 See the 2016 “Interagency Questions and Answers Regarding Community Investment.”

6 Rob Grunewald and Michael Jahr, Rating YoungStar, WPRI Report (renamed Badger Institute), June 2017.

7 Rasheed Malik, Katie Hamm, Won F. Lee, Elizabeth E. Davis, and Aaron Sojourner, The Coronavirus Will Make Child Care Deserts Worse and Exacerbate Inequality, Center for American Progress, June 2020.

8 For information on the regulators’ comment-submission processes, see their respective CRA examination-schedule web pages at Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.