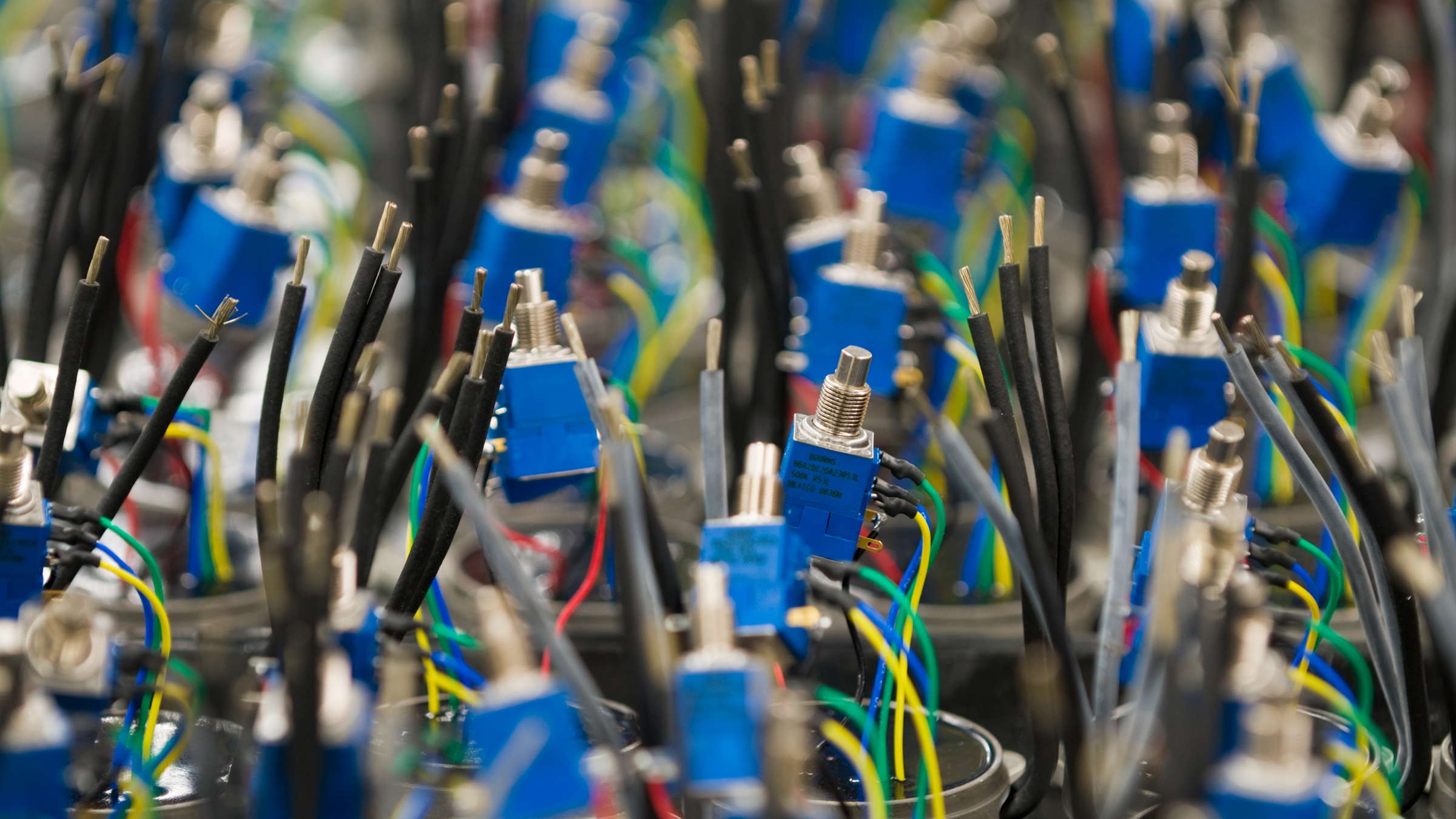

At the base of the Mission Mountains in northwestern Montana, a group of workers at the S & K Electronics warehouse hand-assembles electronic components smaller than a grain of salt. Once these pieces leave the warehouse, they become critical parts for massive and complex machinery like the F-35 aircraft and the M1 Abrams tank. Founded in 1985, S & K Electronics is one of several enterprises owned and operated by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) on the Flathead Indian Reservation, generating good, stable jobs for tribal members and nonmembers in the local community. The firm provides full benefits for employees and many opportunities for advancement and in-house training. S & K Electronics and other tribal enterprises owned by the CSKT employ nearly 1,200 people. Alongside the tribal government, CSKT tribal enterprises help make the tribe the reservation’s largest employer.

S & K Electronics is just one example of a tribal enterprise—defined as a business principally owned by an American Indian or Alaska Native tribe. The firm plays an integral role for the Salish and Kootenai community as a whole by returning a portion of its revenue as a dividend to the tribe to fund government services. In 2020, S & K Electronics generated around $1 million for the tribe, which helped fund departments ranging from forestry to health care to cultural services. Yet despite their successes, tribal enterprises like S & K Electronics have difficulty growing and diversifying, due to limited access to credit and investment.

A million jobs, billions in revenue

While tribal enterprises have their roots as far back as the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, a watershed moment for tribal business occurred in the wake of California v. Cabazon and the subsequent Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in the late 1980s. This Supreme Court decision and federal legislation, which dealt with affirming and regulating Indian gaming, created a new potential industry for tribes while also reaffirming their sovereignty.

Today, tribal enterprises are economic engines, locally and regionally. As of January 2020, tribes provided over 1.1 million jobs in the U.S. economy, the large majority of which were held by non-tribal members. Tribes are active participants in an array of industries, including hospitality, tourism, energy, technological manufacturing and development, and financial services. For example, in addition to S & K Electronics, the CSKT own gaming and energy enterprises, and a local bank. These tribal enterprises are integral parts of key regional and state economies and support non-tribal governmental coffers, collectively providing billions of dollars in local, state, and federal tax revenue.

Distinct challenges

Unlike their state and local government counterparts, tribes encounter numerous issues—including complex land tenure, limited tax bases, and dual taxation—that make the funding of public goods and services almost entirely reliant on either federal government appropriations or revenue that tribal enterprises generate.

This reality presents two distinct challenges. The first is that tribal enterprises are an unpredictable source of revenue for tribal governments, because they’re concentrated in volatile industries such as gaming, entertainment, and energy. Any economic shortfall that reduces tribal enterprise revenues affects the tribe as a whole, not just the businesses. Many tribal communities are facing this situation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since many tribal enterprises are in sectors such as gaming and entertainment that were disproportionately affected by social-distancing measures in 2020, losses were severe: a fall 2020 Center for Indian Country Development (CICD) survey found that over half of tribal enterprises reported revenue losses of more than 20 percent, and tribal governments consequently had to reduce both essential services and investments in infrastructure.

The second challenge is limited access to credit in tribal communities. Because a large portion of tribal enterprises’ generated revenue goes back to the tribal government, collateral is hard to come by. This makes securing a business loan difficult and limits the options of a tribal enterprise. A dearth of collateral can be a limiting factor for many tribes that are trying to grow and diversify their tribal enterprise portfolios. This vicious cycle further reinforces the substantial economic disparities in Indian Country brought about by chronic underfunding and generational disinvestment.

Addressing these challenges is varied and complex, and numerous other factors contribute to them. For example, developing a skilled workforce is essential for tribal enterprise growth and diversification. At the same time, CICD’s work surveying tribal entities suggests that one of the most direct ways to support tribal enterprises, and tribes, is to alleviate the credit needs of Indian Country.