One strain of the argument for a higher minimum wage centers on fairness. This can include a desire to redistribute income, or a basic belief that no one should earn a wage too low to afford the necessities of life.

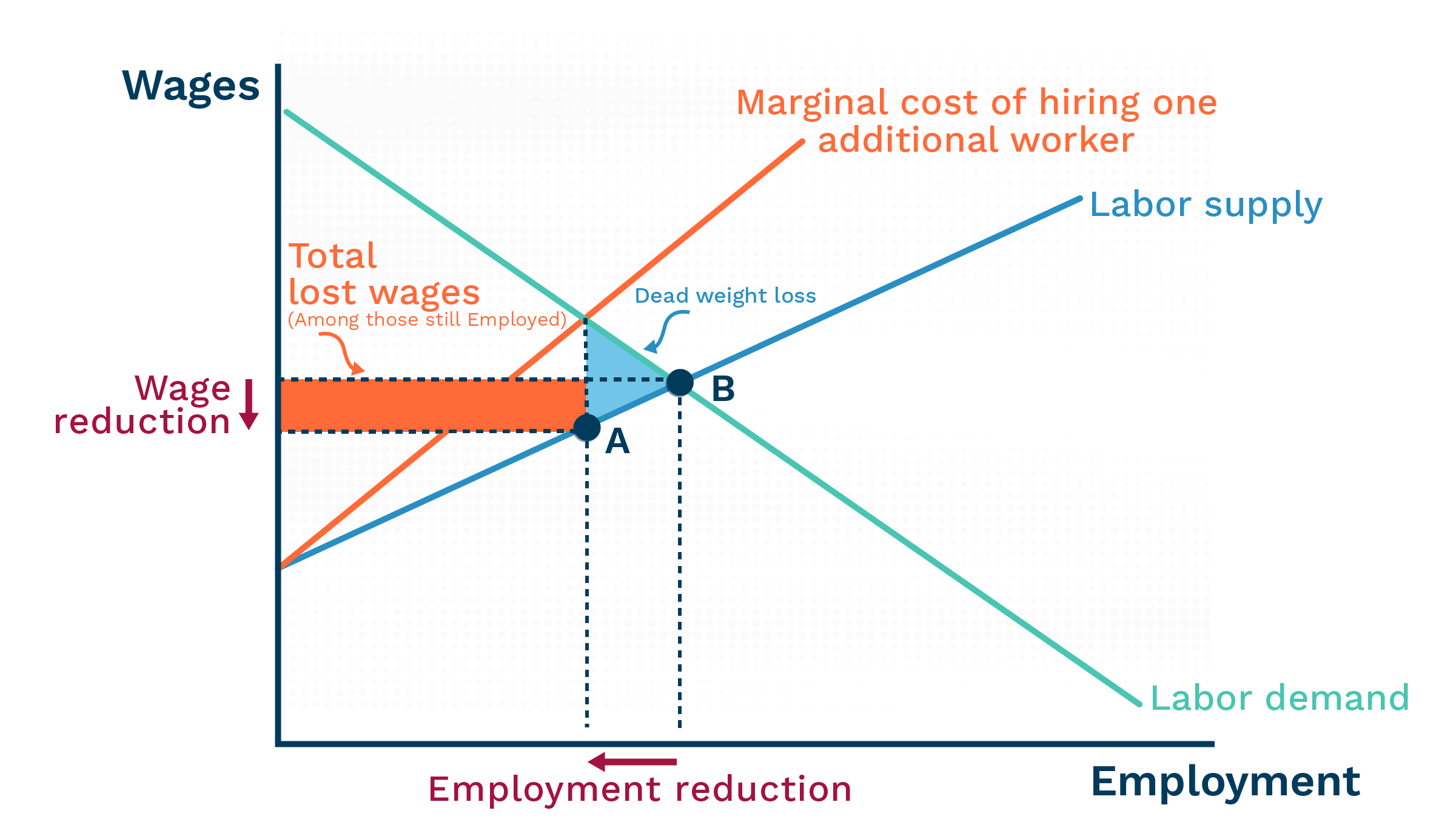

A second major argument is that the labor market is economically inefficient—that employers have some degree of market power, allowing them to pay workers less than they are worth by hiring fewer people. If raising the minimum wage made the labor market more competitive, the argument goes, business owners would sacrifice some profit. But wages, output, and employment would go up, and society overall would be better off (Figure 1).

There are many reasons to suspect the deck is stacked in favor of employers. Workers lack complete information about the jobs potentially available to them and what similar workers in the economy earn. It takes time and money to search for a job, not to mention physically moving for work. In any given city or field, the market for certain skills could be dominated by a few large companies that share wage information or otherwise retain power to set wage rates.

This labor market power costs American workers 25 percent of their potential earnings on average, according to a 2021 working paper from the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute (forthcoming in the American Economic Review).

Having made this case that labor markets are far from competitive, these same economists—Kyle Herkenhoff and Simon Mongey of the Minneapolis Fed and David Berger of Duke—turned their attention to a natural policy question: How much of the imbalance in labor market power could we address by raising the minimum wage? How much better off would that make us?

Their conclusion: Raising the minimum wage appears to make only a small dent in the labor market power of employers. To the extent that a minimum wage increases societal welfare, the benefit comes almost entirely from how a minimum wage redistributes income—a much more subjective question. The analysis is the subject of their new Institute Working Paper, “Minimum Wages, Efficiency and Welfare.”

“Once we strip these redistributive effects out, the efficiency gains are small,” said Mongey. “Efficiency arguments alone don’t seem to argue for substantially higher minimum wages above the current federal minimum wage.”

An old idea, but not necessarily a correct one

This finding goes to the heart of a recent report from the U.S. Department of the Treasury on The State of Labor Market Competition.

Citing the work of Berger, Herkenhoff, and Mongey, among others, the report concludes that “the American labor market is characterized by high levels of employer power,” resulting from “natural labor market frictions, employer concentration, and anti-competitive labor market practices. Employers exploit this market power by holding wages and certain non-wage benefits beneath their competitive level.”

In economic terms, American workers contend with the outcome of a “monopsony.” This is the condition when a consumer with market power—in this case a firm as a consumer of labor—profits from a noncompetitive outcome that harms society at-large. Raising the minimum wage, the report states, “is a straightforward approach to addressing lower wages under monopsony and can help increase employment.”

This is a classic “Microeconomics 101” idea with understandable appeal, said Mongey. However, when the economists subject this theory to scrutiny, it fails to deliver. They put it to the test using a complex model with firms of varying productivity (an “oligopsony” of multiple employers, rather than a literal monopsony), calibrated with extensive U.S. Census data.

The economists find that raising the minimum wage can bring small efficiency gains, up to a point. But this point is around $8, not much more than the current federal minimum wage of $7.25. What’s more, they write, the gains in efficiency “shift the economy only 2 percent of the way toward an economy with no labor market power.”

The optimal minimum wage would be a little higher in high-income regions—up to $10. Beyond this threshold, welfare gains from efficiency turn into losses as the higher wage reverses any initial gains in employment and job losses mount for less-educated workers (Figure 2). “The sign flips aggressively,” as Mongey puts it.

Pressuring the little guy

Given the economists’ previous determination that U.S. employers possess substantial market power, why doesn’t the minimum wage play out like the basic monopsony model would predict?

Mongey says the primary reason is that actual firms vary greatly in their productivity. Less productive firms tend to be smaller, and their lower productivity means they pay employees less.

“The first firms that get hit as you raise the minimum wage are the small guys in a market,” Mongey said. “Because they’re small, they’re competing tooth and nail for workers anyway. They don’t have a lot of market power that really needs correcting with a minimum wage.”

The firms with the most labor market power are—with some irony—the more productive firms that already pay workers more. A minimum wage will tend not to affect these firms until it has reached such a high level that it begins to cause more harm than good. In the meantime, the minimum wage increases costs on many smaller businesses that don’t employ that many people, on aggregate.

“A minimum wage goes from the bottom of the ladder, up,” said Mongey. “Really what you want from a policy to address market power in the labor market is something that is top-down.”

As a top-down example, consider recent decisions by “big guys” like Amazon and Target to pay all employees at least $15 an hour. While they might seem similar to a minimum wage hike, these corporate decisions—whether inspired by corporate altruism or public relations pressure—ripple out much differently than a minimum wage law that affects every workplace down to the mom-and-pop corner store.

Bringing fairness into focus

In deflating the market-efficiency argument, the economists do not intend to write off raising the minimum wage as a policy option.

“There are solid arguments for having minimum wages that are $12, $15, or $16 an hour,” Mongey said. “But when we’re arguing for those minimum wages, we have got to face the fact that we are making that argument on the basis of redistribution.”

There is no objectively “best” outcome for distributing income; this is a matter of ethics, values, and politics. As an example, however, the economists run their model with “utilitarian social weights”—a sophisticated way of saying that society seeks to achieve the greatest aggregate benefit, with each person weighted equally.1

The utilitarian experiment yields an optimal federal minimum wage of $15.12, uncannily close to the $15 wage that anchors many recent minimum wage campaigns and local laws. There is no inherent reason the model should yield something so close to this real-world number, Mongey said. Yet it did—and the result is thought-provoking.

More than one way to redistribute

This degree of redistribution—essentially moving money from the owners of businesses (including anyone holding stock in a public company) to those who work for them—would be a dramatic change in the United States. A higher minimum wage might get us there if we make that policy choice.

But a minimum wage also alters incentives on hiring and capital investment, and this new research shows just how carefully it must be calibrated to avoid tipping over into economic damage. Is raising the minimum wage the optimal option for redistributing income, given the availability of tax, subsidy, or other government policies to pursue the same goal?

Likewise, the conversation can continue about the right policies to address the wage-setting power of firms previously documented by Mongey and his co-authors. Although the minimum wage looks like a less promising approach, such labor market power still represents a welfare loss to the national economy. The recent U.S. Treasury report features other ideas to increase competition in the U.S. labor market, such as restricting the use of non-compete agreements, vigorous enforcement of antitrust laws, enhancing workers’ power to organize and collectively bargain, and reducing unwarranted occupational licensing requirements (the subject of a recent data analysis by the Minneapolis Fed).

Mongey believes that by highlighting the limited effects of the minimum wage to reduce labor market power, their new work brings the policy question into focus: “Once you understand that the gains from efficiency are small, then the argument should turn to: What is the best way to do redistribution?”

Endnote

1 A utilitarian approach would arguably be a much fairer outcome than the weights implied by actual U.S. data, which place a much heavier social value on the well-being of college-educated households.

This article is featured in the Fall 2022 issue of For All, the magazine of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute

Jeff Horwich is the senior economics writer for the Minneapolis Fed. He has been an economic journalist with public radio, commissioned examiner for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and director of policy and communications for the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. He received his master’s degree in applied economics from the University of Minnesota.