We live in an information-rich environment in which choices abound. What health care plan should I enroll in? What fund should I invest my retirement savings in? What school should I send my children to?

These are choices with fairly significant consequences. Sometimes institutions will make default assignments—your 401(k) will be invested in a target date mutual fund, say, if you make no other selection—but sometimes they do not. Whether a default exists and what that default should be is a rather profound philosophical choice, with profound influence over people’s choices.

“Leaving decisions open-ended puts them in the hands of individuals or families to make decisions based on their own values and priorities. That is perhaps very empowering,” said Institute visiting scholar Sarah Cohodes, an associate professor of economics and education at Teachers College, Columbia University. "On the other hand, not having a default might mean that people who don’t have the resources, the time, the energy, the ability to navigate the information, are at a disadvantage."

This situation is occurring more frequently in the realm of education with the rise of school choice. In much of the United States, students are assigned by default to their neighborhood public school. However, a growing number of school districts, including Boston, Denver, New Orleans, and New York City, have moved away from this default in favor of a system in which all families submit their preferences for schools to the district, which then uses an algorithm to match students to schools.

School choice is often adopted to increase access to high-performing schools. But it introduces a complex information environment that takes time and resources to navigate well—and time and resources aren’t distributed evenly across students and their families.

So Cohodes and co-authors Sean Corcoran, Jennifer Jennings, and Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj set out to study whether providing New York City eighth graders with customized information about high schools with high graduation rates would change students’ choices and, ultimately, where they went to high school.

“Part of our motivation is recognizing that not all families will be able to afford a $400 high school admissions consultant. We wanted to investigate what structures we can put in place to support families making these choices and to make access to the necessary information more equitable,” Cohodes said about her Institute Working Paper “When Do Informational Interventions Work? Experimental Evidence from New York City High School Choice.”

What the multidisciplinary team found is encouraging: When there was evidence that students and families engaged with the materials, the informational interventions succeeded in shifting students to apply to and enroll in schools with higher graduation rates. The impact was largest for English learners, demonstrating that interventions can be designed in a way to help historically disadvantaged groups.

However, Cohodes is quick to point out, this impact is the equivalent of a crutch—it helps you get around but doesn’t treat your broken leg. Reducing administrative burdens and making all schools good schools would benefit all students.

Choosing a high school in New York City

Across its five boroughs, New York City boasts more than 400 high schools that are home to more than 700 different programs. Some teach veterinary courses; others focus on the arts or college prep. These programs vary in the criteria they use to prioritize students: geographic area; school attendance record; standardized test scores; grades; auditions. The city’s 75,000 eighth graders must submit a ranked list of up to 12 high school programs from among these 700.

Choosing a high school in New York City is thus a complex situation to navigate—for anyone, and particularly for 13-year-olds. Interviews by the research team revealed that students and their families frequently misunderstood pieces of the process. For instance, many students applied to schools for which they did not meet the eligibility requirements, and many were unaware that some schools gave preference to students who attended a school fair or information session.

It’s no surprise some locals call the application system “the beast.”

Making decisions in such an information-rich environment comes with “frictions”—the obstacles that can stand in the way of someone making what they would view as the best decision for them if they had complete information. It takes time to learn about dozens of programs. It takes resources to access the information and travel to fairs and exams. Students need to know their grades or test scores if there are academic criteria. They need the critical thinking skills to understand the matching algorithm.

“Some students need a lot of support to complete all the necessary steps to meet the application criteria at different schools. In some cases, families are in a position to provide that support. And in some cases, families aren’t in a position to provide that support,” Cohodes said. “For students and families who are underserved, who have a difficult time accessing resources, simple interventions and outreach could make a very big difference.”

Intervening with information

Previous research in economics and psychology, pioneered by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, has provided strong evidence that “choice architecture”—what and how information about a choice is presented and structured—affects the decisions we make, even when we come into the situation with a particular preference. (This research won Kahneman a Nobel in economics; Tversky was recognized for his role but he had died six years earlier, and Nobels are not awarded posthumously.) This finding opened the door to a rich literature that seeks to better understand informational interventions, which Cohodes defines as “providing options and giving people the criteria to navigate those options and make their own choice.” What kinds of decisions can informational interventions affect? What circumstances make interventions successful? Do different interventions work better for different groups of people?

These are the questions Cohodes and her co-authors set out to answer in the context of high school choice because “where students go to high school matters for their longer-term trajectories,” the researchers write. There is evidence, for instance, that attending a better-quality school or a small high school boosts student achievement for certain groups of students. And data show that high school graduates earn higher wages than non-graduates, on average—and a high school diploma (or equivalent) is a prerequisite for attending post-secondary education and earning higher wages still.

Through previous research on school choice, Cohodes and her co-authors developed a partnership with New York City’s Department of Education (NYCDOE), which had turned to economists when school choice was first implemented for help designing its matching algorithm. This partnership helped Cohodes’ team design their intervention in a way that mimicked how the NYCDOE implements programs so the results would be a “real-world” test of their potential impact. Specifically, the NYCDOE disseminates material about the high school application through middle school counselors, and those counselors have autonomy to set their own curriculum.

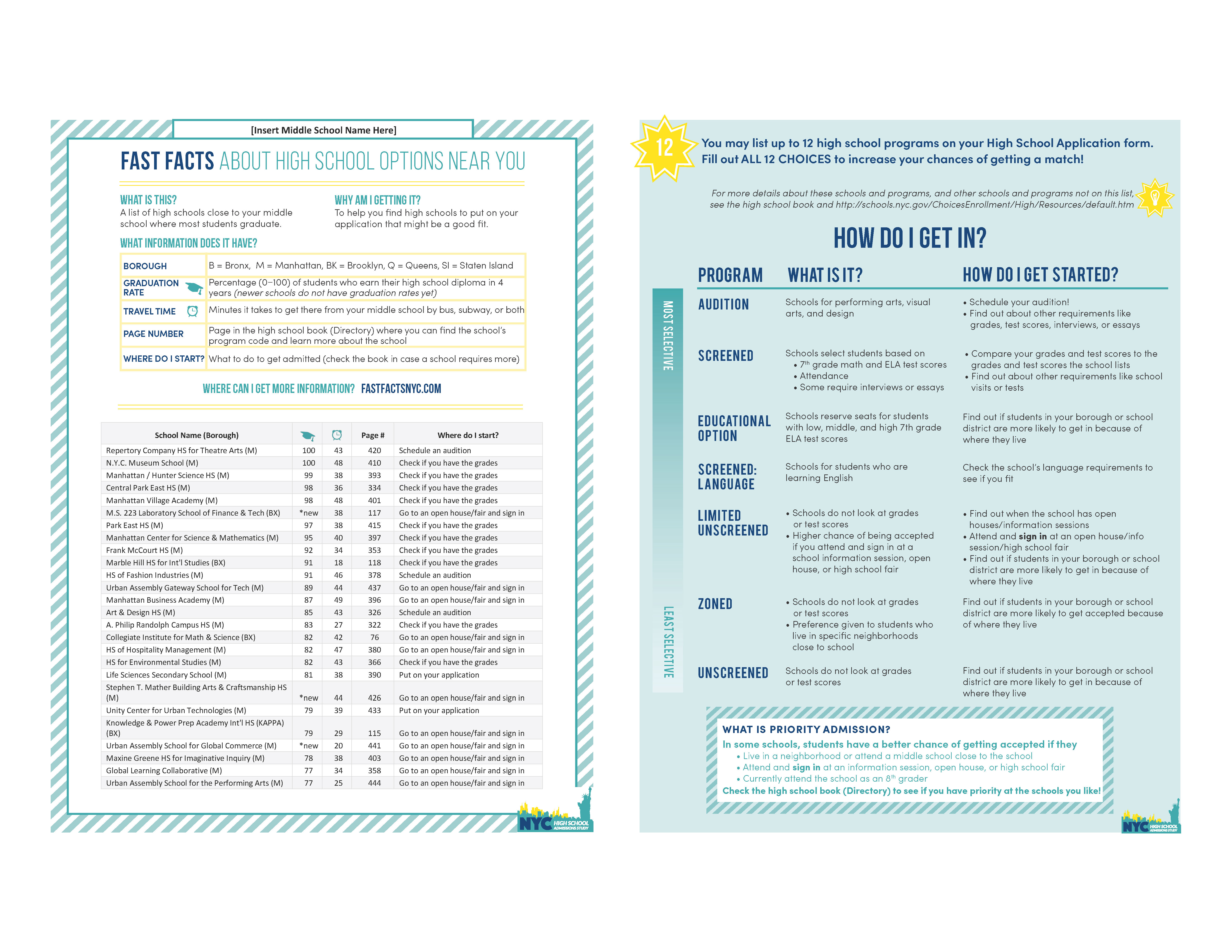

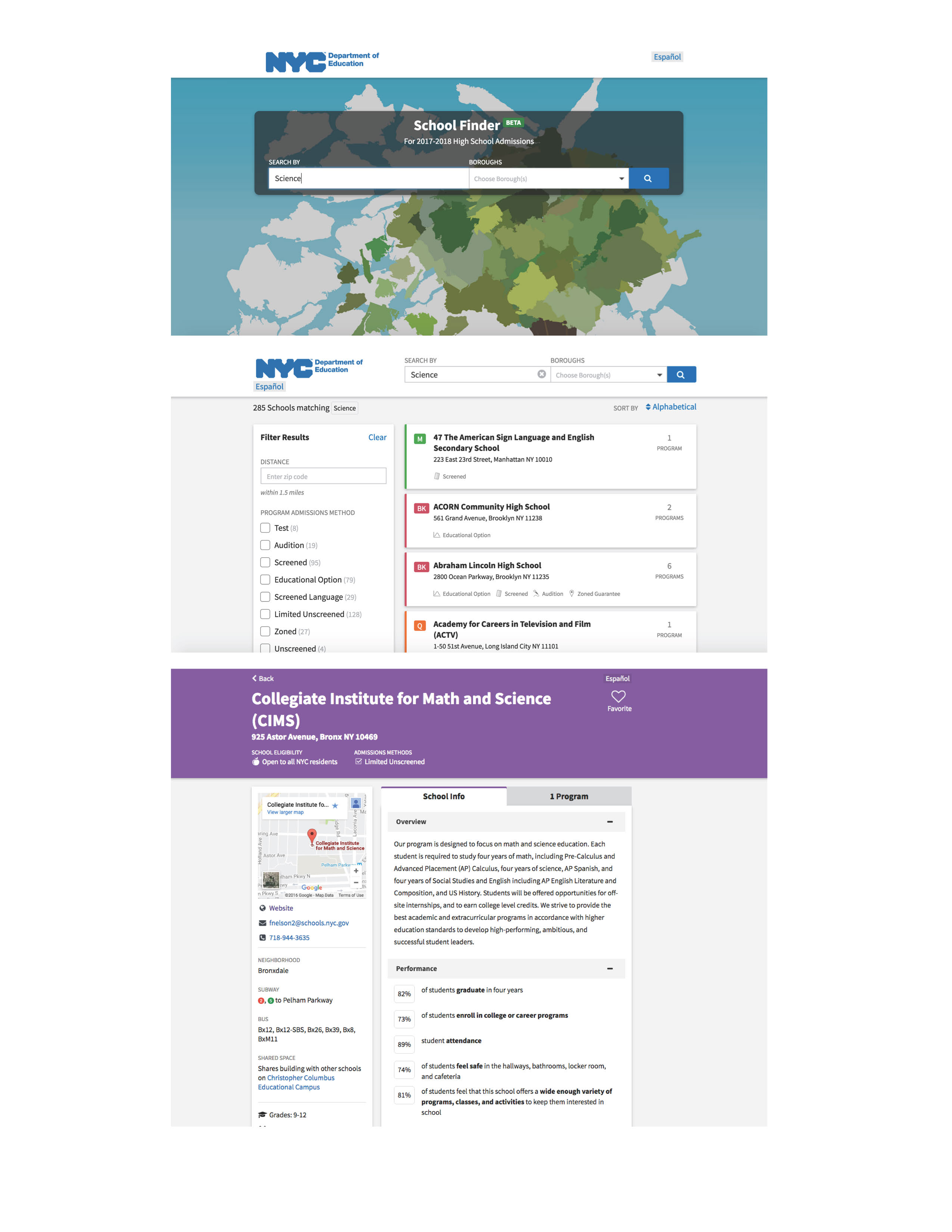

With that in mind, the authors designed interventions and supporting materials that they sent by mail to middle school counselors, not directly to students or their families. All students at a middle school were assigned the same intervention. These interventions—Fast Facts, the App, and School Finder—varied in delivery mode, the type of information, and the level of customization, described in Figure 1.

| Fast Facts | The App | School Finder | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery mode | Paper & online | Online | Online |

| Customization | Customized to middle school | Customized to student | Customized to student |

| Type of information | Specific recommendations | Specific recommendations | General information |

| Description | A list of 26 high schools with graduation rates above 75% selected based on proximity, graduation rate, and if past students at that middle school had a history of being placed at the high school. | A “virtual guidance counselor” that provides a customized list of high schools with graduation rates above 75% based on preferences inputted by the student. | A digital search tool of all NYC high schools, sortable only by distance and school name. |

| Samples | View document | View screenshots | View screenshots |

Limited but meaningful impact

To determine how the informational interventions impacted students, the study authors received access to NYCDOE administrative data on students’ high school choices, demographics, test scores, high school placement, and enrollment.

In interviews and surveys, about 85 percent of school counselors said they shared the materials they received with students or parents. Because the study authors do not know with certainty whether or not students actually used the materials, what they can study is the impact of assignment and access to an intervention.

Source: Sarah Cohodes, Sean P. Corcoran, Jennifer Jennings, and Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj, “When do Informational Interventions Work? Evidence from New York City High School Choice,” Institute Working Paper 57 (February 1, 2022).

Cohodes and her co-authors examine the interventions’ impact on several outcomes in the high school choice process—the graduation rate of students’ top school choices, the likelihood they would be admitted to the high-graduation-rate schools they selected, and the graduation rate of the school students end up enrolling at. Across these outcomes, Fast Facts paper flyer, the App, and School Finder had a limited but meaningful impact compared to the control group, while Fast Facts digital had no effect. For instance, 38.9 percent of students in the control group enrolled at a high school with a graduation rate below 75 percent. For students in the Fast Facts paper and the App interventions, that falls by 6 percentage points; for students in School Finder, it falls by 5 percentage points. (See Figure 2 for more results.)

Because the research team wanted to know if the interventions have different impacts on different students, they used their demographic data to dive into the results more deeply, with interesting findings. All of the treatments are particularly effective for English learners (defined by the authors as students receiving services to support learning English in the eighth grade, who make up 12 percent of students in NYC). For instance, Fast Facts paper, the App, and School Finder all reduce the likelihood of enrolling in a high school with a low graduation rate by 11 to 12 percentage points for English learners, almost twice the average effect on all students. This points “to the need for targeted help and materials in home languages for families navigating both the school choice process and an unfamiliar language,” the research team writes.

In general, the Fast Facts paper and School Finder interventions tended to benefit groups of students who have historically been underserved, including Hispanic/Latino students and English learners. The App, meanwhile, benefited historically advantaged groups more. This suggests that the design of the intervention may impact which students are reached—not all interventions reach all students equally.

Importantly, the evidence so far shows that students impacted by the interventions are not worse off for attending higher-performing schools: They don’t have worse grades and they haven’t failed more classes than their peers. Cohodes and the study team are continuing to follow these students to evaluate the impact on their graduation rates.

Engagement, trust, and systemic change

The analysis points to several insights for administrators of districts with school choice. First and foremost, “If you build it, they won’t necessarily come,” as Cohodes put it. Informational interventions will do little if they don’t generate engagement with the material. The one intervention that seemed to be used the least, the digital version of Fact Facts, also had little to no impact on student choices. “The point is maybe not so much exactly which schools we recommended, but rather that we got school counselors and students to engage with the process,” Cohodes reflected, through a suite of supporting materials: video, lesson plans, instructional material for discussing the tool, and practice applications.

Trust in the system is also important—and currently, it’s lacking. Qualitative work by the research team showed that there was a wide-spread belief among both students and school counselors that the matching algorithm used by NYCDOE was not fair, which turns it into “an opaque, nefarious thing in the background,” Cohodes said. “I know that if [a district uses] a centralized admissions algorithm, then the matching system is incredibly fair. But it’s not perceived as fair.” This lack of trust can have consequences if students feel they shouldn’t bother applying to more selective schools because they have zero chance of getting in.

Finally, information is not the only barrier in education. “My takeaway is that systems that involve administrative barriers are always going to be hard to navigate,” Cohodes said. “Rather than teaching people how to navigate them, maybe we would be better off reducing the barriers themselves.” The interventions she studies do lead some students to attend a high school they wouldn’t have otherwise, but the effects are not huge. More drastic improvements to student outcomes would require systemic changes. That includes investing sufficient resources in education so that all students attend schools that set them up for success.

This article is featured in the Fall 2022 issue of For All, the magazine of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute

Lisa Camner McKay is a senior writer with the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute at the Minneapolis Fed. In this role, she creates content for diverse audiences in support of the Institute’s policy and research work.