There’s no such thing as a good disaster. But as disasters go, floods are often particularly nasty for the destruction and soggy mess they leave behind.

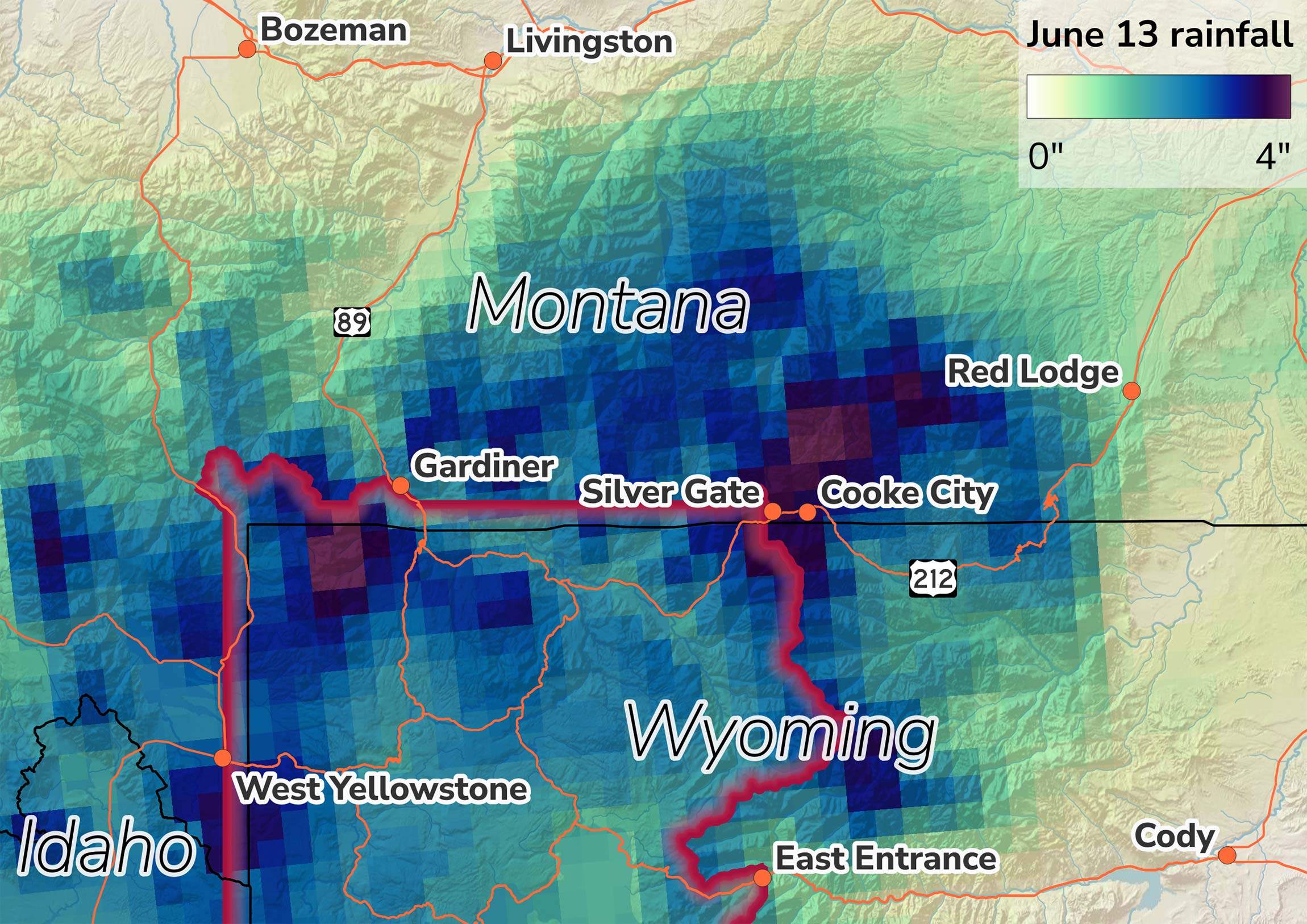

In mid-June, heavy rain and rapid snowmelt in and around Yellowstone National Park led to historic flooding in the park and across southern Montana. It tore whole houses from their foundation and floated them downstream like it was a new concept in vacation homes. In Red Lodge and other communities, overflowed streams poured into basements like teenage kids and left behind an even worse mess (Figure 1).

But this flood was more notable not for what it left behind, but for what it took with it once the water receded: all the tourists.

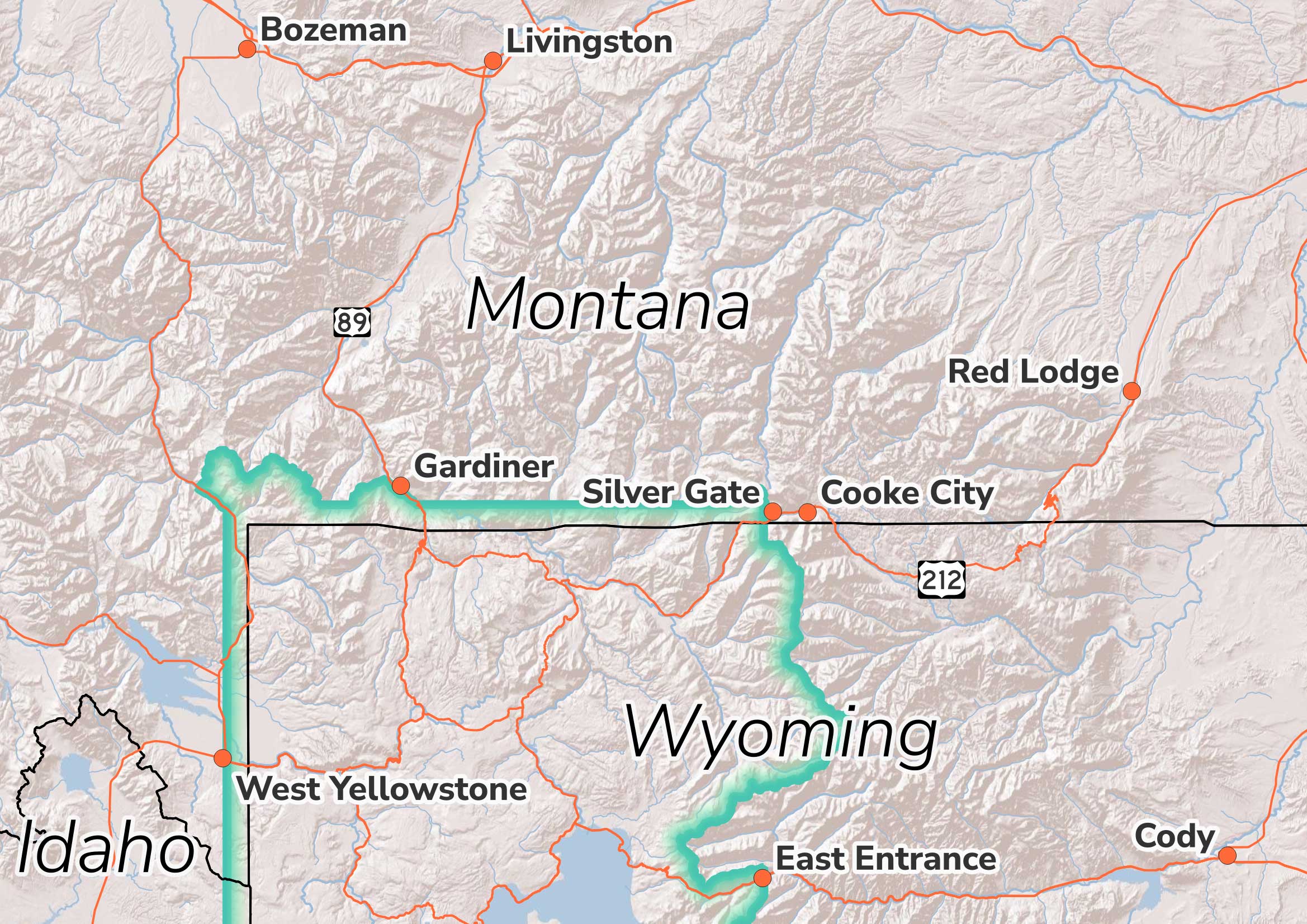

The flood was furious enough to close Yellowstone temporarily. Three entrances to the south and west (two in Wyoming and one at West Yellowstone, Montana) were reopened within about a week. But road damage was severe enough to indefinitely close Yellowstone’s entrances to the north (outside Gardiner, Montana, and the second largest entrance by volume) and the northeast (outside Cooke City–Silver Gate, Montana; see Figure 2).

In doing so, the flood cut the main artery to the heart of the tourism economy in southern Montana. Without access to Yellowstone, tourists flowed out of communities that had spent the winter preparing for record crowds. The owner of two hotels in Gardiner said it closed both facilities and laid off their staff after mass cancellations, because they “do not expect any revenue until a new road can be built (for Yellowstone access), giving tourists a reason to come to town.”

To assess flood damage, the Minneapolis Fed held large business roundtables in Gardiner and Red Lodge in late June and conducted an electronic survey of businesses across southern Montana through the first week of July. All comments provided were considered confidential to encourage engagement, and all comments in this article are anonymous, except when permission was explicitly granted.

Flood aftermath

This flood definitely left some physical scars. Fast-moving rivers and streams coming out of the mountains carved new paths, taking with them roads, bridges, and a handful of houses.

An estimated 100 to 125 homes were damaged across the region, though reports vary. Early estimates for damage to Montana roads and bridges have been ballparked at $30 million. Businesses were also damaged, including the Yodeler Motel and others in Red Lodge when the normally docile Rock Creek ballooned to historic levels and into downtown.

But the most damaging element of this flood, by far, was the immediate effect it had on tourists. Some 10,000 people were evacuated from the park in mid-June, representing the front edge of a reverse-deluge of present and future tourists from the region.

It’s hard to overstate the impact that Yellowstone National Park has on the southern Montana economy. Yellowstone is a singular draw that has enabled commerce to develop over time in otherwise remote communities.

A resort owner near Emigrant, Montana, likened Yellowstone to a major anchor tenant in a mall for its power to bring traffic to all other businesses. In southern Montana, other businesses and attractions—whitewater rafting, fishing guides, restaurants, and boutiques—exist to enrich and fill out the travel experience. But none can sustainably draw tourists on their own. “It’s not a destination anymore without the park. There are lots of other businesses. But it’s all about Yellowstone.”

In mid-June, tourists packed up their binoculars and sense of adventure and left town, and businesses saw a subsequent rush of cancellations from future visitors. A Minneapolis Fed survey of businesses in the region found that the loss of customers was—by far—the biggest concern regarding recovery from the flood (Figure 3). Slightly more than half of respondents expect to see their summer income cut in half compared with last year.

A restaurant in Fishtail, Montana, shared, “It’s been devastating. Total loss of income and workforce. We may never recover.”

Conditions are even worse in Park County, home to both of the closed entrances and to the heavily impacted communities of Gardiner, Cooke City, and Silver Gate that lie just outside the park. Here, more than seven of 10 survey respondents said they will see their revenue cut in half, or worse. The survey didn’t ask about losses larger than 50 percent, and many Park County businesses voluntarily cited losses of 80 percent, 90 percent, even 100 percent.

A food purveyor in Gardiner estimates that “99 percent of visitors to Gardiner come to see the park. Gardiner will be a ghost town in one year if the road [to the park] isn’t open.”

The owner of a small motel in Gardiner said that its revenue was “wiped out immediately as a result of an endless cancellation of bookings” from mid-June through September. The motel hasn’t had any revenue since June 14, yet expenses continue for payroll, utilities, and loan repayment. “We feel stuck and fear that we'll have to shut down our business soon if we are unable to get funding help to pay for these expenses.”

Road closures have turned Cooke City and Silver Gate into a functional dead end from a travel standpoint until the northeast access to Yellowstone is reopened, which is not expected until at least fall or early winter. By then, said a Cooke City resort owner, “the tourist season will be over. I have lost nearly all of my reservations for the summer, and there is literally no traffic. There is no reason to believe this will change any time in the future, which leaves us businesses wondering how we will meet our obligations. We need help.”

The timing of the flood almost could not have been worse. Tourism businesses in the region—which is to say, most of them—typically make 60 to 80 percent of their annual revenue during the summer season (including September), which is enough to pull many through slow winter months.

By mid-June when the floods hit, activity was approaching peak for many businesses. The park closure will likely remain in effect through the heart of the summer. Even under optimistic estimates, entrances will open with only limited capacity possibly later this summer or in the fall.

A restaurant owner in Gardiner said, “We are going to be more than 80 to 90 percent down … and [lower summer revenue] will not be able to sustain us through the winter if not immediately corrected. Summer allows sustainability through the winter months.”

Still more problems

Many businesses face major, compounding problems. For example, businesses were expecting a big year in tourist traffic this summer, and as a result, many made new investments in equipment, facilities, and other improvements to meet that demand. Many also bulked up on inventory to feed, clothe, and entertain all those tourists.

Many businesses that require reservations—whether accommodations or guided experiences—also require partial or full payment in advance. Now those businesses are faced with massive repayments, often with little or no savings, or any cash flow from daily operations. A restaurant and boutique hotel in Gardiner said she is facing $300,000 in refund requests, which she doesn’t have. “It’s not manageable.” Several businesses reported threats of legal action over refunds.

Not only are patrons canceling, but the spigot of new bookings has shut off almost completely. A rafting and outdoor entertainment company in Gardiner said it “had to refund hundreds of thousands of dollars over the past two weeks” and has missed out on hundreds of thousands in additional revenue because it has seen no new bookings. “We had negative revenue in June and expect July and August to be dismal.”

A hotel owner in Red Lodge said that cancellations as of late June were worth more than $600,000 in revenue “that will not be coming into this community.” She added that over the last two weeks of June, she typically would have seen 75 to 85 new bookings. They got six.

And despite a strong tourism economy of late, many businesses in the region are dealing with multiple years of volatility. In Red Lodge, for example, in 2020 traffic was reduced early in the season because of COVID-19, last year featured a major 40,000-acre fire that could be seen from town, and now, the flood.

What now?

The necessary road repair for both the north and northeastern entrances lies inside the park. Officials there have reportedly been good about communicating progress toward reopening but careful not to overpromise. They are also working with commercial guides and outfitters in Gardiner and Cooke City–Silver Gate to provide limited access to guided group travelers. While useful, this action would provide only a fraction of access that fully rebuilt roads would offer, and those will not arrive this summer.

Businesses in Red Lodge got some good news when the iconic Beartooth Highway (U.S. Highway 212) was reopened on a limited basis. Though it doesn’t provide direct park access and is only open seasonally, the Beartooth Highway is widely used by road-faring enthusiasts and is expected to bring some travelers back.

But businesses and communities across southern Montana continue to play an anxious waiting game. Many have turned their attention to two areas: assistance and marketing. Neither is likely to offer a quick fix.

A federal disaster was declared for Carbon, Park, and Stillwater counties, and the state has received some money for infrastructure repair to reopen access to Yellowstone. However, the region is unlikely to get much assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which provides aid for flood disasters. Most residential flooding was in basements; FEMA payments to homeowners is capped at about $38,000, and there’s a fairly high bar to clear to receive this assistance. Most businesses were not damaged to a degree that interfered with operations. And FEMA has nothing to offer those whose disaster consists of fleeing tourists and canceled reservations.

Businesses are in desparate need of operational and cash flow assistance given the flush of visitor cancellations. The state of Montana has a $5 million grant program for operational assistance, capped at $25,000 per business. Most say the total amount is far too little and the individual grant too small to help any but the smallest businesses. To date, there are no other obvious sources for this type of assistance, though some have pointed out that the state is still sitting on $93 million in funding from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

New loan programs are likely to have few takers unless they offer particularly generous terms. Dozens of businesses said they simply can’t take on more loans to get through the season because they already have loans they can’t pay, given little or no daily income.

Some attention is now focused on marketing. Many businesses pointed out there is an outside perception that the region is closed for business. The flood was a major story for the national media. Many showed helicopter rescues of campers and footage of a now-iconic home for park employees falling into and then floating down the Yellowstone River. Some communities faced cleanup and other hardships like disrupted sewer and water service and water-boil orders that sent a negative signal to travelers, and those impressions are hard to dislodge among outsiders.

Many businesses hope their geographic neighbors in Wyoming and other parts of Montana will help fill the visitor void. Several contacts noted that many Montanans wait until after the traditional summer season—once the crowd of outsiders leave—to enjoy the region.

Along these lines, formal plans are afoot among regional chambers of commerce and economic development agencies to start a broader marketing campaign to let people know that communities normally overrun with summer tourists have immediate openings available, everywhere, for everything. No reservation needed.

The marketing goal is simple, said Terese Petcoff, head of the Gardiner Chamber of Commerce: Let people know that communities across southern Montana—Livingston, Paradise Valley, Gardiner, and Cooke City—are “open, and we are ready for your business. … There has never been a better time to experience the hospitality—and the heart—of these eclectic mountain communities.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.