Before the pandemic, workers used to come in by the dozens each week to Jill Berg’s staffing and recruitment agency in Fargo, N.D. Now, she said, she’s lucky if she gets 10.

The labor market has shifted dramatically in North Dakota, eastern South Dakota, and west-central Minnesota, where her Spherion Staffing franchise has offices.

“Every position is extremely challenging,” Berg said. Recruiting permanent workers with higher skill sets, such as accountants and middle managers, was difficult before the COVID-19 pandemic and remains that way, she said. But now getting temporary workers is difficult, too, she said.

“If pay is below $20 an hour, it’s near impossible, especially in Fargo and Sioux Falls [S.D.],” she said.

State officials in North and South Dakota, as well as Montana, have said that one of the major causes of this tight labor market is the expanded jobless benefits offered by the federal government starting in early 2020 and continuing into September 2021. They argued that the benefits were too generous and too easy to collect, giving workers few incentives to get back to work.

Seven months ago, these states joined two dozen other states around the country in terminating the expanded benefits early with the expectation that employment would increase.

So far, it’s difficult to see what effect that has had. For example, when North Dakota terminated its expanded benefits mid-June, there were 7,200 jobless claims paid by various federal pandemic programs. As of November, the number of employed persons has increased by just 2,100. That suggests the expanded benefits aren’t the only explanation for the hiring difficulties businesses face and may be less important than other factors.

The labor market in North Dakota and other Ninth District states was already tight before COVID-19, but the pandemic has made the market even tighter and more complex with businesses and workers facing a multitude of challenges, labor experts told the Minneapolis Fed. Workers are retiring earlier than planned, shrinking the labor force. Jobseekers with young children are stymied by the shortage of affordable child care. The pandemic itself has increased labor mobility for some workers whether by converting office jobs into remote jobs, which may force employers in states with lower wages to compete with employers in higher-wage states, or by making relocation much more lucrative.

For example, hospitals in North Dakota are struggling to hire nurses, in part, because so many have left to be traveling nurses in COVID-19 hot spots around the country where their pay can be significantly higher, according to Kurt Schley, president of CHI St. Alexius in Bismarck, N.D. When St. Alexius itself had to hire traveling nurses, it had to pay them nearly five times as much per hour as staff nurses.

What happened when benefits ended

The expanded benefits comprised three programs – Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation, and Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation – which helped workers who traditionally don’t qualify for benefits (such as gig workers), extended the duration of benefits, and paid an extra $300 a week in benefits by the end of the program, respectively.

North Dakota ended its participation on June 19, 2021. Data show there was no sudden change in employment in the months that followed. In fact, employment had been trending upward since February and continued that trajectory into November (Chart 1). At the same time, the number of jobless claims that were being paid – “continued claims” in the jargon of unemployment insurance – had already been falling since January. In other words, the employment trends that preceded the termination of pandemic jobless benefits continued afterwards.

Similar patterns were found in Montana and South Dakota, which ended their participation June 27.

The other Ninth District states – Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan – ended theirs Sept. 4.

The Minneapolis Fed interviewed or surveyed labor market experts in all three Ninth District states that ended pandemic benefits early, and most said they didn’t think the policy made much of a difference in the labor market.

Melodee Lane, director of South Dakota’s Labor Market Information Center, said ending the pandemic benefits early probably didn’t have a huge impact there because state government didn’t impose a stay-at-home order that would’ve resulted in more layoffs.

South Dakota wasn’t paying pandemic benefits to very many jobless workers anyway. In the week before these programs ended, the state paid 1,400 continued claims, which amounted to 9 percent of all unemployed persons in the state. For comparison, that ratio was 40 percent in North Dakota and 71 percent in Montana.

In Montana, an employee of the state Workforce Services Division surveyed by the Minneapolis Fed in August said, “Now that the extra compensation for unemployment has ended (and the work search requirement has been reinstated), we are still not seeing seekers returning to the job search, and employers are desperate for employees.”

More jobs than workers

Cutting expanded benefits is essentially an attempt to pressure unemployed people to seriously look for work, assuming they aren’t already. Many state and business officials, as well as some job-service providers surveyed, have stories of workers who seem to just go through the motions of looking simply to meet state requirements for receiving benefits.

But that population alone is unlikely to meet the demand for labor because there just aren’t that many unemployed people to begin with, whether they’re serious about finding work or not.

The unemployment rate among Ninth District states in November ranged from 3.3 percent in Minnesota on the high end to 2.7 percent in South Dakota on the low end (Michigan, most of which is outside the Ninth, is excluded). These are historically low rates and lower than before the pandemic.

But these rates, low as they are, do not reveal the full challenge of matching workers with employers in such a tight labor market.

For example, a significant number of job seekers lack the basic qualifications for the jobs available, according to the Montana Workforce Services survey and a separate survey of nonprofit job-service groups in Minnesota conducted by the Minneapolis Fed in October. Between a third and a half of respondents in the surveys said job seekers they worked with were significantly or extremely challenged by lack of education, experience, interview skills, and references.

Survey respondents also said job seekers were very frustrated with automated systems employers use to weed out applicants, which seem to be relics from a time when job seekers were much more plentiful. In addition to requiring computer skills that not all workers have, these systems often require applicants to fill out lengthy forms with information already in their resume, a process repeated for every job.

“They usually spend a lot of time and frustration trying to apply online, and then they never hear anything from the employer,” one Montana respondent said. “A good share of the time they are never even totally sure if the application reached the employer.”

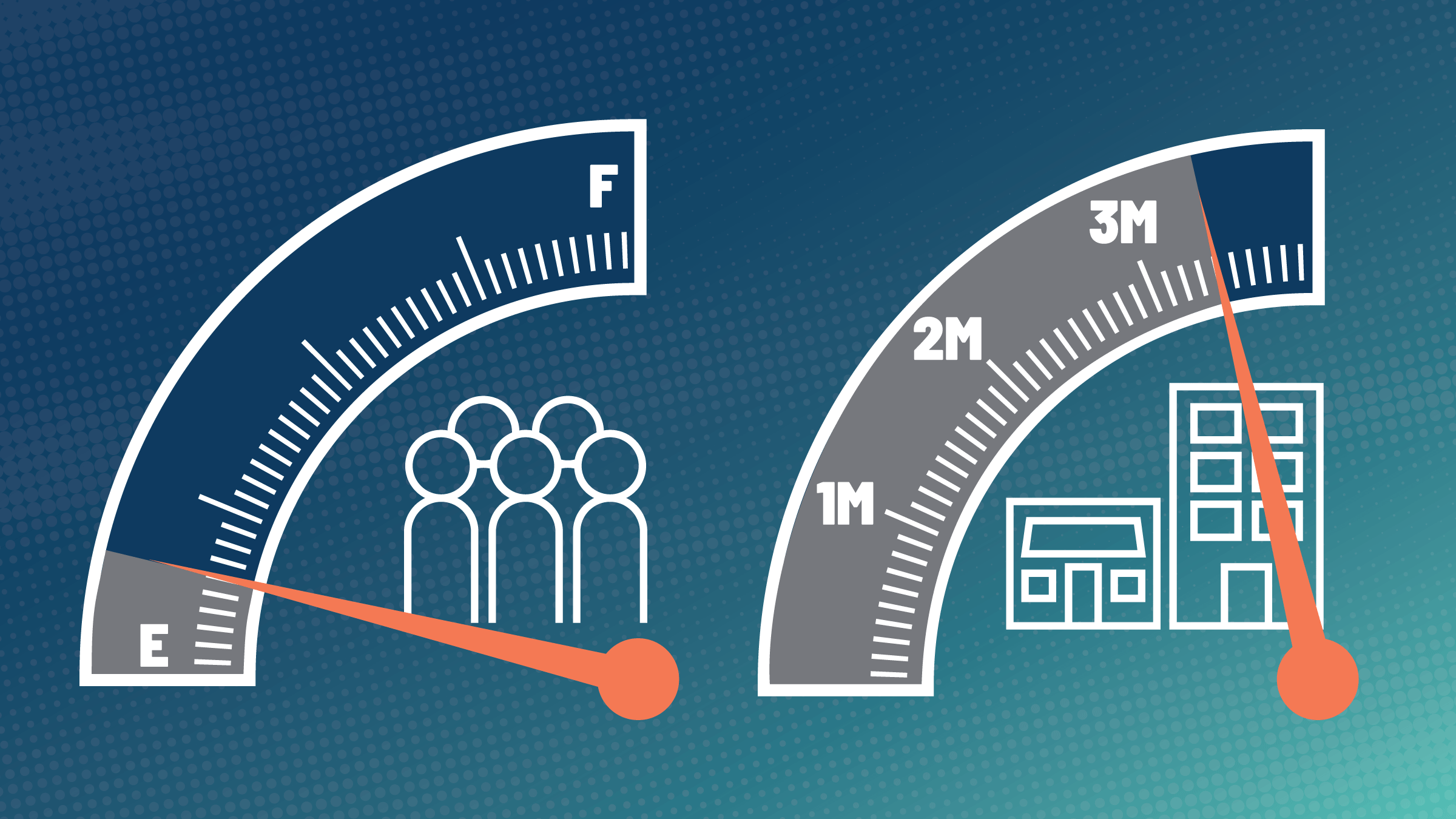

By some measures, the gap between the number of jobs (labor demand) and the number of workers (labor supply) is widening (Chart 2). The number of jobs – defined here as job openings plus employed persons – has been rising since fall 2020, but the labor force has risen much more slowly or has even shrunk. This labor force, as defined in government labor statistics, includes people with jobs and people without jobs who are looking, even those who might not seem very serious about looking.

This suggests that the labor market will remain tight unless more people who aren’t in the labor force decide to get back in. These are people who don’t have jobs and aren’t looking. Since around 2000, their numbers have grown faster than the number of people in the labor force, a trend that accelerated during the early part of the pandemic. As a result, the labor force participation rate, which is the percentage of the working-age population that’s in the labor force, has been in decline (Chart 3). Experts have cited a variety of reasons, from fewer teenagers getting jobs, to more workers reaching retirement age, to an increased use of painkillers by workers.

Outside the labor force

There are few sources of data at the state level that explain why participation has fallen so much during the pandemic, according to Marcia Havens, who manages the North Dakota Labor Market Information Center. But she has some theories based on what her staff and economic development officials have heard.

The lack of affordable child care has forced many parents in two-parent households to drop out of the labor force to care for children, she said. For some, child care costs now exceed wages, she said.

Many child care providers suffered earlier in the pandemic as parents laid off or working from home kept their children at home. With demand for child care rising again, providers face the same challenges looking for workers as other employers.

“Most daycares now have waiting lists of up to six months,” one Montana official said in a survey. “A parent cannot take a job if they cannot get reliable child care in a timely manner.”

More than three-quarters of respondents in that survey identified affordable child care as significant or extreme challenges for job seekers, second only to housing. A similar share of respondents in the Minnesota survey said the same thing, except in Minnesota child care was seen as a bigger challenge than housing.

In addition, many older workers have decided to retire earlier than planned, according to Havens and Lane, the South Dakota labor market expert.

Retirement is a major factor affecting labor force participation throughout the Ninth District, they and other experts said. Some older workers found working from home or being laid off – and presumably receiving jobless benefits – to be relatively pleasant, causing them to accelerate retirement plans; this could explain why some people who received pandemic benefits didn’t return to the labor force after those benefits ended.

It's possible, too, that some older workers who had been laid off felt they had little choice but to retire because they were unable to get jobs similar to what they had before.

“Older workers (55+) report experiencing age discrimination, such as being asked if they are aware of the newest technologies, about their plans to retire, their ability to work under pressure, leading the program participants to believe that they are being perceived as out of date and unable to learn and adapt,” a Minnesota job-service provider said in a survey.

A shift in bargaining power

In response to the tight labor market, employers are trying several different tactics to see what works.

Schley, the Bismarck hospital executive, likened it to putting out a lot of fishing lines in hopes that a few will catch fish.

Wages are going up rapidly in all Ninth District states, according to U.S. Department of Labor data. Employers are offering signing bonuses, retention bonuses, flexible scheduling, and training. Some businesses are even discussing ways to offer affordable child care, for example, through a community-based nonprofit model.

Workers’ expectations are also changing based on their experience in the pandemic, according to labor experts, whether it’s a preference for remote work, which many found offers a better work-life balance, or just wanting more out of a job.

One respondent to the Minnesota survey said the pandemic jobless benefits, which provided a higher income for some low-wage workers than their previous jobs, have motivated those workers to look for better jobs. “They are more driven to find employment with pay that allows them to live and make ends meet post-benefits. They say [knowing] what a decent income can feel like, they do not want to go back.”

Before the pandemic, low-wage earners, who traditionally had less bargaining power, as well as other workers had been making real gains in wages and employment levels as the labor market tightened. That may now be happening again as the economy recovers.

"It’s a very competitive environment right now,” said Arik Spencer, president and CEO of the Greater North Dakota Chamber. “Workers have the upper hand in trying to negotiate salaries, benefits, and things like that.”

Tu-Uyen Tran is the senior writer in the Minneapolis Fed’s Public Affairs department. He specializes in deeply reported, data-driven articles. Before joining the Bank in 2018, Tu-Uyen was an editor and reporter in Fargo, Grand Forks, and Seattle.