A pink slip. A plant closure. Then what?

Decades of economic research have shown that “displaced workers” affected by mass layoffs face a steep climb back to stable jobs and healthy earnings. Starting again at the bottom of the job ladder takes energy to seek out new opportunities and time to apply for them, and carries the risk that the next job may not be as good as the last. This process is slow, it is painful, and the scars can last for decades.

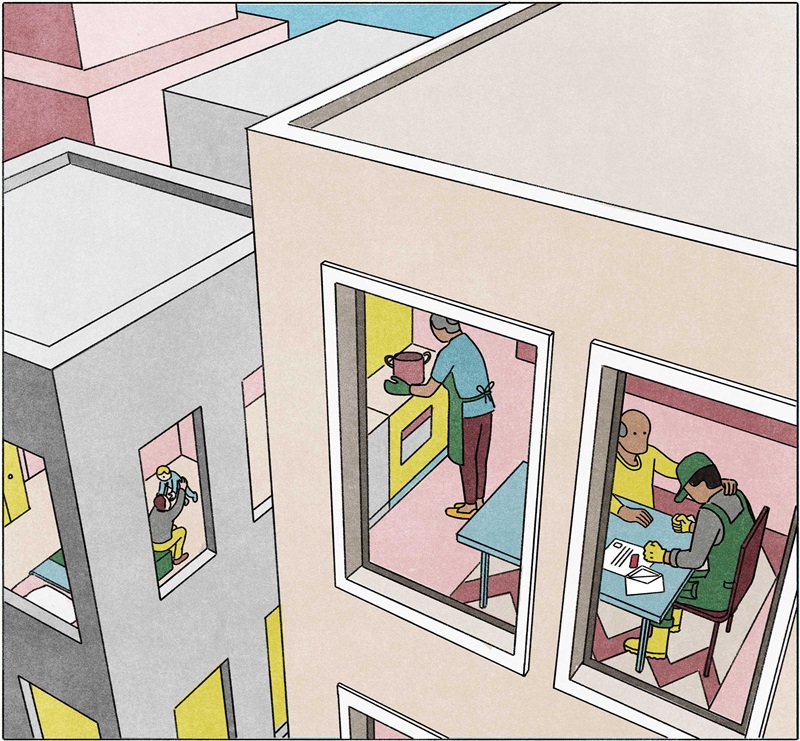

But does job loss affect all people in the same way? People born into families at the bottom of the income distribution face many more obstacles on the road to success than those born at the top. Obtaining a stable job is one way these individuals achieve upward mobility as adults. Do these workers experience the upheaval of a job loss in the same way as their colleagues who grew up in wealthier families?

New research by Institute visiting scholar Emily Nix and coauthors Martti Kaila and Krista Riukula shows that the path back to economic stability is much more difficult for workers from lower-income backgrounds. By linking adults in Finland to their parents’ earnings, the economists track employment and earnings around large layoff events for workers who appear similar but grew up in households with different income levels. Th e striking differences in the post-layoff experience of these groups shed new light on why job loss is so harmful and why economic status is so stubbornly persistent across generations. The coattails of one’s parents’ socioeconomic status are long.

Frictions and scars

Some amount of job loss is an inherent part of modern economies. The traditional view among economists holds that unproductive firms should fail. These models of the economy often imply that new jobs will be immediately available at the prevailing wage: no waiting, no wage cut, no matter who.

That approach is useful for analyzing long-run economic outcomes, but as unemployed workers know, in the short run, new jobs are not usually immediately available in the real world. Frictions in the labor market, like the time and effort it takes to get a new offer or the costs of moving to a city with more openings, mean that finding a new job is anything but immediate. It’s well-known in economics that people who lose their jobs usually remain unemployed for a spell while they search for new employment and that they earn less even after they get a new job, a phenomenon known as “scarring.” And while some workers bounce back quickly, others face consequences that are much worse than the average. But who are the worst-off workers?

Kaila, Nix, and Riukula tackle this question using a large and unique dataset of Finnish workers linked to their parents’ earnings. They look at workers who were laid off from their jobs due to firm downsizing and closures—in other words, people who lost their jobs through no fault of their own. They then measure how the earnings and employment of those displaced workers changed relative to the earnings and employment of similar workers who were not laid off.

The researchers make these comparisons separately for workers whose parents were in the top 20 percent and bottom 20 percent of the Finnish earnings distribution—the first time economists have studied how job scarring varies with parental income. This makes it possible to ask whether the scarring effects of job loss are related to parental economic status.

The answer is a clear yes. Two years after the layoff , the earnings of workers with lower-earning parents had fallen 18 percent compared to their previous earnings, whereas workers with higher- earning parents had lost about 9 percent. And despite similar earnings before the layoff, the earnings of those with less well-off parents remain markedly below that of their peers with wealthier parents for at least six years, as shown in the accompanying figure.

A key reason this happens is that workers with lower-income parents are only half as likely to hold a new job as workers with higher-income parents. This not only leaves them with fewer hours in which to earn, but previous research shows that unstable employment means displaced workers spend more time in lower-wage, entry-level jobs rather than reaping the benefits of experience at a new firm. “Even after entering the labor force, adult children of low-income parents have a more precarious perch on the job ladder compared with children of high-income parents,” the economists write.

Why parental income matters

The striking differences between workers whose parents earn different amounts raises a range of new questions about how labor markets work. “What exactly is it that those from poor families do not have (and those from rich families have) that affects their post-displacement outcomes?” asked Pawel Krolikowski, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland who has studied how displaced workers reenter employment and what factors facilitate their return. Does the advantage occur in childhood, adulthood, or both?

One potential explanation is that compared to lower-income parents, higher-income parents are able to better equip their children to withstand labor market shocks through more education. Higher-educated workers have smaller earnings losses than lower-educated workers, and the children of higher-earning parents tend to get more education. The economists show that differences in education—a “baked-in advantage”— can account for about half of the difference in post-layoff earnings losses.

But parental income matters outside of education, too. The authors find that workers with higher-income parents are not more likely to be hired into the same firm or industry as their fathers, but other forms of assistance are possible: cash gifts or loans, for instance, or leveraging professional networks.

The importance of parental income in determining the cost of job loss fits with other research showing a key role for families in shaping workers’ responses to tough economic times. Krolikowski’s research (with Patrick Coate and Mike Zabek) shows that living near one’s parents greatly mitigates the harms of job loss, and University of Chicago economist and Institute advisor Greg Kaplan documents how parents help their unemployed children by letting them move back home.

The notion that families matter for how workers respond to job loss has the potential to shift both policy and economic thinking on this issue. Retraining, job search, and income-support policies could be targeted to workers with lower- earning parents who are hurt the most by mass layoffs. Moreover, economic theories about how workers navigate labor markets after a mass layoff need to explain what parental income does and why it plays a role.

Kaila, Nix, and Riukula’s findings go beyond the economics of job loss, though. They also open the black box of one of the hottest topics in economics today: intergenerational economic mobility.

Inheriting resilience

Many countries view themselves as lands of opportunity—places where people who work hard can climb the ladder, no matter the rung they started on. However, extensive and compelling evidence suggests that boosting intergenerational mobility is much harder than we’d like to believe.

Kaila, Nix, and Riukula’s findings show that the disparate impact of job loss is an important factor undermining economic mobility across generations. After all, the groups they study were all doing well prior to losing their jobs when their firms laid off workers: The vast majority of those with parents in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution had moved into the top 60 percent—a way of saying that this group had achieved economic mobility.

But after a layoff, the economic status of workers with higher- versus lower-earning parents drifts further apart. One way economists measure intergenerational mobility is to look at how closely correlated a parent’s and child’s places in the income distribution are: When the children of rich parents become rich as adults and the children of poorer parents remain poor as adults, intergenerational mobility is lower. The economists find that that this correlation increases about 4 percent because of the disparate impact of job loss. This is true both because workers with lower-earning parents are more likely to be laid off than workers with higher-earning parents and because they work and earn less for years after a layoff. Both factors contribute to widening inequality.

Job loss in the age of COVID

Compared to the United States, Finland has more generous social benefits and higher levels of intergenerational mobility. There is reason then to suspect that the connection between parental income and the pain of job loss would be even stronger in the United States.

That impact is likely to reverberate even more during the age of COVID, when workers at low-wage jobs were far more likely to lose their jobs than workers earning higher wages. If people whose parents earn low wages face larger earnings losses for years to come, then the impact of the COVID recession on economic mobility and inequality could be substantial.

And job loss is just one feature of a labor market that workers experience, as Nix points out. Parental income might impact other features as well, such as the effect of entering the job market in a recession, the time it takes to find a job, or the impact of job loss on health. Studying these impacts will provide a more complete picture of just how long the coattails of parental socioeconomic status are.

This article is featured in the Spring 2022 issue of For All, the magazine of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute

Lisa Camner McKay is a senior writer with the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute at the Minneapolis Fed. In this role, she creates content for diverse audiences in support of the Institute’s policy and research work.