When the chief executives of Fairview Health Services and Sanford Health testified before Minnesota lawmakers in January, one lawmaker asked the Fairview leader if he had considered merging with another Minnesota hospital chain.

Fairview’s choice of a South Dakota merger partner had proven controversial, given the very different health care policies of the two states.

James Hereford, Fairview’s president and CEO, answered: “Frankly, no.” Hospital mergers in Minnesota have left many chains with overlapping markets, and mergers involving competitors will invite additional scrutiny from antitrust enforcers, he said.

Sanford’s hospitals are close enough to complement Fairview’s but not too close, he said. “What makes this so compelling is the contiguous nature, but nonoverlapping nature, of Sanford and Fairview Health Services.”

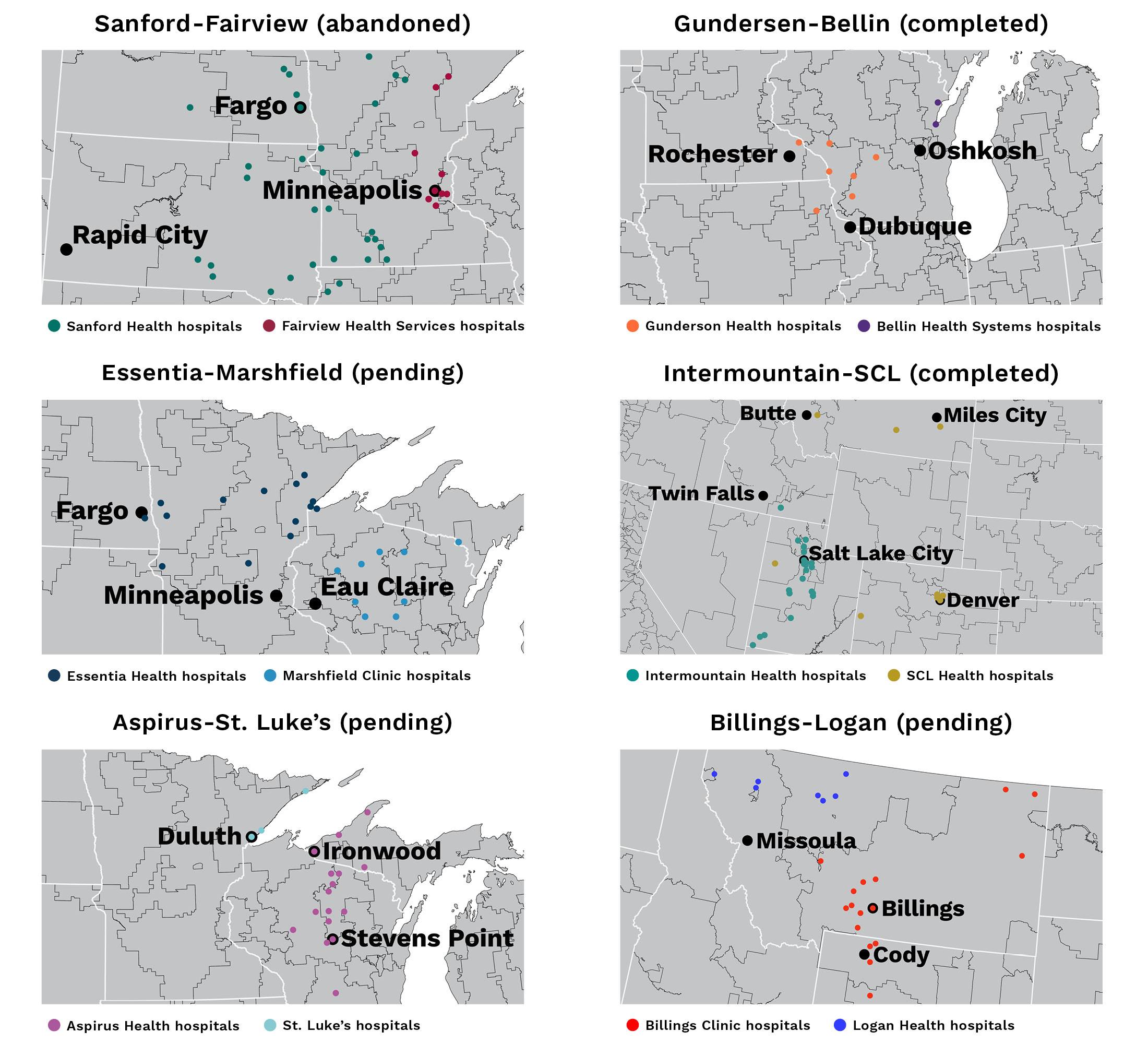

The proposed merger is what economists call a “cross-market merger,” and it has become one of the most common forms of hospital consolidation in recent years. Though Sanford gave up on its plans for Fairview under political pressure in July, many other hospital chains are exploring their own cross-market mergers, including three more pairs in the Ninth District.

A big reason for this is the logic articulated by Hereford. Another is that cross-market mergers, despite the appearance of not involving competing hospitals, may somehow affect competition. When cross-market mergers occur, economists have found, they often result in price increases.

“We don’t really know why,” said Christopher Garmon, an economist at the University of Missouri–Kansas City and a former Federal Trade Commission (FTC) official. For this reason, the FTC and Department of Justice have not challenged these kinds of mergers, he said. “That’s an area where we really need to better understand how hospital competition works.”

Market trends

Cross-market mergers involve chains that don’t compete head-to-head for patients.

To determine if hospitals are competitors, economists use regional hospital markets defined by the Dartmouth Atlas, metropolitan areas, or commuting zones. The Dartmouth method used in this article is based on where Medicare patients in each ZIP code tend to travel for certain advanced medical services.

In just the last couple of years, two cross-market mergers involving Ninth District hospitals were completed, three more are still in progress, and at least one has been abandoned (Figure).

These covered as much territory as the 2022 merger of Colorado-based SCL Health with Utah-based Intermountain Health—which involved eight markets stretching from eastern Montana to southwestern Utah—to as little territory as the 2022 merger of Gundersen Health System with Bellin Health Systems, both based in Wisconsin, which involved four markets from southeastern Minnesota to northeastern Wisconsin.

Minneapolis-based Fairview had hospitals in the Minneapolis and St. Paul markets, while Sioux Falls–based Sanford had hospitals in six markets from Great Falls, Montana, to Minneapolis. While they do have the Minneapolis market in common, the closest their hospitals get in this market is about 180 miles.

The two chains called off their merger in July citing opposition by “certain Minnesota stakeholders.” The merger was opposed by many state lawmakers and inspired a law that makes mergers tougher to pull off.

Cross-market mergers now make up a significant share of all mergers. Recent research has found that more than half of mergers in the past two decades involved hospitals or chains that don’t share the same metropolitan area or commuting zone.

Between 2016 and 2021, a Minneapolis Fed analysis found that more than half of the 179 hospital chains that gained new hospitals nationwide, whether through mergers and acquisitions or through new management relationships, also expanded into a new regional market. Among chains with a Ninth District presence, 24 gained new hospitals and nearly half of these also gained a new market. This analysis includes only general hospitals, not specialized hospitals.

Many of these cross-market activities around the nation involved modest-sized chains. The median number of hospitals that chains end up with after cross-market consolidation was six. The larger the number of new markets a chain expands into, the larger the number of hospitals. For chains gaining more than two markets, the median number of hospitals was 23.

Cross-market activities in the Ninth District tend to involve much larger chains than is common nationwide. Chains gaining at least one market end up with a median of 16 hospitals.

A Sanford-Fairview merger, based on the hospitals they controlled in 2021, would have created a 51-hospital chain. Even a more modest merger, such as Gundersen and Bellin, created a 10-hospital chain.

Bigger is better?

In explaining the benefits of their merger to the public, Essentia Health, based in Duluth, Minnesota, and Marshfield (Wisconsin) Clinic made arguments that many merging hospitals offer: It will allow them to do more for patients.

When they announced in October their proposed merger into a chain with hospitals from North Dakota to southeastern Wisconsin, they argued this “will lead to more opportunities to expand needed services and provide high-quality care at an affordable cost with an excellent patient experience.”

The way a merger would achieve this, many hospital executives say, is through “economies of scale” and access to greater resources.

Larger hospital chains tend to receive better credit ratings, in part because of their greater financial resources, which reduces their borrowing costs. This allows them to invest more in their facilities and their employees, which helps them compete for patients and gain market share.

Larger chains are also large purchasers of goods and services, giving them more leverage when negotiating with vendors for lower per unit costs. In some cases, chains benefit from fixed costs, such as the very expensive information technologies used to coordinate care. The cost of this technology does not scale with patient numbers, so large and small chains pay about the same. But large chains can spread those costs across more patients.

Hospital chains need not engage in cross-market mergers to enjoy these benefits. In fact, experts say economies of scale tend to be stronger when hospitals are closer together. Supply chains are more efficient when hospitals share one warehouse. Medical services can be consolidated in fewer hospitals if they’re within easy driving distance of patients.

But, because regulators frown on mergers involving hospitals that are too close, chains like Sanford and Fairview look for merger partners just outside of their markets.

A different type of market

Aside from less antitrust scrutiny, cross-market mergers do offer certain benefits over in-market mergers.

Expanding into new regions allows chains to access more profitable markets, such as those with higher-income households or with growing populations, and to diversify their markets to reduce financial risks.

But the consumer market is not necessarily the only or even the most important market for hospitals. Economists who study cross-market mergers note that insurers have a lot of control over markets because they’re the ones paying for medical services. An advantage of having hospitals in multiple markets is the leverage it offers chains when negotiating with insurers.

“If you’re United Health Care [a Twin Cities–based insurer], you’re trying to develop a provider network that’s attractive to Wal-Mart, to the Home Depots, and FedExes of the world that have employees across all these markets,” University of California Berkley economist Brent Fulton said recently on A Health Podyssey podcast. “When hospital systems merge and grow larger and larger, there’s fewer alternatives.”

The most important customers for major insurers are major firms with employees in multiple states. Those firms prefer to offer the same health insurance plan to all employees, which means insurers would want to offer access to multiple hospitals in most markets. Hospital chains that have a significant though not necessarily dominant position in many markets can undermine this goal by choosing to not participate in an insurance plan.

Economists have found that increased bargaining power allowed chains to increase prices by 7 to 17 percent after cross-market mergers. Some found even higher price increases when mergers involve contiguous markets.

But the insurance industry is consolidated too, and hospitals say they need to consolidate to maintain leverage. According to a 2022 American Medical Association report, 75 percent of metropolitan regions in the U.S. had highly concentrated insurance markets. In the Ninth District, that figure was 60 percent.

Cautious regulators

Given the link between cross-market mergers and higher prices, some economists have urged the FTC and other antitrust enforcers to challenge such mergers more aggressively. To date, only one has been challenged.

According to Mark Seidman, an assistant FTC director, regulators are paying attention, but decades of experience has taught them that to convince judges that a hospital consolidation harms consumers, they must be able to explain how.

“You can identify the outcome, but if we’re going to go into court and stop a merger, we need to be able to explain to the court the mechanism,” he said at a University of Pennsylvania seminar earlier this year.

Currently, hospital competition is mainly viewed through the lens of consumer markets, not insurance markets.

Garmon, the former FTC economist, said regulators lost many hospital merger cases in the 1990s because they lacked the tools, including the right definition of market, to explain the effect on competition. “At one point, the FTC and [Department of Justice] lost like eight straight mergers. So, by 2000, effectively there was no hospital antitrust enforcement. I mean it was done.”

They only succeeded after a lot of research, including new ways to measure the loss of competition, he said, citing work he and his FTC colleagues were involved in. “That led to the FTC starting to challenge hospital mergers again and being more successful at it.”

Tu-Uyen Tran is the senior writer in the Minneapolis Fed’s Public Affairs department. He specializes in deeply reported, data-driven articles. Before joining the Bank in 2018, Tu-Uyen was an editor and reporter in Fargo, Grand Forks, and Seattle.