There are a little over 330 million Americans. Around 221 million of us live in a house, condo, apartment, or mobile home that we own. Another 103 million rent, 2.7 million live in dorms, 2.2 million live in jails and prisons, 1.3 million live in nursing homes, and 360,000 live in military accommodations.

At least 600,000 of us, however, live nowhere.

Of course, nobody lives nowhere. Homeless people live in the woods, on commuter trains, in alleys, doorways, parks, encampments, or cars. Some crash with friends or relatives. Others get vouchers to spend a few nights in a motel. Many live in shelters.

What do 600,000 homeless people mean for America? Labor markets, housing markets, and a suite of public policies aimed at low-income and homeless people put a roof over most of our heads, but they do not eliminate what is one of the hardest facets of American life. Many people do end up on the street. Many more fear that they will.

“Homelessness captures the well-being of some of the most vulnerable in the country,” said Krista Ruffini, assistant professor at Georgetown University and co-author of a recent summary article on homelessness interventions. “It is illustrative of what’s going on at the very bottom of the income distribution and so it warrants a policy response.”

But what might a solution to homelessness look like? Increasingly, economic research considers not only outreach teams serving people on the street, service organizations expanding shelter space, or counselors addressing addiction but also broad changes to markets and safety nets that involve—and affect—all of us.

People

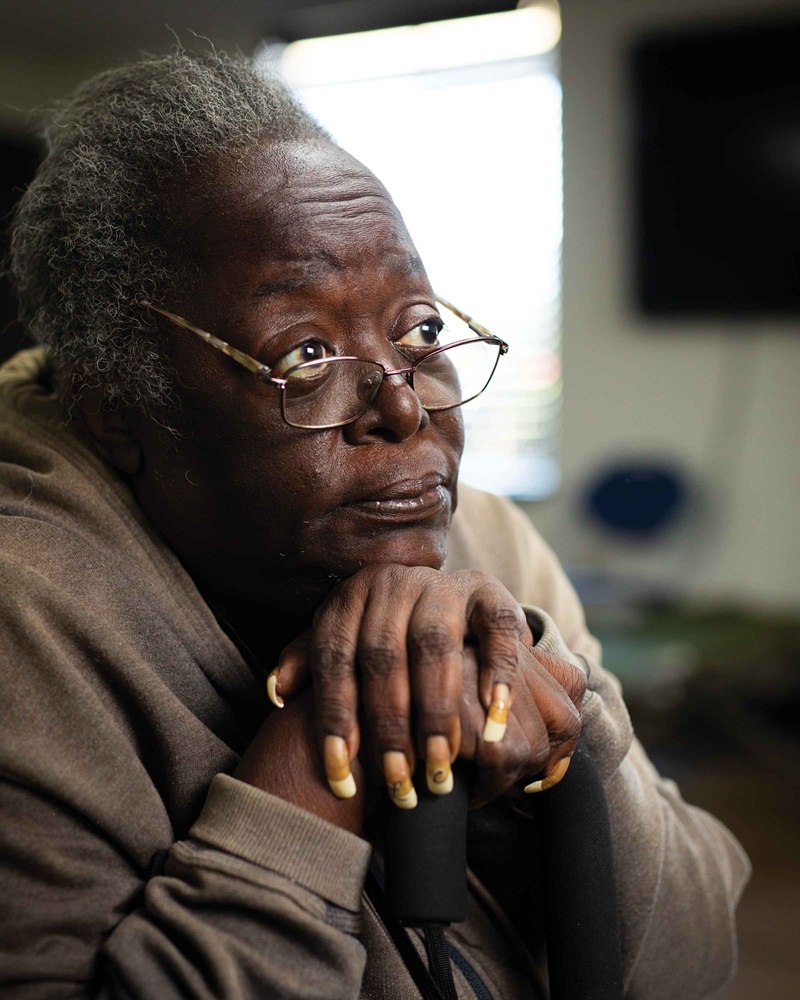

When I sat down in a St. Paul, Minnesota, men’s warming shelter one night in January 2023, I met a stream of men with nowhere else to go. I had signed up to help the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) count America’s homeless population. Many men arrived on foot and waited in the cold until doors opened. Some showed up after their work shifts ended. A shuttle driver stopped every so often to drop off more men who would not have been safe on a night with temperatures in the teens.

“I think of homelessness as a late 20th century, early 21st century phenomenon,” said Brendan O’Flaherty, a Columbia University economist who has been studying homelessness longer than almost anyone. In his 1996 book, O’Flaherty recounts how in New York City, social scientists uncovered so few people sleeping on the street in 1964 that they stopped counting. Researchers in Chicago and Newark found a similar situation. But by the 1980s a homelessness problem was obvious. One HUD report concluded that there were between 250,000 and 350,000 homeless people in 1984. In the first attempt at a nationwide homeless count, the Census Bureau found 228,000 homeless people in March 1990. Its methodology, however, may have missed half of the unsheltered population. By 2007, HUD mandated that local areas conduct the modern Point-in-Time counts.

It was not hard to count the 30 or so men in the warming shelter that night in January, but counting all the people experiencing homelessness in the Twin Cities—or the country—is much easier said than done. Even defining homelessness presents a major challenge. In the U.S., if you sleep outside in shelter not designed for habitation (like a bus station), in an emergency shelter (including domestic violence shelters), or in a longer-term homeless shelter, you are homeless. You are not homeless if you are an adult staying with friends or family, but if you are a student doing so, you are homeless. You are not homeless if you sleep in a hotel that you pay for with your own money, but you are homeless if you pay with a public voucher. You might not be homeless if you live in an RV, but you are homeless if you live in a car.

The second difficulty comes in applying this definition. Many unsheltered homeless people cannot be found. Others, like two men I spoke to, refuse to be counted. And because HUD counts people who are homeless on one night, they miss the majority of people who are homeless for brief periods during a year. A 2018 study suggested that the number of people across the state of Minnesota who experienced any period of homelessness in a year was about 2.5 times as many as were homeless on a given night.

Despite the conceptual and practical hurdles, shelter workers, public employees, and volunteers counted about 5,000 homeless people in the counties containing Minneapolis and St. Paul in January 2023, a number mostly unchanged since 2007. That number is 2 percent of people in poverty and about 0.3 percent of Twin Cities residents, which is about two-thirds higher than the national rate.

Whether this is a small or large number depends on your frame of reference. But the deep costs of homelessness for the people who experience it and the way this population affects other people and public systems add up to a substantial problem.

need

Homelessness imposes costs on all of us.

For most, these costs are indirect. Seeing people openly use drugs or in mental distress can be scary or dangerous. That fear has implications for many public services. For example, a few hundred homeless people ride the Twin Cities light rail, which is legal, warm, and open almost all night. Their presence, however, puts off riders and requires so much attention from transit workers that the state is considering boosting security to “reset” the culture and perception of the system.

Other costs relate to space. Unsheltered homeless people live in public places by definition, but parks and sidewalks full of tents are no longer really parks and sidewalks. From January 2022 to March 2023, Minneapolitans made more than 1,700 calls to 311 to register complaints about homeless encampments. One such call, detailed in a City of Minneapolis report on homeless encampments, stated “the children in the school have not been able to play at the playground due to the presence of these individuals, their drug paraphernalia, and human feces.”

Polling suggests that the burden of homelessness is widely felt. The overwhelming majority of respondents to recent polls—typically more than 80 percent—agree that homelessness is a major issue, and in areas with large homeless populations, like California and Oregon, a plurality of respondents think it is the most important issue.

Ultimately, though, the Americans who are homeless suffer the most. In 2018, half of homeless people in the Twin Cities earned less than $600 per month, putting them in the poorest 5 percent of the population. One-quarter of homeless adults in Minnesota were physically or sexually attacked while homeless. Between 2017 and 2021, people who used homeless services in Minneapolis died at three times the rate of similarly aged Minnesotans.

Because we all experience these costs, albeit to wildly differing degrees, we share a need for solutions. The United States Interagency Council on Homelessness provides one vision in its 2018 Federal Strategic Plan: Make homelessness “rare, brief, and one-time.” This would shrink homelessness counts, protect vulnerable people from becoming homeless, and alleviate burdens on public budgets and spaces. But devising such policies, especially given the diversity of the homeless population (described in “Taking stock of homelessness in the United States”), is daunting. Increasingly, researchers are taking on that task.

a place

For the chronically homeless, including people whose substance use or mental illness creates the largest costs to their communities, research tells us what to do: Give them housing. Instead of offering temporary housing and mandatory treatment, the predominant approach in the 1980s, the approach called Housing First immediately gives people a stable place to live. Specific rehabilitation services are offered but, crucially, not required.

Randomized trials repeatedly show that Housing First keeps people housed. One study took a group of families staying in homeless shelters and offered some a permanent housing voucher, while others received the shelter’s normal services. After three years, 16 percent of the permanent housing voucher group had been homeless or doubled up with friends and relatives in the previous six months, compared with 34 percent of the families receiving the usual care.

Another study of homeless veterans with psychiatric or substance use disorders came to similar conclusions. And Elior Cohen, an economist at the Kansas City Fed, conducted a large-scale study of applicants for homelessness assistance in Los Angeles County and found that housing reduced the probability of homelessness by two-thirds after 2.5 years.

Perhaps the most striking feature of Housing First, though, is that in some cases it does more than just house people who are homeless. Mothers offered permanent housing reported lower rates of intimate partner violence (a major finding given that one-third of homeless women are fleeing domestic abuse), less psychological distress, better food security, and fewer behavioral problems with their children. Cohen found that in Los Angeles, providing housing reduced criminal activity and increased employment. What’s more, these positive impacts do not appear to involve a trade-off for Housing First clients: People given housing and voluntary treatment services do not report higher rates of drug or alcohol use than people made to complete treatment programs first.

On the strength of this evidence, Housing First programs are the main way that local providers treat homelessness today—a big shift from 40 years ago. True, permanent housing costs more than the usual care offered by shelter services, because agencies must pay landlords for as long as recipients remain eligible. But to the extent that secure housing stabilizes clients’ lives, it sometimes lowers public spending in other domains.

Housing First, however, cannot realistically eliminate homelessness in the U.S. Too many people live on the precipice of losing their housing. HUD found that in 2019, 44 percent of low-income people spent over half their income on rent. They are housed, but unstably—an unexpected medical expense or a job loss could push them into homelessness. So even if policymakers want to or could house every person who is homeless today, what would happen tomorrow?

to live securely

“I used to think, like many other people, that homelessness was a mental health problem,” said Ayse Imrohoroglu, economics professor at the University of Southern California Marshall School of Business. “But then I realized that a very large fraction of the homeless are homeless due to shocks, and economists know how to deal with shocks.” Inspired by the soaring homelessness around her in LA, Imrohoroglu decided to study homelessness not with randomized evaluations but with economic theory.

With co-author Kai Zhao, Imrohoroglu constructed an economic model of people who not only purchase homes, rent apartments, consume, save, and work but also lose jobs, get sick, and sometimes become homeless. By building in interactions with policy and housing markets, the model shows that preventing homelessness is key, and the reasons why people become homeless shape which policies keep them housed. Rent subsidies for the cheapest units or expanded housing voucher availability, for example, ensure affordable options for people who might otherwise have been homeless for a short time. However, these programs do little for people unable to work for long periods. Income support, especially for those with health problems, can protect this group from chronic homelessness, but to do so on a large scale, this protection needs to be both generous and well targeted to poor people.

Data also support the importance of preventing rather than just curing homelessness. For example, every year 75,000 people call a Chicago hotline that provides a few hundred dollars to people facing eviction, but because funds are limited, only a fraction of them get help. About 3 percent of the callers whose requests get no money because they happen to call when funds are already exhausted use homeless services in the following six months. The share is less than 1 percent for callers who do get financial help.

Because homelessness is so hard to predict—even among those who call prevention hotlines—help has to be broadly available to reach the people who might actually become homeless. It also has to help people afford the housing that is available at prevailing prices. Another line of thinking, however, focuses on the price side of the equation, widening the scope of homelessness discussions to include housing markets themselves.

and affordably

A collection of suggestive evidence supports the idea that housing markets are responsible for homelessness. For instance, city-level homelessness is more related to rents than it is to poverty, substance use, or mental illness. This is not to say that individual challenges don’t matter—they do—but the housing view emphasizes that when rents are high, even small disruptions can make people homeless. Turning a story about housing markets into effective homelessness policy is difficult, however. “The best policy is probably to reduce housing prices,” O’Flaherty said, “but we don’t know how to reduce housing prices.”

One common housing market reform to lower prices involves making it easier to build by removing regulations. Housing economists suggest two ways that new market-rate construction, which many zoning reforms seek to encourage, might ultimately lower the prices faced by people at risk of homelessness. First, through the movement of tenants: New units attract residents who vacate other units, creating more vacancies that must be filled, and so on. Upjohn Institute economist Evan Mast, in research presented at a Minneapolis Fed 2019 Institute conference, traces those moves and shows that higher-rent construction creates substantial vacancies for people in the middle of the income distribution.

Second, through housing deterioration: Studies show that as a property ages, its price falls and it tends to pass to poorer people. This “filtering” of housing down the income distribution is another link between construction now and housing supply for lower-income people later.

Both stories capture some truth, but a direct connection with homelessness is hard to establish. Mast found that up to 15 percent of moves created by new market-rate construction were made by people living in the poorest 20 percent of neighborhoods, but it was impossible to learn if any of them would have been homeless had they not moved. Nationally, one 2007 study found positive correlations between the stringency of a state’s housing regulations, housing cost burdens, and homelessness. But this is at best a long-run relationship, because building takes time and filtering takes even more time.

A fundamental factor that keeps deregulation from being a quick and effective homelessness policy is that building is very expensive. The average new home in 2022 cost $168 per square foot to build, putting the cost of a 1,600-foot house (close to the 25th percentile size in 2022) at $268,800, well out of reach of lower-income Americans.

As a result of high costs, most new affordable housing gets built because of subsidies. Consider the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority’s current plan to build 84 new units. Officials estimate a total cost of $34 million dollars, or over $400,000 per unit. To fund it they tapped pandemic relief funds from the City of Minneapolis, economic development grants from the City and the Metropolitan Council, federal loans earmarked for affordable housing, Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC), and traditional mortgage financing.

The housing built with these subsidies does reduce homelessness, to an extent. Research by Boston Fed economist Osborne Jackson and University of Michigan economist Laura Kawano shows that LIHTC-funded developments increase the supply of affordable housing in a neighborhood and reduce county-level homelessness rates. Kevin Corinth, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute, found that 100 new beds in permanent supportive housing units, which incorporate rehabilitation services on-site, reduced aggregate homeless counts by about 10 people.

But these reductions in homelessness are not very large and come at a high cost, which limits what subsidy dollars can do. Reducing those costs is therefore key to getting housing markets to serve low-income people more effectively. Localities could start allowing single-room occupancy buildings, Corinth points out, lowering per-unit costs by making the units smaller. In Minneapolis, a new transitional housing space, Avivo Village, does just that by providing 100 indoor tiny homes, which cost just $22,000 per unit to build.

Minneapolis Fed economist James Schmitz has another idea: Let factory housing in. Manufactured housing, in which entire structures are produced efficiently en masse and delivered to a site, cost just $88 per square foot in 2022—half the cost of site-built housing. Today just 9 percent of new housing in the U.S. is manufactured housing, but places where it is most common, like Mississippi, have some of the lowest homelessness rates in the country, according to data Schmitz gathered from the Manufactured Housing Institute.

Manufactured housing faces many barriers, however, said Libby Starling, senior community development advisor at the Minneapolis Fed. Legal restrictions limit where such homes can go. It’s difficult to tailor mass production to hundreds of local building codes. But breaking through these barriers may not only reduce homelessness, said Schmitz, it could have implications for the location, size, and cost of housing for many of us.

Policymakers across the world struggle with issues of housing affordability and homelessness, albeit very differently. Two-thirds of Viennese renters live in public housing, much of it gorgeous. Turkey technically has only a small homelessness problem, Imrohoroglu told me, because very poor people build shacks and consider themselves housed. In the U.S., people are homeless when poverty and instability collide with expensive housing. But whether it is best to take on poverty or housing remains an open and vital question.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in the midst of the homelessness crisis created by the Great Depression, proposed a second Bill of Rights which included the right of every family to a decent home. “We cannot be content,” he argued, “no matter how high that general standard of living may be, if some fraction of our people—whether it be one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth—is ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and insecure.” Today homelessness is an acute disaster for some and a nuisance for others. The conditions that create it, however, matter deeply for all 330 million Americans who share a simple reality: People need a place to live.