A national government with significant debt and tenuous finances can expect skepticism from global creditors when it comes time to refinance (or “roll over”) that debt as it comes due. If lenders expect the debtor country might default in the future, they could balk at purchasing new bonds at any interest rate the country could afford to pay. In such a “rollover crisis,” these fears can ironically push the debtor into default today, leaving current creditors in the lurch.

The better we understand the dynamics of such self-fulfilling crises, the more likely we can avoid them for the global good. In a new Minneapolis Fed working paper, Monetary Advisor Javier Bianchi tackles a common dilemma faced by debtor governments: When a government anticipates challenges rolling over its sovereign debt, should it reduce its debt or should it acquire more assets in the form of international reserves? (See Working Paper 805, “International Reserve Management under Rollover Crises,” with Mauricio Barbosa-Alves and César Sosa-Padilla.)

The motivation to acquire assets is understandable. Building up such international financial reserves would provide valuable resources and liquidity in the event that a default leaves the country cut off from additional borrowing. It is among the actions sometimes advised for indebted developing countries by the International Monetary Fund.

Although acquiring reserves might bring some semblance of stability at a precarious moment, Bianchi and his co-authors demonstrate that for a government moderately or highly indebted, building up reserves is likely not the right prescription. There is an inflection point, however—once a country has cut its debt sufficiently—when acquiring reserves becomes optimal.

In a simple scenario where all debt comes due and gets rolled over at once, Bianchi and his co-authors say the case against adding reserves amid a crisis appears open-and-shut. Reserves will typically earn a lower interest rate than the government pays on its debt, deepening the immediate financial imbalance. Higher reserves also make a hypothetical default less painful for the debtor. In the calculations of potential lenders, this makes a future default more likely. These lenders might therefore demand higher rates to roll over the debt of a government seen adding to its reserves, precipitating a near-term default. Rather than shore up reserves, the debtor government should focus exclusively on trimming its spending and paying down its debt.

However, actual sovereign debt has various maturities, which come due only a fraction at a time. In this setting, the economists find it can be optimal for a country facing rollover risk to add to its reserves, taking on additional debt to do so—but only late in the game, when this constitutes the last step to emerge from the crisis. When this finish line is attainable, the usual logic on reserves is reversed. Using debt to acquire reserves relaxes the government budget constraint if investors suddenly become unwilling to roll over the debt, raising the value of repayment versus default. This actually lowers the sovereign spread (the interest rate premium demanded by creditors) as these creditors perceive the receding risk of default.

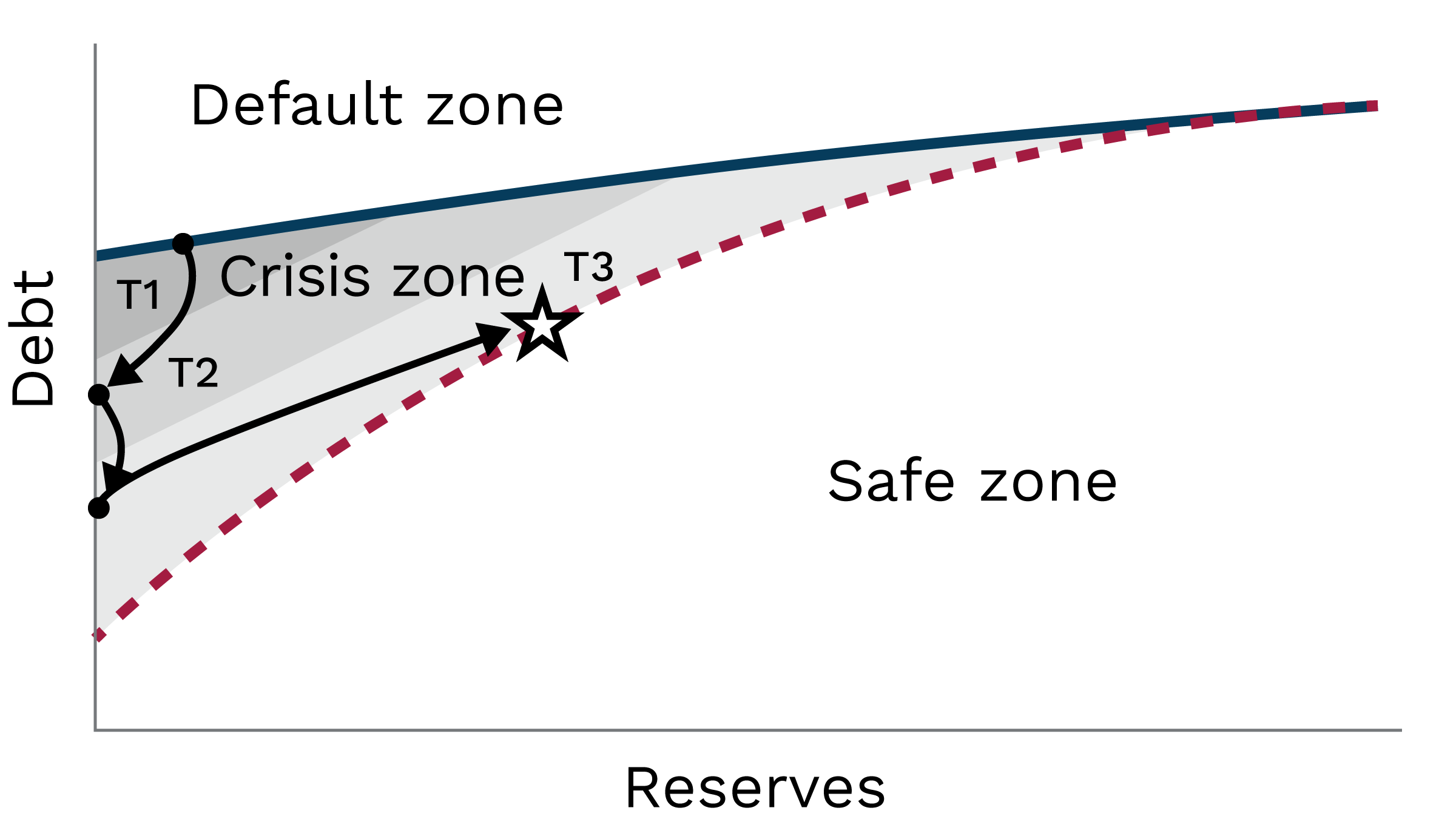

In the model developed by the economists, the government can inhabit one of three zones: a “default zone” where default is rational, a “safe zone” where there is no risk of default, and a “crisis zone” where government repays if creditors are optimistic or it defaults if creditors turn pessimistic. The question tackled by the authors is whether reserves can help a government escape the crisis zone.

Source: “International Reserve Management under Rollover Crises” by Barbosa-Alves, Bianchi, and Sosa-Padilla.

In graphical form, the debtor government’s value functions define the boundaries of the three zones (see figure). The economists’ mathematical model reveals how a government in the crisis zone—given any initial position of net foreign assets (debt and reserves)—should optimally choose debt and reserves across a series of moves to exit to the safe zone and minimize the risk of a self-fulfilling, rollover default.

In the three-period example shown here, a government begins deep in the crisis zone. Exiting in one or two periods would require severe austerity. Its optimal path is therefore only to decrease debt in the first two periods, expending any existing reserves to do so.

Holding or acquiring reserves during these initial periods would make the ultimate deleveraging more painful by forcing the government to reduce even more consumption as it attempts to exit the crisis zone. As repayment becomes more onerous, investors perceive higher odds of default and become more reluctant to roll over the debt. The rollover crisis tilts into a self-fulfilling default.

In the final period, however, reserves switch from a negative to a positive factor. The government’s optimal action in this case is to take on substantial reserves, facilitating its final push to reach the safe zone and put the rollover crisis behind it.

The economists calibrate their model using parameters from the Italian debt crisis of 2012. Once the model is calibrated, they determine that the optimal quantity of final-period reserves depends crucially on the maturity of the debt. When a larger fraction of debt is coming due each period, the final move will entail a larger purchase of reserves to reach safety.

Reserves appear to be a valuable part of the formula for a country seeking to emerge from under the cloud of a rollover crisis. When the economists remove from the model any option for the government to build reserves, they find that a government takes longer and must cut consumption more deeply to reach the safe zone.

Read the Minneapolis Fed working paper: International Reserve Management under Rollover Crises

Jeff Horwich is the senior economics writer for the Minneapolis Fed. He has been an economic journalist with public radio, commissioned examiner for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and director of policy and communications for the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. He received his master’s degree in applied economics from the University of Minnesota.