Across states, most public education systems are organized in relative similarity. Nationwide, state-run university systems widely mirror each other—a land grant institution, which might or might not double as a major research university, complemented by a handful of state universities.

Compare that with the hodgepodge of community and technical college systems in district states. While there are obvious similarities—all district states have community or technical colleges or both—there are also a surprising number of differences in structure and governance (see sidebar) as well as in the breadth and depth of two-year education systems in the district.

In the end, much of the difference among district states can be traced to the degree to which individual two-year systems serve the changing demands of students and employers, and reflected in such things as the availability of shorter-term programs and the maturity of customized training programs that directly target employers.

Does size matter?

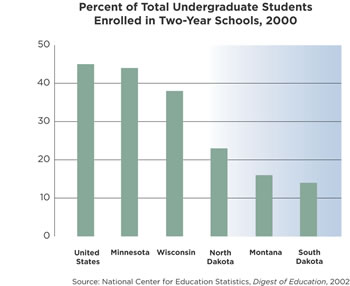

A quick glance at enrollment figures shows that Montana and the Dakotas have proportionally smaller two-year enrollments compared with Minnesota, Wisconsin and the nation, even after factoring for small state populations (see chart).

Montana has seen two-year enrollments grow 23 percent from 1997 to 2003, while four-year college enrollment rose barely 4 percent—a growth rate gap that is expected to widen considerably by 2007, according to system data. Despite that growth, it's expected that for every single two-year student in Montana in 2007, there will still be seven students attending a four-year state university.

In South Dakota, fewer than one in six undergraduate students are enrolled in a two-year program. Fewer than one in four undergraduate students in North Dakota are in two-year programs, compared to a national rate of almost 45 percent.

"North Dakota has an underdeveloped community college system," said Eddie Dunn, a vice chancellor with the North Dakota University System. "I think it's a carryover of an old philosophy" whereby the two-year schools were junior colleges whose sole purpose was to feed into four-year colleges, he said.

Much of the emphasis, or lack thereof, on two-year colleges "is a function of the higher education system in the state. In both the Dakotas they've been underdeveloped," in part because of a strong emphasis on four-year programs, according to Dennis Jones, president of the National Association for Higher Education Management Systems. "College means going away and going full time," both of which run counter to the typical experience at two-year colleges, where students are local and many go part time, he said.

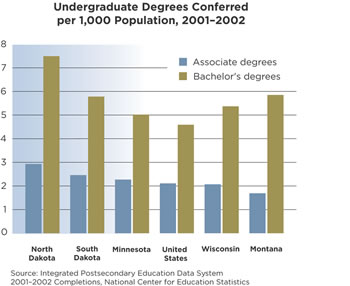

One might think this means that associate degrees are rare in Montana and the Dakotas. It's difficult to say exactly how many is too few, too many or just the right number of associate degrees for a state. But by most measures, Montana's two-year system lags both the nation and district in terms of students and associate degrees awarded, in some cases by a large margin.

That doesn't appear to be the case in the Dakotas. Despite comparatively low two-year enrollments, North and South Dakota both manage to crank out a high number of associate degrees on a per capita basis, and they also fare well in the proportion of associate to bachelor's degrees (see chart).

They manage to do so because of abnormally high numbers of full-time students. Nationwide, not quite two of five students at community and technical colleges attend full time, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics; in North Dakota, almost two-thirds of such students go full time; for its southern neighbor, better than three-fourths do so.

Short sorts

Much bigger differences in two-year systems can be seen in short-term programs below associate degree—in other words, programs that are less than two years in length that are often very occupation specific, like desktop and Web publishing, travel and real estate agent, dental assistant and myriad others.

In this area, Minnesota and Wisconsin have distinctly more mature technical and community college systems than the Dakotas and Montana (see chart for awards across all levels, by state). The number of short-term diplomas awarded by the Wisconsin Technical College System rose 68 percent from 1993 to 2002 and now make up 40 percent of all WTCS awards. The number of associate degrees and all other award or completion categories dropped over the same period for WTCS, with the exception of a minuscule increase in the number of college-parallel awards.

In something of a chicken-or-egg scenario, neither the Dakotas nor Montana offers many short-term programs. All three states also tend to rank low in terms of the number of working adults enrolled part-time as undergraduates—the majority of whom tend to populate two-year colleges because of both proximity and program flexibility. Nationwide, 6.2 percent of 25- to 44-year-olds were part-time students in 2000. Montana's rate is barely half that (3.3 percent), while North and South Dakota's rates were closer to 4 percent. Minnesota's rate was a shade under the national average, while Wisconsin matched it.

Arlene Parisot, a director with the Montana Office of the Commissioner of Higher Education, acknowledged the issue. "There aren't many [short-term programs] and probably need to be. That's a direction we need to go."

(A growing pool of private and nonprofit institutions and career colleges also offer everything from associate degrees to short-term occupational certifications. Combined they make up less than 13 percent of all enrollees in two-year programs in all district states, and less than 3 percent in the Dakotas and Wisconsin. Nationwide, they provide about 20 percent of all associate degrees, though their contributions in district states was unknown and likely much smaller. For awards requiring less than two years of schooling, nonprofit and private firms gave out 47 percent of all such awards nationwide in 2002, but their distribution in district states was also unknown.)

Customized training

A different but related area of growth for many two-year systems has been in customized training—short-term, nondegree programs that are specifically designed for industry and individual firms to upgrade employee skills.

Again, Minnesota and Wisconsin have by far the most sophisticated customized training programs, even for their proportional size. Wisconsin technical colleges completed some 5,600 contracts for training and technical assistance in 2002, involving 124,000 workers. MnSCU reported that some 6,000 companies and 140,000 employees received customized training services in 2002, the vast majority in two-year colleges. By contrast, customized training programs in the Dakotas and Montana typically cite about one-tenth those figures.

Many see customized training as an iceberg market—there's still a lot lying under the surface. "We believe the importance of customized training will grow as employers and employees see the need for acquiring new skills to keep up with the changing job market," said Linda Kohl, associate vice chancellor for public affairs for MnSCU.

North Dakota has made a considerable jump in a few short years. Customized training in North Dakota didn't really get started until 1999 when the state Legislature split the state into quadrants and assigned a two-year college to oversee the development of a workforce training program in each region. Since then it has managed significant growth.

But first rewind more than a decade, when there was growing demand from employers for workforce training, and a state higher education system that "was not able to meet that growing demand," according to an April 2004 report on the matter. In the first half of the 1990s, the state made several attempts to rectify the problem, but the system was still not up to snuff. A 1998 task force concluded "that North Dakota's workforce training system is fragmented, underdeveloped, duplicative and incapable of meeting the current and rapidly changing workforce needs of business in the state," and recommended that "major changes are urgently needed."

So after some due diligence regarding best practices in other states, it tried again. Using the widely heralded model of Kirkwood Community College in Iowa, two-year colleges in North Dakota were given primary responsibility over the state's training system. The new system focused first on creating a customized training core, giving birth to the quadrant approach. From 2000 to 2003, the number of businesses that received training services increased 188 percent to almost 1,500 businesses annually, involving almost 10,000 workers, according to a 2003 university system accountability report. Employers and employees alike have reported satisfaction rates with training received exceeding 95 percent.

Not recession-proof

The recession has been a pretty serious speed bump for many customized training programs, as discretionary dollars for training from both the government and private sector tend to dry up when budgets get tight or business is slow. In North Dakota, for example, the number of workers in customized training programs dropped between 2001 and 2003 (though some of this is attributed to program expansion into rural areas, which made training available to smaller businesses with fewer employees).

The four tech schools in South Dakota did customized training for about 9,100 workers in 690 different classes in 2002-03. "That was the lowest it's been in several years," according to Gary Williams, director of the Lake Area Technical Institute in Watertown. Four years earlier, the colleges trained more than 11,000 in 860 classes. "Pretty good for only having 750,000 people in our state."

Wisconsin peaked in 2000 in terms of contracts and students, though it has managed to continue increasing total revenue. Jeff Dodge, dean of continuing education for Wisconsin Indianhead Technical College in Shell Lake, said via e-mail, "Businesses have pulled back. We have lost industry in the area to overseas operations [and] these were good customers." But he also mentioned that grant funding for various government agencies has brought in a lot of business in the last two years. Dodge also expected business to pick up because of the rebounding economy, and because of possible state training initiatives to keep state manufacturing competitive.

As the saying goes, it was the same but different for Nicolet Area Technical College, in Rhinelander, Wis., which averages just over $250,000 in customized training revenue each year, according to Sandy Bishop, a training coordinator for the college. The program "initially experienced some hesitancy on the part of business and industry to commit to customized training contracts with the college, especially in the manufacturing sector," Bishop wrote via e-mail. But government training in areas like hazardous materials and emergency response training dipped as government funding got tighter, Bishop said.

Still, Bishop said, "our customized training business is currently as strong as ever." One of the reasons is a new strategy to identify groups of employers that share similar training needs. This allows the college to offer training to multiple employers at the same time, which lowers per-student instruction costs, and stretches training dollars further.

At a time when state appropriations to higher education have been stagnant or sagging, many see customized training as a niche that can not only help local employers and workers, but also help plug financial holes at colleges that many see as last in line when it comes to state appropriations.

Morrie Anderson, former MnSCU chancellor and currently a higher education consultant, called customized training "the leading edge" in aligning supply and demand for skill training. He added that such programs "are a cash cow for most campuses" because the revenue earned is discretionary and can be spent as the college sees fit, unlike with state appropriations.

And the revenue earned is hardly trivial. In 2001-02, Wisconsin technical colleges earned campuses a combined $24 million. In Minnesota, customized training revenues were as high as $19 million in 2001, though the recession pulled the figure below $17 million a year later. And recession aside, these revenues are likely to increase going forward as colleges and local employers see mutual benefit from customized training programs.

Despite customized training being a likely growth market for two-year colleges, there are still issues to be faced and improvements to be made in most states. Anderson, for example, noted "almost a hostile relationship" between customized training programs and traditional two-year programs in Minnesota. "Very little flows into a curriculum environment in most cases," Anderson said, adding that some customized training contracts offer the opportunity, for example, to create a curriculum template for a particular industry. This template could then be used in the classroom and proactively marketed to help other firms in the same industry.

At Western Wisconsin Technical College in La Crosse, manufacturing and government spending on training have both slowed, though contracts (averaging about 200) and revenue (about $800,000) have remained fairly stable over the last three years, according to an e-mail from Jeff Butteris, manager of the economic development division. Nonetheless, "the future remains somewhat clouded," he said, because of staff reductions and local funding challenges due in part to the financial condition of the state of Wisconsin.

And then there's the competition, the undeniable sign that there is a market for customized training. According to Butteris, "Anyone seeking education, skills training or professional development has more options than ever. My experience tells me that this arena becomes more crowded every day. We see national companies, both public and private universities, professional associations, local consultants, technical experts and increasing Web-based offerings in our district daily."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.