With a population of barely 1,000, the hamlet of Wessington Springs, S.D., might seem an odd place to find banking trends encapsulated and on display in the Ninth District.

Located in the eastern half of the state, Wessington Springs is a place a nonlocal would have to purposefully visit because it's not on the way to anywhere in particular. A person traveling from Mitchell north to Huron—big cities in a South Dakota sense—would have to hang a left onto Highway 34 and go some 20 miles out of the way to get to Wessington Springs.

But there you'll find the head office of American Bank & Trust, an agricultural bank with some $160 million in assets that is a microcosm of banking trends riffling through the district and nation, particularly in many rural areas.

Like a back country road, the history of American Bank is long, winding and interesting. It all started in 1888, with a bank of a different name—the Bank of Alpena—in the small town of Alpena, which lies about 20 miles to the northeast and today still has just 265 people.

By 1962, the Bank of Alpena had been profitable enough to twice build itself a new home in Alpena and also to open a new branch that year in nearby Wolsey, whose population today is 418. By this time, bank assets had crept to $50,000. Two years later, the parent bank was moved to Wessington Springs; the Alpena bank was turned into a branch office, and the bank name was changed to American State Bank. Assets grew quickly to $150,000. Bank ownership changed hands in 1972—and is still owned today by the Steele family—but the focus remained on serving local farmers and small businesses. By the mid-1980s, assets grew to some $20 million, according to Lynn Schneider, the bank's president and CEO.

Then in 1986, American State Bank bought a branch of First Bank (now U.S. Bank) in Wessington Springs, roughly doubling its assets. Seven years later, it acquired Farmers State Bank in Mellette (population 236). Then in 2000, it bought the Hand County State Bank of Miller—its biggest market yet at 1,530. By now, increasing business and the additional locations helped American grow to $100 million. When it opened a new branch in Huron in 2002—and changed its name to American Bank & Trust—the small, Steele family bank in some ways had come full circle, Schneider said.

It was in Huron that the Steele family owned its first bank, Farmers & Merchants, but later sold it to Marquette Bank. American decided to open a branch there decades later when that very Marquette branch had to be divested in order for regulators to approve a sale of Marquette Bank to Wells Fargo. American wasn't the buyer, "but it offered the opportunity to finally come back into Huron," said Schneider, whose office is located at the Huron branch.

What started well over a century ago as literally a one-horse town bank grew into a bank with six locations and assets of $160 million—with about 85 percent of that growth coming the last decade and a half. Schneider said the buy-and-branch activity was not a formally planned strategy.

"We don't have, as an organization, a strategy to get to a certain asset size," Schneider said. "We're not out there scouting out and hunting down opportunities" to buy and branch, he said. Rather, "we want to do a good job with what we've got and take advantage of opportunities" that make themselves known.

"It just seems like as you try to plan for and create a future for the bank, you look for where the growth is," Schneider said. That meant buying other agricultural banks in order to keep pace with the consolidation of farms (and their loan portfolios). The branch in Huron—easily the biggest city in the area at 12,000—has helped diversify the bank's portfolio, from about 75 percent agriculture to about 50 percent.

Schneider believed that banking consolidation was likely to continue, which brings added pressure for small banks, but also opportunities. "You could argue it's tougher and more challenging. ... [But] I suppose from a community bank sense of things, we've found quite a bit of opportunity even with consolidation going on."

A spark, then rapid-fire change

Oddly enough, the story of American Bank & Trust is not terribly unique—indeed, it's being repeated in some form rather regularly across the district. That's because banking has seen significant structural changes over the last two decades, the result of regulatory rollbacks in the late 1980s and early 1990s that relaxed geographic restrictions on where banks could do business.

Before 1970, no state in the nation allowed interstate (or multiple state) branching, and even intrastate branching (within a bank's home state) was limited. Interstate banking (ownership of chartered banks in multiple states) was also limited to those banks that were grandfathered by the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956.

In essence, prior to about 1980, the nation had 50 banking systems—a different one in each state. Some states, like South Dakota, were comparatively open to bank expansion. But others, including Montana, preferred so-called unit banking, where banks were often allowed no more than one full-service office, with virtually no branching.

But deregulation slowly opened the doors to bank expansion geographically and brought about major structural changes in the banking industry, both nationwide and in the Ninth District.

An analysis of the district's banking sector by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis showed the following major trends from 1990 to 2003:

- reduction in the number of head offices and unique banking firms with operations in the district, but ...

- substantially more branch office locations, producing a sizable net gain in the number of banking service points;

- a slightly greater presence by out-of-state banking firms;

- the pace of change in individual states coincides generally with how quickly (or tardily) each joined in the move to deregulate (see "Laws that giveth and taketh away"); and

- little difference in the structural trends between urban, fringe and rural banks (see "Banking trends in a county near you").

Out of many, one

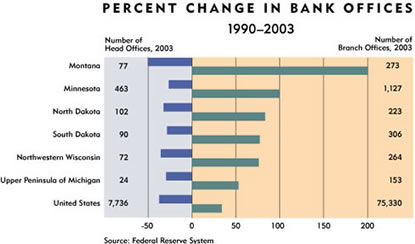

If you're not paying close attention, the casual observer might think that the banking industry is shrinking. From 1990 to 2003, the number of charters (or head offices) located in the district fell by 31 percent—somewhat slower than the national rate of 37 percent. All district states saw the same general rate of decline with the exception of Montana, where charters were sliced in half during this period (see chart).

In years past, a drop in the number of banks could well have meant that some towns were losing service altogether because a local bank was failing. According to a 2004 report by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.(FDIC), bank failures stemming from a bad farm economy and the savings and loan debacle were a significant contributor to falling bank numbers in the mid-1980s and early 1990s. From 1987 to 1991, an average of 388 banks failed every year.

Since then, however, failures have been virtually nonexistent. From 1994 to 2003, a total of 66 institutions failed nationwide. Rather, falling bank numbers are the result of widespread consolidation, where banks are being acquired by or merged with another bank under the expectation that the new whole is more competitive (and therefore more profitable) than its previous parts.

Minnesota, for example, has had just two failures among state-chartered banks since 1990 and another two that were voluntarily liquidated, compared to 78 state charters that have been canceled due to mergers, according to Mary Jo Wall of the Minnesota Department of Commerce. In the great majority of cases, a canceled charter simply means a former head office has become a branch to its new owner.

Most of the attention regarding consolidation is with activity at the top of the food chain—the big banks. In 1998, Minneapolis-based Norwest acquired Wells Fargo (and decided it liked that name better), creating the seventh largest banking company in the United States (and this after more than 100 other acquisitions by Norwest). Three years later, Minneapolis-based U.S. Bancorp was bought by Firstar Corp. of Milwaukee for $21 billion in stock (but got to keep its name).

Though considerably smaller in national scope, one of North Dakota's biggest banks became an acquisition target this year when Community First Bankshares, the parent company of the 155-branch Community First National Bank in Fargo, N.D., was purchased for $1.2 billion by BancWest Corp., a subsidiary of one of Europe's largest banks (BNP Paribas).

Conventional wisdom on the consolidation topic implies that the big fish are also eating all the little fish. That is happening. From 1994 to 2003, almost three-fourths of all merger targets had assets of less than $250 million, according to a recent report on mergers by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. One simple reason for this is that there are more—many more—small banks to be acquired in the first place. According to FDIC figures, about three-quarters of the nation's 7,700-odd commercial banks have less than $250 million in assets.

But the consolidation trend is more accurately described as all fish eating each other. Blockbuster mergers have grabbed a lot of newsprint, but beneath that watermark is a lot of merger activity among smaller banks. The Fed report found that slightly more than one in five mergers and acquisitions in the last decade involved one small bank (less than $250 million in assets) swallowing another small bank; an additional 12 percent of mergers were by banks with $250 million to $500 million buying smaller peers.

Small banks typically acquire other small, in-state banks—often located nearby—to diversify their loan portfolios and increase economies of scale to spread out the costs for new technology and other investments, as well as for regulatory compliance.

"The small rural bank in a no-growth or declining market often looks to neighboring towns for acquisition potential or branching," according to Gary Geiger, via e-mail. Geiger is the president and CEO of Heritage Bank, which has three locations in and around Willmar, Minn., about 100 miles west of the Twin Cities. He is also the current chairman of the Minnesota Bankers Association. "The more complex the banking business becomes, the more difficult it is to be a small bank. Growth is necessary to justify staying in business. The only solution is to grow or sell out."

About one year ago, for example, Citizens State Bank of Arlington, S.D., (pop. 992) bought nearby First State Bank in Sinai, a dot of a community with 120 people located 12 miles down the road in the eastern part of the state.

"We had like customers in like areas. We're both long-term community banks," said Robert Rutten, president of Citizens State Bank. He's not exaggerating either. Citizens opened its doors 103 years ago, and First State followed seven years later. As neighboring agricultural banks, they historically considered each other competitors. But in June 2002, First State took its $18 million in assets and approached Citizens, with $46 million.

Rutten said Citizens was a very willing buyer because the acquisition was not done out of desperation for either bank. "They [First State Bank] didn't have to sell. They were a good bank. ... They were making good money," Rutten said. But First State Bank was small enough that it didn't have the size and technology to compete over the long run. So First State went looking for a suitor to fill those gaps and still allow it to provide the same type and level of bank service to its long-time customers.

"It was a good opportunity ... [and] a good fit for us," Rutten said. "We looked at it for the loans." Importantly, First State had five long-time staffers who were retained, which meant the sign changed out front, but not much else did after the acquisition was completed. "They are a part of us, but they are doing business with their customers like they were before."

Fewer trees, bigger canopy of branches

While consolidation is cutting down on the total number of firms vying for the clients' wallet, don't fret just yet for the banking customer. Studies to date suggest that bank markets are still far from exhibiting classic monopoly or market power; if anything, local banking markets are more competitive because deregulation has made it easier to expand geographically.

Nowhere is that more obvious than in branching, where a major expansion has taken place. From 1990 to 2003, branch offices in the district more than doubled to about 2,400. As with head offices, the increase in branches was roughly comparable across the district with the exception of Montana, where the rate of branch formation was substantially faster (see chart).

Some of this rapid increase in branches is merger-induced, as head offices are converted into branches. But more than two-thirds of the additional branches added since 1990 represent new offices. As a result, the total number of bank "service points" (defined as both branch and head office locations) increased 36 percent to more than 3,200, according to Minneapolis Fed analysis.

Nationally, these banking trends have been more muted. Branches, for instance, rose just 34 percent since 1990 to about 75,000, and total banking service points grew only 24 percent. States with the greatest branching activity were those where relaxation of branching laws occurred later—like Montana, Texas and Wyoming, all of which had branching restrictions until the late 1980s.

In fact, not every state has seen strong branching growth over the last decade, and branches have actually dropped in 10 states, particularly major bank states like North Carolina and California. These states generally had minimal branching restrictions to begin with or relaxed them earlier than other states, and mergers helped consolidate not only head offices but also branches.

Not long ago, experts were predicting just such a trend nationwide for brick-and-mortar branches, thanks to "teller-less" transactions of ATMs and telephone and online banking, where marginal costs run close to zero. Though transactions from each of these technologies continue to grow, none has supplanted the need for face-to-face contact with customers. For one, customers demand it. Surveys of consumer preference by the Federal Reserve Board show that people like being close to a bank; proximity is the single most important factor in a person's choice of bank. But banks also benefit from direct contact, because a new product tends to catch on better when it's pitched face-to-face rather than via the Internet, phone or ATM.

Said one North Dakota banker, "Some get tied up in the minutiae of branching. What is really being tried isn't a new branch, but a way to reach a new clientele."

The development of less-expensive branches also makes it easier for the head office to expand to new markets. Several bankers noted that the majority of bank operating costs are for personnel, and capital costs are a small (and dropping) percentage of total costs as banks are doing fewer stand-alone buildings. A branch opened 20 years ago might require a staff of 12 to 15. But a so-called convenience branch opened today-like those you see in grocery stores and other high-traffic retail outlets-can be as small as 1,200 square feet and demand the equivalent of just three or four full-time staff. So with more branches, said a Sioux Falls, S.D., banker, "you're providing more customer service locations without the additional cost of [traditional] banks."

It's a phenomenon similar to the explosion of ubiquitous ATM machines. Though the number of ATM transactions is growing, the number of ATM machines is likely growing faster still for the simple fact that the cost of the machine has plummeted—from about $50,000 to about $7,000—making it more attractive to add new locations to improve customer convenience. As a bank adds ATMs, it experiences what's known as the network effect—the more it has, the more valuable each existing ATM becomes.

And then there was one?

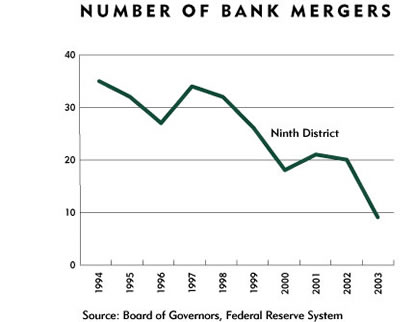

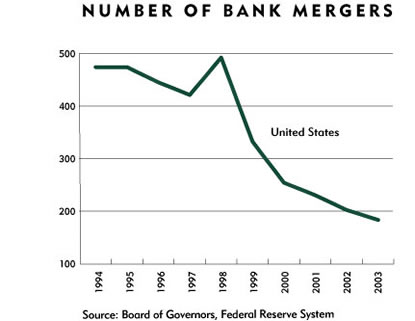

Where these trends are heading is open to much speculation. There is some evidence that consolidation might actually be slowing. The number of mergers nationwide has steadily declined since 1998, dropping from almost 500 to 184 in 2003, according the Board of Governors study this year on bank mergers. In district states, there were 32 mergers in 1998. In 2003, there were just nine.

The 2004 report by the FDIC—one of several on the future of banking—took a close look at consolidation data and "found that the rate of decline in the number of banking organizations appears to be slowing markedly," and if the recent past was any indication, "the current rate of decline can be expected to slow even more over the next five-year period."

The report noted that "the major influences of the 1980s, under which the decline accelerated, are no longer relevant. Gone are the high failure rates and contractionary influences of the thrift and banking crises. Similarly, the effects of liberalization of interstate banking and branching laws are largely in the past, as are the effects of most other major regulatory initiatives." With such forces having run their course, it suggested that current trends "might presage a return to a relatively stable population of banking organizations."

Not everyone's quite ready to believe that the banking foot is coming off the consolidation pedal. Consolidation and branching can tend to be self-reinforcing trends, working in combination to increase competition, which in turn induces more consolidation and the desire to branch for more growth. In an informal e-mail poll of district bankers, more than one banker noted that consolidation and branching forced banks to "sharpen their pencil," and most see branching and mergers as a competitive strategy going forward.

Said one North Dakota banker, "I don't think there is any question that these trends will continue. Economics will force the issue."

Several other bankers mentioned that economics would play a role in the consolidation trend, but not always a role of hardship. Banking was still very profitable, even for small banks, according to Bill Partain, president and CEO of First National Bank in Missoula, Mont., and president of the Montana Independent Bankers.

In a phone interview, Partain said that Montana banks "are actually doing better than average" in terms of return on assets and equity. (In fact, FDIC data on the first quarter of 2004 showed that insured institutions headquartered in Montana reported median pretax returns on assets that were 20 percent higher than the national median.) As a result, he said, "it's still kind of a seller's market," and some community banks "have stars in their eyes" regarding a possible buyout from a bigger bank.

Partain and other bankers also pointed out that further consolidation was likely because of poor succession planning among what Partain called "owner-occupied banks"—those in small towns with older, local ownership. Over the next five to seven years, Partain said, "there will be some sales" among small banks simply because there is no family bloodline to continue that bank's ownership.

And similar to trends of the last decade, even those banks "lost" to a buyout or merger will likely remain in business, in one form or another.

Rutten, from Citizens State Bank in Arlington, is also on the board of directors for the South Dakota Bankers Association. One mission of the organization "is to keep [local] banks in South Dakota," he said, which meant that more mergers or acquisitions were likely between neighboring community banks—banks that previously saw each other as major competitors—"instead of selling out to the big bank."

That's just what happened when his own bank bought First State Bank in nearby Sinai. "It's a viable branch serving a small community in rural South Dakota," Rutten said. The buyout "let them continue to be a bank, and [customers] still have local bankers taking care of them."

Related articles: |

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.