In small towns and in farm country, many people get by with what might best be called unconventional access to pharmacy services. Residents in one small town in Montana were getting their medications with eggs over-easy.

In small towns and in farm country, many people get by with what might best be called unconventional access to pharmacy services. Residents in one small town in Montana were getting their medications with eggs over-easy.

In Valier, an isolated town of about 500 in northwestern Montana, many residents had their prescriptions filled by a pharmacist in Conrad, a city of 2,700 about 30 miles southeast of Valier. In an effort to save people the hour-long round trip, the Conrad pharmacist would package all prescriptions for residents around the Valier region and have them delivered by a rancher if he were conveniently heading that way.

The drop-off spot? The Panther Café, where one of the waitresses handed out the medications because she "knew everyone and everyone's children," according to Nancy Dunagan with the Montana Board of Pharmacy. "Obviously, that was not an acceptable means of delivery for the board," because it compromised issues of patient privacy as well as medication security and safety—changes in temperature can compromise some medications.

So the Board of Pharmacy held an open meeting with the townspeople, and "we came up with an alterative method that satisfied the townsfolk and the compliance specialist" and included a temperature-controlled, security-code delivery bag. Prescriptions still went to the café, but had to be picked up on a signature system, Dunagan said. That unconventional, do-what-it-takes mentality "is pretty much how it still works in rural Montana."

Elsewhere too, it seems. According to meeting minutes, the South Dakota Board of Pharmacy has become concerned about reports that pharmacies there were allowing patients to pick up medications at sites other than registered pharmacies.

Access to basic consumer goods and services has long been an overriding concern in rural areas. But access to prescription drugs is particularly sensitive because it relates so closely to people's health and quality of life. The question of access has a lot of immediacy now because an aging population—especially in rural areas—is needing and demanding more prescription medication, and a new Medicare drug benefit is just now kicking in to subsidize it. The traditional pharmacy is getting squeezed hard by third-party payer systems (see related article) and other trends, and many small-town pharmacies are struggling to stay open.

But that doesn't mean access is being compromised. Technology and process innovations have created new methods and places to have prescriptions filled. The downside is that these same innovations compound the competitive pressure already on traditional retail pharmacies. The upside, along with improved choice, is that some innovations could potentially relieve some of the most chronic problems facing rural and independent pharmacies.

Road trip to the pharmacy

As in the Valier example, the definition of access depends on your station in life, and where your station is located.

The public debate over access generally focuses on geographic proximity. By that measure, access to pharmacy services has always been a struggle in rural areas. For example, there are about 230 retail pharmacies in Montana, the majority bunched up near the state's bigger cities. A total of 10 counties have no retail pharmacy, and another 17 have just one.

When a rural area loses a pharmacy, there's no guarantee of a replacement. A 2001 report by University of Minnesota researchers tracked pharmacy closings in Minnesota and the Dakotas from 1996 to 1999. They uncovered 39 rural retail closings, 10 of which resulted in a community losing its only retail pharmacy, including three communities whose next closest pharmacy was 20 miles away.

Despite such closings, a follow-up study by the Minnesota researchers found that just 7 percent of rural residents lived more than 20 miles from the nearest pharmacy and only 1 percent was more than 30 miles away (though measured "as the crow flies" rather than by road miles). Rural pharmacists were also surveyed, and 75 percent disagreed that there were geographic barriers to pharmacy services in their area.

Indeed, many believe the biggest problem regarding access is not geographic, but financial. The University of Minnesota follow-up report identified 53 communities facing potential access problems. The authors contacted medical, social service and public health professionals in these communities. Sources noted geographic difficulty, but said "transportation barriers to pharmacy care are less important to the rural elderly than financial ones" because high costs prevented the elderly from having a prescription filled in the first place.

You've got mail

Technology is also providing new ways of having prescriptions filled that remove proximity from the access equation. In a radical move that appears to have grabbed more headlines than prescriptions, Minnesota and Wisconsin launched Web sites authorizing residents to purchase prescription medication over the Internet from pharmacies in Canada (and in the case of Minnesota, the United Kingdom as well), where drug prices tend to be considerably lower.

High drug bills are also forcing health plan sponsors (mostly employers and government) to seek out and experiment with lower-cost alternatives. One of the simplest changes to prescription fulfillment—and also the most unnerving change for traditional pharmacies—is mail order.

In terms of total prescriptions, mail order has risen from 5 percent in 2001 to 6.6 percent by September 2005, according to IMS Health, a healthcare research and marketing firm. That might seem small, but mail order prescriptions rose 16 percent last year. This delivery channel also captures a disproportionately large share of total prescription revenue—almost 15 percent last year, compared with less than 12 percent in 2001—because most prescriptions are for larger, 90-day drug orders.

That has pharmacy owners looking over their shoulder. A 2002 University of Minnesota study found that almost one-fifth of rural pharmacies saw mail order pharmacies as their biggest threat, particularly as more health plans move to mandatory mail order for certain kinds of so-called maintenance drugs that are taken regularly to help people manage chronic conditions like high cholesterol, arthritis or heart disease.

In Montana, pharmacists have to deal with the fact that the state's largest employer—the state government itself, including university employees—mandates mail order for maintenance prescriptions, according to Paul Wolfgram, a Montana pharmacist who owns pharmacies in Butte, Townsend and White Sulphur Springs. Responding by e-mail, he said. "Mail order is a potent threat to all pharmacies in this state, especially those in more rural areas."

Though mail order outlets abound—the state of Montana issued some 275 mail order licenses last year, up from 46 in 1997—the large majority of mail order prescriptions come from a small handful of large, sophisticated operations owned by insurance and health benefits companies. For example, a quarter of a million prescriptions get filled via mail order every month from Cigna Tel-Drug, a mail order pharmacy in Sioux Falls, S.D., and affiliate of Cigna, a nationwide provider of employer-based health and related benefits.

As chief operating officer of Cigna Pharmacy Management, Tom Greenebaum oversees Tel-Drug as part of Cigna's pharmacy network development. He said Tel-Drug was created when Cigna bought out a small, family-owned firm located near Sioux Falls that was filling about 10,000 prescriptions a month. Volume grew thanks to the steady stream of prescriptions from people in Cigna-covered health plans. But the firm started seeing "significant growth" in 2002 when Cigna started providing more incentives for enrollees to use mail order.

According to Greenebaum, mail order pharmacy capitalizes on a couple of competitive traits. Automation has brought both higher fill accuracy and lower costs, and users find it convenient. In busy households, "it's easier to go to the Internet and click a button and have that (medication) delivered to your door," Greenebaum said.

Tel-Drug also offers perks to those on the other side of the counter. With 55 pharmacists, Tel-Drug has the largest concentration of pharmacists in the state. Yet Greenebaum said that firm doesn't have difficulty finding new or replacement pharmacists when it needs them, mostly because "we offer a lifestyle difference. We have nine-to-five hours. You're not on call. You can take lunches and breaks. There's no 12-hour shift, and you're not working weekends and holidays."

Yes, but

The pharmacy industry appears to grudgingly accept the reality of mail order. "There's a niche in all this for mail order," said Jim Smith, executive director of the Montana Pharmacy Association. "We fought the battle and you might say lost."

But Smith and others in the traditional pharmacy industry complain that mail order pharmacies benefit tremendously "because of the unlevel playing field" created by the health insurance industry. Maybe ironically, few major mail order firms are owned by pharmacies. Instead, the largest mail order pharmacies are owned by health companies (like Cigna) as part of a vertical integration strategy that's looking to do two things: capture part of a rapidly growing healthcare market (namely, prescription drug spending), and keep prescription drug costs down for other segments of the business chain (in this case, drug coverage claims).

According to Smith, an insurer's health plan will often provide incentives—like lower deductibles and co-pays, and the ability to receive 90-day refills—for health plan enrollees to use mail order and essentially penalize them if they still choose to use the local pharmacy. Few prescription benefit plans even give brick-and-mortar pharmacies the chance to fill 90-day prescriptions, a staple for mail order pharmacies.

Greenebaum, from Tel-Drug, pointed out that insurers go to employers with multiple plans to choose from, and the structure of any prescription benefit is ultimately the choice and responsibility of the employer, who is looking to keep costs as low as possible. "Our (prescription benefit) plan designs are based on what the client wants. … It's an employer-driven decision. … Our goal is to get to the lowest net cost for our client" while still providing coverage the client desires. Employers pay less for prescription benefits if members choose cheaper options, "so they incent members to go to mail order."

Smith rebutted: "I believe it would be technically true to say that employers ultimately make these choices. But … they are guided by their (pharmacy benefit manager), which usually has a mail order component. The range of options presented to employers is developed by the PBMs. Everything is couched in terms of the PBM saving the employer money, (and) 'mail order equals money saved' is the overly simple calculus presented to employers." He noted that surveys demonstrate "pretty well that customers would rather trade at their hometown community pharmacy, but the economics really discourage them from doing that."

Ken Nelson is the owner of Luck Pharmacy, located in the city of the same name in northwestern Wisconsin. He noted that PBMs originally existed simply to administer the prescription plan for employers. "Now they wish to administer and provide, which is a tremendous conflict of interest," Nelson said via e-mail. "If a PBM wanted, they could allow all community pharmacies the ability to dispense a 90-day supply, but they realize that their mail order service would suffer."

Some PBMs will offer contracts allowing retail pharmacies to fill 90-day prescriptions, but at a reimbursement rate that "does not cover the cost of the medication and, thus, the community pharmacy has to decline," Nelson said. "This is exactly what the PBMs want to protect their mail orders."

It might not be quite that simple. Automation and buying leverage with drug manufacturers allow most PBM-owned, mail order pharmacies to fill prescriptions more cheaply, which means they can be profitable at a lower reimbursement rate than traditional pharmacies.

Some new pricing options are being tested, including having the beneficiary pay the difference for filling a prescription at a higher-cost location. But that also adds complexity and confusion to a benefits program, not to mention higher out-of-pocket costs for the beneficiary—not exactly strong selling points.

Pharmacists hotly dispute the notion that mail order saves money.

An article last year in the peer-reviewed Journal of the American Pharmacists Association argued that while mail order pharmacy was less expensive overall, including to the patient, it was more expensive to the plan sponsor (and payer) because the loss of co-payments on larger-sized prescriptions "was greater than the savings on ingredient costs and dispensing fees." A pilot drug plan by MedImpact, a PBM, found that 90-day maintenance prescriptions can be cost-effective through a retail pharmacy and give enrollees the choice of where to fill the prescription. Notably, however, MedImpact does not own a mail order pharmacy—which, ironically, could be an argument used by both sides.

Most available evidence, however, shows that mail order is cheaper than traditional retail. For example, industry figures suggest that the mail order dispensing costs can run as low as $2.50 per prescription, well below the cost at community pharmacies. A 2003 Government Accountability Office report on federal prescription health benefit programs found that for a small drug basket (14 name-brand, four generic) of 30-day prescriptions, the average mail order price was about 10 percent less than the price within the PBM's retail pharmacy network.

A widely cited study published this past summer by the Lewin Group (and commissioned by the Pharmacy Care Management Association, which represents the country's major PBMs), found that mail order pharmacy represented a 10 percent cost savings over community pharmacy. The report acknowledged the differing size of typical mail order and retail prescriptions, but said, "There is strong evidence that the greater efficiencies of automation and workflow inherent in the structure of mail-service pharmacies enable them to produce cost savings well beyond those associated with the larger-days supply."

The controversy surrounding mail order has even gotten the attention of Congress, which asked the Federal Trade Commission to look at pricing and so-called self-dealing—profiteering by PBMs funneling business to their mail order pharmacies.

The FTC gathered data on prices, generic substitution, dispensing rates and other practices. It its final report late last summer, the FTC concluded, "These data provide strong evidence that in 2002 and 2003, PBMs' ownership of mail order pharmacies generally did not disadvantage plan sponsors." Specifically, the report noted that mail order prices were lower than retail prices for a "common basket" of same-sized prescriptions dispensed in December 2003, mostly because PBMs "obtained larger discounts off the same reference drug price for prescriptions dispensed at mail than at retail."

In part because of documented savings for plan sponsors, the report said complaints of self-dealing were "without merit." However, given the aggregate nature of the data, the report could not answer whether individual plan sponsors negotiated the best deal possible, or whether a PBM might have favored its mail order pharmacy "in ways contrary to a plan sponsor's interests." Still, the report argued, there was enough competition in this sector for employers and other plan sponsors "to safeguard their interests."

Reality TV

While the competitive pressures for traditional pharmacies might seem insurmountable, technology can also help rural areas retain some semblance of traditional pharmacy services.

Specifically, pharmacists are using telecommunications to give underserved areas the next best thing to a pharmacist: a virtual one. Telepharmacy, as it's called, uses state-of-the-art telecommunications so pharmacists can do what they do without actually being there: review prescriptions, double-check fill accuracy and consult with patients about drug interactions and other health matters. An on-site pharmacy technician handles all other tasks for filling a prescription.

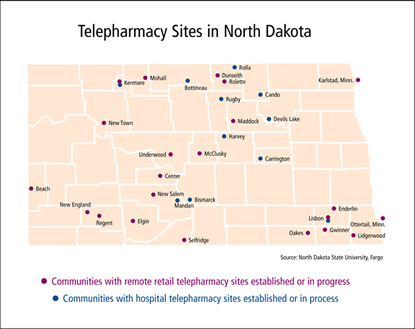

Still in its infancy across the country, the concept has been bear-hugged by North Dakota and offers a glimpse into a possible future for pharmacies, particularly in rural areas. North Dakota was the first state to allow full-service prescription filling at a pharmacy that did not have a pharmacist physically on the premises—a major obstacle, one that North Dakota managed to hurdle while most other states have decided to take a wait-and-see approach.

An estimated 200 locations in the United States use telepharmacy. One-fourth of them are in North Dakota: 33 remote sites where the only pharmacist you see is on a closed-circuit TV and 17 central hubs where the "live" pharmacist works. The state estimates that 40,000 rural citizens have had their pharmacy services restored, retained or established through telepharmacy. The average remote site is about 50 miles from the central pharmacy site, dispenses an average of just 35 prescriptions daily and serves communities ranging from 500 to 1,400 people.

The initiative got kick-started a half-dozen years ago when a state Board of Pharmacy survey revealed that 26 communities in the state had lost their pharmacy service "within the fairly recent past" and another dozen were at risk of following the same path, according to Ann Rathke, coordinator of the telepharmacy program, which is housed at the College of Pharmacy at North Dakota State University.

Rathke said officials with the state pharmacists association, state board and pharmacy school "put their heads together … (and) said, 'Why can't we put a (pharmacy) tech out there'" to fill prescriptions and use technology for an off-site pharmacist to supervise, screen prescriptions and counsel patients.

That proposal met with some initial opposition, as pharmacists believed that patient care might be compromised without a pharmacist on-site. "Some pharmacists don't want to let go of that control," Rathke said. But the state Board of Pharmacy developed the legislation—and with it, the necessary safeguards—to help state pharmacists buy into the idea, she said.

The effort got some big boosts along the way, probably none more important than a steady stream of grant money from the federal Office for the Advancement of Telehealth. Rathke said OAT grants helped pay the start-up costs—hardware, software, connectivity, sometimes even operational/salary money—for each site currently in operation.

There are projects currently in the development stage that will bring telepharmacy services to five new remote sites in North Dakota. No other district state has given telepharmacy more than a token effort so far. Montana is doing a telepharmacy pilot right now in Harlowton, a small town of 1,000 people smack in the middle of the state.

A high-level source in Minnesota called telepharmacy "a fall back, less-than-desirable method to having a real pharmacist." Rathke didn't disagree with that notion, but said the telepharmacy model is closer to the real thing than most imagine.

"There is face-to-face interaction. You're not looking at that person across the counter, but (instead) in real time on a TV set," Rathke said. "It really is pharmacy as usual, just not face-to-face in the same room." Some patients have reported uneasiness with telepharmacy, most of which disappears after a visit or two, she said.

Can you hear me now?

Given its rural predisposition, telepharmacy seems to have limited applications. In fact, the opposite might be true. For starters, literally hundreds of tiny towns just in the district could hypothetically benefit from this model.

Naysayers also fail to see the broader trend in telehealth. Rathke pointed out that personalized medical services like mental health consultations are being done remotely with similar technology. By comparison, the patient interaction required with telepharmacy is far simpler, she said. "I can certainly hear what to do with my prescription."

Maybe unknowingly, the telepharmacy model has uncovered opportunities for pharmacy expansion well beyond the social-good intentions of retaining and restoring service to underserved areas. Rathke said word is getting out among pharmacists that telepharmacy offers an opportunity to expand their rural practices—something almost unheard of previously.

And there just might be an economic rationale for it as well. Despite low prescription volume, officials note that the telepharmacy model is profitable. That's due in part to the OAT grants, but Rathke believed telepharmacy would be moving ahead—albeit more slowly—even without the federal incentive. "There would be pharmacists going ahead without it. It's a great concept. … The need is there," she said. "The grant money has increased the motivation for it."

Already, the state has lifted the telepharmacy ceiling, allowing a single pharmacy to operate four remote sites. Some pharmacies, including the Thrifty White chain, based in Maple Grove, Minn., are looking at a concept called "central telepharmacy," where a designated pharmacist oversees the operations and order-filling for multiple remote sites exclusively, rather than splitting time supervising a remote site and one traditional pharmacy.

Indeed, if pharmacists and patients become more accustomed to this delivery model and telepharmacy proves to be profitable, it's not a stretch to imagine telepharmacy as an expansion model—allowing pharmacists to open new branches and bring more competition to the urban and rural pharmacy markets.

Officials emphasized that was not the intent of the telepharmacy program in North Dakota. "It was not intended as a mechanism to add one more pharmacy to an already flooded marketplace in a large urban area so that large corporations could monopolize and capture a greater market share," said Charles Peterson, dean of the College of Pharmacy, who corresponded at length on the topic via e-mail.

At the same time, Peterson acknowledged that after demonstrating its utility, telepharmacy might not fit neatly back into the genie bottle. But, he pointed out, "The state boards of pharmacy have full authority and control over whether it occurs and where it is appropriate or not appropriate, where it should be allowed, and what restrictions if any are necessary. Each state needs to make its own decision on this matter regarding where it best fits in serving the state needs."

To that end, Peterson said the success of the program also has opened his eyes to the potential for addressing other entrenched problems faced by community pharmacies. For example, finding relief pharmacists to fill in for those who are sick or on vacation is "one of the biggest problems facing rural community practices—and small rural hospitals for that matter. … They literally cannot take time off of work because they cannot find relief help."

Telepharmacy could change all that. Peterson said it could help create a network of connected pharmacies, "which will allow the pharmacist-in-charge at any of these locations to be gone from their store for whatever reason … (and be) covered by another pharmacist from a different store, in a different community." Such a setup could be particularly useful for chain pharmacies "when a pharmacist at one of their store locations suddenly calls in sick or they have a workforce shortage somewhere," he said.

Not only would that free up the schedules of pharmacists, but it would also allow individual stores to expand hours into evenings and weekends without adding pharmacists to the payroll. The new-found freedom and a better business model offered by telepharmacy "also makes it more attractive and easier for pharmacist store owners to sell their stores to someone else if this option is available," Peterson said.

In fact, Peterson said, this is already being done in North Dakota, including linkages between 12 small rural hospitals "so that the pharmacists at these locations could provide cross-coverage for each other on evenings, weekends and on-call and not have pharmacists subject to job burnout. … It has worked very well so far."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.