The federal government is often caricatured as a black hole where tax money goes to die. It might be better described as a flying sieve, pouring money received from taxpayers across the United States back into states to pay for many programs and other obligations.

Though tax policy receives a lot of attention, where that federal spending actually lands receives much less mention. Does it matter? Well, the federal government spent some $80 billion in direct expenditures in 2004 in five district states combined. While many people and states have the impression that they pay the government more than they receive in benefits, the cold, numerical truth is that some people and states are recipients of more—sometimes much more—federal spending than others.

Every year, the federal government puts out a Consolidated Federal Funds Report that details how and where federal money is spent, including grants and payments to state and local governments, salaries and wages of federal employees, government procurement awards, federal insurance programs, and transfer and other direct payments to individuals. In all, the CFFR tracks spending in 33 federal departments and agencies, including some 600 federal assistance programs and 1,500 programs overall.

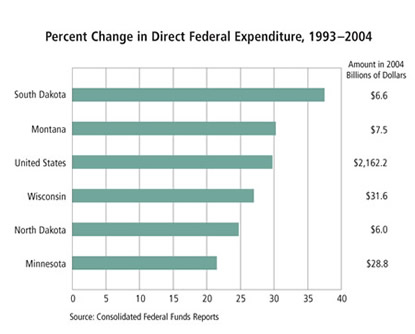

The sheer volume of programs is likely one of the reasons that federal spending expanded rapidly from 1993 to 2004. In nominal dollars, federal spending in every district state has trundled steadily higher. Even adjusted for inflation, total federal spending rose by 30 percent. Two states in the Ninth District—Montana and South Dakota—fared as well as or better than the national average, while federal spending growth was slowest in Minnesota (see chart).

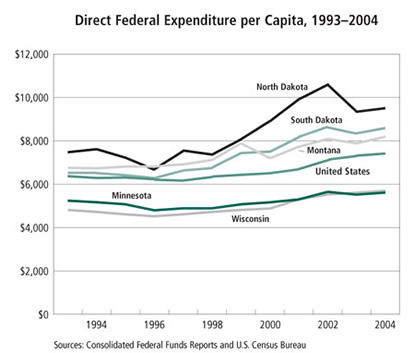

Federal spending on a per capita basis has something of a magnifying effect on the overall trend: While Wisconsin and Minnesota consistently lag the national average over time, the Dakotas and Montana show strong growth in federal expenditures on a population basis-North Dakota in particular, thanks to a rise in federal expenditures to the state while its population actually declined from 1993 to 2004 (see chart).

Looking for a transfer

So, where does all that federal money come from? Many people might imagine a smoke-filled back room, where politicians dole out pork to congressional districts. But the large majority of annual federal spending never sees the inside of a conference room. Most federal spending, not to mention most of the increase in federal spending in the Ninth District and the United States, sprouts from programs already in place.

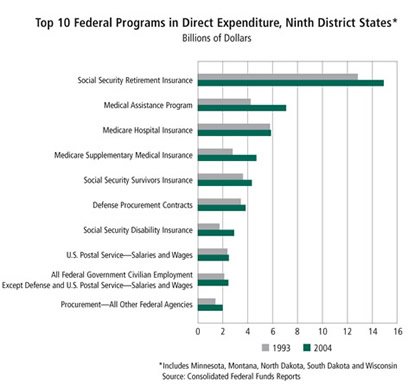

There are 10 programs or categories with $2 billion or more in direct expenditures in five district states combined and 16 categories with $1 billion. Together, the top 10 categories (out of 1,500 programs) were responsible for better than 60 percent of all federal expenditures in Ninth District states, ranging among individual district states from 55 percent in South Dakota to 69 percent in Wisconsin. These top expenditure programs saw a somewhat slower rate of real spending growth (25 percent) in the district compared with growth in all federal expenditures, but that hides a lot of variation among the biggest programs (see chart).

Social Security (in its various programs targeting various beneficiaries) is far and away the biggest source of spending in the district, totaling better than $22 billion in transfer payments in 2004 alone. Add Medicare—the federal health care program for seniors—and there's another $10 billion in federal benefits just for seniors in the district.

The state of spending

For the most part, this list of top expenditure categories holds for individual district states as well, but there are some interesting variations. For example, unemployment compensation benefits sneaked into the top 10 federal spending categories in Minnesota and Wisconsin, likely reflecting the fact that unemployment levels at the time were mostly higher there compared with the Dakotas and Montana, and higher average wages also meant federal benefit levels were higher.

Some states saw faster growth in certain big-spending programs. For example, total defense spending (which includes procurement and other military costs not reflected in the chart on page 15) rose steeply in most district states—between 60 percent and 100 percent in Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wisconsin (in nominal dollars). But in Minnesota, it rose just 10 percent over the same period.

The biggest difference in top categories among district states seems to have come out of left field—or more accurately, the corn field. Crop insurance payments made up a big chunk of the federal expenditures in the Dakotas, mostly because of the large presence of agriculture in the Dakota economy and the severity of crop failure in 2004 from drought and other disasters. That year, crop insurance payments jumped into the top five spending categories in both states, pumping $350 million into South Dakota and $440 million into North Dakota. These figures also don't account for implicit federal subsidies that lower a farmer's insurance premiums, an incidental effect worth $193 million and $147 million in North and South Dakota, respectively, that year, according to the federal Risk Management Agency, which runs the crop insurance program.

On net

Is your state a bigger receiver or a bigger payer when it comes to federal spending? According to the Tax Foundation in Washington, D.C., Montana and the Dakotas are net recipients of federal spending—in other words, they receive more in federal expenditures than state taxpayers pay in federal taxes. Minnesota and Wisconsin, on the other hand, are net payers; Minnesota in particular has been a big net contributor to Washington and, in turn, to federal spending in other states. That's due, in part to the fact that Minnesota and Wisconsin have higher average incomes, triggering higher federal taxation, which fueled high taxation levels in the late 1990s as both states' economies were performing at a high level. At the same time, states with lower average incomes (like the Dakotas and Montana) also come in line for more assistance, and that assistance tends to have an outsized presence in states with small populations.

Maybe the central message here is be careful what you wish for. Since the recession in 2001, the annual net returns in federal spending are closer to break-even for both Minnesota and Wisconsin. That's because federal tax collections in both states have been somewhat stagnant—the result of slower-growing state economies—while federal program spending to those two states has increased.

See additional data on federal expenditures in Ninth District states.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.