Every year, elected representatives go to Washington and engage in the drawn-out political process of passing a federal budget, funding the seemingly innumerable departments and agencies and giving substance to even more bountiful expectations for federal government spending.

A byproduct of this grueling process is something the public loves to get, but hates to see: budget earmarks, popularly referred to as pork or pork barrel spending. Members of Congress use the budgeting process as an opportunity to carve out federal funds to pay for local projects and programs.

This is called bringing home the bacon; scholars refer to it as "distributive policy." Whatever the label, by custom and implicit expectation, it's part of what politicians are elected to do. The practice of earmarking is widespread and has grown dramatically over the past decade and a half, both nationwide and in the Ninth District. In fact, by some measures, district states are among the most successful in getting earmarks into the federal budget for projects ranging from bike paths and ballparks to high-tech defense research and rural water systems.

Recently, following a spate of political scandals, earmark reform has been the order of the day, and there are signs that the growth of earmarks has abated, at least for the moment. But the debate over the merits of earmarking continues. Some have sought to eliminate pork altogether. In Minnesota this past December, Republican Rep. John Kline made front-page news by foreswearing the practice. Days later his Democratic opponent, Stephen Sarvi, responded, "These projects are not extravagant or wasteful—and members of Congress who seek them in the interest of the people they represent … are doing their job."

In this fedgazette, we'll dissect the pig, and it can get messy, though maybe not in the way readers expect. Given the nature of scarce tax resources, economists have something to say about the efficiency (or lack thereof) inherent in this allocation process and its distributional impact. And because earmarking is inherently political, analyzing it will require the unique perspective of political economists.

Political pundits and watchdog groups tend to excoriate earmarking, calling it the "currency of corruption," and some of the common defenses of earmarking are dubious. Still, pork barrel spending does have both theoretical and practical merit and may serve a broader public purpose than can be evaluated with narrow cost-benefit analyses. As such, it cannot be wished away as easily as critics might hope. Unfortunately, there are no guidelines to suggest how much pork is good for fiscal health. Like most things, moderation is likely the utilitarian key to earmarks, but the trend line suggests that earmarking has become excessive.

Lend me your earmarks

Though they have distinct meanings, both "pork barrel" and "earmark" have their origin in the barnyard. Earmarks referred to notches or other markings made on animal ears to identify and denote ownership. Pork barrels were the brine-filled containers in which pork was stored before the days of refrigeration; granting access to the barrel was a means of distributing rewards to workers.

These days, of course, "pork barrel spending" is meant more figuratively as a government appropriation for a project or program that will benefit a legislator's constituents. And over the past decade, there's been a lot of benefiting going on, with earmarks funding a strikingly diverse array of programs and projects.

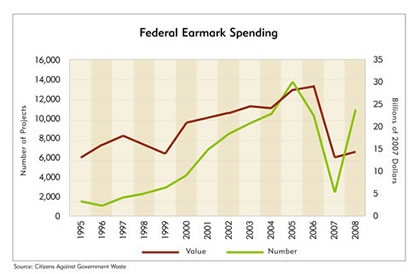

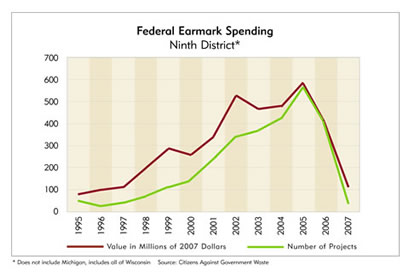

The number of earmarks nationwide rose almost 10-fold from 1995 to 2005, and annual earmark spending approached $30 billion (see chart 1) , before moderating in recent years (more on that later). That trend generally held across district states as well (see chart 2 and "This little piggy came home"), according to annual earmark data from Citizens Against Government Waste, a nonpartisan watchdog group that analyzes federal appropriations bills and identifies what it considers pork, according to several criteria. (While various agencies and groups use different standards and arrive at different figures, the CAGW data have the merit of consistent criteria over a considerable time period. (See sidebar.)

Chart 1

Chart 2

The executive branch and others have voiced displeasure over earmarks because they "circumvent" the normal federal appropriation channels: The president submits his budget proposal to Congress in February of each year, Congress holds hearings to question administration officials about their request, and the Senate and House budget committees then develop their own joint budget resolution, combining appropriation bills from 13 subcommittees in each chamber, to be passed by April 15 and then signed by the president. (It often takes longer; the budget for fiscal year 2008 wasn't passed until late December.)

Though it is not without flaws, this appropriation process acts as a proxy for what lawmakers believe to be the federal government's responsibility regarding the creation of certain public goods. Outside of, but running parallel to, this appropriation process, individual lawmakers insert earmarks into appropriation bills during the months of deliberation, usually with little attention paid to them. Rarely do they undergo the scrutiny common to a full-fledged executive agency budget item.

The controversy over earmarks has to do with the degree to which earmarks—individually and collectively—are legitimate and necessary public goods. The matter is complicated by the fact that there are no black or white boundaries, only gray areas. Opinions regarding the public utility of any single earmark tend to be geographically biased. Is $1 million too much for a Daschle Center for Public Service at South Dakota State University, which was approved last November to house the papers of the former, long-tenured senator? Certainly not to many South Dakotans. Folks in most other states—not to mention former members of Congress with no similar repositories—might disagree.

Drawing a dark fiscal line between federal, state and local responsibilities can be very difficult. Earmarks are famous for blurring that fiscal line, even rubbing it out altogether. For example, in 2005 the City of Tea, S.D., received $248,000 for costs associated with construction of a new city hall. A year later, Aberdeen, S.D., got $350,000 to convert an old high school into a recreational and cultural center.

South Dakota's not getting all the slop, so to speak. Communities in every state in the district, and surely the nation, have enjoyed similar federal windfalls that would appear to be very local public goods. Among the 6,000-plus earmarks packed into the 2005 transportation bill alone, the City of Virginia, Minn., received $1.3 million for a visitors' center on a regional trail for bikers and walkers; nearby Aurora got $236,000 to build extensions onto the same trail.

Pennies on the federal dollar

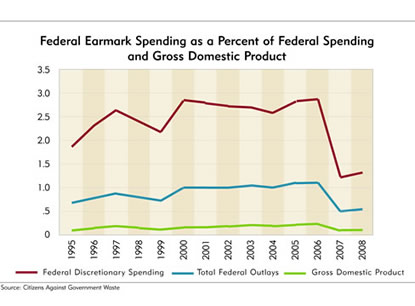

Some would have us believe that federal spending would be considerably lower were it not for earmarks. In fact, earmark spending is a small fraction of overall federal expenditures. CAGW figures show that at its peak, in 2006, pork accounted for just 1.1 percent of federal outlays and 0.22 percent of gross domestic product. But neither should those figures obfuscate the fact that earmarks as a percentage of outlays and GDP have risen considerably since 1995, before moderating of late (see chart).

Chart 3

An even better apples-to-apples comparison for earmarks would be with so-called discretionary federal spending, which is any spending controlled by the appropriation process. This eliminates spending governed by permanent laws, including such programs as Social Security and Medicare that do not require congressional approval, as well as interest payments on national debt. In effect, this compares pork to other spending for which lawmakers have some say-so.

Here, too, the percentage of earmark spending is pretty small, in the low single digits. But starting in the early 1990s, it rose steeply and steadily for about a decade, before tumbling in 2007 when earmark spending was rolled back. However, the "pork ratio" would have been much higher this decade had it not been for the War on Terror and a number of other emergency spending bills (like Katrina-related hurricane aid). Such emergency or supplemental spending has often piled on between $100 billion and $200 billion in annual discretionary outlays during most of this decade.

No matter how we slice it, or compare it, at $29 billion in 2006, total pork barrel spending ate up a lot of money. Public scrutiny and pressure have knocked earmark levels down considerably in recent years. But even at "just" $14 billion for fiscal year 2008, total spending on earmarks will exceed the discretionary outlays for entire federal departments, including Commerce, Interior, Labor and Treasury, and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Spoiled pork?

Also notable in the debate over pork is, well, the debate. As earmarks have increased, so have the attention and argumentative din concerning them. Congressional members rarely miss a chance to tell constituents about the federal spending they've managed to hog-tie for local benefit, communities celebrate the receipt of such money, and most everyone else seems to complain about federal spending running amok. Among the many critiques of pork, most imply that there are no good earmarks. There is little attempt to rationalize their utility in terms of what government is supposed to do: produce public goods.

It's easy to criticize earmarks when they go to private firms to produce what are essentially private goods—and some earmarks do little else. A small but controversial earmark slipped into the fiscal year 2008 omnibus appropriations bill by Montana representatives will help build a minor league baseball stadium in Billings, for example. And according to the Missoula Independent, a $2 million earmark supported by Sens. Max Baucus and Jon Tester will go this year to the Missoula-based Washington Corp. to develop "spiroid winglets" for more efficient fuel consumption by private jets.

Earmarks for production of public goods—national defense; infrastructure such as roads, bridges and national parks; health care; and public education—are far easier to justify. Public goods are often underproduced in market economies. But even when looking at government spending for public goods, economists will ask questions about the efficiency and distribution of earmarking.

For example, many view earmarks with the taint of corruption, that such spending is intended not to produce necessary public goods but rather to ensure the legislator's re-election. But some research suggests that earmarks have a functional role in the production of public goods, although there might be incentives to make earmarks inefficiently larger or more numerous than they need to be.

Underlying most economic analysis of pork barrel spending is public choice theory, a branch of economics that became widely known when James Buchanan, one of its founders, won the Nobel Prize in 1986. As the Nobel committee put it, Buchanan held that "individuals who behave selfishly in markets can hardly behave wholly altruistically in political life. This [perspective] results in analyses which indicate that political parties or authorities at least to some extent act out of self-interest."

Getting re-elected is, of course, high on the list of self-interests for most politicians, and it's from this vantage point that most political economists analyze the dynamics of pork barrel spending. In a classic 1981 paper in the Journal of Political Economy, Washington University economists Barry Weingast, Kenneth Shepsle and Christopher Johnsen used public choice theory to explain why politicians don't insist on economic efficiency.

They developed an economic model of public choice mechanisms comprising a representative legislature to explain "distributive or pork barrel projects," defined as projects whose benefits "are geographically concentrated and whose costs are spread through general taxation."

The economists first set a benchmark for efficient expenditure of taxpayer dollars and then compared that to results from a model in which legislators were elected by geographically defined districts but financed expenditures through taxes raised from the public at large. They found systematic bias toward inefficiently large projects. "The districting mechanism in conjunction with the taxation system provides incentives to increase project size beyond the efficient point by attenuating the relationship between beneficiaries and revenue sources."

Empirical tests

The Weingast, Shepsle and Johnsen model has been extended and tested by other political economists, and its basic findings seem to hold. Because pork barrel spending is paid for by general tax revenues, costs are externalized beyond the local area that benefits from the project, so the scale of the project is likely to grow.

"You start with that, with every individual legislator thinking, 'What can I bring home to show that I'm earning my keep, so you'll re-elect me?'" said Alison Del Rossi, an economist at St. Lawrence University whose empirical research has analyzed pork barrel spending (mostly on water projects) from the mid-1800s to the present. "So if you're deciding how big you want your flood control project, for example, you're going to choose based on the benefits to you, which are large and concentrated, and the costs that you have to bear, which are a very small fraction of the total because the costs are spread out over all congressional districts or states."

In a 1998 National Bureau of Economic Research paper, Del Rossi and Robert Inman provided the first direct empirical test of a central assumption in this theory, that legislators' requests for pork are price sensitive: They'll ask for more pork as their constituents' cost share declines and vice versa.

To test the assumption, Del Rossi and Inman examined an instance when legislators faced a price change after requesting local spending projects. The Water Resources Development Act of 1986 authorized funding for a long list of new water projects, but at the same time it increased local cost share formulas. For large navigation projects and structural flood control projects, local entities saw their portion of the costs rise from nothing to as much as half. Because the new formulas were announced after the legislators' initial requests for project funding, the economists were able to measure how legislators revised the scale of the project when local costs increased.

"The share of projects that disappeared completely was high," notes Del Rossi. Price elasticities were also high. For every 1 percent increase in cost that the locals had to pay, the dollar size of requests fell by 1.27 percent for flood control projects and 2.55 percent for large navigation projects. The overall project costs for the 82 projects in the study sample dropped by 35 percent, and the federal share fell by 48 percent.

"So there was a big change in the requested project, (and its) final size, when the locals had to pay more," said Del Rossi. "It showed that in the past, these things have been inefficiently too big. It's a common economic issue. If you don't fully take into account the costs of your actions, you're not going to make the right choice from the efficiency perspective, you're going to do too much of something. In this case, build too big a project."

Greasing the wheels of change

While improved efficiency in government expenditure is a desirable goal, it's clear that efficiency is not the only criterion for judging whether or not pork is bad. Spending centrally collected taxpayer dollars on local projects may serve a redistributive function, allocating federal funds to poorer areas. Indeed, a quick look at the state-by-state relationship between per capita pork levels and poverty shows a moderate correlation if outliers like Alaska and Hawaii are excluded from the calculation.

Unfortunately, if income redistribution is the policy goal, earmarks are a bad delivery mechanism. Earmarks themselves tend not to focus specifically on programs or projects for poor people. Rather, they tend to be concentrated in policy areas where congressional members have leverage on appropriations committees (see "This little piggy came home").

A more widely acknowledged rationale for earmarks is the inescapable and important function of them in the political economy of representative democracies. In short, a little pork, regardless how fatty, helps get more important legislative matters through Congress.

Economists revere efficiency and might be expected to disagree with the notion and insist that earmarking be stopped entirely. But most who have studied it believe earmarking is inherent in political institutions. According to Weingast and Shepsle, pork in its various forms "will always serve as part of the legislator's response to his voters' retrospective question, 'What have you done for me lately?'" As a result, they add, "economic inefficiency will likely be a permanent characteristic of the distributive policies of legislative institutions."

V. V. Chari, a University of Minnesota economist and visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, agreed. "Pork barrel spending or earmarks may well be inevitable in a democratic system where both the legislature and the executive have partial authority on spending decisions," Chari said in an interview. Chari and Harold Cole wrote a 1995 Minneapolis Fed staff paper that concluded that institutional constraints like majority voting rules meant that "representative democracies are prone to pork barrel spending."

The reason for this is fairly straightforward. Congressional representatives tend to focus on getting re-elected by serving the specific needs of their constituents. They have relatively little incentive to work on bills that serve the general interest because they can free ride on the efforts of others. Political economists call this a collective action problem: Public goods (including general interest legislation) may be produced at inefficiently low levels because members of the group will tend to free ride on the contributions of others. A solution to this problem: pork. That is, if congressional leaders, or the president, reward members of Congress through earmarked expenditure, they can gain their support for passage of general interest legislation.

John Ellwood is a professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, and has written about the virtues of earmarks. "Pork barrel spending can be a good thing if it's used to buy votes for doing something for the greater good," said Ellwood in an interview. "Given the size of government, these are relatively cheap, and a good leader can use them as payments to buy votes or put together a coalition for doing the big important things."

Diana Evans, a political scientist at Trinity College, argues that this approach underlies much of the way Congress works today. "Pork barrel benefits are used strategically by policy coalition leaders to build the majority coalitions necessary to pass broad-based, general interest legislation," she writes in her prize-winning 2004 book, Greasing the Wheels. "Leaders do so by tacking a set of targeted district benefits onto such bills, using the benefits as a sort of currency to purchase legislators' votes for the leaders' policy preferences."

Evans shows that major pieces of controversial legislation, including the North American Free Trade Agreement and the tax reforms of 1986, were passed due in part to the skillful bargaining of political leaders who traded pork projects for legislative support. "The irony of this coalition-building strategy is that pork barrel legislation, the most reviled of Congress's legislative products, is used to produce the type of policy that is most admired: general interest legislation."

The point of pork, as one article noted, is to "help sweeten an otherwise unpalatable piece of legislation," because its costs are far outweighed by the benefits derived from passage of other important legislation. For example: The pork costs necessary to pass the 1986 Tax Reform Act—estimated by Wall Street Journal reporters Jeffrey Birnbaum and Alan Murray at $11 billion—were small relative to the benefits reaped from closing hundreds of billions of dollars' worth of permanent tax loopholes. "Even the most committed congressional reformers realized," Birnbaum and Murray wrote in their book Showdown at Gucci Gulch, "that these relatively small provisions were a necessary price to pay."

Sweet or sour pork?

While it's not hard to imagine how landmark legislation generates more earmarks, the steady and steep upward trend of earmark spending suggests that the past decade and a half has been witness to the halcyon days of landmark lawmaking. An alternative explanation: Congress decided it need not save such vote-getting measures for just the big stuff.

Indeed, also ignored in this argument is why earmarking has skyrocketed of late while the number of congressional members who need cajoling has not changed since the late 1950s, when senators from Alaska and Hawaii were added upon statehood. (Member- ship in the House of Representatives has stood at 435 for close to a century and was officially frozen into law about 80 years ago.)

If earmarking is a natural and necessary part of the political process, a stasis in congressional membership by itself should produce some sort of long-term pattern or equilibrium level for earmarks, whether measured by number or total spending, as a percentage of discretionary or total spending or even by major legislation, whatever its definition. No such historic patterns are obvious, and such incongruence suggests that either the relative value of pork has deflated (and thus more of it is needed to obtain votes) or the pattern of pork spending is unnecessarily large and therefore wasteful to some unknown degree.

The earmarks-for-votes rationale also implies that all approved laws—particularly those for which earmarks have influenced voting—are virtuous. Overlooked is the very real opportunity for the inverse: Pork is used to get lawmakers to look the other way on questionable legislation that otherwise has no chance of passage. It's impossible to say whether or how frequently this might happen. But the tax code, with its innumerable carve-outs and loopholes, offers some circumstantial evidence of such legislative horse trading.

Leaner, more visible cuts of pork?

While economists and others might seek an outright ban on earmarks, that's neither a political reality nor necessarily even a desirable goal. Some pork, it seems, is the grease that keeps the wheels of Congress rolling. Whatever the flaws of earmarks, there are no easy solutions. If earmarks were outlawed, it's entirely possible that an equivalent system of patronage would simply reappear on the inside of appropriation bills, rather than tagged alongside such legislation; without earmarks, the federal government might also produce an inefficiently low level of public goods.

But neither should the current earmark trends be shrugged off. "Are there things that we can do within the framework of representative democracy that would minimize the inefficiencies (of earmarks)?" asked Chari, the University of Minnesota economist, rhetorically. "The answer is yes."

For one, institutional rules might be improved. One such mechanism is to establish independent commissions to study spending projects and make recommendations to decision-making authorities that are required to vote for or against the entire list of recommendations. "An up-or-down vote," Chari said. "Congress could delegate these kinds of decisions to independent bodies and accept or reject their recommendations."

But if earmarks are merely a byproduct of the lawmaking process, rather than its intended outcome, then the vote of an independent body might also have unseen effects on the political process itself. Of course, or those critical of the current political process, that might be a risk well worth taking.

A second device would be to better differentiate between local and national spending responsibilities. "Congress could stop a lot of these problems if it would stop treating what are in many cases local public goods as global public goods," said Chari. Abolishing the federal government's responsibility for funding the national highway system might make sense, he said, since states could raise their own gas taxes to provide for their own transportation systems. "It might not be perfect," he admitted, "but the broader issue is [for the federal government] to get out of trying to provide what are local public goods and are more properly the domain of state and local governments."

Two practical measures were suggested by Del Rossi, from St. Lawrence University: Require an economic feasibility test or cost-benefit analysis for each earmark proposal and increase local cost sharing. The first measure might provide a "minimum level" of net social benefits from earmark projects and constrain legislators from funding projects "that are much too large." Increasing local cost sharing would force legislators to internalize more costs and move project sizes closer to socially efficient levels. "You can control spending better if you make the people who are going to benefit consider the costs," she noted.

One final tactic takes comparatively little effort and could have a significant effect: transparency. Until recently, the source or sponsor of individual earmarks was conveniently omitted from appropriations bills and, by extension, from public scrutiny. After hitting its zenith of almost $30 billion in 2006, public outrage sparked calls in both houses for more earmark transparency.

The effect has been fairly dramatic, at least so far. In 2007, only two of the 11 appropriations bills enacted by Congress had earmarks. The remaining appropriations bills were subject to a moratorium that Congress placed on itself that year, according to CAGW. As a result, the number and total spending of earmarks plummeted significantly, both nationwide and in district states.

It took literally all of 2007, but Congress managed to pass all appropriations bills for fiscal year 2008, and for the first time also required that earmark sponsors be identified. The final tally for fiscal year 2008 earmarks showed a large bounce in the number of earmarks compared to the preceding year, as well as a slight increase in the amount of earmark spending. But both the number and cost of earmarks are well down from their peak levels.

Red meat

In a quotation often attributed to Otto von Bismarck, it's said that sausage-making and lawmaking are two processes we really shouldn't watch. It isn't surprising that pork is part of both. But while it is easy to criticize earmarking as a wasteful and inefficient use of taxpayer dollars, it's hard for all parties to agree on what should be eliminated. Indeed, that's part of the reason earmarking persists.

As former Fed governor Edward Gramlich once observed, "One guy's pork is another guy's red meat." So while the dynamics of earmarking generate predictable inefficiencies, the political economy of pork suggests that it is an inevitable and, at times, possibly beneficial part of a representative democracy.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.